San Francisco Police Department

| San Francisco Police Department | |

|---|---|

Patch | |

Vehicle door decal | |

Badge | |

Commemorative decal | |

| Abbreviation | SFPD |

| Motto | Oro en paz, fierro en guerra Gold in peace, iron in war |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | August 13, 1849 |

| Employees | 2,913 (2020) |

| Annual budget | $696 million (2020)[1] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| |

| Jurisdiction of the San Francisco Police Department, | |

| Population | 883,305 (2018) |

| Legal jurisdiction | As per operations jurisdiction |

| Governing body | San Francisco Police Commission |

| Operational structure | |

| Overseen by Board | San Francisco Police Commission |

| Headquarters | 1245 3rd Street San Francisco, California 94158 |

| Officers | 2,140[2] |

| Patrol Specials | 28 |

| Commissioners responsible |

|

| Agency executive |

|

| Bureaus | 6

|

| Patrol Divisions | 2

|

| Facilities | |

| Stations | 10 |

| Airbases | 1 |

| Patrol cars | 338 |

| Boats | 5 |

| Planes | none |

| Dogs | 25+ |

| Website | |

| SFPD.org | |

The San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) is the municipal law enforcement agency of the City and County of San Francisco, as well as the San Francisco International Airport in San Mateo County. In 2000, the SFPD was the 11th largest police department in the United States.[3]

The SFPD (along with the San Francisco Fire Department and the San Francisco Sheriff's Department) serves an estimated population of 1.2 million, including the daytime-commuter population and thousands of other tourists and visitors.

The department's motto is the same as that of the city and county: Oro en paz, fierro en guerra, Spanish for Gold in peace, iron in war.

History

[edit]Early years

[edit]The SFPD began operations on August 13, 1849, during the California gold rush under the command of Captain Malachi Fallon. At the time, Chief Fallon had a force of one deputy captain, three sergeants and 30 officers.[4]

In 1851, Albert Bernard de Russailh wrote about the nascent San Francisco police force:

As for the police, I have only one thing to say. The police force is largely made up of ex-bandits, and naturally the members are interested above all in saving their old friends from punishment. Policemen here are quite as much to be feared as the robbers; if they know you have money, they will be the first to knock you on the head. You pay them well to watch over your house, and they set it on fire. In short, I think that all the people concerned with justice or the police are in league with the criminals. The city is in a hopeless chaos, and many years must pass before order can be established. In a country where so many races are mingled, a severe and inflexible justice is desirable, which would govern with an iron hand.[5]

On October 28, 1853, the Board of Aldermen passed Ordinance No. 466, which provided for the reorganization of the police department. Sections one and two provided as follows:

The People of the City of San Francisco do ordain as follows:

Sec. 1. The Police Department of the City of San Francisco, shall be composed of a day and night police, consisting of 56 men (including a Captain and assistant Captain), each to be recommended by at least ten tax-paying citizens.

Sec. 2. There shall be one Captain and one assistant Captain of Police, who shall be elected in joint convention of the Board of Aldermen and assistant Aldermen. The remainder of the force, viz., 54 men, shall be appointed as follows: By the Mayor, 2; by the City Marshal, 2; by the City Recorder, 2; and by the Aldermen and assistant Aldermen, 3 each.

In July 1856, the "Consolidation Act" went into effect. This act abolished the office of City Marshal and created in its stead the office of Chief of Police. The first Chief of Police elected in 1856 was James F. Curtis a former member of the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance.

The SFPD is one of the pioneering forces for modern law enforcement, beginning in the early 1900s.

1975 strike

[edit]In early August 1975, the SFPD went on strike over a pay dispute, violating a California law prohibiting police from striking.[6] The city quickly obtained a court order declaring the strike illegal and enjoining the SFPD back to work. The court messenger delivering the order was met with violence and the SFPD continued to strike.[6] Only managers and African-American officers remained on duty,[7] with 45 officers and three fire trucks responsible for a city population of 700,000.[8] Supervisor Dianne Feinstein pleaded Mayor Joseph Alioto to ask Governor Jerry Brown to call out the National Guard to patrol the streets but Alioto refused. When enraged civilians confronted SFPD officers at the picket lines, the officers arrested them.[6] Heavy drinking on the picket line became common. After striking SFPD officers started shooting out streetlights, the ACLU obtained a court order prohibiting strikers from carrying their service revolvers. Again, the SFPD ignored the court order.[6] On August 20, a bomb detonated at the Mayor's Presidio Terrace home with a sign reading "Don't Threaten Us" left on his lawn.[9] On August 21 Mayor Alioto advised the San Francisco Board of Supervisors that they should concede to the strikers' demands.[9] The Supervisors unanimously refused. Mayor Alioto immediately declared a state of emergency, assumed legislative powers, and granted the strikers' demands.[10] City Supervisors and residents sued but the court found that a contract obtained through an illegal strike is still legally enforceable.[10]

Recent times

[edit]In 1997, the San Francisco International Airport Police merged with SFPD, becoming the SFPD Airport Bureau.[11]

SFPD was one of the last large agencies in California to adopt semi-automatic pistols. Starting in the early 1990s, officers stopped being issued .38 Special 6-shot revolvers. Instead, they were issued the .40 S&W Beretta Model 96GT (G standing for decocker only and T standing for Trijicon night sights), a variant of the Beretta 92 semi-automatic pistol. More recently, SIG Sauer pistols have replaced Beretta 96GTs as the standard SFPD service weapon.

