SS Kronprinz Wilhelm

SS Kronprinz Wilhelm

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Kronprinz Wilhelm |

| Namesake | Crown Prince William |

| Operator | Norddeutscher Lloyd |

| Port of registry | |

| Builder | AG Vulcan, Stettin, Germany |

| Yard number | 522 |

| Launched | 30 March 1901 |

| Maiden voyage | 17 September 1901 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Commissioned into the Imperial German Navy, August 1914 |

| Name | SMS Kronprinz Wilhelm |

| Commissioned | August 1914 |

| Fate |

|

| Name | USS Von Steuben |

| Namesake | Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben |

| Acquired | Seized, 6 April 1917 |

| Decommissioned | 13 October 1919 |

| Renamed | Von Steuben, 9 June 1917 |

| Stricken | 14 October 1919 |

| Identification | ID-3017 |

| Fate | Scrapped, 1923 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Kaiser-class ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 14,908 GRT, 6,162 NRT |

| Displacement | 24,900 tons[1] |

| Length | |

| Beam | 66.3 ft (20.2 m) |

| Draft | 28 ft (8.5 m) |

| Depth | 39.3 ft (12.0 m) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 23.09 kn (26.57 mph; 42.76 km/h) |

| Capacity |

|

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

Kronprinz Wilhelm was a German ocean liner built for Norddeutscher Lloyd, a shipping company now part of Hapag-Lloyd, by the AG Vulcan shipyard in Stettin, Germany (now Szczecin, Poland), in 1901. She was named after Crown Prince Wilhelm, son of the German Emperor Wilhelm II, and was a sister ship of SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse.

She had a varied career, starting off as a world-record-holding passenger liner, then becoming an auxiliary warship from 1914–1915 for the Imperial German Navy, sailing as a commerce raider for a year, and then interned in the United States when she ran out of supplies. When the US entered World War I, she was seized and renamed USS Von Steuben, and served as a United States Navy troop transport until she was decommissioned. She was then turned over to the United States Shipping Board, where she remained in service until she was scrapped in 1923.

German passenger liner (1901–1914)

[edit]

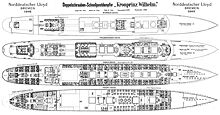

Kronprinz Wilhelm was launched on 30 March 1901. Her registered length was 637.3 ft (194.2 m), her beam was 66.3 ft (20.2 m) and her depth was 39.3 ft (12.0 m). Her tonnages were 14,908 GRT and 6,162 NRT. She had two screws, each driven by a six-cylinder quadruple expansion engine. Between them her twin engines were rated at 3,534 NHP.[4]

She started her transatlantic maiden voyage on 17 September 1901 from Bremerhaven via Southampton and Cherbourg to New York. She was one of the fastest and most luxurious liners on the North Atlantic and stayed on that run until 1914. Her total cost in 1901 was approximately $3.2 million, half a million more than her predecessor Kaiser Wilhelm der Große.[5]

The ship had a Marconi wireless telegraph,[6] and by 1913 her call sign was DKP.[7] She had electric central heating, and 1,900 electric lamps.[8] About 60 electric motors worked bridge cranes, fans, elevators, refrigerators and auxiliary machinery. Kronprinz Wilhelm had a control panel in the map room to close or open the 20 watertight doors.[9] If a door was closed, this was shown by a lamp. This security system alone needed 3.2 km (2.0 mi) of special cables and 1.2 km (0.75 mi) of normal cables. At one point in 1907 the ship rammed an iceberg and suffered a crushed bow, but was still able to complete her voyage.

On 18 September 1901 Kronprinz Wilhelm was damaged on its maiden voyage from Cherbourg to New York by a huge rogue wave. The wave struck the ship head-on.[10] In 1902, she was involved in two different collisions in the waters off Southampton. In the first, she collided with the cargo vessel Robert Ingham in foggy weather. The cargo ship sank, with two fatalities, but Kronprinz Wilhelm sustained little damage. On October 8, 1902, Kronprinz Wilhelm collided with a Royal Navy destroyer, HMS Wizard. The two vessels were pulled into contact with each other when Wizard tried to pass the much larger Kronprinz Wilhelm. Wizard sustained heavy damage, but Kronprinz Wilhelm escaped relatively unharmed.[11]

In September 1902, captained by August Richter, Kronprinz Wilhelm won the Blue Riband for the fastest crossing yet from Cherbourg to New York in a time of five days, 11 hours, 57 minutes, with an average speed of 23.09 kn (42.76 km/h; 26.57 mph).

