Royal necropolis of Ayaa

| Royal necropolis of Ayaa | |

|---|---|

Plan of the necropolis, showing Hypogea A and B in orange and brown, respectively | |

| Coordinates | 33°34′2.4″N 35°23′4.0″E / 33.567333°N 35.384444°E |

| Built for | Resting place of the Phoenician Sidonian royalty |

| Architectural style(s) | Phoenician |

| |

The royal necropolis of Ayaa (Arabic: قياعة, romanized: Qiyā'ah or Qiyâa;[a][1] also romanized as "Ayaʿa") was a group of two hypogea housing a total of 21 sarcophagi of kings and nobles of the city of Sidon (modern Saida), a coastal city in Lebanon, and a prominent Phoenician city-state. The sarcophagi were highly diverse in style, ranging across Egyptian, Greek, Lycian and Phoenician styles. The Phoenicians exhibited diverse mortuary practices that included inhumation and cremation. While written records about their beliefs in the afterlife are scarce, archaeological evidence suggests they believed in an afterlife known as the "House of Eternity." Burial sites in Iron Age Phoenicia, like the Ayaa necropolis, were typically located outside settlements, and featured various tomb types and burial practices.

The royal necropolis of Ayaa was located at the base of Hlaliyeh hill, at an elevation of 35 meters and approximately 500 meters from the sea, at the outskirts of the city of Sidon. The site had been previously surveyed by French orientalist and biblical scholar Ernest Renan who noted the presence of remnants of ancient ashlar masonry. The plot was owned by Mehmed Cherif Efendi, a Sidon local who was quarrying the land for construction material. The discovery of the necropolis in Ayaa was made in early 1877 by one of Cherif Efendi's workmen. The discovery is credited however to American Presbyterian minister William King Eddy who first learned of the necropolis from Cherif Effendi's workman. Eddy subsequently reported the discovery to the media and played a significant role in bringing attention to the site. The royal necropolis of Ayaa is the most famous of the royal necropoli of Achaemenid period Sidon; these consist of clusters of rock cut subterranean burial chambers accessible through vertical shafts.[2]

The discovery of the necropolis was a watershed moment for the career of Osman Hamdi Bey, the founding father of Ottoman archaeology and museology; it was his "most significant archaeological accomplishment", and firmly elevated his stature in the Western archaeological community. It was the reason for the construction of the main building of the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, which became known as the "Sarcophagus Museum". Even today the Ayaa sarcophagi are among the highlights of the museum, which remains by far the largest such museum in Turkey.[3][4]

The timing of the site's discovery was politically significant, as the Ottoman Empire had just begun to assert itself in the field of archaeology. The discovery of the Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II three decades before, and Renan's subsequent Mission de Phénicie, had excited the European scholarly community; under the new regime photographs of this discovery were made available to European scholars but the finds were to be kept in Istanbul – this was considered a "failure in European acquisition".[5]

Historical background

[edit]Phoenician funerary practices

[edit]The Phoenicians emerged as a distinct culture on the Levantine coast in the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550 – c. 1200 BC) as one of the successor cultures to the Canaanites.[6][7] They were organized into independent city-states that shared a common language, culture, and religious practices. They had, however, diverse mortuary practices, including inhumation and cremation.[8]

Scholars studying funerary practices in Iron Age Phoenicia (c. 1200 – c. 500 BC) note the absence of ancient texts describing beliefs about life after death and funeral rituals.[9] However, various finds provide information that Phoenicians, like other peoples of the ancient Near East, believed in life after death and the immortality of the soul. The afterlife was referred to as the "House of Eternity," and the dead were thought to continue living in the underworld.[10][9] Archaeological finds complement the limited written records; in Iron Age Phoenicia, burial sites were usually located outside settlements. Various types of tombs were found, such as earth pits, cist tombs, rock-cut tombs, some with shafts, and ashlar masonry-built tombs. In inhumation practices, the deceased was buried intact, laid directly on the floor, placed on a wooden plank or bench, or inside a coffin. The more affluent deceased was sometimes embalmed and wrapped in a shroud or clothed, and offerings like food and drink placed in pottery vessels, amulets, masks made of various materials, terracotta figurines were placed in the sepulture.[11] Funerals were accompanied by lamentations, as attested on the sarcophagus of the mourning women found in the Ayaa royal necropolis, and the Ahiram sarcophagus discovered in the royal necropolis of Byblos. Grief was expressed by crying, beating one’s chest, and tearing one’s clothes.[12]

Archaeological evidence of elite Achaemenid period burials abounds in the hinterland of Sidon. These include inhumations in underground vaults, rock-cut niches, and shaft and chamber tombs in Sarepta,[13] Ain al-Hilweh,[14] Ayaa,[15][16] Mgharet Abloun,[17] and the Temple of Eshmun.[18] Elite Phoenician burials were characterized by the use of sarcophagi, a consistent emphasis on the integrity of the tomb,[19][20] and evidence of mummification,[b] suggesting Egyptian influence on elite funerary customs.[25] Surviving mortuary inscriptions invoke deities to assist with the procurement of blessings, and to conjure curses and calamities on whoever desecrated the tomb.[26]

Hellenistic influence

[edit]Greek culture had a significant but lesser influence on Phoenician religion compared to Egyptian culture. Peaceful trade connections between the Phoenicians and Greeks began in the second millennium BC and continued to grow. Greek influence on Phoenician culture, including religion and art, became more pronounced from the 5th century BC, even while Phoenicia was under Persian rule. The Sidonian elite admired Greek art and architecture, as evident in the incorporation of Greek mythological scenes in their monuments. They also accepted the identification of their gods with Greek counterparts, such as Eshmun with Asclepius and/or Apollo and Melqart with Heracles. The Phoenician educated elite started learning Greek, delving into Greek mythology and philosophy.

