Science and technology in Kyrgyzstan

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Science and technology in Kyrgyzstan examines government efforts to develop a national innovation system and the impact of these policies.

Socio-economic context

[edit]

Most of the Central Asian economies have emerged relatively unscathed from the global financial crisis of 2008–2009. Kyrgyzstan's performance has been more erratic, but this trend was visible well before 2008. The Kyrgyz economy was shaken by a series of shocks between 2010 and 2012. In April 2010, President Kurmanbek Bakiyev was deposed by a popular uprising, with former minister of foreign affairs Roza Otunbayeva assuring the interim presidency until the election of Almazbek Atambayev in November 2011. Food prices rose two years in a row and, in 2012, production at the major Kumtor gold mine fell by 60% after the site was perturbed by geological movements. According to the World Bank, 33.7% of the population was living in absolute poverty in 2010 and 36.8% a year later.[1]

In 2012, Kyrgyzstan's external debt (89%) was higher than that of its neighbors, after dropping to 71% in 2009. Turkmenistan had reduced its external debt to just 1.6% of GDP (down from 35% in 2002) and Uzbekistan's external debt was just 18.5% of GDP. Kazakhstan's external debt remained relatively stable at 66%, whereas Tajikistan's external debt had climbed to 51% (from 36% in 2008).[2]

Although both exports and imports have grown impressively over the past decade, the five Central Asian republics remain vulnerable to economic shocks, owing to their reliance on exports of raw materials, a restricted circle of trading partners and a negligible manufacturing capacity. Kyrgyzstan has the added disadvantage of being considered resource-poor, although it does have gold reserves and ample water. Most of its electricity is generated by hydropower.[1]

Like the other four Central Asian republics, Kyrgyzstan is implementing structural reforms to improve competitiveness, as it gradually moves from a state-controlled economy to a market economy. In particular, the government has been striving to modernize the industrial sector and foster the development of service industries to reduce the share of agriculture in GDP. Between 2005 and 2013, the share of agriculture in the Kyrgyz economy dropped from 6.8% to 4.9% of GDP and the services sector expanded from 53.1% to 58.2% of GDP but the share of industry receded from 40.1% to 37.8% of GDP.[1]

Kyrgyzstan has the second-lowest GDP per capita in Central Asia after Tajikistan. GDP per capita rose from $2,449 to $3,213 (in purchasing power parity dollars) between 2009 and 2013. This compares with $23,214 in Kazakhstan, the Central Asian republic with the highest GDP per capita. Kyrgyzstan ranked 125th in the Human Development Index in 2013. The same year, the Earth Institute made an effort to measure the extent of happiness in 156 countries. Kazakhs (57th), Turkmens (59th) and Uzbeks (60th) were found to be happier than the Kyrgyz (89th) and, above all, the Tajiks (125th).[1]

Internet access varies widely from one country to another. In 2013, just one in four (23%) Kyrgyz had access to internet, compared to 54% of the population in Kazakhstan and 38% in Uzbekistan, the most populated Central Asian republic. This compares with 16% in Tajikistan and 10% in Turkmenistan.[1]

By 2017, Kyrgyzstan hopes to figure in the Top 30 of the World Bank's Doing Business ranking and no lower than 40th in the global ranking for economic freedom or 60th for global enabling trade. By combining a systematic fight against corruption with legal regulation of the informal economy, Kyrgyzstan hopes to figure among the Top 50 least corrupt countries in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index by 2017.[1]

Higher education

[edit]Kyrgyzstan spends more on education than most of its neighbors : 5.53% of GDP in 2014, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics.[3] This is close to the level in 2008 (5.91% of GDP) but lower than the peak in government education spending of 7.40% of GDP in 2012. Higher education spending has declined in recent years from 0.97% of GDP in 2008 and 0.89% of GDP in 2012 to just 0.26% of GDP in 2014.[1]

According to the government's Review of the Cost-Effectiveness of the Education System of Kyrgyzstan, there were 52 institutions offering higher education in 2011. Many universities are more interested in chasing revenue than providing quality education; they multiply the so-called ‘contract’ student groups who are admitted not on merit but rather for their ability to afford tuition fees, thereby saturating the labor market with skills it does not want. The professionalism of faculty is also low. In 2011, six out of ten faculty held only a bachelor's degree, 15% a master's, 20% a Candidate of Science degree, 1% a PhD and 5% a Doctor of Science (the highest degree level).[1]

The National Education Development Strategy (2012−2020) prioritizes improving the quality of higher education. By 2020, the target is for all faculty to have a minimum master's qualification and for 40% to hold a Candidate of Science and 10% either a PhD or Doctor of Science degree. The quality assurance system is also to be revamped. In addition, the curriculum will be revised to align it with national priorities and strategies for the region's economic development. A teacher evaluation system will be introduced and there will be a review of existing funding mechanisms for higher education.[1]

Science and technology

[edit]

Kyrgyzstan was ranked 99th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024[4].