As of September 8, 2011, ground was broken for San Francisco's new Public Safety Building (PSB) in Mission Bay. A replacement facility for the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) Headquarters and Southern District Police Station, the PSB also contains a fire station to serve the burgeoning neighborhood.

In 2014, the San Francisco Police Academy graduated its first publicly reported transgender police officer, Mikayla Connell.[12]

A 2016 report by the Department of Justice concluded that there was significant racial bias in SFPD treatment of African Americans.[13]

A new study conducted by the California Policy Lab and researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, found that after the San Francisco Police Department doubled its foot patrols in late 2017, it resulted in a reduction by about 16% in larceny theft and 19% in assaults across the city and 10 police station districts.[14]

In August 2022, the SFPD was understaffed by 300 officers.[15]

As of April 2024, the SFPD was operating in a "reactive" mode (that is, reacting to 911 emergency calls)—meaning that it was no longer able to pursue violations of most traffic laws (especially infractions).[16] From 2016 to 2023, the annual number of traffic tickets issued by SFPD fell by 96 percent, from 129,597 to 5,080.[17] That month, a Walgreens pharmacy in Civic Center was "ransacked" for a lengthy period of time by at least seven people in front of a KPIX-TV television producer and other "stunned" bystanders.[18] SFPD officers did not respond to the scene until four hours later, by which time the store had closed and no one was present to make a report about the incident.[18]

Organization

[edit]The San Francisco Police Department is led by a Chief of Police who is appointed by the Mayor of San Francisco. The chief works with two assistant chiefs and five deputy chiefs directing the six bureaus: Administration, Airport, Chief of Staff, Field Operations, Professional Standards and Principled Policing and Special Operations, as well as the Municipal Transportation Authority, and the Public Utilities Commission. There are commanders appointed to assist the Deputy Chief with the day-to-day operation of the bureaus.

Bureaus

[edit]The department is divided into six bureaus[19] which are either led by an Assistant Chief or Deputy Chief.

| Bureau | Commander | Description | Divisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administration Bureau | Chief of Administration | The Administration Bureau provides a variety of services in the areas of budget management, information technology, legal research and counsel, personnel service, and logistical support. | The bureau has 6 divisions under it such as the Forensic Services and Training and Education. |

| Airport Bureau | Chief of Airport | The Airport Bureau provides law enforcement, traffic control, and security to the San Francisco International Airport. | N/A |

| Chief of Staff | Chief of Staff | The Office of the Chief of Staff is responsible for providing administrative support to the Chief of Police, while effectively managing Media Relations, Risk Management Office (Internal Affairs, Legal Division, Professional Standards, and EEO). | The Chief of Staff oversees 6 divisions including Risk Management Unit and Internal Affairs Division. |

| Field Operations Bureau | Chief of Field Operations | The Field Operations Bureau manages the Patrol Division and Investigations Bureau of the Police Department. | Patrol divisions are broken down into two divisions: Golden Gate Division and Metro Division which are each led by San Francisco Police Commanders. |

| Professional Standards and Principled Policing Bureau | Chief of Professional Standards and Principled Policing | The Professional Standards and Principled Policing Bureau was established in February 2016, to oversee the proposed use of force reforms, as well as to coordinate efforts of the Police Department with the United States Department of Justice Collaborative Reform Initiative. | N/A |

| Special Operations Bureau | Chief of Special Operations | The Special Operations Bureau supports the other units of the department by providing specialized expertise and equipment when needed. | Divisions under Special Operations includes Homeland Security Unit, Municipal Transportation, and Tactical Company which comprises the SWAT team, Bomb Squad, Honda Unit, Mounted Unit, Canine Unit, and the Hostage Negotiation Team |

Equipment

[edit]The standard issue side arms issued by the SFPD are the SIG Sauer P226 chambered in .40 S&W.[20] Officers also carry batons (straight wood/straight expandable), pepper spray, a portable radio and handcuffs, and certified officers are authorized to carry AR-15 platform rifles chambered in 5.56×45mm NATO on patrol.

Vehicles

[edit]

The SFPD has several types of vehicles in use, among them are Trek Bicycle Corporation bicycles, the Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptor, Chevrolet Tahoe, and more recently the 2013 Ford Taurus and 2013 Ford Explorer. Like most police agencies throughout California, SFPD patrol units are painted in black clearcoat with the roof, doors, and pillars painted white from the factory. The front doors of their motor vehicles bear a blue seven-pointed star with the letters "S.F.P.D." printed in gold. This decal is also printed on the trunk, either near the center of the decklid (on sedans) or near the right taillight (on SUVs). The car's 'shop number' (used to identify all vehicles operated by the city) is printed on the front doors below the A-pillars, on the trunk near the left rear taillight, and on the roof to help air units visually identify cars. On the rear side panels on both sides of the car is a sticker reading "EMERGENCY DIAL 911".

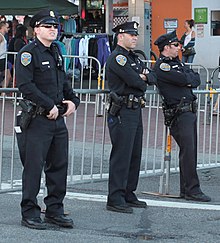

Uniform

[edit]

- The standard uniform is composed of a dark blue shirt and pants, with black braid, brass buttons which are stamped with the city seal and "SF POLICE." The black braid down the length of the pant increases in width as one advances up the ranks.

- Mounted police have a gold stripe going down the uniform pants

- Traffic Company have the "winged wheel" patch on the right sleeve of any long sleeve garment

- The Peaked cap of the officers has an 8-Point design unlike the "air force smooth cap" design of the LAPD or SFFD. The hat is adorned with a brass hat piece depicting the Arms of San Francisco.