Classical era Phoenician royal tombs in Sidon revealed the use of marble in the making of anthropoid sarcophagi imitating elite Egyptian basalt sarcophagi. These anthropoid sarcophagi gradually adopted increasingly realistic faces owing to Hellenistic influence.[12]

Excavation history

[edit]Previous discoveries in Sidon

[edit]Consecutive discoveries in the 19th century of necropoli in the hinterland of Sidon gave rare insight into the city's past. The remains of the ancient city were built over by a dense matrix of narrow medieval Souks and densely populated residential quarters. The first record of the discovery of an ancient necropolis in Sidon was made in 1816 by English explorer and Egyptologist William John Bankes.[27][28] Bankes, who was the guest of British adventurer and archaeologist Hester Stanhope, visited the vast necropolis that was accidentally discovered in 1814, in Wadi Abu Ghiyas at the foot of the towns of Bramieh and Hlaliye, northeast of Sidon. He sketched the layout of one of the sepulchral caves, made faithful watercolor copies of its frescoes, and removed two fresco panels which he sent to England.[c][28]

On 20 February 1855, Antoine-Aimé Peretié, the chancellor of the French consulate in Beirut and amateur archaeologist was informed by treasure hunter Alphonse Durighello, of an archaeological find in a hollowed-out rocky mound that was known to locals as Magharet Abloun 'The Cavern of Apollo'.[29][30][2][31] Durighello had taken advantage of the absence of laws governing archaeological excavation and the disposition of the finds under the Ottoman rule over Lebanon and had been involved in the lucrative business of digging up and trafficking archaeological artifacts. Under the Ottomans, it sufficed to either own the land or to have the owner's permission to excavate. Any finds resulting from the digs became the property of the finder.[32] To perform digs in the site of the cavern, Durighello bought the exclusive right from the land owner, the then Mufti of Sidon Mustapha Effendi.[32][33] Durighello, who is referred to as Peretié's "agent" in de Luynes' account, unearthed the Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II in an underground vaulted hypogeum and sold it to Peretié.[29][30][33][34]

Discovery and removal to Istanbul

[edit]At the beginning of 1887, Mehmed Cherif Effendi, the owner of a piece of land known as Ayaa, obtained a permit from the local authorities to exploit it as a quarry. One of Cherif Effendi's workmen uncovered a shaft and chamber tomb.[35][36] At nightfall, Cherif's workman made his way to American Presbyterian minister William King Eddy's home, a Sidon resident, to inform him of the find. The two men lowered themselves with a rope into the deep shaft, where Eddy realized upon inspecting the tomb that it was of considerable significance. He was the first to report this find to the media, and consequently, according to the American missionary narrative, is credited with the discovery.[36][37] Eddy had informed the English Orientalist William Wright who wrote an article in The Times imploring the British Museum to "take immediate measures to secure these treasures and prevent their falling into the hands of the vandal Turk".[37]

On 2 March 1887, Cherif reported to the Kaymakam of Sidon, Sadik Bey, of the shaft and chamber tomb. Sadik Bey examined the site and spotted through a hole in the eastern wall of the shaft two sarcophagi. He escalated the matter to the Vali of Syria, Rashid Nashid Pasha, and the Governor of Beirut Nassouhi Bey, and entrusted the well to the care of Essad Effendi from the gendarmerie of Sidon.[35]

Sadik Bey uncovered the entrance to two additional burial chambers to either side of the first one, both containing sarcophagi. Nachid Pacha was updated with the findings and had the work suspended due to the delicate nature of the finds until the arrival of Bechara Effendi, the chief engineer of the Vilayet of Syria. On March 15, Bechara Effendi arrived in Sidon and opened a total of seven burial chambers, all of which contained at least one sarcophagus. He wrote a summary report to the Ministry of Public Instruction in Istanbul, based on which, Sultan Abdul Hamid, tasked the new curator of the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, Osman Hamdi Bey with excavating the necropolis, and transporting valuables back to Istanbul.[38]

Hamdi Bey left Istanbul on 18 April 1887, accompanied by Demosthenes Baltazzi Bey the director of the archaeological service of the Vilayet of Aidin.[39] They arrived in Sidon 12 days later.[40][37] Hamdi Bey paid Mehmed Sherif Effendi, the owner of the land, 1500 Ottoman Liras at the behest of the Sultan.[39]

On 1 May 1887, Hamdy Bey initiated the excavations: He oversaw the construction of a ladder to retrieve sarcophagus fragments through the surface shaft and supervised the excavation of a sloping trench that began from the adjacent grove known as Bostan el-Maghara, and extended into one of the necropolis' subterranean vaults.[41] The trench was completed on the evening of 13 May.[42] He had the vaults closed off to deter curious locals and looters, had guards stationed on site, and built tramway tracks that provided easy access to the necropolis to facilitate the retrieval of the sarcophagi.[43] Once unearthed, he had a frigate brought from Istanbul and had the sarcophagi loaded onto it through openings cut in its side.[44]

A group of people rode from Beirut to visit the site and see the collection, and one sarcophagus was found to contain a well-preserved human body floating in a fluid.[44] During the transportation however, and while Hamdi Bey was at lunch, the workmen overturned the sarcophagus and poured the fluid out, such that, according to Jessup, the "secret of the wonderful fluid was again hidden in the Sidon sand". Notably, after the "peculiar fluid" left the sarcophagus, the body started to decompose.[44][45] Hamdy Bey noted in 1892 that he had kept a portion of the sludge that remained in the bottom of the sarcophagus.[46]

