Santa Maria del Canneto (Pula, Croatia)

The Basilica of Santa Maria del Canneto, or Santa Maria Formosa, was a sixth-century Byzantine church erected in Pola (modern-day Pula, Croatia) under the patronage of Maximianus, bishop of Ravenna. The structure was damaged at the time of the Venetian sack of Pola in 1243, and building material was subsequently taken from the ruins and primarily incorporated into the Marciana Library and the Basilica of Saint Mark in Venice. Of the large, triple-nave church, comparable in splendour to the Euphrasian Basilica in Parenzo (modern-day Poreč),[1] only one of the lateral chapels survives. It constitutes the sole construction in Pola dating to the Byzantine period.[2]

History of the basilica

[edit]

Edification

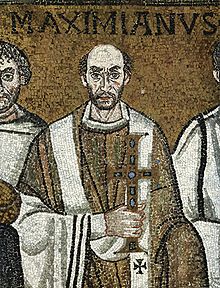

[edit]Installed as bishop of Ravenna in 546, Maximianus, a native of Vistar (Veštar) near Pola in Istria, continued the building programme of his predecessors Ecclesius and Ursicinus, completing the Basilicas of San Vitale and Sant'Apollinare in Classe. In Pola, where he had served as a young deacon, he had a new basilica erected on the site of a former temple of Minerva.[3][4] Andreas Agnellus, the historian of the Ravennate bishops, indicates in Liber Pontificalis Ecclesiae Ravennatis that the church in Pola was the first to be erected by Maximianus.[5] It was formally dedicated to the Virgin Mary under the title of Santa Maria Formosa. But since it was built in a low-lying area of the city near the marshes along the waterfront, it has been customarily known since the twelfth century as Santa Maria del Canneto (Saint Mary of the reeds).[6] From at least the eighth century, a Benedictine abbey was attached.[7] The abbey had jurisdiction over the Monastery of Saint Andrew di Serra, located on an island in the harbour of Pola.[8]

The church, 32 metres (105 ft) long and 19 metres (62 ft) wide, had three naves, divided by two rows of ten columns each that were surmounted by 'basket' capitals.[1] The columns sat on low-lying walls that separated the three naves, as originally in the Euphrasian Basilica.[9][10] Like other churches built in Africa and Italy following the Byzantine reconquest under Justinian, the floor of Santa Maria del Canneto was covered with mosaics.[11] On the basis of surviving fragments, these mosaics, predominantly green and red, depicted intertwined lilies and lotus flowers together with curvilinear patterns.[12] The central nave terminated in an apse with choir stalls for the monks and the cathedra of the abbot. In the centre rose the ciborium. The lateral naves ended in the prothesis, for the liturgical preparation of the bread and wine, and the diaconicon, for the dressing of the clergy. Attached to the structure, but independent, were two chapel-mausoleums, dedicated to Saint Andrew and to the Virgin Mary.[1][4]

Destruction

[edit]In the early ninth century, the Venetians began to exact tribute from the Istrian cities in the form of olive oil, wine, and boats. From Pola, in particular, there was a tribute of hemp and an armed galley to assist in patrolling the upper Adriatic. This tribute was confirmed in a series of treaties (802–813) and militarily enforced by Venice whenever the Istrian cities attempted to rebel or other cities, commercial rivals of Venice, sought to gain influence.[13] Rebellions in Pola were put down in 1145, 1150, and 1160, and in 1193 Venice intervened to drive the rival Pisans from the city. Pola was taken by the Venetians in 1228 and again in 1243. Finally, in 1331, the city gave itself to Venice.[14] But as a Venetian subject city, it was repeatedly raided by the Genoese and briefly occupied as part of the wars between Venice and Genoa.[15]

The progressive destruction of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Canneto seems to have begun when Pola was plundered at the time of the Venetian conquest of 1243 under the leadership of Giacomo Tiepolo and Leonardo Quirini.[1][16][17] The last abbot is recorded in 1258, after which the abbey passed in commendam to the Church of Saint Mark in Venice. A priest was henceforth nominated from Venice.[18] The maintenance of the church fell to the procurators of Saint Mark de supra, the Venetian magistrates responsible for the Church of Saint Mark and for the public buildings around Saint Mark's Square.