In her time as a passenger liner, many famous international personalities sailed on Kronprinz Wilhelm. These included the lawyer and politician Lewis Stuyvesant Chanler (1903),[12] the opera singer Lillian Blauvelt (1903),[12] the theatrical manager and producer Charles Frohman (1904) who died in 1915 aboard RMS Lusitania; businessman John Jacob Astor (1906) who died in 1912 aboard RMS Titanic; the "most picturesque woman in America," Rita de Acosta Lydig, and her second husband, Captain Philip M. Lydig (1907);[13] the author Lloyd Osbourne (1907);[13] the star conductor Alfred Hertz (1909); the ballerina Adeline Genée (1908); the theatrical and opera producer Oscar Hammerstein together with the conductor Cleofonte Campanini and the opera singers Mario Sammarco, Giuseppe Taccani and Fernando Gianoli-Galetti (1909);[14][15] and the multi-millionaire, politician and lawyer Samuel Untermyer (1910).

Interiors

[edit]The interiors of Kronprinz Wilhelm were designed by Johann Poppe, the chief interior designer for Norddeutscher Lloyd's liners between 1881 and 1907. Cunard executives who visited the Kronprinz and the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse in 1903 described Poppe's interiors as "bizarre, extravagant and crude, loud in colour and restless in form, obviously costly, and showy to an extreme degree."[16]

Kronprinz Wilhelm offered its First Class passengers such public rooms as a social hall, a music room, smoking room, and library. The dining room could seat 414 and was topped by a glass skylight set within a cupola. The walls consisted of green and bronze panels, while the ceilings were painted with allegories of the four seasons, day and night, etc.[17] The library and smoking room were both decorated in the Renaissance style.[18] The Smoking Room was crowned by a glass dome and paneled and furnished in blue-stained oak, with oak beams supporting the ceiling. Paintings showing episodes from the history of the House of Hohenzollern were placed along the walls.[17]

The Scientific American Supplement noted that "the accommodations are finished on the same rich scale of decoration which obtains on the "Kaiser Wilhelm:" but with the difference that the color scheme is more subdued and, therefore, more restful to the eye."[19] The finest accommodation aboard were 4 "cabines de luxe" consisting of sitting room, several bedrooms and a bathroom, and 8 staterooms with an en-suite bathroom.[18]

State visit of 1902

[edit]

In 1902, Prince Heinrich of Prussia (1862–1929)—brother of Kaiser Wilhelm II—made a state visit to New York, where he was received by President Theodore Roosevelt. Media-oriented, he sailed on the new, impressive Kronprinz Wilhelm, on which a huge number of reporters could accompany him, and not the imperial yacht. There were also 300 passengers and 700 steerage passengers aboard. This state visit was also an early example of film reporting. This was also the ship's first voyage under Captain August Richter, who was the captain until August 1907.

On 9 May 1904, the Kronprinz Wilhelm anchored off Plymouth for passengers and mail to be put ashore by tender, sparking a race between the Great Western Railway (who had the contract to carry the mail) and the London and South Western Railway (who had the passenger contract) to see who would be the first to get the mail/passengers to London. The race was won by the GWR, whose locomotive City of Truro was recorded at 102.3 mph during the descent of Wellington Bank in Somerset. It was claimed by recorder Charles Rous-Marten that gold was transferred from the Kronprinz Wilhelm to the GWR train, as a payment to the French for the construction costs of the Panama canal. However this is doubtful as any gold bound for France would have been offloaded in France rather than England, and the Kronprinz Wilhelm was not moored off Plymouth long enough for this quantity of gold to have been unloaded.

German auxiliary cruiser (1914–1915)

[edit]When Germany entered World War I, Kronprinz Wilhelm was on the western side of the Atlantic, under the command of Captain Grahn. She was commissioned into the Imperial German Navy, and ordered to rendezvous with SMS Karlsruhe to take on two 88 mm (3.46 in) rapid-firing guns[citation needed], 290 rounds of 88 mm ammunition, a machine gun, and 36 rifles as well as one officer, two non-commissioned officers, and 13 ratings. She was commissioned as an auxiliary cruiser.[21] Lieutenant Commander (Kapitanleutnant) Paul Thierfelder—formerly Karlsruhe's navigation officer—became her commander, and Grahn was made 1st Officer.

