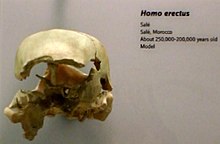

Salé cranium

| |

| Catalog no. | Salé |

|---|---|

| Common name | Salé cranium |

| Species | Homo sapiens? |

| Age | 400-200 ka |

| Place discovered | Salé, Morocco |

| Date discovered | 1971 |

| Discovered by | Quarrymen |

The Salé cranium is a pathological specimen of enigmatic Middle Pleistocene hominin[1] discovered from Salé, Morocco by quarrymen in 1971.[2] Since its discovery, the specimen has variously been classified as Homo sapiens, Homo erectus,[3] Homo rhodesiensis/bodoensis,[4][5] or Homo heidelbergensis. Its pathological condition and mosaic anatomy has proved difficult to classify. It was discovered with few faunal fossils and no lithics, tentatively dated to 400 ka by some sources.[6]

History

[edit]The specimen was discovered in 1971 during mining of salt sandstones, uncovering a cranial vault and partial maxilla with teeth.[3] These sandstones probably belong to the Tensiftian, although its position within it is debated. Some suggest that the human remains belong to the lower end of the cycle.[7]

Description

[edit]Clarke (1990) compared the skull with Ndutu, finding commonalities with the rear of the skull especially.[3] In 1981, the cast reconstruction of the skull was revised, removing large sums of plasticine and closing previously-opened gaps between fragments. During this process, the endocast was studied and measured, revealing strange 'dimples' of the anterior frontal lobe. This trait is shared with the Irhoud and Spy hominins. As well, the transverse sinus is right in this fossil and Irhoud, but the opposite for Spy for unknown reasons. Previous studied suggested a cranial capacity of 930-960, but Holloway (1981) suggests a revised metric of 880 cc. Posteriorly, the parietal bossing is significant.[8]

Pathology

[edit]The specimen is suggested to have been female that reached adulthood, despite having pathologies in the cranium that distorted its shape. This was probably caused by muscular trauma that was related to congenital torticollis, that being a lack of amniotic fluid and fetal confinement during gestation. As such, the skull is deformed and asymmetrical, which would have reduced mobility in the neck. In living people, the rate of these types of pathologies is extremely low, about 2%. Hublin (2009) argues that ancient people who suffered this may were able to survive many years, into adulthood as this specimen shows, and Middle Pleistocene people may have had a more 'modern' life history.[9] The occipital and poorly-developed transverse torus are caused by the deformation.[4]

Classification

[edit]Jaeger (1975) suggested that the specimen shared traits between modern humans and Homo erectus, suggesting that it be assigned to H. erectus based on platycephaly, brain size, skull dimensions, the "maximum transverse diameter basally situated", sagittal keeling, postorbital constriction and tooth dimensions. Stringer et al. (1979) suggested that this skull may have belonged to a grade of crania represented by Bodo, Broken Hill, Hopefield, Eyasi, Cave of Hearths, Rabat, and possibly Sidi Abderrahman and Thomas Quarry to represent "archaic Homo sapiens".[3] Debénath et al. (1982) suggested that the skull can be placed close to the mandibles from Tighenif belonging to a ghost lineage of Homo erectus.[7]

Hublin (1985) suggested an age of 400 ka and agreed on the species classification, except for the characters Jaeger extracted from the occipital, as he thought it appeared abnormal. Instead, Hublin focused on the basisphenoid, basioccipital, gracile temporal, and developed parietal bossing. Clarke examined the specimen in 1984 and found similarities with Ndutu in the top-down build, supramastoid, and numerous features of the parietal and temporal. In Clarke's opinion, the two crania were of similar age and had similar traits.[3] Later studies determined that the occipital was pathological from a congenital deformation,[10] muddying classification.[6]

