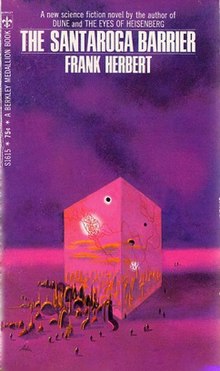

The Santaroga Barrier

Cover of first edition (paperback) | |

| Author | Frank Herbert |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Paul Lehr[1] |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Berkley Books |

Publication date | 1968 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 255 |

| ISBN | 0-7653-4251-0 |

The Santaroga Barrier is a 1968 science fiction novel by American writer Frank Herbert. Considered to be an "alternative society" or "alternative culture" novel,[2] it deals with themes such as psychology, the counterculture of the 1960s, and psychedelic drugs.[3] It was originally serialized in Amazing Stories magazine from October 1967 to February 1968, and came out in a paperback from Berkley Books later in 1968.[4] The book has been described as "an ambiguous utopia,"[5][6] and Herbert told Tim O'Reilly that The Santaroga Barrier was intended to describe a society that "half my readers would think was utopia, the other half would think was dystopia."[5] O'Reilly writes:

In deliberate imitation of [B.F.] Skinner's Walden Two, the story is organized around a "conversion" theme, in which a hostile outsider is persuaded of the merits of a society he initially criticizes. Where Skinner makes a sincere attempt to sell a utopian ideal, however, Herbert's deeper concern is to re-create the process by which a man gives up his individual perspective for a group dream.[7]

Plot summary

[edit]A psychologist, Gilbert Dasein, is hired by corporate interests to investigate Santaroga, a southern California[8] town in a valley where marketing seems totally ineffective: outside businesses are allowed in, but wither quickly for lack of business. Santarogans aren't hostile toward the enterprises, they just won't shop there. Nor are they xenophobic; they instead appear maddeningly self-satisfied with their quaint, local lifestyle. Adding an element of danger, the last few psychologists sent in have all died in accidents that are (seemingly) perfectly plausible. Complicating matters further still, the psychologist's college girlfriend, Jenny, has returned to Santaroga, her hometown.

With this in mind, Dasein cautiously enters the town and quickly learns of 'Jaspers', an additive in the food and drink commonly ingested in Santaroga that seems to imbue the consumer with greater health and an expanded mind. Within the Santarogan community, Jaspers was described as "Consciousness Fuel" which opened a person's eyes and ears, and turned on their minds.[9] Those who consume it don't become psychic; instead, they're simply far more lucid than the average citizen of the U.S., although there are numerous hints at a group mind operating at a subconscious level.[3] Their newspapers are vaguely subversive with their folksy, enlightened commentary on world affairs; their dinner conversations knowledgeably reference great theories of psychology, politics, and cognitive science.

Soon, Dasein is having narrow misses with perfectly plausible[10] accidents: a clerk adjusting valves in the kitchen floods Dasein's hotel room with gas;[11] Dasein trips on some loose carpeting, stumbles, falls through a stairwell railing and would have plunged three floors but was caught and saved by a Santarogan[12] (although the incident with the carpeting and fall through the stairwell railing appeared to be a fluke accident, Dasein later realizes it could have been part of a carefully laid trap[13]); a boy playing with a bow and arrow releases it, grazing Dasein's neck; the lift under his car in a garage collapses; a waitress in a diner accidentally uses insecticide rather than sugar for his coffee. Knowing that Jaspers creates exceptionally perceptive, penetrating individual minds, Dasein realizes that he has offended a communal id that feels threatened by him. As Jenny tries to convince him to settle down with her there, he wonders whether he'll live long enough to decide.

Allusions and references

[edit]The novel was loosely based on the ideas of the philosopher Martin Heidegger, noticeably on his book Being and Time (1927).[10]

The main character's name is Gilbert Dasein. Dasein is one of Heidegger's terms which roughly translates to 'being'.[3] It has also been suggested that the name may be a twist on 'Gilbert Gosseyn', a character in The World of Null-A (1948) by A. E. van Vogt.[citation needed] Jenny Sorge's surname refers to Heidegger's term Sorge, Heidegger's term for "caring", which Heidegger regarded as the fundamental concept of Intentionality.[5] The character Dr. Piaget was named for the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget.[3]

Jaspers, the psychoactive substance in the book, is named for Karl Jaspers, a German psychiatrist and philosopher and contemporary of Heidegger who claimed that individual authenticity required a joining with the "transcendent other," traditionally known as God.[3]

Reception

[edit]The science fiction author David Pringle rated The Santaroga Barrier three stars out of four and described the novel as "one of Herbert's more effective treatments of the hive mentality - and the possible next step in the evolution of human intelligence."[14]

References

[edit]- ^ isfdb

- ^ Malmgren, Carl Darryl (1991) Worlds apart: narratology of science fiction Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, page 79, ISBN 0-253-33645-7

- ^ a b c d e Gary K. Wolfe, (1979).

- ^ Herbert, Frank (1968) The Santaroga Barrier (A Berkley medallion book, S1615) Berkley Publishing Corporation, New York OCLC 18111876

- ^ a b c O'Reilly, Timothy. Frank Herbert, Ungar, 1981, ISBN 080442666X (p.131-33).

- ^ Frank Herbert by Timothy O'Reilly. Google books. Retrieved 01 June 2014

- ^ "Tim O'Reilly - Frank Herbert: Chapter 6: An Ecology of Consciousness - O'Reilly Media". www.oreilly.com. Retrieved 2023-04-07.

- ^ Herbert 1982, p. 23: The book never states "southern California" but describes the location of Santaroga as "Porterville was 25 miles away, ten miles outside the valley on the road he had taken. The other direction led over a winding, twisting mountain road some forty miles before connecting with highway 395."

- ^ Herbert 1982, p. 106.

- ^ a b Herbert, Brian (2003) Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert Tor, New York, pages 216-217, ISBN 0-7653-0646-8

- ^ Herbert 1982, pp. 26–29.

- ^ Herbert 1982, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Herbert 1982, p. 76.

- ^ David Pringle,The Ultimate Guide To Science Fiction.New York: Pharos Books: St.Martins Press, 1990.ISBN 0886875374 (p.269).

In spite of the reference to towns and highways, the presence of a forested landscape including redwood trees imply northern California as the setting.

Sources

[edit]- Herbert, Frank (July 1982). The Santaroga Barrier. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 0-425-05944-8.

- Wolfe, G.K. "Santaroga Barrier, The – Frank Herbert", in Magill, Frank Northern (editor) (1979) Survey of Science Fiction Literature Salem Press, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, pp. 1859–1862, ISBN 0-89356-194-0

External links

[edit]- The Santaroga Barrier title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database