Policy issues, 2010–2015

[edit]The Kyrgyz economy is oriented primarily towards agricultural production, mineral extraction, textiles and the service industry. There is little incentive to create knowledge- and technology-based industries. The insufficient rate of capital accumulation also hampers structural changes designed to boost innovation and technology-intensive industries. Every key economic sector is technologically dependent on other countries. In the energy sector, for instance, all technological equipment is imported from abroad and many of its assets are in foreign hands.[1] In 2013 and 2014, three partly state-owned Russian companies invested in Kyrgyzstan's hydropower, oil and gas industries. In 2013, RusHydro began building the first of a series of hydroelectric dams that it will manage. In February 2014, Rosneft signed a framework agreement to buy 100% of Bishkek Oil and a 50% stake in the sole aviation fuel provider at the country's second-biggest airport, Osh International. The same year, Gazprom came closer to acquiring 100% of Kyrgyzgaz, which operates the country's natural gas network. In return for a symbolic investment of US$1, Gazprom undertook to assume US$40 million in debt and invest 20 billion rubles (circa US$551 million) in modernizing Kyrgyz gas pipelines between 2014 and 2019. Gazprom already provides most of the country's aviation fuel and has a 70% share in the retail gasoline market.[5]

Kyrgyzstan needs to invest heavily in priority sectors like energy to improve its competitiveness and drive socio-economic development. However, the low level of investment in research and development, both in terms of finance and human resources, is a major handicap. In the 1990s, Kyrgyzstan lost many of the scientists it had trained during the Soviet era. Brain drain remains an acute problem and, to compound matters, many of those who remain are approaching retirement age. Although the number of researchers has remained relatively stable over the past decade, research makes little impact and tends to have little application in the economy. Research is concentrated in the Academy of Sciences, suggesting that universities urgently need to recover their status as research bodies. Moreover, society does not consider science a crucial driver of economic development or a prestigious career choice.[1]

The government's National Strategy for Sustainable Development (2013−2017) recognizes the need to remove controls on industry in order to create jobs, increase exports and turn the country into a hub for finance, business, tourism and culture within Central Asia. With the exception of hazardous industries where government intervention is considered justified, restrictions on entrepreneurship and licensing will be lifted and the number of permits required will be halved. Inspections will be reduced to a minimum and the government will strive to interact more with the business community. The state reserves the right, however, to regulate matters relating to environmental protection and conservation of ecosystem services.[1]

In 2011, the government devoted just 10% of GDP to applied research, the bulk of funding going to experimental development (71%). The State Program for the Development of Intellectual Property and Innovation (2012−2016) sets out to foster advanced technologies, in order to modernize the economy. This program will be accompanied by measures to improve intellectual property protection and thereby enhance the country's reputation in relation to the rule of law. A system will be put in place to counter trafficking in counterfeit goods and efforts will be made to raise public awareness of the role and importance of intellectual property. During the first stage (2012−2013), specialists were trained in intellectual property rights and relevant laws were adopted. The government is also introducing measures to increase the number of bachelor's and master's degrees in science and engineering fields.[1]

Policy issues, 2015–2019

[edit]In 2015, Kyrgyzstan approved its Concept for Reform of the Organization of the Scientific System. This document proposed creating a regulatory framework to guide the training and certification of research personnel for easier integration into global scientific networks. The Law on Science and the Basics of State Scientific and Technical Policy followed in 2017 to provide this regulatory framework. The Concept for Reform also proposed a tripartite system of research funding: core funding for research infrastructure, administration and personnel; program-targeted funding, granted on a competitive basis to support research in accordance with government priorities; and research grants.[6]

Much of the government research budget still goes towards fixed costs such as salaries or, in other words, core funding. The Academy of Sciences consequently suffers from low levels of project funding. In 2019, it counted 1 810 employees and 53 ongoing research projects funded through the state budget (ca US$1.7 million) and international science foundations (ca US$1.04 million).[6]

The Academy of Sciences sets its own research priorities. For 2013–2017, these were:[6]

- water and energy, including renewables;

- information technology, mathematical modelling and

- management;

- materials (nanotechnology, biotechnology);

- geosciences and natural resources;

- mechanical and instrument engineering;

- reproduction of biological resources and biosecurity;

- ecology, human ecology and climate change; and

- the individual and society: challenges of globalization.