- The uniform "badge" for Officers rank is a sterling silver seven-point star of a design basically unchanged since 1849. The terms "badge" or "shield" are not used by the department in any form. The "badge" worn by all officers of the department is referred to as a "star" and is recognized as such by the city and the department. Officers' stars are smooth polished metal, while those of Sergeants and above have decorative engraved designs. Those of Inspectors and above are 10k gold-filled badges instead of silver.

- The uniform originally had no patch, as with officers of the LAPD. It was not until 1969 that the patch, incorporating the San Francisco crest of arms, phoenix and city motto was added to the uniform in 1970, adorning both sleeves.

Rank structure

[edit]| Title | Insignia |

|---|---|

| Chief | |

| Assistant Chief | |

| Deputy Chief | |

| Commander | |

| Captain | |

| Lieutenant | |

| Inspector | |

| Sergeant | |

| Officer |

The SFPD has supplemental levels for ranks up to captain, depending on P.O.S.T. certification. Example; Q-2, Q-3 or Q-4 Police Officer for Basic, Intermediate and Advanced Peace Officer Standards and Training (P.O.S.T.) certification. Inspectors do not use chevrons to identify their rank—instead they wear a gold star badge similar to lieutenants and above. Sergeants and officers wear a silver star badge. Inspectors were initially the equivalent of a lieutenant rank and pay, but are now equivalent to a sergeant rank and pay. Tenured officers will have blue and gold hash-marks on the lower left sleeve of their Class A, B, and C (BDU) long-sleeved shirts. Each mark represents five years of service.

SFPD members are also eligible for bronze, silver, and gold Medals of Valor. Annually the nominees for these awards are reviewed by a board of police captains.[21] A Meritorious Conduct Award can also be awarded to department members.

San Francisco Police Reserve Officers

[edit]

The San Francisco Police Reserve Officer Unit is composed of individuals who wish to provide community service and give back to the city they live or work in. These officers understand the need for quality policing and community involvement, but cannot make the full commitment on becoming full-time peace officers.

A San Francisco Police Reserve Officer is a POST (Police Officer Standards and Training)-certified peace officer who volunteers his or her time. A Reserve Officer is classified as a Q-0 and has the same duties and authority as a full-time paid Police Officer while on duty. Officers patrol in vehicles, on bikes, on foot, and in some cases on marine craft. Reserve officers must meet the same stringent and comprehensive POST standards and training as regular full-time police officers. Most San Francisco Police Reserve Officers are Level 1 Reserve Officers, which is the highest level that is recognized by the State of California. The SFPD does accept Level 2 or Level 3 Reserve Officers, but based upon their respective levels which determine how a Reserve Officer is deployed.

Reserve Officers are responsible for serving a minimum of 24 volunteer hours per month to retain peace officers status, although there are Reserve Officers who routinely contribute two to three times that number.

Reserve Officers are involved in many areas of police work. Although most reserve officers actively participate in patrol, others work for such details as Muni, the Fugitive Recovery Enforcement Team, Vice, juvenile, emergency operations, DUI check-points, transporting prisoners, Command Van duty, and fixed posts at special events like 49er Football games and Sigmund Stern Grove performances.

Reserves are now organized like a company, with a complement of 40 Reserve Officers divided into three squads, each with a designated squad sergeant. For special events like New Year's Eve, Halloween night, and other citywide events, Reserves are assigned as a squad.

Before Reserve candidates are considered, they must meet the same eligibility criteria as a Q-2 Police Officer Recruit. Furthermore, each candidate must completed the required training prior to being appointed as a Reserve Police Officer. Once appointed, that officer must attend Continuing Professional Training, which is consistent with the requirements of regular full-time Officers every two years. There is also a 400-hour Field Training Program that Level 1 Reserves Officers must complete with a FTO officer. Reserve officers are held to the same performance standards as a full-time Police Officer and serve at the pleasure of the Chief of Police.[citation needed]

SWAT

[edit]

San Francisco has been known for their elite SWAT team, composed of volunteer and selected officers from the entire agency. Most training is done in-house, with occasional and required training by FBI instructors, other Federal Agencies and private Military instruction. The SWAT division participates in planned and coordinated raids with agencies such as the FBI, DEA, and the ATF. As of 2007, it is mandatory that SWAT team members are together, sometimes during routine patrol, and can be seen among the streets of San Francisco in BDU and traveling in a marked SUV, to ensure a quick and timely response to calls. They were under political fire in the highly publicized 1998 Western Addition Raid, in which more than 90 SFPD SWAT and Federal Agents raided a Western Addition housing project.[22] The SWAT team also executes high-risk warrants in the City and County of San Francisco. They are also one of the oldest serving agencies doing city crime suppression (the act of saturating high-crime areas with large numbers of officers and police presence—a more proactive approach) along with LAPD SWAT and NYPD Emergency Service Units.[23]

Housing Authority Police

[edit]The San Francisco Housing Authority Police was formed as an offshoot of the department in 1938 to patrol the various housing projects of the city.[24] In the 1990s they were completely absorbed back into the main Police Department.

C.R.U.S.H.