Bechara Effendi is credited with discovering new burial chambers and with devising transport mechanisms and superintending the transit of the massive troves to a frigate bound for Constantinople's museum.[47][48]

All tombs had been violated in antiquity[49] except for N17.[50] Hamdi Bey believed that all the interred were related. [49]

Commissioning of the Museum

[edit]On 17 August 1887, the Ottoman authorities announced that:

Because the solidity and weight of the antiquities recently found in Sidon makes their entrance into and their protection within the Imperial Museum impossible, [it has been decided that] there is a need for a new hall.[52]

French-Levantine architect Alexandre Vallaury, who an architecture scholar at Hamdi Bey’s School of Fine Arts who had previously designed the Yıldız Palace, was appointed to design the new building.[39] Construction began in 1888, was expanded to two-floors in 1889, and opened on 13 June 1891. The design of the museum included a number of architectural elements borrowed from the Ayaa sarcophagi. The Ottoman magazine Servet-i Fünun repeatedly described the new museum as having reached the level of the great museums of Western Europe.[53]

The new museum building housed the Ayaa sarcophagi alongside other sarcophagi and stelae that the museum had previously collected. The Ayaa sarcophagi was the museum’s “first large-scale and relatively complete archaeological collection from a single site”. The 1893 museum catalogue describes how each of the sarcophagi surpassed its equivalents, and that they provide and ability to visualize the development of such art forms over time though “an uninterrupted series from primitive Ionian art to Byzantine art”; the Tabnit sarcophagus showcased Egyptian funerary art, subsequently adapted into Phoenicians anthropoidal sarcophagi, both later supplanted by Greco-Roman style, such as the Sarcophagus of the Mourning Women and the Alexander Sarcophagus.[54][55]

Location

[edit]"On my return to Saida, I found that admirable necropolis from which were taken those magnificent sarcophagi which the Museum of Constantinople removed from Saïda three years ago, to have been annihilated! For the rock in which were these beautiful sepulchral vaults worthy of the archæologic marvels which they contained, the entire rock, had been brutally torn up and transformed into stupid masonry! And there, where reposed the ashes of King Tabnit, there is only an empty pit. That grandiose subterranean Museum, which earthquakes and the devastations of conquerors and centuries of barbarism had respected, has been effaced by the criminal stupidity of a miserable gardener of Saida.”

The ancient city of Sidon (modern Saida) is a port city located 45 km (28 mi) south of Beirut on the Eastern Mediterranean. The city fabric consists of medieval souks, which has hampered any attempt to excavate the underlying old city layers. The land where the necropolis was discovered sits at the bottom of the Hlaliyeh hill, at an altitude of 35 m (115 ft), and at a distance of 500 m (550 yd) from the sea. At the time of its discovery, it was bound on its east side by the aqueduct that supplied the city of Sidon with water, and on its north, west, and south sides by fruit tree groves. The large grove to the west of the site was known as Bostan el-Maghara (Arabic: بستان المغارة ; the Grove of the Cave).[57]

The Ayaa plot was roughly rectangular, measuring 100 m × 250 m (330 ft × 820 ft), and belonged to Mehmed Cherif Efendi, a Sidonian particular. It was barren and uncultivated, and contained remnants of an ancient ashlar wall that Ernest Renan took note of in his survey.[57]

Bostan el-Magara, also known as the "Garden of the caves," is located in Ayaa and is home to a number of underground hypogeums. The entrance to these hypogeums is located in a garden to the west of the excavation site and can be accessed by descending a few steps. These hypogeums were explored in 1888 and were found to contain tombs from the Christian period, as well as cippes and a marble head from the Roman period. The marble head was purchased by Joseph Durighello for 5 pounds.[1]

Three years after the extraction of the sarcophagi, the area was visited by Edmond Durighello, who noted that the tomb had not been protected and had been quarried for its rocks by local farmers.[58]

-

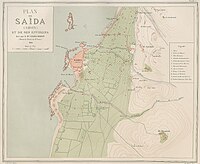

Sidon and Ayaa Necropolis (marked "1" in the top right corner)

-

Plan of Ayaa Necropolis

Description

[edit]

The underground chambers were accessible through a square vertical shaft that ended with a central vestibule. The four faces of the shaft were roughly aligned with the cardinal points and measured around 3.7 m (12 ft) each. The depth of the well, down to the vestibule floor, was 10.2 m (33 ft), including the 1 m (3.3 ft) meter deep soil layer. On the eastern wall of the well, at a depth of 6 meters, three rows of well-cut ashlar blocks were laid to prevent the collapse of the shaft. The vestibule opened on all four sides, at varying depths, into four different funerary vaults, to which Hamdi Bey assigned Roman numbers as they were being cleared: Vault I to the East, Vault II to the West, Vault IV to the South, Vault V to the North (see attached diagram).[50]

Vault I

[edit]On the eastern wall of the vestibule, lay the entrance to the first rock cut chamber dubbed Vault I by Hamdi Bey. Vault 1 had a low-ceiling measuring 1.8 m (5.9 ft) in height, and was accessible though a 1.7 m (5.6 ft) high and 1.6 m (5.2 ft) wide door. The entrance to this tomb had been walled shut, but the intruders had removed several masonry stone to enter. The vault measured 4.25 m × 3.35 m (13.9 ft × 11.0 ft), gradually widening towards the back to reach a width of 3.9 m (13 ft). Vault 1 contained three sarcophagi. Sarcophagus 1, named the "Sarcophagus of the mourning women", was made of white marble in the Ionic style. It was adorned with sculptures depicting mourning women. Sarcophagus 2, also made of white marble, was much smaller in size and devoid of any decoration.[59]

