Saint Bieuzy

Saint Bieuzy was a 6th-century Breton hermit and companion of Saint Gildas who gave his name to the villages of Bieuzy (also known as Bieuzy-les-Eaux) and Bieuzy-Lanvaux, both in Morbihan. His name probably comes from the Old Breton biu, bihui, "living". His feast day is 24 November.[1]

Life

[edit]Bieuzy was, it is said, a native of Great Britain who migrated to Brittany, and there became a hermit and a disciple of Saint Gildas.[2] Tradition relates that in the year 538 Bieuzy went up the Blavet valley in the company of Gildas (who had previously founded the monastery of Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys): they established a hermitage or oratory consisting of a natural cave in a huge pile of rocks on the banks of the Blavet near Castennec.[3][4] A few years later, Gildas returned to Rhuys, but Bieuzy remained, setting up a school nearby, around which a few inhabitants settled, at a place which has since become the village of Bieuzy. The establishments created by Gildas and Bieuzy were destroyed during the Norman invasions in the 9th or 10th century.[5] Gildas and Bieuzy's oratory was refounded in the 16th century as the Chapelle Saint-Gildas.[6] Saint Bieuzy became known as a holy healer of rabies, locally called le mal de Saint Bieuzy.[7]

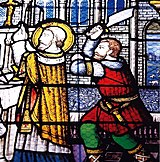

According to the hagiographer Guy Autret de Missirien, Saint Bieuzy performed a curious miracle. Around 570, a servant asked him to interrupt his mass to go and heal his lord's pack of dogs suffering from rabies, but Bieuzy refused. The furious Breton lord came to split his skull with a sword (an axe, knife or cutlass according to other versions of the legend), the blow being so violent that the weapon remained planted there. Bieuzy found the strength to walk 80 kilometres (50 mi) to the abbey of Rhuys where he died under the blessing of his master, Saint Gildas. During his journey to the abbey, Bieuzy is said to have spent a night in Bieuzy-Lanvaux (near Pluvigner) with the axe still embedded in his skull. The spring of Bieuzy-Lanvaux has since this event been under the protection of the holy healer of rabies and migraines. The legend also tells that the Breton lord, on his return home, found that all his horses and farm animals had gone mad; the dogs bit the tyrant and his servants to death.[8]

His cult in Brittany

[edit]- Bieuzy is the patron saint of Bieuzy (Bieuzy-les-Eaux) in Morbihan, and of Saint-Bihy near Quintin in Côtes-d'Armor.[9]

- The former parish of Bihoué in Morbihan was dedicated to Saint Bieuzy. It later became a trève, or sub-division of a parish, integrated into the parish of Quéven in Morbihan.[10]

- Saint Bieuzy's head is preserved in a reliquary at the Chapelle de Notre-Dame-des-Orties in the parish of Pluvigner.[11]

A number of springs in Brittany are dedicated to him:

- The Fontaine de Saint-Bieuzy (in Bieuzy), built in the 16th century by the Rimaison family, whose coat of arms is at the top of the fountain. The source of the Saint-Bieuzy fountain would cure rabies in any dog that has just been bitten, and also toothache in a man provided that he goes around the aedicule three times with his mouth full of water.[12] The statuette of Saint Bieuzy which occupied the niche at the centre of the fountain has disappeared since 1974.[13]

- The Bieuzy-Lanvaux spring in Pluvigner cures sufferers from toothache so long as they walk around the spring with water in the mouth.[14]

- The Saint-Bieuzy spring in Ploemeur, Morbihan (a hamlet in this commune also bears the name of Saint-Bieuzy). The spring is located about 300 metres east of this village; built in 1826, it was subsequently forgotten, lost in the brush, before being restored by a local association; "In the 19th century, mothers came to the spring with their babies (probably about a year old). After washing their clothes there, they went around the spring three times with their child in their arms. This was supposed to give strength to the child, who would be walking a few days later."[15]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Stéphan, Alain (1996). Tous les prénoms bretons (in French). [Luçon]: Jean-Paul Gisserot. pp. 23–24. ISBN 2877473953. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ A Menology of England and Wales; or, Brief Memorials of the Ancient British and English Saints. London: Burns & Oates. 1892. p. 564. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Le Mené, Jh-M (1888). Histoire du Diocèse de Vannes. Tome 1 (in French). Vannes: Eugène Lafolye. pp. 75–76. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Rosenzweig, [Louis Théophile] (1860). "Statistique archéologique de l'arondissement de Napoléonville". Bulletin de la Société Polymathique du Morbihan (in French): 19. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Floquet, Charles (1982). Au coeur de l'Argoat: La Bretagne intérieure (in French). Paris: France-Empire. p. 24. ISBN 9782856993873.

- ^ Duhem, Gustave (1932). Morbihan (in French). Paris: Letouzey et Ané. p. 15. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Luco, Abbé (1875). "Les paroisses". Bulletin de la Société Polymathique du Morbihan (in French): 208. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Dag'Naud, Alain (1993). Lieux insolites et secrets de toutes les Bretagne (in French). [Luçon]: Jean-Paul Gisserot. p. 24. ISBN 2877472132. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ "Saint Bieuzy (VIe siècle)". Nominis (in French). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Bihoué, berceau de Quéven" (PDF). Quéven Kewenn (in French). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ de Corson, Guillotin (1892). Récits de Bretagne. Deuxième serie (in French). Rennes: J. Plihon et L. Hervé. p. 113. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Poulain, Albert; Rio, Bernard (2008). Fontaines de Bretagne. Histoire, légendes, magie, médecine, religion, architecture (in French). Fouesnant: Yoran Embanner. p. 31. ISBN 9782916579153.

- ^ Base Mérimée: Fontaine de dévotion saint Bieuzy (Bieuzy fusionnée en Pluméliau-Bieuzy en 2019), Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ de Corson, Guillotin (1895). "Les pardons et pèlerinages du pays de Vannes". La Revue Morbihannaise (in French). 5: 156. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ Le Lan, Jean-Yves (14 February 2013). "Quatre fontaines racontent leur histoire". Ouest-France (in French). Rennes. Retrieved 24 January 2023.