[edit]In the mid-1990s, San Francisco experienced the explosion of drug-related homicides,[25] which escalated to approximately 40 murders. Then-Chief Fred Lau sought the expertise of his veteran homicide Inspectors, Napoleon Hendrix (now deceased) and Prentice "Earl" Sanders (later Chief of Police), to put together a "top notch" task force, called CRime Unit to Stop Homicide, to solve and suppress the murders and investigate violent illegal narcotics cell groups and other violent crimes. Inspector Bob McMillan, Officer Nash Balinton and his partner Officer Paul Lozada,[26] Officer Mike Bolte, Officer Michael Philpott, and Sergeants John Monroe, Maurice Edwards and Kervin Silas, were personally selected to the unit by the Inspectors.

Motor Division

[edit]

The SFPD was one of the founding departments in the field of utilizing Police motorcycles (along with their counterparts across the bay in Berkeley). The unit was founded in 1909, and has grown ever since. They are officially under the command of the SFPD Traffic Division. They participate in many duties such as traffic enforcement, patrol, riot control, and special events and escorts. It is the only fully functional department that utilizes the entire traffic fleet for escorts in the nation. No other metropolitan city utilizes all its motor bikes for escorts but SFPD.

The entire 43-man unit is based at the Hall of Justice at 850 Bryant Street. Unlike most cities, they patrol as solo officers (hence the name SOLOS). They can frequently be seen throughout the city. The bulk of the unit is composed of Harley-Davidson Road King motorcycles. There is a separate division called Honda Unit, that is composed of Suzuki DR-Z400S dual-sport motorcycles (which is under the command of the Special Operations Bureau and not the same as Traffic), for city patrol and patrol in and around the area of Golden Gate Park. Otherwise, every one of the 10 main police stations in the city have 2 motorcycles under their command, used for patrol around their districts exclusively.

Aero Division

[edit]The SFPD "Aero" Squadron was at its peak in the mid-1970s, with the number of helicopter and small plane flights rivaling the frequency of the Los Angeles Police Department. After several accidents (one of which a helicopter crashed in Lake Merced, killing Officer Charles Logasa in 1971) and complaints about the "Eye in the Sky" program, the unit was disbanded. The helicopter unit was featured prominently in the first Dirty Harry film, identifying a sniper on a rooftop before a murder was committed. The unit was reactivated in the late 1990s, but after another fatal crash (which killed two SFPD officers, Kirk Bradley Brookbush and James Francis Dougherty) the Aero unit was put into an "inactive" status indefinitely.[27] In times where it needs air support, the SFPD contacts the California Highway Patrol who have a Napa air base.

Police Academy

[edit]The original San Francisco Police Academy was built in 1895 and was located on the West End adjacent to Golden Gate Park. The building, no longer in use, had the facilities to accommodate 25 trainees. In the 1960s, the building now used as the San Francisco Police Academy Complex was built originally as Diamond Heights Elementary School located at 350 Amber Drive, just behind the Diamond Heights Safeway. The building was built in the 1960s hugging the Diamond Heights/Glen Park Canyon. Almost immediately upon completion, the property was determined to be unsafe and sliding into the canyon. The school was closed for one year, shored up and reopened. It was closed as a public school in the 1980s. Subsequently, the building is used by the SFPD for training. It is surrounded by a heavily wooded forest area and is near a shopping mall and apartment complex. As of recently (2008), there are three academy classes in session annually, with individual classes taking place for 31 to 32 weeks, year round. Pier 94 is also used for vehicle training exercises and mock police car chases, and Lake Merced is the location of the academy's firing range. With a boom in retirees in the coming years[when?], a projected 700+ officers will be hired within the next five to ten years, meaning full academy classes for some time. Lateral officers are currently being hired, and are being hired on an ongoing basis.[28]

Headquarters

[edit]

For 56 years, SFPD headquarters was located at the San Francisco Thomas J. Cahill Hall of Justice at 850 Bryant Street, which houses a number of criminal courts, jail facilities, investigative and support units, as well as "Southern Station".[29] The Headquarters of the San Francisco Sheriff's Department is housed in an adjacent building. On April 16, 2015, the SFPD officially moved its headquarters to a new location at Mission Bay.[30]

In popular culture

[edit]The SFPD has been portrayed in films such as The Sniper, Vertigo, Freebie and the Bean, The Laughing Policeman, Bullitt, the Dirty Harry film series, 48 Hrs., A View to a Kill, Metro, Rush Hour, and Zodiac, as well as television series such as The Lineup (aka San Francisco Beat), Ironside, The Streets of San Francisco, McMillan & Wife, Nash Bridges, The Division, Killer Instinct, The Evidence, Charmed (1998–2006), Murder in the First and Monk. The Dirty Harry film series is known for shaping the popular view of the department, with a hard-nosed stance on crime and often using "cowboy" tactics (shoot first, stakeouts, and preemptive raids).

In the days of old-time radio, there were a number of drama series built around the activities of the SFPD. Carlton E. Morse created four different shows based on SFPD files for NBC's Pacific Coast Network, Chinatown Squad, Barbary Coast Nights, Killed in Action, and To the Best of Their Ability.