Both sarcophagi had been violated: Sarcophagus 1's lid was broken at the southwest corner and the lid of sarcophagus 2 had been raised, and held in place by a piece of a damaged decorative pilaster from Sarcophagus 1. Hamdi Bey observed looters had not suspected the presence of a third sarcophagus (dubbed Sarcophagus 17) in the same chamber. This latter was made of black basalt, and was of Egyptian origin; it was located beneath Sarcophagus 1 and was discovered later during the clearing of the hypogeum.[59]

Vaults II and III

[edit]Facing this first tomb, on the western wall of the well, there was a second chamber (Vault II), measuring 3.6 m × 3.4 m (12 ft × 11 ft). This tomb's entrance was also walled up, and breached by looters. The height of the Vault II was 2 m (6.6 ft). In the middle of the vault, a rectangular pit was excavated, measuring 1.5 m × 3 m (4.9 ft × 9.8 ft), and 2.35 m (7.7 ft) deep. At the bottom of this first pit, lay another smaller rectangular pit, measuring 0.6 m × 1.1 m (2.0 ft × 3.6 ft), and 0.35 m (1.1 ft), and was filled with human bones.[60] North of these pits, a very small originally sealed rock cut niche was found, barely accommodating a white marble anthropoid sarcophagus (Sarcophagus 3) that was also looted. This niche measured 2.35 m × 1.2 m (7.7 ft × 3.9 ft), and had a height of 1.2 m (3.9 ft). The large pit leading to this small tomb had initially been filled with soil, over which a regular layer of rectangular stones was placed to level tomb II.[59]

The south of Vault II, gave access to a third chamber (Vault III) through a 2.4 m (7.9 ft) wide door. This vault was the finest, and the largest, measuring 6.1 m (20 ft) in width at the entrance and narrowing to 6 m (20 ft) at the rear. Its length was 6.4 m (21 ft), and the ceiling height was 2.75 m (9.0 ft). A small groove was carved into the floor surrounding the walls to collect seepage water. On the walls, a horizontal red line was visible, indicating symmetrically spaced rectangular openings. These openings were likely meant for accommodating large beams horizontally placed across the tomb, possibly to secure the sarcophagus lids using ropes. Like all the other tombs, the original entrance had been walled up, but the entrance of this specific tomb displayed more intricate craftsmanship. Two massive, finely cut stone blocks, measuring 1.75 m × 0.55 m (5.7 ft × 1.8 ft) served as architraves. This tomb housed four sarcophagi (Sarcophagus 4, 5, 6, and 7), all looted. The largest and finest among them was Sarcophagus 7 (the Alexander Sarcophagus), adorned with exceptional bas-reliefs that impressively retained their polychrome paint. The three others, of the same shape as the Alexander Sarcophagus, were almost identical but were simple and lacked any sculpted figures on their troughs.[61]

Vault IV

[edit]

The south wall of the vestibule opens to Vault IV which was carved 2 m (6.6 ft) lower than the previous chambers and contained two sarcophagi. Vault IV was 3.5 m (11 ft) high, and measured 4 m (13 ft) wide at the entrance, widening to 4.5 m (15 ft) at its far end. The entrance to this chamber was 2.9 m (9.5 ft) high and 2.1 m (6.9 ft) wide. The first sarcophagus (Sarcophagus 8) was carved from black basaltic rock and of simple design. Sarcophagus 9, dubbed the Lycian sarcophagus was made of Parian marble.[62]

Vaults V, VI and VII

[edit]

The north wall of the vestibule opens to Vault V, which itself served as a vestibule leading to vaults VI and VII . Vault V measured 2 m × 3 m (6.6 ft × 9.8 ft) and was carved 2.1 m (6.9 ft) below the level of the main vestibule. Its North wall housed a niche, carved at a height of 1.8 m (5.9 ft). This niche was 1.2 m (3.9 ft) deep, 2.7 m (8.9 ft) wide, and 1.6 m (5.2 ft) high. The niche housed Sarcophagus 10, crafted from plain limestone and featuring a simple design, which was also looted. An intact alabaster vase was found next to this sarcophagus.[63]

Vault VI was accessible through a door on the west wall of Vault V. It measured 4.7 m × 4.4 m (15 ft × 14 ft) and had a height of 2.7 m (8.9 ft). Inside, there were four sarcophagi, all made of white marble and labeled as Hamdy Bey Sarcophagus 13, 14, 15, and 16. Among them, Sarcophagus 16, known as the Sarcophagus of the Satrap, was adorned with sculptures, while the other three had a simple yet elegant design. All the sarcophagi from this vault were looted.[64]

Vault VII, which opens to the east of Vault V, is the smallest of all. It measures 3.2 m (10 ft) in length and 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in width, with a ceiling height of only 1.8 m (5.9 ft). Like the previous vaults, this vault was walled up. It contained two looted sarcophagi (sarcophagi 11 and 12); Sarcophagus 11, is an anthropoid sarcophagus made of white marble. The other, simple in design, is also made of white marble, is similar in shape to sarcophagi 2, 10, and 14.[65]

Finds

[edit]| Vault | Sarcoph. | Image | Sarcophagus description | Vault contents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | #1 (Mourning women) |

|

Hellenic style sarcophagus, shaped like an Ionic temple and made of Pentelic marble with polychrome reliefs.[66] The trough stands on a 0.4 m (1.3 ft) pedestal consisting, from bottom to top, of a flat band, a row of egg-and-dart motifs framing an intricate relief depicting a hunting scene, a molding and a final flat band that serves as a plinth. On top of the plinth, a row of 14 Ionic columns and four pilasters enshrine 18 female figures in mourning.[67] The columns are surmounted by an architrave. The trough measures 2.68 m × 1.38 m (8.8 ft × 4.5 ft) and 1.29 m (4.2 ft) high.[67]