The close proximity of the British cruiser HMS Suffolk abbreviated the rendezvous, forcing the two German ships to cast off hastily and speed away in different directions. Kronprinz Wilhelm took a meandering course towards the Azores, arriving on 17 August and rendezvousing with the German steamship Walhalla off São Miguel Island.

Provisioning and training

[edit]

Walhalla and Kronprinz Wilhelm headed south from the Azores, while transferring coal from Walhalla to Kronprinz Wilhelm.[22] She then learned from German representatives at Las Palmas in the Canary Islands that no further coal would be available in the neighborhood of the Azores and the Canaries. Consequently, her commanding officer decided to head for the Brazilian coast, where he hoped to find sources of coal more friendly to Germany or at least a greater choice of neutral ports in which to intern his ship if she should find herself unable to replenish her supplies from captured ships.

On the voyage to the Azores and thence to the South American coast, Kronprinz Wilhelm had to avoid contact with all shipping since she was not ready to embark upon her mission raiding Allied commerce. The guns had to be emplaced and a target for gunnery practice constructed. The crew—mostly reservists and civilians—received a crash course in their duties in a warship and in general naval discipline. A "prize crew" was selected and trained in the techniques of boarding captured vessels (prizes), inspecting cargo and ship's papers, and using explosive charges to sink captured ships. Finally, all members of the crew were outfitted in some semblance of a naval uniform.

The crew worked at a feverish pace in order to be ready, and by the time Kronprinz Wilhelm met Karlsruhe's tender—SS Asuncion—near Rocas Reef north of Cape San Roque on 3 September, preparations were nearly complete. At 20:30 the following evening, the auxiliary cruiser encountered a target, the British steamship Indian Prince. The merchantman stopped without the raider's firing a shot. Heavy seas, however, postponed the boarding until shortly after 06:00 the following morning. The prize crew found a cargo composed largely of contraband, but before sinking the ship, Commander Thierfelder wanted to salvage as much of her supplies and fuel as he could. Continued heavy seas precluded the transfer until the afternoon of 8 September. Indian Prince's crew and passengers were brought over to Kronprinz Wilhelm at around 14:00, and the two ships moved alongside each other immediately thereafter. Coaling started and continued throughout the night of 8/9 September. The following morning, the German prize crew detonated three explosive charges which sank Indian Prince. Kronprinz Wilhelm then headed south to rendezvous with several German supply ships.

Coal, more than any other factor, proved to be the key to the success of Kronprinz Wilhelm's cruise. The hope of finding that commodity had brought her to the coast of South America, and her success in locating sources of it kept her there. Initially, she replenished from German steamships sent out of South American ports specifically for that purpose. She spent the next month coaling from four such auxiliaries before she even contacted her next victim. That event occurred on 7 October, when she hailed the British steamship La Correntina well off the Brazilian coast at about the same latitude as Rio de Janeiro. The next day, the raider went alongside the captured ship to seize the prize's coal and cargo of frozen meat before sinking her. She took La Correntina's two ammunition-less 4.7 in (120 mm) guns and their splinter shields. The raider later mounted the additional guns aft, where they were used for gun drills and to fire warning shots with modified, blank salute cartridges. She continued coaling and provisioning operations from La Correntina until 11 October, when bad weather forced a postponement. On 14 October, she resumed the transfer of fuel but broke off again when she intercepted a wireless message indicating that her captive's sister ship La Rosarina had departed Montevideo two days earlier and would soon pass nearby. The prize crew placed the usual three explosive charges, and sank La Correntina that same day. Survivors of La Correntina and the French barque Union were landed at Montevideo by the German liner Sierra Cordoba on 23 November 1914.[23]

For the next five months, Kronprinz Wilhelm cruised the waters off the coast of Brazil and Argentina. Allied newspapers often reported that Kronprinz Wilhelm had been sunk, torpedoed, or interned, but between 4 September 1914 and 28 March 1915, she was responsible for the capture (and often sinking) of 15 ships—10 British, four French, and one Norwegian—off the east coast of South America. Thirteen of them sank from direct actions of Kronprinz Wilhelm; another she damaged severely by ramming, and she probably sank later. The remaining ship served as a lumpensammler, transporting into port what had become an unbearable number of detainees aboard after her 12th capture.