The SFPD has also had a strong presence in novels and short stories. Sidney Herschel Small wrote a series of thirty stories that appeared in Detective Fiction Weekly between 1931 and 1936 featuring Sergeant Jimmy Wentworth, the head of the Chinatown Squad, whose adventures were presumably based, if loosely, on the activities of Jack Manion, the real-life commander of SFPD's Chinatown detail. In the early 1960s, Breni James wrote two novels about Sergeant Gun Mattson, uniformed patrol supervisor at the Ingleside District Station, The Night of the Kill (1961), which was an Edgar nominee for Best First Novel, and The Shakeup (1964). Ernest K. Gann's 1963 novel, Of Good and Evil, tells the story of one busy day in the professional life of San Francisco's police chief, Colin Hill, a character apparently modeled on SFPD's real-life chief at that time, Thomas J. Cahill, to whom the book is dedicated. More recently, Collin Wilcox wrote a long series featuring Lieutenant Frank Hastings of SFPD's Homicide Detail. Laurie R. King won an Edgar for her first novel, A Grave Talent (1993), which introduced Homicide Inspector Kate Martinelli, who has gone on to headline such books as With Child (1997), an Edgar nominee, and The Art of Detection (2006), winner of the Lambda Award for Best Lesbian Mystery Novel. James Patterson's novels about Homicide Inspector Lindsay Boxer, introduced in 1st to Die (2001), have become best-sellers, and were the basis for the short-lived TV series Women's Murder Club. Former SFPD detective and current Bay Area private investigator Jerry Kenneally has written two novels featuring Homicide Inspector Jack Kordic, The Conductor (1996) and The Hunted (1999). After a trilogy of police novels set in other parts of the Bay Area, retired San Jose Police Chief Joseph D. McNamara wrote one novel, Code 211 Blue (1996), about a narcotics inspector who uncovers corruption within the SFPD. Another former cop, Robin Burcell, who spent twenty years in law enforcement, first as an officer in the Lodi Police, then later as a criminal investigator for the Sacramento County District Attorney's Office, wrote four novels featuring Homicide Inspector Kate Gillespie, the first of which, Every Move She Makes (1999), won the Barry for Best Paperback Original, and the third of which, Deadly Legacy (2003), won the Anthony in the same category.

Some San Francisco-set police novels have explored The city's rich history. With Siberia Comes a Chill (1990), by former Inyo County Deputy Sheriff Kirk Mitchell, features SFPD Homicide Inspector John Kost who, in April 1945, while conducting a murder investigation as the United Nations is meeting for the first time in San Francisco, finds himself pitted against an NKVD assassin. White Rabbit by David Daniels, set during 1967's Summer of Love, follows Homicide Inspector John Sparrow as he pursues a serial killer stalking the residents of San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood.

A future version of the SFPD play a minor role in a handful of missions in the video game Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, most notably they assist the military in stopping a van carrying drones to destroy the Golden Gate Bridge. Unfortunately they fail, resulting in the destruction of the bridge, pinning down an aircraft carrier. The main protagonist saves one SFPD sergeant from plunging to his death from the wreckage of the bridge. Most main protagonists of the iOS novel Cause of Death are officers of the SFPD. In fact, a main protagonist of the game (Malachi "Mal" Fallon) has his name taken from that of Malachi Fallon of the real SFPD.

The SFPD has been fictionalized in the 2004 video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas as the San Fierro Police Department and in the 2014 animated film Big Hero 6 as the San Fransokyo Police Department. The SFPD were fictionalized in 2016 when the video game Watch Dogs 2 was released.

The Mentalist character Teresa Lisbon is former SFPD.

The character of Beau from Colony is a 30-year veteran of the department.

Sonic the Hedgehog character Tom Wachowski is accepted into joining the SFPD at the beginning of the film, but later decides not to go.

Controversies

[edit]

In 1937, an investigation, referred to as the "Atherton Report,"[31] by District Attorney Matthew Brady found that more than $1 million per year was being pocketed by officers from regular payoffs by prostitution, gambling and other criminal interests. It has also dealt with attacks such as the Preparedness Day Bombing in 1916 and the San Francisco Police Department Park Station bombing in 1970.

On October 6, 1989, SFPD officers initiated a police riot in the Castro District following a peaceful march held by ACT UP to protest the United States government's actions during the ongoing AIDS pandemic. The event, known as the Castro Sweep, resulted in several dozen arrests and numerous injuries.[32]

Recent examples of controversy include racist and homophobic texts Racist, homophobic texts by San Francisco police trigger case reviews, police shootings of citizens, the reaction to Critical Mass bicycle rides and protests in the Financial District against U.S. foreign policy. The rate of complaints against officers and "excessive force" cases are lower relative to other big-city departments, such as the LAPD, the NYPD, or CPD. But the city continues to have one of the highest complaint rates, particularly when analyzed on a per-capita basis, factoring in the relatively small population of San Francisco compared to Los Angeles or New York. This could be attributed to several factors, including the dramatic increase of so-called "transient population", or those coming to visit the city (increasing the population to approximately 1.3 million), or the proactive nature of the Office of Citizen Complaints, or OCC. The OCC, created by San Francisco City Charter, has been known to solicit complaints from people contacted by police.

Notable incidents and events include the Golden Dragon massacre, a deadly shooting between Chinese gang members in the city's Chinatown district; the 101 California Street shootings in 1993; and the death of Aaron Williams while in police custody in 1995. In the latter case, several officers were charged with using excessive force, including Marc Andaya, described as having kicked Williams when he was on the ground. After two years and revelations of numerous complaints and two federal lawsuits against Andaya as an officer with the Oakland Police Department before he moved to San Francisco, in June 1997 Andaya was fired by the San Francisco Police Commission. Van Jones and the Bay City PoliceWatch were credited with organizing and keeping up community pressure against the department on this case.[33]

The crime lab's reputation worsened after an employee was arrested in March 2010 for stealing cocaine. This resulted in hundreds of cases being tossed out of court.[34]

November 20, 2002: A scandal known as Fajitagate occurred when three off-duty police officers—Matthew Tonsing, David Lee, and Alex Fagan Jr.—assaulted two San Francisco residents, Adam Snyder and Jade Santoro, over a bag of fajitas. Alex Fagan Jr. is the son of SFPD Assistant Chief Alex Fagan, who later became Chief. Nine officers and Chief Earl Sanders were involved in a cover-up regarding the fight. This incident has led to a grand jury indictment of the parties involved. However, unable to prove that a cover-up existed, the district attorney dropped the charges against former Chief Earl Sanders. Acting Chief Alex Fagan also resigned. In 2006, a civil jury found former officers Fagan and Tonsing liable for damages suffered in the beating, awarding plaintiffs Snyder and Santoro $41,000 in compensation.