The lid measures 2.87 m × 1.56 m (9.4 ft × 5.1 ft) and 0.4 m (1.3 ft) high. It features a relief of a funerary procession, pediments, sphinxes, acrtoteria, and nine downspouts in the shape of lion heads.[68] Traces of polychromic paint were still found on parts of the sarcophagus lid and trough.[69] Dimensions according to Hitzl: Trough 2.659 m × 1.385 m (8.72 ft × 4.54 ft) and 1.28 m (4.2 ft) Lid dimensions: 2.789 m × 1.497 m (9.15 ft × 4.91 ft) and 50 cm (20 in) high lid.[70] |

Sarcophagus 1: Human remains and the skulls of seven greyhounds and a bronze buckle. [71] Sarcophagus 2 human remains only. [69] |

| #2 |

|

Theca type made of plain white marble. It had been violated and contained only a few bones. Hamdy Bey decided to leave it in-situ, regretting later his decision.[69] | ||

| I (beneath) | #17 (Amoashtart) |

|

Black stone in Egyptian style. | |

| II | #3 |

|

White marble anthropoid containing human bones.[72] | Sarcophagus 3: violated, containing only human bones. There was also a plank of sycamore, shaped to fit the bottom of the trough. This plank had fourteen symmetrical holes drilled along its length on each side. It measures 1.9 m (6.2 ft) in length and its width at the top end was 26 cm (10 in), tapering down to 22 cm (8.7 in) and at the foot end.[72]

The pit in the same Vault II; it was completely filled with bones, among which no objects were found.[72] |

| III | #4 |

|

Pentelic marble, shaped like a Greek temple. Dimensions: 2.62 m × 1.38 m (8.6 ft × 4.5 ft) and 1.15 m (3.8 ft). Undecorated trough faces. Inscribed with the Phoenician letter 𐤀.[73] | Small Terracotta head in the trench and a silver medal, a seated terracotta figurine missing its head.[74] |

| #5 |

|

Pentelic marble, shaped like a Greek temple. Dimensions: 2.64 m × 1.42 m (8.7 ft × 4.7 ft) and 1.12 m (3.7 ft). Undecorated trough faces. Inscribed with the Phoenician letter 𐤁.[73] | ||

| #6 |

|

Pentelic marble, shaped like a Greek temple. Dimensions: 2.80 m × 1.20 m (9.2 ft × 3.9 ft) and 1.13 m (3.7 ft). Undecorated trough faces.[73] | ||

| #7 (Alexander) |

|

Pentelic marble. Trough Dimensions 3.02 m × 1.51 m (9.9 ft × 5.0 ft) and 1.26 m (4.1 ft) high. [75]Lid dimensions: 3.05 m × 1.55 m (10.0 ft × 5.1 ft) and 0.69 m (2.3 ft) high. [75] | ||

| IV | #8 |

|

Massive and heavy black basalt sarcophagus, left in-situ, because according to Handy Bey "Not only was it extremely heavy, but it also lacked any sculptural ornamentation."[76] Dimensions: 2.6 m × 1.2 m (8.5 ft × 3.9 ft) and 1.26 m (4.1 ft) high. The walls of the sarcophagus were 32 cm (13 in) wide causing it to be super heavy. Contained decomposed bones and remains of a skull. [77] | Four Parian marble decorative elements that Hamdy Bey believed acted as support for a small sarcophagys.[78] Sizes 9x12cm. |

| #9 (Lycian) |

|

Found extensively damaged. [76] It is made of Parian marble, and resembles the shapes of ogival Lycian tombs, such as the Tomb of Payava, hence its name. The sarcophagus is decorated with reliefs, the side reliefs illustrating a lion-hunt and a boar-hunt, while the reliefs at the end show fighting centaurs and sphinxes.[79] Trough: 2.37 m × 1.195 m (7.78 ft × 3.92 ft) and 1.34 m (4.4 ft) high. Lid 2.425 m × 1.265 m (7.96 ft × 4.15 ft) and 1.625 m (5.33 ft) high. [80] | ||

| V | #10 | Simple stone sarcophagus, equivalent to number 2 | Nothing [81] | |

| VI | #13 |

|

Simple marble | Bronze bowl.[81] terracotta and alabaster vases and receptacles.[81] |

| #14 | Simple theca, similar to numbers 2, 10 and 12 | |||

| #15 |

|

Simple marble | ||

| #16 (Satrap) |

|

Sarcophagus in the shape of a Greek temple, made of Parian marble. It measures 2.88 m × 1.18 m (9.4 ft × 3.9 ft), and 1.44 m (4.72 ft) in height. It still held traces of blue paint.