Despoliation

[edit]The basilica was stripped over time of its precious marbles and columns for use as building materials elsewhere. Some art historians maintain that these materials included the four carved alabaster columns that form the ciborium over the high altar in Saint Mark's Basilica.[19][20] The tradition narrates that they were taken from Santa Maria del Canneto during the reign of Doge Jacopo Tiepolo (1229–1249).[21]

Concerns for the precarious conditions of the basilica were expressed in 1545 when Nicolò Bernardo, procurator of Saint Mark de supra, instructed the Venetian representative in Pola to nominate surveyors who were to evaluate the nature and the cost of the work that would be needed to consolidate the structure and prevent it from falling into total ruin.[22] No record survives of the report, but workmen and supplies were sent from Venice in 1549. That same year, however, the procurators of Saint Mark de supra sent Jacopo Sansovino, their proto (consultant architect and buildings manager), with the precise task of selecting other building materials that could be removed and utilized to further embellish the Church of Saint Mark and to adorn the staircase of the Marciana Library in Venice.[23][24] Of particular interest were the marble columns in the nave which were to be substituted with brick supports. The Venetian architect Tommaso Temanza attests in Vite dei più celebri architetti e scrittori veneziani (1778) that Sansovino took columns and marbles from Santa Maria del Canneto in 1550 and 1551 for Saint Mark's Basilica and the Doge's Palace.[25] The despoliation is also confirmed in a petition by the citizenry of Pola to the procurators of Saint Mark, dated 1550, in which they request exoneration from the obligation to pay a tribute of one-tenth of the local olive oil production, citing the removal of columns, marbles, porphyry, and serpentinite.[26] The amount of salvaged building materials must have been considerable, given that three ships had to be hired to transport the 22 columns removed, along with the marbles.[27]

Surviving chapel

[edit]As late as the mid-nineteenth century, the apse, the prothesis and the diaconicon, the bases of the columns, and a portion of the perimeter wall of the original basilica were still reasonably intact as was one of the adjoining lateral chapels.[28] But little remains today with the exception of a reduced section of the perimeter wall, parts of the prothesis and the diaconicon, and the chapel. Given its form and relationship to the principal basilica, as well as the similarities with the fifth-century Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, it is believed that this chapel was probably built as a tomb: a seventeenth-century description records the presence of the sarcophagus of a bishop.[29]

The chapel, constructed in rough stone with brick vaults, is in the form of a Latin cross with an apse that is polygonal on the exterior and semi-circular within.[4] Its principal façade has been modified over time, only the arch above the central window being original to the early structure. But the remaining exterior walls are preserved. These are ornamented with blind arches and pilasters on the corners, unlike the exterior walls of most of the contemporary churches in Ravenna which are plain.[30][31] The interior of the chapel is lit by wide-arched windows in the central tower and small windows in the transepts and the nave. Three of these windows have their original pierced stone screens.[6]

Inside the chapel, the conch of the apse was originally covered with a golden mosaic which, as with many early depictions, showed Jesus as a beardless youth. The scene may have depicted the traditio legis. The subject, common in Paleochristian art, concerns the transmission of the gospel message and typically shows Christ, holding a scroll, with Saint Peter and Saint Paul on either side. At Santa Maria del Canneto, the heads of Christ and one of the two saints survive in a fragment now located in the nearby archaeological museum.[32] Alternatively, the scene may have been a traditio clavium, showing Christ giving the keys to Saint Peter. This would be more appropriate for a funerary chapel and would not be incompatible with the compresence of Saint Paul receiving the law.[6][33] Below the conch was a border in stucco with a repeat design of paired birds holding garlands of flowers and fruit. Of this, fragments survive. The frieze below the border contained the apostles and John the Baptist within illusionistic niches.[34]

While the mosaics in the older churches in Ravenna, which date to the Ostrogothic Kingdom, show a strong Western influence, the mosaics in Santa Maria del Canneto are stylistically closer to contemporary mosaics in Constantinople and demonstrate the greater ties to the East and the resulting artistic influence that characterized the period of Byzantine rule.[35] Significantly, the inscriptions in the mural mosaics of the main basilica were in Greek, unlike the churches in Ravenna where the inscriptions were in Latin.[11] This is consistent with the tradition that the mosaicists who worked at Santa Maria del Canneto actually came from Constantinople.[35]

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b c d Caprin, L'Istria nobilissima, p. 50

