Ross procedure

| Ross procedure | |

|---|---|

Ross Procedure | |

| Other names | Pulmonary autograft, switch procedure, double-switch Ross procedure |

| Specialty | Cardiac surgery |

| Uses | Aortic valve disease[1] |

| Approach | Median sternotomy[1] |

| Types | Subcoronary method, root replacement technique[2] |

| Outcomes | Good if performed in specialist centre,[1] 80% to 90% 10 year survival.[3] |

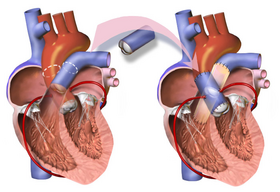

The Ross procedure, also known as pulmonary autograft, is a heart valve replacement operation to treat severe aortic valve disease, such as in children and young adults with a bicuspid aortic valve.[1] It involves removing the diseased aortic valve, situated at the exit of the left side of the heart (where the aorta begins), and replacing it with the person's own healthy pulmonary valve (autograft), removed from the exit of the heart's right side (where the pulmonary artery begins).[4] To reconstruct the right-sided exit, a pulmonary valve from a cadaver (homograft), or a stentless xenograft, is used to replace the removed pulmonary valve.[1][a] Compared to a mechanical valve replacement, it avoids the requirement for thinning the blood, has favourable blood flow dynamics, allows growth of the valve with growth of the child and has less risk of endocarditis.[1]

It is not performed if Marfan syndrome, pulmonary valve disease, or immune problems like lupus are present.[3] Other contraindications include severe coronary artery disease and severe mitral valve disease.[3] Due to a higher chance of dysfunction of the autograft, it may not always be safe to perform in rheumatic valve disease, or if a dysplastic dilated aortic root is present.[6] Complications include endocarditis, degeneration of the valves, aortic dissection, haemorrhage and venous thromboembolism, among others.[1][2] It risks having a disease of two valves instead of one.[7]

The procedure requires technical expertise.[4] It can be performed using the traditional subcoronary method or more commonly the root replacement technique, which requires re-implanting the coronary arteries.[8][9]

After the operation, good blood pressure control prevents early dilatation of the new aortic root and allows the pulmonary autograft, now in the aortic position, to settle in its new environment.[10] It may need reoperating on at a later date.[7] Complications occur in 3 to 5% of cases, with early death rate almost negligible in very experienced centres.[3] 80% to 90% of cases survive 10 years.[3] As of 2014, the Ross procedure comprises less than 1% of all aortic valve replacements in North America.[1]

The procedure was first performed using the subcoronary method in 1967 by Donald Ross, for whom the procedure is named.[8][11] The root replacement method was introduced in the early 1970s.[8] It was continued and modified by others such as Magdi Yacoub, who used fresh valves from the explanted hearts of transplant recipients.[11]

Uses

[edit]

Several adaptations of the Ross procedure have evolved, but the principle is essentially the same; to replace a diseased aortic valve with the person's own pulmonary valve (autograft), and replace the person's own pulmonary valve with a pulmonary valve from a cadaver (homograft) or a stentless xenograft.[1][4] It is an alternative to a mechanical valve replacement, particularly in children and young adults.[7] It avoids the need for thinning the blood, has favourable blood flow dynamics and the valve grows as the person grows.[7]

The most common reason for performing the Ross procedure in children and young adults is for bicuspid aortic valve.[1]

Contra-indications

[edit]It is not performed in Marfan syndrome, if pulmonary valve disease, or if immune problems like lupus.[3] Other contraindications include severe coronary artery disease and severe mitral valve disease.[3] Due to a higher chance of dysfunction of the autograft, it may not always be safe to perform in rheumatic valve disease, or if a dysplastic dilated aortic root.[6]

Risks/complications

[edit]The procedure requires technical expertise, and risks converting a single-valve disease into double-valve disease.[4] It may need re-operating on at a later date.[7] Complications include endocarditis, degeneration of the valves, aortic dissection, haemorrhage and venous thromboembolism, among others.[1][2]

Technique

[edit]Before the operation, preparations include transthoracic echocardiography and measurements of the ascending aorta and the pulmonary valve.[10] Under general anaesthesia, the chest is cut open in the midline.[3] The heart and aorta are exposed before the heart is temporarily stopped and its function taken over cardiopulmonary bypass.[3] Subsequent steps include removing the diseased aortic valve and mobilizing the coronary arteries, followed by harvesting and preparing the person's own healthy pulmonary valve, before implanting it within the left ventricular outflow tract, the exit of the left side of the heart (where the aorta begins).[1][10] Then the coronary arteries are reimplanted, before the pulmonary homograft is implanted in the right ventricular outflow tract, the exit of the heart's right side (where the pulmonary artery begins).[1][10] The pulmonary autograft is joined to the ascending aorta.[1][10]