The base of the trough is adorned with a row of heart-shaped motifs, while the top features rows of pearls and ovoid elements. Four sculpted panels, framed by a band of palmettes, adorn the faces of the sarcophagus. They represent scenes of a banquet, a journey and a lion hunt.[82] | ||

| VII | #11 |

|

Marble anthropoid, female figure | Nothing [81] But in Sarcophagus 11 trough contained 29 necklace beads made of gold and silver, 3 carnelian wedjat eye amulets, and 6 glass beads.[81] A large deposit of mercury drops at the bottom of the sarcophagus trough.[81] |

| #12 | White marble simple theca, similar to numbers 2, 10 and 14 [81]

Contained human remains. Not of interest and left in situ.[81] Dimensions: 2.2 m × 0.8 m (7.2 ft × 2.6 ft) height not documented.[81] | |||

| Hypogeum B | Tabnit |

|

Inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs and Phoenician writing |

See also

[edit]- Royal necropolis of Byblos – Phoenician necropolis in Lebanon

- Tyre Necropolis – Lebanese UNESCO World Heritage site

Notes

[edit]- ^ The name was transliterated in the vernacular by Western and Ottoman scholars, as unlike Modern Standard Arabic, Levantine Arabic does not pronounce "ق" as a "q" but rather as a glottal stop. In Arabic, the place name is alternatively spelled Arabic: قياع.

- ^ Sidonian elite mummies include the mummy of Sidonian King Tabnit, discovered by Hamdy Bey at Ayaa,[21] and the well-preserved mummy of a young girl found by Ottoman archaeologist Theodore Makridi in the Sidonian locality of Dahr el Aouq in 1898. The mummy of the young girl showed similar embalming and funerary dispositions to the mummy of Tabnit. The young girl mummy was fastened to a sycamore timber, and buried in a theca (undecorated marble sarcophagus) in a shaft and chamber tomb.[22] A final, more recently excavated royal tomb in Sidon contained a mummy wrapped in linen cloth.[23][24]

- ^ Now in the National Trust and County Record Office in Dorchester

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 2.

- ^ a b Caubet & Prévotat 2013.

- ^ Dinler 2018, p. 735: "Osman Hamdi Bey's most significant archaeological accomplishment can be considered as the Sidon excavations... Even today, these sarcophagi contribute to the highlights of the Istanbul Archaeology Museum... With the success of the Sidon excavations, Osman Hamdi Bey gained fame and his place among the global archaeology world..."

- ^ Keskin 2023.

- ^ Shaw 2003, p. 145-146, 156-157.

- ^ Motta 2015, p. 5.

- ^ Jigoulov 2016, p. 150.

- ^ Jigoulov 2016, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b Sader 2019, p. 216.

- ^ Bonnet & Niehr 2010, p. 117.

- ^ Sader 2019, pp. 216–234.

- ^ a b Sader 2019, p. 234.

- ^ Saidah 1983.

- ^ Torrey 1919.

- ^ Renan 1864, p. 362.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a.

- ^ Luynes 1856.

- ^ Macridy 1904a.

- ^ Gras, Rouillard & Teixidor 1991, p. 127.

- ^ Ward 1994, p. 316.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, pp. 86–143.

- ^ Macridy 1904b, pp. 556–560.

- ^ Ghadban 1998, p. 147.

- ^ Sader 2019, p. 229.

- ^ Sader 2019, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Luynes 1856, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Lewis, Sartre-Fauriat & Sartre 1996, p. 61.

- ^ a b Jidéjian 2000, p. 15–16.

- ^ a b Luynes 1856, p. 1.

- ^ a b Jidéjian 2000, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Klat 2002, p. 101.

- ^ a b Klat 2002, p. 102.

- ^ a b Tahan 2017, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Renan 1864, p. 402.

- ^ a b Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. I.

- ^ a b Jidéjian 2000, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Jessup 1910, p. 506–507: "On the 14th of March a letter came from Mr. Eddy of a wonderful discovery in Sidon of ancient tombs, containing some white polished marble sarcophagi of exquisite beauty and marvellous sculpture. Mr. Eddy had been into the tombs hewn in the solid rock thirty feet below the surface and had measured and described all the sarcophagi of white and black marble with scientific exactness. On the 21st Dr. Eddy received from his son an elaborate report on the discovery which was intended to be sent to his brother Dr. Condit Eddy in New Rochelle. I obtained permission to make a copy for transmission to Dr. William Wright of London, and sent it by mail the next day. Dr. Wright sent it to the London Times with a note in which he expressed the hope that the authorities of the British Museum would "take immediate measures to secure these treasures and prevent their falling into the hands of the vandal Turk". The Times reached Constantinople. Now it happened that the department of antiquities at that time as now was under the charge of Hamdi Beg, a man educated in Paris, an artist, an engineer, and well up in archaeology. When he saw that article of Mr. Eddy's in the Times and Dr. Wright's letter, he said to himself (as he afterwards told us), "I'll show what the 'Vandal Turk' can do!"

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. II.

- ^ a b c Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. III.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, pp. III, 3.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 13.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 21.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c Jessup 1910, p. 507: "One sarcophagus, when the lid was opened, contained a human body floating in perfect preservation in a peculiar fluid. The flesh was soft and perfect in form and colour. But, alas, while Hamdi Beg was at lunch, the over-officious Arab workmen overturned it and spilled all the precious fluid on the sand. The beg's indignation knew no bounds, but it was too late and the body could not be preserved, and the secret of the wonderful fluid was again hidden in the Sidon sand."

- ^ Gubel 2003, p. 98–100.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, pp. 101–103:"Alors seulement nous pûmes enfin voir l'intérieur du sarcophage. Une couche de sable jaunâtre et humide de laquelle émergeaient la face décharnée, les clavicules, les rotules, ainsi que le bout des pieds auxquels manquaient les doigts, remplissait le fond de la cuve jusqu'à 25 centimètres de ses bords... Débarrassé du couvercle, je fis d'abord tirer de la cuve le corps du roi et j'ordonnai de l'étendre sur une planche pour l'emporter dehors et le confier au docteur Mourad Effendi, médecin municipal de Saïda, que j'avais chargé de le mettre en état d'être transporté à constantinople; car tous les muscles des parties postérieures ainsi que tous les organes internes du thorax et de l'abdomen étaient parfaitement conservés. Apres avoir fait vider la cuve, je conservai une portion de la boue formée de sable et de pourriture qu'elle contenait, et je fis passer le reste à travers un crible quand cette boue eut été, au préalable, délayée dans l'eau. Rien n'y a été trouvé, si ce n'est quelques fragments d'anneaux en argent."

