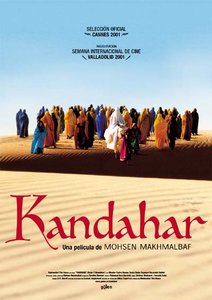

Kandahar (2001 film)

| Kandahar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Mohsen Makhmalbaf |

| Written by | Mohsen Makhmalbaf |

| Produced by | Mohsen Makhmalbaf |

| Starring | Nelofer Pazira Sadou Teymouri Hoyatala Hakimi Dawud Salahuddin (Hassan Tantai) |

| Cinematography | Ebrahim Ghafori |

| Edited by | Mohsen Makhmalbaf |

| Music by | Mohammad Reza Darvishi |

| Distributed by | Avatar Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 85 minutes |

| Country | Iran |

| Languages | Dari language English Pashto Polish |

Kandahar (Dari: قندهار, "Qandahar") is a 2001 Iranian film directed by Mohsen Makhmalbaf, set in Afghanistan during the rule of the Taliban. Its original Afghan title is Safar-e Ghandehar (سفر قندهار), which means "Journey to Kandahar", and it is alternatively known as The Sun Behind the Moon. The film is based on a partly true, partly fictionalized story of Nafas, a successful Afghan-Canadian woman played by Nelofer Pazira.

The film recounts the attempts of Nafas to return to Afghanistan after receiving a letter from her sister, who was left behind when the family escaped from Afghanistan years earlier. Nafas makes this desperate mission in an effort to rescue her sister, who has written in her letter that she plans to commit suicide on the last solar eclipse of the millennium.

Kandahar was filmed mostly in Iran, including at the Niatak refugee camp,[1] but also secretly in Afghanistan itself.[2] Most people, including Nelofer Pazira, played themselves.

Plot

[edit]Nafas, an Afghan woman living in safety in Canada, arrives in Iran, dons a burqa, and enters Afghanistan posing as a wife in a family of refugees attempting to return to their homeland. Brigands rob them along the road to Kandahar. They decide to return to Iran, but Nafas must continue on her mission to save her maimed sister from suicide. She pays Khak, a boy recently expelled from a Qur'anic school, to be her guide. Khak brings Nafas to a village doctor when she gets sick from drinking unsanitized well water. The doctor reveals himself to be an African American convert to Islam, who must wear a fake beard (which he calls "a man's burqa") because he can't grow one. Out of fear of being found out, Khak is dismissed, and the doctor takes Nafas by horse cart. Along the way, he confides with her that he has no formal medical training and has become disillusioned with the turn the country has taken under the Taliban.

Along her journey, Nafas records her impressions into a portable tape recorder in a country where the only technological progress allowed is weaponry. Nafas learns more and more about the hardships women face; and even more so, how years of war have destroyed Afghan society. She sees children robbing corpses to survive, people fighting over artificial limbs that they might need in case they walk through a minefield, and doctors who examine female patients from behind a curtain with a hole in it.

When the doctor turns back because he is afraid to enter Kandahar, she follows a man wearing a burqa who scammed a pair of artificial legs out of the Red Cross. The pair join a wedding party which is stopped by the Taliban because they are singing and playing instruments which is forbidden by law. Her guide is unveiled and taken away. Nafas is cleared by the Taliban patrol to continue, along with other members of the wedding party. In the end, Nafas is within sight of Kandahar at sunset, but she is now a prisoner of the veil.

Dawud Salahuddin

[edit]The film stars Dawud Salahuddin (credited in the film as Hassan Tantai), an American-born convert to Islam who in 1980 assassinated an Iranian dissident and ex-diplomat at the behest of the newly formed Islamic Republic of Iran's intelligence authorities.[3] Makhmalbaf stated that Salahuddin "is also a victim - a victim of the ideal he believed in. His humanity, when he opened fire against his ideological enemy, was martyred by his idealism."[4]

Cast

[edit]- Nelofer Pazira as Nafas

- Hassan Tantai (Dawud Salahuddin) as Tabib Sahid

- Sadou Teymouri as Khak

- Hoyatala Hakimi as Hayat

- Ike Ogut as Naghadar

Reception

[edit]The film premiered at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival,[5] but did not get much attention at first. After the September 11 attacks in 2001, however, it was widely shown.

Kandahar won Makhmalbaf the Federico Fellini Prize from UNESCO in 2001. It won four other awards, and nominations for another six. Other awards won included:

- Freedom of Expression Award - National Board of Review, USA 2001

- Prize of the Ecumenical Jury, to Mohsen Makhmalbaf - Cannes Film Festival 2001

- FIPRESCI Prize to Mohsen Makhmalbaf, "for a visionary, poetic, yet unsparing revelation of human suffering in conflict-torn Afghanistan." - Thessaloniki Film Festival 2001

- Audience Award, for Best Female Voice, to Sabrina Duranti, "for the dubbing of Nelofer Pazira." - Il Festival Nazionale del Doppiaggio Voci nell'Ombra 2002

It is one of the "All-Time" 100 Movies by the periodical Time.[6] As of 28 August 2021, 6,669 IMDb users had given it a weighted average vote of 6.8 out of 10.[7] The film's popularity in Italy saw it gross $4.5 million.[8]

Documentary

[edit]Kandahar was inspired by an unsuccessful attempt that Nelofer made in 1996 to return to Afghanistan to find her lost childhood friend, Dyana, while Afghanistan was still under Taliban rule. The film combines elements of this true story with fiction, e.g. while in reality Nelofer went to search for her friend, the film presents Nafas searching for her sister.

Another attempt by Nelofer to visit Afghanistan to search for her childhood friend was made into the 65 minute documentary Return to Kandahar (2003), produced by Paul Jay and Nelofer Pazira. It portrays Nelofer's actual return from Canada to Afghanistan in 2002, following the fall of the Taliban government. In the documentary, Nelofer returns to Kabul, Kandahar, and Masir-e-Sharif, 13 years after she fled with her family in 1989 at the age of 16. She eventually finds Dyana's family, and learns that her friend had tragically taken her own life several years earlier. The documentary weaves together Nelofer's personal story with that of Afghanistan itself.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mario Falsetto, Liza Béar. The Making of Alternative Cinema: Beyond the frame : dialogues with world filmmakers. Praeger, 2008. ISBN 0-275-99941-6, ISBN 978-0-275-99941-4. Pg 227

- ^ Ingman, Marrit (1 March 2002). "Kandahar - Movie Review". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Nugent, Benjamin (19 December 2001). "A Killer in "Kandahar?"". Time. Archived from the original on March 10, 2005. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Makhmalbaf, Mohsen (12 June 2002). "The condemned". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Kandahar". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (14 January 2010). "Kandahar". Time. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ Kandahar (2001), IMDb. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Rooney, David (24 December 2001). "Homegrown pix gain in Europe". Variety. p. 7.

- ^ Jay, Paul. Return to Kandahar – a film by Paul Jay and Nelofer Pazira. theAnalysis.news, 15 August 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2021.