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., p. 21

- ^ Luciani, 'Pola', pp. 20 and 22

- ^ a b c Mackie, Early Christian Chapels..., p. 47

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., p. 12

- ^ a b c Mackie, Early Christian Chapels..., p. 48

- ^ The abbey may have been founded by Maximianus at the time of the construction of the basilica. But the earliest recorded abbot, Theodosius, was installed in 717. See Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria del Canneto..., pp. 12 and 22, note 6, and Kandler, 'Della Basilica di S. Maria Formosa in Pola', p. 172

- ^ Kandler, 'Della Basilica di S. Maria Formosa in Pola', p. 172 (see footnote)

- ^ Kandler, 'Della Basilica di S. Maria Formosa in Pola', pp. 173–174

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., p. 14

- ^ a b Tavano, 'Mosaici parietali in Istria', p. 248

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., pp. 14–15

- ^ Luciani, 'Pola', pp. 29 and 31

- ^ Luciani, 'Pola', pp. 31–32

- ^ Luciani, 'Pola', p. 32

- ^ Kandler, 'Della Basilica di S. Maria Formosa in Pola', p. 173

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., pp. 12–13

- ^ Caprin, L'Istria nobilissima, p. 51 note 1

- ^ Caprin, L'Istria nobilissima, p. 23

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., p. 13

- ^ Art historians do not unanimously agree on the origin or age of the columns. It has been alternatively suggested that they are Byzantine but come from lower Egypt, Syria, Asia Minor, Constantinople, or Ravenna and that they may even be thirteenth-century Venetian productions. See in general Weigel, Thomas, 'Le colonne del ciborio dell'altare maggiore di san Marco a Venezia: Nuovi argomenti a favore di una datazione in epoca protobizantina', Centro Tedesco di studi veneziani quaderni, 54 (2000), pp. 18–25.

- ^ Gallo, Jacopo Sansovino a Pola, p. 12

- ^ Gallo, Jacopo Sansovino a Pola, pp. 13–14

- ^ Giuseppe Carpin alternatively suggests that the columns used in the Marciana Library come from the arena in Pola. See Caprin, L'Istria nobilissima, p. 28

- ^ Temanza, Vite dei più celebri architetti..., vol. I, p. 244

- ^ Gallo, Jacopo Sansovino a Pola, p. 16

- ^ Gallo, Jacopo Sansovino a Pola, p. 14

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., p. 11

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., p. 20

- ^ Mackie, Early Christian Chapels in the West..., pp. 47–48

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., p. 16

- ^ Morassi, La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa..., p. 16

- ^ Sergio Tavano suggests that the scene may have more likely portrayed Christ acclaiming two apostles. See Tavano, 'Mosaici parietali in Istria', p. 249

- ^ Mackie, Early Christian Chapels in the West, p. 49

- ^ a b Tavano, 'Mosaici parietali in Istria', pp. 251–252

Bibliography

[edit]- Bovini, Giuseppe, Le antichità cristiane della fascia costiera istriana da Parenzo a Pola, 2 vols (Bologna: Patron, 1974)

- Caprin, Giuseppe, L'Istria nobilissima (Trieste: F. H. Schimpff, 1905)

- Gallo, Rodolfo, Jacopo Sansovino a Pola ([Venezia]: Comune di Venezia, 1926)

- Morassi, Antonio, 'La chiesa di Santa Maria Formosa o del Canneto in Pola', Bollettino d'arte del Ministero della pubblica istruzione: notizie dei musei, delle gallerie e dei monumenti d'Italia, 1924, n.1 (luglio 1924), 11-25

- Kandler, Pietro, 'Della Basilica di S. Maria Formosa in Pola', in Municipio di Pola, ed., Notizie storiche di Pola (Parenzo: Gaetano Coana, 1876), pp. 171–177

- Luciani, Tomaso, 'Pola', in Municipio di Pola, ed., Notizie storiche di Pola (Parenzo: Gaetano Coana, 1876), pp. 9–34

- Mackie, Gillian, Early Christian Chapels in the West: Decoration, Function and Patronage (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003)

- Tavano, Sergio, 'Mosaici parietali in Istria', Antichita altoadriatiche, N. 8 (1975), 245–273

- Temanza, Tommaso, Vite dei più celebri architetti, e scultori veneziani che fiorirono nel secolo decimosesto, 2 vols (Venezia: C. Palese, 1778)