Methods of capture

[edit]Ships were usually captured either by Kronprinz Wilhelm simply overtaking them with superior speed and size, ordering them to stop, and then sending over a boarding party, or by pretending to be a ship in distress or posing as a ship of a friendly nationality and luring unsuspecting prey to her in that way. The targeted ships were usually caught by surprise (some did not even yet know that war had been declared), and their captain had to make the quick decision of whether to run, fight, or surrender. Since the captured ships were no match in speed, and usually had few or no arms, the unpleasant but expedient choice was to surrender. Kronprinz Wilhelm would send over a boarding party to search the captured vessel. If it appeared to have nothing of value or military significance, it was released and sent on its way. If it did have valuable (or contraband) cargo, or was a warship or a ship that might someday be converted to military use, the crew of Kronprinz Wilhelm would then systematically (and quite politely) transfer all of the crew, passengers, and their baggage and other valuable cargo from the captured ship to their own, including coal and other supplies. Then they would usually scuttle the captured vessel by opening up the seacocks (valves in the hull below the waterline), thereby causing the captured ship to fill with water after small charges were detonated, and sink. Throughout the entire journey, not a single life was lost.[24]

In this way she took the following:

- SS Highland Brae, United Kingdom

- Schooner Wilfred M., United Kingdom

- Barque Semantha, Norway

- Barque Anne de Bretagne, France

- SS Guadeloupe, France

- SS Tamar, United Kingdom

- SS Coleby, United Kingdom

- Schooner Pittan, Russia (released)

- SS Chasehill, United Kingdom

- SS Indian Prince, United Kingdom

- SS La Correntina, United Kingdom

- Four-mast Barque Union, France

- SS Bellevue, United Kingdom

- SS Mont Agel, France

- SS Hemisphere, United Kingdom

- SS Potaro, United Kingdom

She missed one potential success, when on 14 September 1914 she came across the British armed merchant cruiser RMS Carmania, already badly crippled following a battle with the German auxiliary cruiser SMS Cap Trafalgar, which had sunk shortly before Kronprinz Wilhelm's arrival. However, Kronprinz Wilhelm's commander chose to be cautious, and believing it to be a trap, steamed away without attacking the severely damaged Carmania.

Late in March 1915, the auxiliary cruiser headed north to rendezvous with another German supply ship at the equator. She arrived at the meeting point on the morning of 28 March and cruised in the neighborhood all day. That evening, she sighted a steamship in company with two British warships 20 mi (17 nmi; 32 km) distant. Though Kronprinz Wilhelm did not know it at the time, she had just witnessed the capture of her supply ship — Macedonia — by two British cruisers. The raider steamed around in the general vicinity for several days, but the passage of each succeeding day further diminished her hopes of a successful rendezvous.

1915–1917 internment

[edit]

Finally, a dwindling coal supply and an alarming increase in the sick list forced Kronprinz Wilhelm to make for the nearest neutral port. The apparent cause of the illness was malnutrition from their diet consisting mainly of beef, white bread, boiled potatoes, canned vegetables, and oleomargarine. The few fresh vegetables they seized from the captured vessels were reserved for the officers' mess.

Dr. Perrenon—the ship's surgeon—is reported to have said, "We had many cases of pneumonia, pleurisy and rheumatism among the men. They seemed to lose all resistance long before the epidemic broke out. We had superficial wounds, cuts, to deal with. They usually refused to heal for a long time. We had much hemorrhage. There were a number of accidents aboard, fractures, and dislocations. The broken bones were slow to mend." Slow healing is an early symptom of scurvy.

Early in the morning of 11 April 1915, she stopped off Cape Henry, Virginia, and took on a pilot. At 10:12 that morning, she dropped anchor off Newport News, and ended her cruise, during which she steamed 37,666 mi (32,731 nmi; 60,618 km) and destroyed just under 56000 tons of Allied shipping. She and her crew were interned, the ship was laid up at the Norfolk Navy Yard in Portsmouth, and her crew lived in a camp nearby, as "guests". In their internment, the crews of these vessels — numbering about 1,000 officers and men — built in the yard — from scrap materials — a typical German village named "Eitel Wilhelm", which attracted many visitors.

USS Von Steuben (1917–1919)

[edit]

On 6 April 1917, the United States declared war upon the German Empire. That same day, the Collector of the Port of Philadelphia seized the former German raider for the US on 22 May, President Woodrow Wilson issued the executive order which empowered the United States Navy to take possession of the ship and to begin to repair her. The internees became prisoners of war and were transferred to Fort McPherson, Georgia.