Public Defender Jeff Adachi released video footage from security cameras that showed different cases of SFPD officers entering apartments without warrants, plain-clothed officers not displaying badges, and officers removing belongings that were never accounted for in police reports and other court documents. In March 2011, the FBI opened an investigation into alleged police misconduct.[35] The misconduct resulted in the DA dismissing 57 criminal cases because the scandal had compromised them.[36]

In 2012, 12 employees (sworn or unsworn) of the department were charged with crimes. Seven were cited for drunk driving, three for theft, one for possession of drug paraphernalia and one for unauthorized access to official databases.[37]

Pay

[edit]The SFPD has often been criticized for the high salaries received by staff.[38] Greg Suhr, is the highest-paid police chief in the country, at $321,577.[39] In 2024, an SFPD officer's starting salary is $103,116, rising to $147,628 after seven years of service.[40] Overtime and additional pay often significantly increases these earnings - in 2023, the average starting officer made $170,290 in total pay, and the average level 3 officer made $240,017 in total pay.[41]

2014–2016 texting scandal

[edit]In 2016, Jason Lai and other San Francisco police officers were found to have sent racist texts. Officer Lai turned himself in to be arraigned.[42] The incident was discovered during investigation of an alleged sexual assault involving the Taraval Station.[43]

Justice Department report

[edit]In October 2016, The Justice Department's Office of Community Oriented Policing Services released a 432-page report stating that the SFPD stops and searches African Americans at a higher rate than other groups, and inadequately investigates officers' use of force. They uncovered "numerous indicators of implicit and institutionalized bias against minority groups." A large majority of suspects killed by police were people of color. The report recommended 272 reforms to the department.[13][44]

Lethal force by robots

[edit]In November 2022, the SFPD submitted a draft policy to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, clarifying its intended use of military equipment in order to comply with Assembly Bill 481. Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who later supported the policy, attempted to add "robots shall not be used as a use of force against any person".[45] The SFPD removed this line and went on to defend the use of robots as lethal weapons in emergencies that preclude any other option. An updated version specified that lethal force would have to first be authorized by an officer with the rank of Chief, Deputy or Assistant Chief.[46] The American Civil Liberties Union and Campaign to Stop Killer Robots raised concerns about excessive force becoming easier to justify and urged the board to vote against it.[47] On November 29, the policy passed in an 8–3 vote. Police Chief Bill Scott stated that the department's robots would be piloted manually if any of them were ever used to guide explosives toward a target.[46]

Stations

[edit]The SFPD currently has ten main police stations throughout the city in addition to a number of police substations.

Metro Division:

- 1) Central Station: 766 Vallejo St.

- 2) Mission Station: 630 Valencia St.

- 3) Northern Station: 1125 Fillmore St.

- 4) Southern Station, Public Safety Building: 1251 3rd St.

- 5) Tenderloin Station: 301 Eddy St.

Golden Gate Division:

- 6) Bayview Station: 201 Williams Ave.

- 7) Ingleside Station: 1 Sgt. John V. Young Ln.

- 8) Park Station: 1899 Waller Street

- 9) Richmond Station: 461 6th Ave.

- 10) Taraval Station: 2345 24th Ave.

Sub Station and Special Division

- 11) San Francisco Police Academy: 350 Amber Dr.

- 12) San Francisco International Airport Police: International Terminal, located on fifth floor

Fallen officers

[edit]Since the establishment of the San Francisco Police Department, 102 officers have died in the line of duty.[48]

The causes of death are as follows:

| Cause of death | # of deaths |

|---|---|

| Aircraft accident | 3

|

| Assault | 2

|

| Automobile accident | 6

|

| Bomb | 1

|

| Drowned | 1

|

| Electrocuted | 1

|

| Fall | 1

|

| Gunfire | 59

|

| Gunfire (Accidental) | 2

|

| Heart attack | 2

|

| Motorcycle accident | 6

|

| Stabbed | 2

|

| Struck by streetcar | 3

|

| Struck by vehicle | 4

|

| Vehicle pursuit | 5

|

| Vehicular assault | 2

|

| Weather/Natural disaster | 1

|

Demographics

[edit]- Male: 85.15%

- Female: 14.85%

- White: 49.39%

- Hispanic: 16.46%

- Asian: 16.55%

- African-American/Black: 9.58%

- Filipino: 5.79%

- Native American/ Alaska Native: 0.30%

- Other: 1.35%

- Unknown: 0.57%[49]

The diversity of the department has increased significantly since 1972, when only 150 of the department's 2000 officers were of a non-white background.[50]