- ^ Palestine Exploration Fund — Quarterly statement for 1887. London: Palestine Exploration Fund Society Office. 1887. pp. 201–212.

- ^ Osman Hamdi Bey; Reinach, Theodor (1892). Une nécropole royale à Sidon (in French). Paris: Ernest Leroux.

- ^ a b Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 4.

- ^ a b Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 6.

- ^ Shaw 2003, p. 157: "The use of sculptures as punctuation between windows and columns on the building, the inset Ionian columns along the exterior, and the fanned cornice on the edge of the roof suggest that the plan was probably based on the temple design of one of the sarcophagi in the collection, the Sarcophagus of the Wailing Women… By using a sarcophagus found in the empire as the model for the museum, however, the architectural style repositioned this heritage as part of the local, drew attention to the shared roots of Ottomans and Europeans, and visualized the inclusion of the Ottoman Empire in Western Civilization as an empirical, archaeologically proven fact."

- ^ Shaw 2003, p. 157, IBA MV 23:34/ 1304.Za.27 = August 17, 1887Quoted from the Istanbul Prime Minister’s Archives/Basbakanlik Arsivi (IBA)

- ^ Shaw 2003, p. 156-159.

- ^ Joubin 1893, p. IX: "Ces monuments, d'époques et de provenances très variées, fourniraient les éléments d'une histoire complète de la sculpture funéraire chez les anciens. La classe des sarcophages est de beaucoup la plus importante. Historiquement, ces monuments forment une série ininterrompue depuis l'art ionien primitif jusqu'à l'art byzantin.”

- ^ Shaw 2003, p. 159.

- ^ Frothingham, A. L. (1890). "Archæological News". The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts. 6 (1/2). Archaeological Institute of America: 186. doi:10.2307/496182. ISSN 1540-5079. JSTOR 496182. S2CID 245267816.

- ^ a b Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 1.

- ^ Jidéjian 2000, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 7.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, pp. 7, 15.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 8.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 10.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 11.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, pp. 12.

- ^ Reinach 1892, pp. 178–179.

- ^ a b Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 28.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, pp. 25–29.

- ^ a b c Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 29.

- ^ Hitzl 1991, p. 179.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Joubin 1893, p. 42–44.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 16.

- ^ a b Hitzl 1991, p. 181.

- ^ a b Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 30.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 33.

- ^ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 35.

- ^ Freely & Glyn 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Hitzl 1991, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892a, p. 17.

- ^ Joubin 1893, p. 23–25.

Primary sources

[edit]- Hamdy Bey, Osman; Reinach, Théodore (1892a). Une nécropole royale à Sidon : fouilles de Hamdy Bey. Texte [A royal necropolis in Sidon: excavations of Hamdy Bey. Plates] (in French). Paris: Ernest Leroux. doi:10.11588/DIGLIT.5197.

- Hamdy Bey, Osman; Reinach, Théodore (1892b). Une nécropole royale à Sidon : fouilles de Hamdy Bey. Planches [A royal necropolis in Sidon: excavations of Hamdy Bey. Plates] (in French). Paris: Ernest Leroux. doi:10.11588/DIGLIT.5198.

- Reinach, Théodore (1892). "Les sarcophages de Sidon au Musée de Constantinople" [Sidon sarcophagi at the Museum of Constantinople]. Gazette des Beaux-Arts (in French). J. Claye: 177 ff.

- Joubin, André [in French] (1893). Catalogue sommaire [des] monuments funéraires [du] Musée Imperial Ottoman [Summary catalog of funerary monuments in the Imperial Ottoman Museum] (in French). Constantinople: Mihran imprimeur. OCLC 25995133.

- Mendel, Gustave [in French] (1912). Musées Impériaux Ottomans. Catalogue des sculptures grecques, romaines et byzantines [Imperial Ottoman Museums. Catalog of Greek, Roman and Byzantine sculptures] (in French). Constantinople: Musée Impérial. OCLC 907607793.

Secondary sources

[edit]- Caubet, Annie (1999). "Remarques sur les Fouilles du Dr. Georges Contenau a Helalieh et Ayaa (Sidon)" [Notes on the excavations of Dr. Georges Contenau in Helalieh and Ayaa (Sidon)] (PDF). National Museum News (in French) (10): 9–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2023.

- Bonnet, Corinne; Niehr, Herbert (2010). Frevel, Christian; Zenger, Erich (eds.). Religionen in der Umwelt des Alten Testaments II: Phönizier, Punier, Aramäer: Phonizier, Punier, Aramaer [Religions in the Environment of the Old Testament II: Phoenicians, Punic, Aramaeans: Phoenicians, Punic, Aramaeans] (in German). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. ISBN 9783170130463. OCLC 699246706.

- Caubet, Annie; Prévotat, Arnaud (2013). "Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, king of Sidon". Louvre Museum. Musée du Louvre. Archived from the original on 2021-02-10. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- Çelik, Zeynep (2016). About Antiquities: Politics of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9781477310618. OCLC 962063790.

- Contenau, Georges (1920). "Mission archéologique à Sidon (1914)". Syria (in French). 1 (1). Paris: Librairie Paul Geuthner: 16–55. doi:10.3406/syria.1920.2837. hdl:2027/wu.89096174727. ISSN 0039-7946. OCLC 261344575 – via Persée.