On 9 June, Kronprinz Wilhelm was renamed Von Steuben (ID-3017) in honor of Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, the German hero of the American Revolution, and commissioned in the United States Navy at Philadelphia.

The name Kronprinz Wilhelm was reclaimed by the German navy in 1918 when it renamed its battleship SMS Kronprinz as SMS Kronprinz Wilhelm. This ship was scuttled in June 1919 with the remainder of the High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow.

Career as a US ship

[edit]The newly named Von Steuben began her American Navy career as an auxiliary cruiser. Through the summer of 1917, her crew and workers at the Philadelphia Navy Yard prepared her to resume that role against her former masters. However, since the Allied and associated Powers already maintained virtual control of the seas, their need for that type of ship was minimal. Accordingly, on 21 September, the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations telegraphed an order to the Commandant, Philadelphia Navy Yard, to assign her to transport duty upon completion of repairs to meet a more pressing need—the transportation of troops and supplies to Europe. The ship completed preparations by 29 September and put to sea that same day for her first voyage. For the next four weeks, she remained close to American Eastern Seaboard, visiting Hampton Roads, Virginia and New York City in addition to Philadelphia.

On 31 October, she stood out of New York for her first transatlantic voyage under the American flag with 1,223 troops and passengers bound for Brest, France. At about 06:05 on the morning of 9 November, Von Steuben received some damage in a collision with the troop ship USS Agamemnon. Both ships lost men overboard, and a few received injuries. In addition, two of her 5 in (130 mm) guns and one of her 3 in (76 mm) guns were damaged. Though her bow was opened to the sea, Von Steuben maintained 12 kn (14 mph; 22 km/h) while the damage control party made repairs. The ship continued on with the convoy and arrived in Brest three days later. She disembarked passengers and unloaded cargo between 14 and 19 November, but she did not depart until 28 November.

Aftermath of the Halifax explosion

[edit]On her way back to the US, Von Steuben diverted to Halifax, Nova Scotia for coal. At about 09:14 on the morning of 6 December, she was about 40 mi (35 nmi; 64 km) from Halifax when the ship was rocked by a concussion so severe that many thought she had struck a mine or been torpedoed. Lookouts spied a great flame and a high column of smoke in the direction of the port where the French ammunition ship Mont-Blanc had exploded in Halifax Harbour. Von Steuben learned the facts when she entered the harbor at about 14:30 that afternoon. A portion of the city had been devastated by the explosion and the tsunami which followed causing the death of 2,000 in the Halifax Explosion (the largest man-made accidental explosion up to that time). The ship responded to the emergency by landing officers and men to patrol the city and assist in rescue efforts. The transport remained at Halifax until 10 December, and then continued her voyage back to Philadelphia where she arrived on 13 December.

Troop transport

[edit]After debarking her passengers, Von Steuben got underway from Philadelphia again on 15 December. She coaled at Newport News on 16 December and remained there until 20 December. On 20 December, Captain Yates Stirling Jr. assumed command of the transport from Commander Moses and she returned to sea, bound for Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where she disembarked marines. On 27 December, she got underway for the Panama Canal Zone. The ship transited the canal on 29 December and entered the drydock at Balboa, Panama that afternoon. Over the next three weeks, she received repairs of the damage to her bow. On 20 January 1918, the ship floated out of the dock and then retransited the canal. After coaling at Colón, Panama, she departed the Canal Zone and headed back to the east coast. From 28–31 January, Von Steuben stopped at Newport News where she took on two new 5-inch guns and a 3-inch gun to replace those damaged in the collision with Agamemnon. On 1 February, she returned to Philadelphia to resume duty transporting troops to France.

On 10 February, Von Steuben stood down the Delaware River with another convoy. She reached her destination, Brest, without incident on 24 February, unloaded her troops and cargo, and set out on the return voyage five days later. At about 16:20 on 5 March, a lookout spotted an object to port which resembled a submarine periscope. The alarm brought gun crews scurrying to their action stations, and they opened fire immediately. Before anyone realized that they were firing upon an innocuous piece of flotsam, a tragic accident occurred. The shell from one of her 5-inch guns exploded immediately upon leaving the barrel, and fragments struck three sailors. One died instantly, and the other two succumbed to their wounds later that night. Von Steuben coaled at Bermuda on 12–13 March and arrived at Norfolk on 16 March. After repairs and coaling, she moved on to Philadelphia to load troops and cargo for her third voyage to France.