SFPD chiefs of police

[edit]| Name | Term | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Malachi Fallon | 1849–1850 | ||

| Brandt Sequine | 1851–? | ||

| John W. McKenzie | ?–1856 | ||

| James F. Curtis | 1856–1858 | ||

| Martin J. Burke | 1858–1866 | ||

| Patrick Crowley | 1866–1873 | ||

| Theodore G. Cockrill | 1873–1875 | ||

| Henry H. Ellis | 1875–1877 | ||

| John Kirkpatrick[51] | 1877–1879 | ||

| Patrick Crowley | 1879–1897 | ||

| Isaiah W. Lees | 1897–1900 | ||

| William P. Sullivan | 1900–1901 | ||

| George Wittman | 1901–1905 | ||

| Jeremiah F. Dinan | 1905–1907 | ||

| William J. Biggy | 1907–1908 | ||

| Jesse B. Cook | 1908–1910 | ||

| John B. Martin | 1910 | ||

| John Seymour | 1910–1911 | ||

| David A. White | 1911–1920 | ||

| Daniel J. O'Brien | 1920–1928 | ||

| William J. Quinn | 1929–1940 | ||

| Charles W. Dullea | 1940–1947 | ||

| Michael Riordan | 1947 | ||

| Michael Mitchell | 1948–1950 | ||

| Michael Gaffey | 1951–1955 | ||

| George Healy | 1955–1956 | ||

| Francis J. Ahern | 1956–1958 | ||

| Thomas J. Cahill | 1958–1970 | ||

| Alfred J. Nelder | 1970–1971 | ||

| Donald M. Scott | 1971–1975 | ||

| Charles Gain | 1975–1980 | ||

| Corneilius P. Murphy | 1980–1986 | ||

| Frank M. Jordan | 1986–1990 | ||

| Willis Casey | 1990–1992 | ||

| Richard D. Hongisto | 1992 | ||

| Anthony Ribera | 1992–1996 | ||

| Fred H. Lau | 1996–2002 | ||

| Prentice E. Sanders | 2002–2003 | ||

| Alex Fagan | 2003–2004 | ||

| Heather Fong | 2004–2009 | ||

| George Gascón | 2009–2011 | ||

| Greg Suhr | 2011–2016 | ||

| Toney Chaplin | 2016 | ||

| William Scott | 2016–present | Source:[52] | |

See also

[edit]- List of law enforcement agencies in California

- San Francisco Police Officers Association

- San Francisco District Attorney's Office

References

[edit]- ^ Sullivan, Carl; Baranauckas, Carla (June 26, 2020). "Here's how much money goes to police departments in largest cities across the U.S." USA Today. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020.

- ^ "Current Employed Full-time Sworn, Reserve & Dispatcher Personnel: All Post Participating Agencies" (PDF). Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training. July 1, 2021.

- ^ Brian A. Reaves; Matthew J. Hick (May 2002). "Police Departments in Large Cities, 1990–2000" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2009.

- ^ Ackerson, Sherman; Dewayne Tully. "SFPD: SFPD History". San Francisco Police Department. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007.

- ^ (De Russailh, Albert Bernard) Crane, Clarkson. Last Adventure- San Francisco in 1851. Translated from the Original Journal of Albert Bernard de Russailh by Clarkson Crane. San Francisco. The Westgate Press. 1931

- ^ a b c d Comment, Emergency Mayoral Power: An Exercise in Charter Interpretation, 65 Cal. L. Rev. 686.

- ^ Crouch, Winston W. (1978). Organized Civil Servants: Public Employer-Employee Relations in California. Berkeley: University of California Press. Archived from the original on June 15, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Comment, Emergency Mayoral Power: An Exercise in Charter Interpretation, 65 Cal. L. Rev. 686. citing San Francisco Chronicle, August 20, 1875, at 1, col. 2.

- ^ a b Crouch, Winston W. (1978). Organized Civil Servants: Public Employer-Employee Relations in California. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 288. Archived from the original on June 15, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "Verreos v. City and County of San Francisco, 63 Cal. App. 3d 86, 133 Cal. Rptr. 649 (Ct. App. 1976)". Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ "Sfgov.org | San Francisco Police Department: Airport Bureau". Archived from the original on October 9, 2009.

- ^ Walker, Noelle (August 15, 2014). "San Francisco Police academy graduates first transgender officer". KTVU. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Zapotosky, Matt (October 12, 2016). "Justice Department report blasts San Francisco police". Retrieved January 5, 2018 – via The Washington Post.

- ^ Asperin, Alexa Mae; Estacio, Terisa (December 5, 2018). "Increased foot patrols in San Francisco led to 'significant' drop in assaults, thefts: study". KRON4. Archived from the original on January 17, 2024.

- ^ Miguel, Ken; Matier, Phil (August 3, 2022). "SFPD chief worries about loss of hundreds of officers amid staffing shortage". ABC7. Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ^ Baustin, Noah (April 8, 2024). "Police seldom write traffic tickets in San Francisco. That's costing the city millions". The San Francisco Standard. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ Medina, Madilynne (April 30, 2024). "SF police to crack down on speeding, ramp up traffic enforcement after historic lows". SFGATE.

- ^ a b Castañeda, Carlos; Martinez, Jose (April 1, 2024). "Watch: Thieves ransack Walgreens store near San Francisco's Civic Center". CBS News Bay Area. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ "Bureaus". SFPD. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ Joshua Johnson (July 25, 2011). "Bayview Shooting: Explaining the Discrepancy Between SFPD Guns and Bullet Found in Kenneth Harding". KQED. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013.

- ^ SFPD Northern Station Captain (July 2012). "The heroes who stand among us". Marina Times.