Research trends

[edit]Financial investment

[edit]

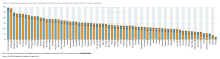

Investment in research and development is low in all five Central Asian republics. In Kyrgyzstan, it has hovered around the 0.2% of GDP mark since 2001. In 2011, the country devoted 0.16% of GDP to research.[1] By 2017, investment had dropped to 0.11% of GDP.[6]

Human resources

[edit]Kyrgyzstan counted 412 researchers per million inhabitants (in head counts) in 2011, less than one-third the global average (1,083 in 2013). The great majority of researchers are employed by the public sector: 53% work in the government sector and 34% in the higher education sector. Most researchers are working in the field of natural sciences (27%) and engineering (26%), followed by the health sector (18%).[1]

In 2018, Kyrgyzstan counted 563 researchers per million inhabitants (in head counts).[6]

Gender issues

[edit]Like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan has maintained a share of women researchers above 40% since the fall of

the Soviet Union. In 2011, 42% of Kyrgyz researchers were women. When broken down by field, women accounted for 47% of researchers in natural sciences, 30% of those in engineering, 44% of researchers in medical sciences, 50% of those in agriculture and 49% of those in social sciences and humanities. Among university graduates, women dominated natural sciences (61%) and health (77%) in 2013 but were in the minority in engineering (26%) and agriculture (28%). Of note is that the majority of PhDs in both science (63%) and engineering (54%) were awarded to women in 2012.[1]

Table: PhDs obtained in science and engineering in Central Asia, 2013 or closest year

| PhDs | PhDs in science | PhDs in engineering | ||||||||

| Total | Women (%) | Total | Women (% | Total per million population | Women PhDs per million population | Total | Women (% | Total per million population | Women PhDs per million population | |

| Kazakhstan (2013) | 247 | 51 | 73 | 60 | 4.4 | 2.7 | 37 | 38 | 2.3 | 0.9 |

| Kyrgyzstan (2012) | 499 | 63 | 91 | 63 | 16.6 | 10.4 | 54 | 63 | – | – |

| Tajikistan (2012) | 331 | 11 | 31 | – | 3.9 | – | 14 | – | – | – |

| Uzbekistan

(2011) |

838 | 42 | 152 | 30 | 5.4 | 1.6 | 118 | 27.0 | – | – |

Source: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (2015), Table 14.1

Note: PhD graduates in science cover life sciences, physical sciences, mathematics and statistics, and computing; PhDs in engineering also cover manufacturing and construction. For Central Asia, the generic term of PhD also encompasses Candidate of Science and Doctor of Science degrees. Data are unavailable for Turkmenistan.

Table: Central Asian researchers by field of science and gender, 2013 or closest year

| Total researchers (head counts) | Researchers by field of science (head counts) | |||||||||||||||

| Natural Sciences | Engineering and technology | Medical and health sciences | Agricultural sciences | Social sciences | Humanities | |||||||||||

| Total researchers | Per million pop. | Number of women | Women (% | Total | Women (% | Total | Women (%) | Total | Women (%) | Total | Women (%) | Total | Women (%) | Total | Women (%) | |

| Kazakhstan

2013 |

17 195 | 1 046 | 8 849 | 51.5 | 5 091 | 51.9 | 4 996 | 44.7 | 1 068 | 69.5 | 2 150 | 43.4 | 1 776 | 61.0 | 2 114 | 57.5 |

| Kyrgyzstan

2011 |

2 224 | 412 | 961 | 43.2 | 593 | 46.5 | 567 | 30.0 | 393 | 44.0 | 212 | 50.0 | 154 | 42.9 | 259 | 52.1 |

| Tajikistan

2013 |

2 152 | 262 | 728 | 33.8 | 509 | 30.3 | 206 | 18.0 | 374 | 67.6 | 472 | 23.5 | 335 | 25.7 | 256 | 34.0 |

| Uzbekistan

2011 |

30 890 | 1 097 | 12 639 | 40.9 | 6 910 | 35.3 | 4 982 | 30.1 | 3 659 | 53.6 | 1 872 | 24.8 | 6 817 | 41.2 | 6 650 | 52.0 |

Source: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (2015), Table 14.1

Research output

[edit]The three main partners of Kazakh scientists are based in the Russian Federation (99 co-authored articles between 2008 and 2014), Germany and Turkey (74 each), the USA (56) and Kazakhstan (43). Kyrgyz scientists publish most in geosciences but output remains low. According to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science, Kyrgyz scientists published 46 articles in internationally catalogued journals in 2005 and 82 in 2014. This amounts to 15 articles per million inhabitants in 2014. The global average in 2013 was 176 per million and the average for sub-Saharan Africa was 20 per million. Kazakhstan published 36 articles per million inhabitants in 2014.[1] Language may play a role in the low count in international journals, as the Thomson Reuters' database tends to favor articles written in English.