Pulmonary valve replacement

[edit]Cryopreserved pulmonary homografts were most often used for a long time until the introduction of decellularized homografts.[2]

Variations

[edit]If the left sided outflow root needs to be enlarged to fit the pulmonary autograft, the procedure is called Ross-Konno.[3] An alternative to a pulmonary homograft is the stentless xenograft roots such as the Freestyle Porcine Aortic Root by Medtronic.[2][12] An external Dacron graft can be used to reinforce the pulmonary autograft.[2]

Recovery

[edit]After the operation, good blood pressure control prevents early dilatation of the new aortic root and allows the pulmonary autograft, now in the aortic position, to settle in its new environment.[10] Aftercare includes regular echocardiography and lifelong endocarditis prophylaxis.[1]

Epidemiology

[edit]Complications occur in 3% to 5% of cases with one to 3% chance of early death. The death rate is almost negligible in very experienced centres. 80% to 90% of cases survive 10 years, and 70% to 80% may live up to 20 years.[3] As of 2014, the Ross procedure comprises less than 1% of all aortic valve replacements in North America.[1]

History

[edit]Replacing a diseased aortic valve with an aortic valve from a cadaver was first performed by Donald Ross in England in June 1962, and shortly after in July 1962 by Brian Barratt-Boyes in Auckland, New Zealand.[11][13] In 1967 Ross took the normal pulmonary valve of a person with severe aortic valve disease, and placed it in the aortic position where the diseased aortic valve was removed.[11] To reconstruct the missing pulmonary outflow tract, a homograft stored and sterilised from a cadaver was used to replace the removed pulmonary valve.[11] In 1972, Ross introduced the technique using the root replacement method.[13] For 30 years he was almost the only surgeon performing the procedure, until it gained popularity.[11] Marian Ionescu in Leeds, in an attempt to seek other materials, unsuccessfully tried fascia lata from the person's own thigh to create a living valve.[11] He then tried successfully with cattle pericardium fixed with glutaraldehyde, and the procedure became widespread before then falling out of favour as they failed.[11] Then came pig valves (xenograft) before the 1980s trend for mechanical valves.[11] The Ross procedure was continued and modified by Magdi Yacoub, who used fresh valves from the explanted hearts of transplant recipients.[11]

Etymology

[edit]It has also been called the double-switch Ross procedure.[14]

Society

[edit]In 1997, to replace a bicuspid aortic valve, the Ross procedure was performed on Arnold Schwarzenegger.[15]

The procedure was more popular in the 1990s and then declined in use over the subsequent 20 years.[16] Data relating to the procedure is held in the Ross registry.[17]

Other animals

[edit]The procedure has been carried out in pigs and sheep for the purpose of research.[18]

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Bouhout, Ismail; Hammamsy, Ismail (2020). "38. The Ross procedure". In Raja, Shahzad G. (ed.). Cardiac Surgery: A Complete Guide. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 351–358. ISBN 978-3-030-24176-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Nappi, Francesco; Singh, Sanjeet Singh Avtaar; Bellomo, Francesca; Nappi, Pierluigi; Iervolino, Adelaide; Acar, Christophe (2021). "The Choice of Pulmonary Autograft in Aortic Valve Surgery: A State-of-the-Art Primer". BioMed Research International. 2021: 5547342. doi:10.1155/2021/5547342. ISSN 2314-6141. PMC 8060091. PMID 33937396.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Brown, Kristen N.; Kanmanthareddy, Arun (2022). "Aortic Valve Ross Operation". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30725934.

- ^ a b c d Moroi, Morgan K.; Bacha, Emile A.; Kalfa, David M. (2021). "The Ross procedure in children: a systematic review". Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 10 (4): 420–432. doi:10.21037/acs-2020-rp-23. ISSN 2225-319X. PMC 8339620. PMID 34422554.

- ^ Bunce, Nicholas H.; Ray, Robin; Patel, Hitesh (2020). "30. Cardiology". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 1102. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5.

- ^ a b Morita, K.; Kurosawa, H. (April 2001). "[Indications for and clinical outcome of the Ross procedure: a review]". Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 102 (4): 330–336. ISSN 0301-4894. PMID 11344686.