- Dinler, Mesut (2018). "The Knife's Edge of the Present: Archaeology in Turkey from the Nineteenth Century to the 1940s". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 22 (4). Springer: 728–745. doi:10.1007/s10761-017-0446-x. ISSN 1092-7697. JSTOR 45154561. OCLC 44169294. S2CID 254538197. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- Freely, John; Glyn, Anthony (2000). The Companion Guide to Istanbul and Around the Marmara. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Companion Guides. ISBN 9781900639316. OCLC 42003538.

- Ghadban, Ch. (1998). "La nécropole d'époque perse de Magharat Tabloun à Sidon" [The Persian necropolis of Magharat Tabloun in Sidon]. Liban: l'autre rive : exposition présentée à l'Institut du monde arabe du 27 octobre au 2 mai 1999 [Lebanon: the other shore: exhibition presented at the Institut du monde arabe from October 27 to May 2, 1999] (in French). Paris: Institut du monde arabe, Flammarion. ISBN 9782843060199. OCLC 421710063.

- Gras, Michel; Rouillard, Pierre; Teixidor, Javier (1991). The Phoenicians and Death. Beirut: Faculty of Arts and Sciences, American University of Beirut. OCLC 708392245.

- Gubel, Eric J. K. (2003). "Review of Phönizische Anthropoide Sarkophage". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (332): 98–100. doi:10.2307/1357812. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 1357812.

- Hitzl, Ingrid (1991). Die griechischen Sarkophage der archaischen und klassischen Zeit [The Greek sarcophagi of the archaic and classical period]. Studies in Mediterranean archaeology and literature (in German). Partille: P. Åströms. ISBN 9789170810428. OCLC 906588033.

- [Jessup, Henry Harris (1910), Fifty-Three Years In Syria, vol. 2, Fleming H. Revell Company, p. 507

- Jidéjian, Nina (2000). "Greater Sidon and its "Cities of the Dead"" (PDF). National Museum News: 15–24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2023.

- Jigoulov, Vadim S. (2016). The Social History of Achaemenid Phoenicia: Being a Phoenician, Negotiating Empires. Bible World. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 9781134938162.

- Keskin, Buse (12 July 2023). "Istanbul Archaeological Museums illuminate rich history, cultural legacy". Daily Sabah. Archived from the original on 21 August 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- Klat, Michel G. (2002). "The Durighello Family" (PDF). Archaeology & History in Lebanon (16). London: Lebanese British Friends of the National Museum: 98–108. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-11.

- Lewis, Norman Nicholson; Sartre-Fauriat, Annie; Sartre, Maurice (1996). "William John Bankes.Travaux en Syrie d'un voyageur oublié" [William John Bankes. The works in Syria of a forgotten traveler]. Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire. 73 (1): 57–95. doi:10.3406/syria.1996.7502. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023.

- Luynes, Honoré Théodoric Paul Joseph d'Albert duc de (1856). Mémoire sur le sarcophage et inscription funéraire d'Esmunazar, Roi de Sidon [Memoire on the sarcophagus and funeral inscription of Esmunazar, King of Sidon]. Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum (in French). Henri Plon. Archived from the original on 2020-10-27. Retrieved 2021-01-22 – via Bayerische Staatsbibliothek.

- Macridy, Theodor (1904a). Le temple d'Echmoun à Sidon: fouilles du Musée impérial ottoman [The temple of Eshmun in Sidon: excavations of the Ottoman Imperial Museum] (in French). Paris: Librairie Victor Lecoffre. OCLC 6998289.

- Macridy, Théodore (1904b). "A travers les nécropoles Sidoniennes" [Through the Sidonian necropoli]. Revue Biblique (1892-1940). 1 (4): 547–572. ISSN 1240-3032. JSTOR 44102400 – via JSTOR.

- Merril, Selah (1888). "Account of a royal necropolis discovered at Saida by Hamdi Bey". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 20 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1179/peq.1888.20.1.9. ISSN 0031-0328. OCLC 5525866380.

- Motta, Rosa Maria (2015). Material culture and cultural identity: A study of Greek and Roman coins from Dora. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781784910938.

- Renan, Ernest (1864). Mission de Phénicie - Dirigée par M. Ernest Renan - Texte [Mission of Phoenicia] (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Imprimerie impériale.

- Sader, Hélène (2019). The History and Archaeology of Phoenicia. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9780884144069. OCLC 1338058995.

- Saidah, Roger (1983). Nouveaux éléments de datation de la céramique de l'Age du Fer au Levant. Atti del I Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici Libreria della SpadaLibri esauriti antichi e moderni Libri rari e di pregio da tutto il mondo. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023.

- Shaw, Wendy M.K. (2003). Possessors and Possessed: Museums, Archaeology, and the Visualization of History in the Late Ottoman Empire. University of California Press. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520233355. OCLC 52998857.

- Tahan, Lina G. (2017). "Trafficked Lebanese Antiquities: Can They Be Repatriated from European Museums?". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies. 5 (1): 27–35. doi:10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.5.1.0027. ISSN 2166-3556. JSTOR 10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.5.1.0027. S2CID 164865577.

- Torrey, Charles C. (1919). "A Phoenician Necropolis at Sidon". The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research in Jerusalem. 1: 1–27. doi:10.2307/3768461. ISSN 1933-2505. JSTOR 3768461. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023.

- Ward, William A. (1994). "Archaeology in Lebanon in the Twentieth Century". The Biblical Archaeologist. 57 (2): 66–85. doi:10.2307/3210385. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210385. S2CID 163213202. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023.