Encounter with U-151

[edit]Her next two voyages to France and back were uneventful, as was the New York-to-Brest leg of the following one. However, on the return voyage, she encountered a U-boat. At about 12:30 on the afternoon of 18 June, one of her lookouts reported wreckage ahead. As she steamed closer, seven small boats under sail came into sight on the port bow about 5 mi (4.3 nmi; 8.0 km) away. Von Steuben began a zigzag approach to pick up what appeared to be boatloads of survivors from a sunken Allied ship. About 20 minutes later, her lookouts reported the wake of a torpedo approaching her bow from abaft the port beam. The gun crews manned their stations and began firing at the torpedo while Captain Stirling ordered the wheel hard to starboard and all engines full astern in an effort to avoid the torpedo. Meanwhile, some of the gunners had shifted their attention to what they thought to be the periscope of U-151, the source of the torpedo bearing down upon Von Steuben. The ship's efforts to slow down and turn away from the torpedo were successful. It passed a few yards ahead of the ship, and Von Steuben delivered a depth-charge barrage which subjected the submarine to a severe shaking. Stirling's evasive maneuver was considered unorthodox and conventional practice at the time would have been to attempt to outrun the torpedo. For his actions in saving the ship and the lives aboard, he was subsequently awarded the Navy Cross and the French Legion of Honor.

The real losers in that brief, but sharp, exchange were the survivors of the British steamship Dwinsk adrift in seven small boats. U-151 had sunk their ship earlier and remained in the area to use them as bait for other Allied ships such as Von Steuben. The possibility that they were simply decoys and that other submarines might be lurking about forced the ship to continue on without further investigation. That decision was further reinforced by the fact that the boats appeared empty. Credit for this must go to Dwinsk's master, who ordered his people to lie low in their craft so that other Allied ships would not be drawn into the waiting U-boat's trap. Fortunately, he and his men were saved eventually.

Von Steuben arrived in New York on 20 June and began preparations for another voyage to France. On 29 June, she embarked troops for passage to Europe, and the next day formed up with a convoy for the Atlantic crossing. At about noon on the third day out, a fire broke out in the forward cargo hold of USS Henderson. As the blaze grew in intensity, the transfer of the troops embarked became a necessary precaution, and Von Steuben approached the burning ship. Silhouetted by the flames, she would have made a perfect target for any U-boat in the vicinity, but she worked throughout the night and, by morning, had succeeded in embarking Henderson's more than 2,000 troops. Henderson came about and made it safely back to the US, while Von Steuben completed a somewhat cramped voyage at Brest on 9 July. Three days later, she headed back across the Atlantic with civilians and wounded soldiers returning to the US after service in Europe. After a peaceful voyage, the transport reached New York on 21 July.

After a short repair period in late July and early August, the ship resumed duty transporting troops to Europe. On 8 September 1918, Captain Yates Stirling Jr. transferred command to Captain Cyrus R. Miller. Between late August and the Armistice on 11 November, Von Steuben made three more round-trip voyages carrying troops to France and returning the sick and wounded to the US. Though all three were peaceful passages by wartime standards, they were not uneventful. On the return voyage from the first of the three, she weathered a severe hurricane in which three of her complement were washed overboard and lost at sea, while several others received injuries. On the New York-to-Brest leg of the second, the influenza epidemic of 1918 struck the 2,700 troops she had embarked and resulted in 400 stretcher cases and 34 deaths.

Von Steuben returned to New York from her ninth wartime voyage on 8 November. On 10 November, she began repairs at the Morse Dry Dock & Repair Company, Brooklyn, New York. The next day, Germany signed the armistice which ended hostilities. The former commerce raider completed repairs on 2 March 1919 and put to sea to begin bringing troops home from France. She continued to serve the Navy until 13 October 1919 when she was decommissioned and turned over to the United States Shipping Board (USSB).

1919–1923 commercial service

[edit]Although her name was struck from the Navy List on 14 October 1919, for almost five years the ship continued to serve the United States under the auspices of the USSB, first as Baron Von Steuben and after 1921 simply as Von Steuben again. Her name disappeared from mercantile records after 1923 and she was scrapped by Boston Iron & Metals Co.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schmalenbach, 1979, p, 48

- ^ Flamm, Oswald, ed. (1901). "'". Schiffbau, Schiffahrt und Hafenbau (in German) (2). Berlin: 509.