- ^ a b c d e Etnel, Jonathan R.G.; Grashuis, Pepijn; Huygens, Simone A.; Pekbay, Begüm; Papageorgiou, Grigorios; Helbing, Willem A.; Roos-Hesselink, Jolien W.; Bogers, Ad J.J.C.; Mokhles, M. Mostafa; Takkenberg, Johanna J.M. (1 December 2018). "The Ross Procedure: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Microsimulation". Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 11 (12): e004748. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004748. PMID 30562065. S2CID 56477833.

- ^ a b c Van Hoof, Lucas; Verbrugghe, Peter; Jones, Elizabeth A. V.; Humphrey, Jay D.; Janssens, Stefan; Famaey, Nele; Rega, Filip (9 February 2022). "Understanding Pulmonary Autograft Remodeling After the Ross Procedure: Stick to the Facts". Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 9: 829120. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.829120. ISSN 2297-055X. PMC 8865563. PMID 35224059.

- ^ Tweddell, James S. (4 January 2021). "The root replacement remains the gold standard for the Ross procedure". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 59 (1): 234–235. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezaa366. ISSN 1873-734X. PMID 33188684.

- ^ a b c d e f Mazine, Amine; Ghoneim, Aly; El-Hamamsy, Ismail (1 May 2018). "The Ross Procedure: How I Teach It". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 105 (5): 1294–1298. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.01.048. ISSN 0003-4975. PMID 29481789.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Treasure, Tom (2000). "16. Cardiac surgery". In Silverman, Mark E.; Fleming, Peter R.; Hollman, Arthur; Julian, Desmond G.; Krikler, Dennis M. (eds.). British Cardiology in the 20th Century. Springer. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-4471-1199-3.

- ^ Kırali, Kaan; Gunay, Deniz (2017). "2. Isolated aortic root aneurysms". In Kırali, Kaan (ed.). Aortic Aneurysm. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 29. ISBN 978-953-51-2933-2.

- ^ a b Yankah, A Charles (June 2002). "Forty Years of Homograft Surgery". Asian Cardiovascular and Thoracic Annals. 10 (2): 97–100. doi:10.1177/021849230201000201. ISSN 0218-4923. PMID 12079928. S2CID 33689209.

- ^ Chang, Jen-Ping; Kao, Chiung-Lun; Hsieh, Ming-Jang (1 June 2002). "Double-switch Ross procedure". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 73 (6): 1988–1989. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03460-4. ISSN 0003-4975. PMID 12078818.

- ^ "Arnold Schwarzenegger's Heart Valve Surgeries (2020 Update)". www.heart-valve-surgery.com. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Mazine, Amine; Rocha, Rodolfo V.; El-Hamamsy, Ismail; Ouzounian, Maral; Yanagawa, Bobby; Bhatt, Deepak L.; Verma, Subodh; Friedrich, Jan O. (October 2018). "Ross Procedure vs Mechanical Aortic Valve Replacement in Adults". JAMA Cardiology. 3 (10): 978–987. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2018.2946. ISSN 2380-6583. PMC 6233830. PMID 30326489.

- ^ Aboud, Anas; Charitos, Efstratios I.; Fujita, Buntaro; Stierle, Ulrich; Reil, Jan-Christian; Voth, Vladimir; Liebrich, Markus; Andreas, Martin; Holubec, Tomas; Bening, Constanze; Albert, Marc; Fila, Petr; Ondrasek, Jiri; Murin, Peter; Lange, Rüdiger; Reichenspurner, Hermann; Franke, Ulrich; Gorski, Armin; Moritz, Anton; Laufer, Günther; Hemmer, Wolfgang; Sievers, Hans-Hinrich; Ensminger, Stephan (23 March 2021). "Long-Term Outcomes of Patients Undergoing the Ross Procedure". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 77 (11): 1412–1422. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.01.034. PMID 33736823. S2CID 232297352.

- ^ Van Hoof, Lucas; Claus, Piet; Jones, Elizabeth A. V.; Meuris, Bart; Famaey, Nele; Verbrugghe, Peter; Rega, Filip (July 2021). "Back to the root: a large animal model of the Ross procedure". Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 10 (4): 444–453. doi:10.21037/acs-2020-rp-21. ISSN 2225-319X. PMC 8339627. PMID 34422556.

Further reading

[edit]- Ross, D. N. (4 November 1967). "Replacement of aortic and mitral valves with a pulmonary autograft". Lancet. 2 (7523): 956–958. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(67)90794-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 4167516.

- Ross, Donald (1 December 1991). "Replacement of the aortic valve with a pulmonary autograft: The "Switch" operation". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 52 (6): 1346–1350. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(91)90032-L. ISSN 0003-4975. PMID 1755695.