- ^ Jim Hardin. "The Horror of the "War on Crime" Swat Teams". Geocities. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved September 7, 2011., republishing Christian Parenti (November 18, 1998). ""War" on Crime: The SFPD used SWAT-style equipment to raid a Western Addition housing project. Does military gear encourage military policing?". San Francisco Bay Guardian.

- ^ Policemag.com. Policemag.com. Retrieved September 7, 2011. Archived December 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "San Francisco Housing Authority". Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ Jack Shafer (November 29, 1995). "Crushing CRUSH". SF Weekly. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ George Cothran (November 22, 1995). "C.R.U.S.H. (Part I)". SF Weekly. Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ Garvey, John (October 6, 2004). San Francisco Police Department. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-3076-1.

After the 2000 crash, the SFPD helicopter unit was put into inactive status

- ^ "Lateral Entry Program". San Francisco Police Department. November 5, 2012.

- ^ "Southern Police Station is Moving to the Public Safety Building". San Francisco Police Department. April 14, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

After operating for 56 years from the outdated lobby of 850 Bryant Street, this new state of the art facility will replace the seismically deficient Hall of Justice

- ^ Lee, Vic (March 26, 2015). "SFPD headquarters move to new Mission Bay site". Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Chapot, Hank (February 11, 2012). "The 1937 San Francisco Police Graft Report by Edwin Atherton". Smashwords.

- ^ Koskovich, Gerard, "Remembering a Police Riot: The Castro Sweep of October 6, 1989", in Winston Leyland (ed.), Out in the Castro: Desire, Promise, Activism (San Francisco: Leyland Publications, 2002): pp. 189–198. ISBN 0-943595-88-6

- ^ Ards, Angela (February 18, 1999). "When Cops Are Killers". The Nation. Archived from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Elias, Paul; Collins, Terry (April 18, 2010). "SF crime lab at center of growing scandal". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 24, 2010.

- ^ "FBI to investigate SFPD officers involved in Henry Hotel drug bust". ABC7 San Francisco. March 4, 2011. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023.

- ^ District Attorney Throws Out 57 Cases After Henry Hotel Scandal, Cops Pissed, by Lauren Smiley, March 9, 2011, SF Weekly

- ^ "Extracurricular Activities: Public Servant Misconduct in 2012", by Joe Eskenazi, December 26, 2012, SF Weekly

- ^ Shih, Gerry (March 26, 2010). "As Budget Gaps Widen, San Francisco Police Salaries Grow". New York Times. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

Three years ago, Gary P. Delagnes, the president of the San Francisco Police Officers Association, made a bullish prediction after successfully negotiating a lucrative four-year contract: After a scheduled 4 percent pay raise phased in on July 1, 2010, Mr. Delagnes wrote in a note to the officers, the force would most likely fulfill a 20-year mission to become the "highest paid major police department in the country." Now, his prediction may be coming true, but at the worst possible time. ... economists at the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that the 2009 average hourly wage of San Francisco officers was about 67 percent higher than the national average, 15 percent above that of officers in Los Angeles and 18 percent higher than in San Diego. ... Criticism of police pay and benefits is hardly unprecedented. For decades, the Police Department has weathered intermittent attacks, only to emerge with its compensation largely unaffected. During the 1990s and early 2000s, the debate over the department's generous pensions occasionally grew heated. Officers who have served 30 years are now eligible for pensions at 90 percent of their salary in their final year.

- ^ Wilkey, Robin (August 26, 2012). "Greg Suhr, San Francisco Police Chief, Highest-Paid Cop in Nation". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ^ "Salary and Benefits". San Francisco Police Department. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

San Francisco offers excellent benefits and the current starting salary is $103,116 per year. After seven years of service, a Police Officer may earn up to $147,628 per year.

- ^ "Job title summary for San Francisco (2023)". Transparent California. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ Scott Glover; Dan Simon (April 26, 2016). "'Wild animals': Racist texts sent by San Francisco police officer, documents show". CNN. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024.

- ^ Lee, Fiona (April 1, 2016). "Investigation of Taraval Station Officer Uncovers Racist SFPD Texts". Hoodline. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023.

- ^ Williams, Timothy (July 11, 2016). "San Francisco Police Disproportionately Search African-Americans, Report Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Jarrett, Will (November 22, 2022). "SFPB authorized to kill suspects using robots in draft policy". Mission Local. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Boyette, Chris (November 30, 2022). "San Francisco supervisors vote to allow police to use robots to kill". CNN. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "San Francisco to allow police 'killer robots'". BBC. December 1, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "San Francisco Police Department, California, Fallen Officers", Officer Down Memorial Page, Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ "San Francisco Police Department Department Statistics Report" (PDF). San Francisco Police Department. July 2018.

- ^ "San Francisco – News – Earl's Last Laugh". SF Weekly. (February 21, 2007). Retrieved September 7, 2011.

- ^ Kevin Mullen, "History of the Chinatown Squad", Part 4[permanent dead link], POA Journal, December 1, 2007

- ^ "Reformers 'invigorated' by new SFPD chief". December 21, 2016. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Elliot, Bryn (March–April 1997). "Bears in the Air: The US Air Police Perspective". Air Enthusiast. No. 68. pp. 46–51. ISSN 0143-5450.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- San Francisco Police Patrol Specials

- San Francisco Police Officer Association

- SFPD Gallery of Pictures

- Jesse Brown Cook Scrapbooks Documenting San Francisco History and Law Enforcement (ca. 1895–1936) online archive, The Bancroft Library

- 1860-1870s Picture of a San Francisco Police officer