- ^ Norddeutscher Lloyd, Bremen, Jahrbuch, (year book) Verlag H.M. Hauschild, Bremen 1910, p. 64

- ^ Lloyd's Register, 1914, KRI–KRO.

- ^ "Express Steamship Kronprinz Wilhelm". Marine Engineering. November 1901. p. 451.

- ^ Berliner Tageblatt, Sunday 16 February 1902, p. 1

- ^ The Marconi Press Agency Ltd 1913, p. 239.

- ^ Schachner, Robert (1904). Das Tarifwesen in der Personenbeförderung der transozeanischen Dampfschiffahrt (in German). G Braun Verlag. p. 52.

- ^ E. und M. Elektrotechnik und Maschinenbau 20 Elektrotechnischer Verein Österreichs, Wien 1902. p. 117

- ^ The New York Times, 26 September 1901, p. 16

- ^ Ljungström, Henrik (23 March 2018). "Kronprinz Wilhelm". thegreatoceanliners.com. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ a b The New York Times, 24 December 1903, p. 3

- ^ a b The New York Times, 31 October 1907, p. 3

- ^ The New York Times, 14 April 1909, p. 11

- ^ The New York Times, 27 June 1909, p. C2

- ^ Thomas Kepler (2021). The Ile de France and the Golden Age of Transatlantic Travel. Lyons Press. pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b "The New Steamship "Kronprinz Wilhelm"". Harper's Weekly. Vol. 45. 1901. p. 1037.

- ^ a b "Express Steamship Kronprinz Wilhelm". Marine Engineering. November 1901. pp. 452–454.

- ^ "The "Kronprinz Wilhelm"". Scientific American Supplement. Vol. 53. 15 March 1902. p. 21,902. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "10-cent Steamship". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Karlsruhe – WW1 Naval Combat". Worldwar1.co.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ Putnam, William Lowell (2001). The Kaiser's merchant ships in World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 74. ISBN 0-7864-0923-1.

- ^ Gibson, RH (1918). Three Years of Naval Warfare. London: William Heinemann. p. 184. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Niezychowski, Alfred (1928). The Cruise of the Kronprinz Wilhelm. New York: Doubleday.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

Further reading

[edit]- Bonsor, NRP (1975) [1955]. North Atlantic Seaway. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-6401-7.

- Hoyt, Edwin Palmer (1974). Ghost of the Atlantic: the Kronprinz Wilhelm, 1914–19. London: Arthur Barker Ltd. ISBN 978-0213165116.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1914.

- The Marconi Press Agency Ltd (1913). The Year Book of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony. London: The St Katherine Press.

- Ruggles, Logan E; Norton, Owen W (1919). The Part the U.S.S. Von Steuben Played in the Great War. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Eagle Press. OCLC 10551594.

- Schmalenbach, Paul (1979). German raiders: A history of auxiliary cruisers of the German Navy, 1895–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-824-7.

External links

[edit]- NavSource gallery of Kronprinz Wilhelm and USS Von Steuben

- Several pictures and drawings of Kronprinz Wilhelm, at greatships.net

- Dokumentation „Kronprinz Wilhelm“ with Prince Henry (of Prussia) on Board Arriving in New York, filmed in 1902

- The Covington Sun (pdf), 15 April 1915 front page article about Kronprinz Wilhelm successfully reaching port after many of her crew had taken sick

- history.navy.mil: USS Von Steuben

- Page at US Navy's Historical Center

- Photos of the German Village constructed by the crew while interned in Virginia Archived 19 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- The Great Ocean Liners: Kronprinz Wilhelm

- Listing at MaritimeQuest.com

- 1901 ships

- Blue Riband holders

- Four funnel liners

- Kaiser-class ocean liners

- Maritime incidents in 1901

- Passenger ships of Germany

- Ships built in Stettin

- Ships of Norddeutscher Lloyd

- Steamships of the German Empire

- Auxiliary cruisers of the Imperial German Navy

- World War I commerce raiders

- World War I cruisers of Germany

- Captured ships

- Steamships of the United States Navy

- Transports of the United States Navy

- World War I transports of the United States