Between 2008 and 2013, no Kyrgyz, Tajik or Turkmen patents were registered at the US Patent and Trademark Office, compared to five for Kazakh inventors and three for Uzbek inventors.[1]

International co-operation

[edit]Like the other four Central Asian republics, Kyrgyzstan is a member of several international bodies, including the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Economic Cooperation Organization and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Kyrgyzstan and the other four republics are also members of the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Program, which also includes Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, China, Mongolia and Pakistan. In November 2011, the 10 member countries adopted the CAREC 2020 Strategy, a blueprint for furthering regional co-operation. Over the decade to 2020, US$50 billion is being invested in priority projects in transport, trade and energy to improve members’ competitiveness. The landlocked Central Asian republics are conscious of the need to co-operate in order to maintain and develop their transport networks and energy, communication and irrigation systems.[1]

Kyrgyzstan joined the Eurasian Economic Union in 2014, shortly after it was founded by Kazakhstan, Belarus and the Russian Federation. Armenia is also a member. As co-operation among the member states in science and technology is already considerable and well-codified in legal texts, the Eurasian Economic Union is expected to have a limited additional impact on co-operation among public laboratories or academia but it may encourage business ties and scientific mobility, since it includes provision for the free circulation of labor and unified patent regulations.[1][7]

Kyrgyzstan has been involved in a project launched by the European Union in September 2013, IncoNet CA. The aim of this project is to encourage Central Asian countries to participate in research projects within Horizon 2020, the European Union's eighth research and innovation funding program. The focus of this research projects is on three societal challenges considered as being of mutual interest to both the European Union and Central Asia, namely: climate change, energy and health. IncoNet CA builds on the experience of earlier projects which involved other regions, such as Eastern Europe, the South Caucasus and the Western Balkans. IncoNet CA focuses on twinning research facilities in Central Asia and Europe. It involves a consortium of partner institutions from Austria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Poland, Portugal, Tajikistan, Turkey and Uzbekistan. In May 2014, the European Union launched a 24-month call for project applications from twinned institutions – universities, companies and research institutes – for funding of up to €10,000 to enable them to visit one another's facilities to discuss project ideas or prepare joint events like workshops.[1]

The International Science and Technology Center (ISTC) was established in 1992 by the European Union, Japan, the Russian Federation and the US to engage weapons scientists in civilian research projects and to foster technology transfer. ISTC branches have been set up in the following countries party to the agreement: Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The headquarters of ISTC were moved to Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan in June 2014, three years after the Russian Federation announced its withdrawal from the center.[1]

Kyrgyzstan has been a member of the World Trade Organization since 1998.

Sources

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 365-377, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 365-377, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: the Race Against Time for Smarter Development, UNESCO, UNESCO publishing. To learn how to add open license text to Wikipedia articles, please see this how-to page. For information on reusing text from Wikipedia, please see the terms of use.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Mukhitdinova, Nasiba (2015). Central Asia. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 365–387. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ^ "Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (SESRIC) database". Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. 2014.

- ^ "Database on government expenditure on higher education as a percentage of GDP". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 6 June 2017.

- ^ World Intellectual Property Organization (2024). Global Innovation Index 2024. Unlocking the Promise of Social Entrepreneurship. Geneva. p. 18. doi:10.34667/tind.50062. ISBN 978-92-805-3681-2. Retrieved 2024-10-22.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Satke, Ryseldi (27 March 2014). "Russia tightens hold on Kyrgyzstan". Nikkei Asia Review. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Eröcal, D. and I. Yegorov (2021) Countries in the Black Sea Basin. In UNESCO Science Report: the Race Against Time for Smarter Development. Schneegans, S.; Straza, T. and J. Lewis (eds). UNESCO Publishing: Paris

- ^ Erocal, Deniz; Yegorov, Igor (2015). Countries in the Black Sea basin. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 324–341. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.