Zeitoun et al. (2010) classify the specimen alongside the Homo sapiens specimens Irhoud without clarification.[11] In recent, the specimen is associated with early Homo sapiens specimens such as Ngaloba, Florisbad. In addition, Hublin (1985, 2001) suggests that the skull has "clear synapomorphies" with Homo sapiens (frontals, squama, parietal bossing, vault wall orientation, a defined tuberculum pharyngeum, a sphenoid spine being present, preglenoid plane orientation) and Rightmire (1990) added traits of the basisphenoid, glenoid, and tympanic. Bräuer (2012) adds that similarity to Ndutu is still present, classifying the specimens as, possibly, Homo sapiens rhodesiensis or Homo sapiens sensu lato as a grade transitioning to a 'modern' form via, possibly, an accretion scenario.[4]

Since these studies, the Ndutu cranium has been heavily reconstructed and revised in 2023. The results of that work discovered that despite the specimens classification history, it is most morphologically similar to the hominins at Sima de los Huesos, especially cranium 5. They also state that recent work by Stringer posits that fossils attributed to Homo heidelbergensis and associated with Africa may have been a European side-branch descending from Neanderthals and not having connection to Homo sapiens.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Rightmire, G. Philip (2009-09-22). "Middle and later Pleistocene hominins in Africa and Southwest Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16046–16050. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10616046R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903930106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2752549. PMID 19581595.

- ^ "Artifact Scans | The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program". humanorigins.si.edu. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- ^ a b c d e Clarke, R.J. (1990). "The Ndutu cranium and the origin of Homo sapiens". Journal of Human Evolution. 19 (6–7): 699–736. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(90)90004-U.

- ^ a b c Bräuer, G. (2012), Hublin, Jean-Jacques; McPherron, Shannon P. (eds.), "Middle Pleistocene Diversity in Africa and the Origin of Modern Humans", Modern Origins, Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 221–240, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2929-2_15, ISBN 978-94-007-2928-5, retrieved 2023-08-13

- ^ Roksandic, Mirjana; Radović, Predrag; Wu, Xiu-Jie; Bae, Christopher J. (2022). "Resolving the "muddle in the middle": The case for Homo bodoensis sp. nov". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 31 (1): 20–29. doi:10.1002/evan.21929. ISSN 1060-1538. PMC 9297855. PMID 34710249.

- ^ a b "Salé | Paleoanthropology, Prehistory, Fossils | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- ^ a b Debénath, André; Reynal, Jean-Paul; Texier, Jean-Pierre (1982). "Position stratigraphique des restes humains paléolithiques marocains sur la base des travaux récents". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. 2: 1247–1250.

- ^ Holloway, Ralph L. (1981). "Volumetric and asymmetry determinations on recent hominid endocasts: Spy I and II, Djebel Ihroud I, and the salèHomo erectus specimens, with some notes on neandertal brain size". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 55 (3): 385–393. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330550312. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 6791506.

- ^ Hublin, Jean-Jacques (2009-04-21). "The prehistory of compassion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (16): 6429–6430. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.6429H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0902614106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2672542. PMID 19380715.

- ^ Gracia, Ana; Martínez-Lage, Juan F.; Arsuaga, Juan-Luis; Martínez, Ignacio; Lorenzo, Carlos; Pérez-Espejo, Miguel-Ángel (2010-06-01). "The earliest evidence of true lambdoid craniosynostosis: the case of "Benjamina", a Homo heidelbergensis child". Child's Nervous System. 26 (6): 723–727. doi:10.1007/s00381-010-1133-y. ISSN 1433-0350. PMID 20361331. S2CID 33720448.

- ^ Zeitoun, Valery; Détroit, Florent; Grimaud-Hervé, Dominique; Widianto, Harry (2010-09-01). "Solo man in question: Convergent views to split Indonesian Homo erectus in two categories". Quaternary International. Oldest Human Expansions in Eurasia: Favouring and Limiting Factors. 223–224: 281–292. Bibcode:2010QuInt.223..281Z. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2010.01.018. ISSN 1040-6182. S2CID 84764668.

- ^ Montiel, Gustavo; Lorenzo, Carlos (2023). "A New Virtual Reconstruction of the Ndutu Cranium". Heritage. 6 (3): 2822–2850. doi:10.3390/heritage6030151. ISSN 2571-9408.