Rosetta Stone decree

The Rosetta Stone decree, or the Decree of Memphis, is a Ptolemaic decree most notable for its bilingual and tri-scriptual nature, which enabled the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs. Issued by a council of priests confirming the royal cult of Ptolemy V in 196 BC at Memphis, it was written in Egyptian hieroglyphs, Egyptian Demotic and Ancient Greek. It mentions the Egyptian rebellion against the Greek rulers, otherwise known only through Greek sources and remains of graffiti.[1]

Context

[edit]The native Egyptian population at home was treated as second-class citizens by its Greek rulers and imperialists, while the economy had suffered because of the wars.[1] Seleucids, for example, won over the previously Ptolemaic-ruled territory of Coele-Syria, including Judaea, after the Battle of Panium (198 BC), while other territories were divided between Antiochus III the Great and Philip V of Macedon, who had seized several islands and cities in Caria and Thrace. During the reign of Ptolemy IV,[2] there was a long-standing revolt led by Horwennefer and by his successor Ankhwennefer, which had begun in the south of Egypt.[3] These were still ongoing when the young Ptolemy V was officially crowned at Memphis at the age of 12 (seven years after the start of his reign).[4] Egyptian cities joining the rebellion had faced economic and political consequences, such as the closure of ports, evidence has shown.[1]

Ptolemy V Epiphanes reigned from 204 to 181 BC, the son of Ptolemy IV Philopator and his wife and sister Arsinoe. He had become ruler at the age of five after the sudden death of both of his parents, who were murdered in a conspiracy that involved Ptolemy IV's mistress Agathoclea, according to contemporary sources. The conspirators effectively ruled Egypt as Ptolemy V's guardians[5][4] until a revolt broke out two years later under general Tlepolemus, when Agathoclea and her family were lynched by a mob in Alexandria. Tlepolemus, in turn, was replaced as guardian in 201 BC by Aristomenes of Alyzia, who was chief minister at the time of the Memphis decree.[6]

In the year after the majority of Ptolemy V., he was crowned at Memphis. For this event, the priests of Egypt assembled there and passed the decree.[7]

Text

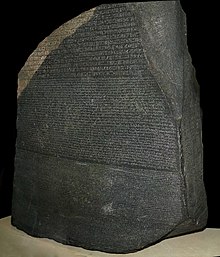

[edit]The text as recorded on the Rosetta Stone is considered the most complete of any of the surviving stelae, as it preserves the inscription in three scripts and two languages.[8] The first script is Egyptian hieroglyphs, the second is Demotic, and the third is Greek capitals. Only parts of the last fourteen lines of hieroglyphs remain; these correspond to the last twenty-eight lines of Greek text which is also damaged. The Demotic section is thirty-two lines of which the starts of fourteen are damaged (reading right to left). Fifty-four lines of Greek are present, twenty-six of which are damaged at the ends.[9] The majority of the damaged and missing sections of the hieroglyphic portion of the inscription can be restored using a copy of the decree from Damanhur (Hermopolis Magna) which was discovered in 1896. It post-dates the Rosetta Stone by fourteen years and as such has slightly different content, omitting details that are no longer relevant.[9]

Demotic was possibly the draft language of the decree, based on the rendering of the section describing the shrine housing the statue of the king. The wording makes the most sense in Demotic, with the Greek version not making much sense, and the hieroglyphic version lacking a determinative, rendering the meaning unspecific.[10] However, the text is a composite, with sections drawing on Greek or pharaonic traditions more than others.[11]

The inscription opens with the date of the decree:

[Year 9, Xandikos, day] 4 which corresponds to the second month of the Egyptians, Winter, day 18 (under) Pharaoh...[12]

This date corresponds to 27 March 196 B.C.[13] It does not record the day the decree was issued, but the date on which priests assembled as part of national festivals. On the Rosetta Stone, this is the coronation of the king, while on other stelae the occasion is the installation of a sacred animal.[14]

The text records that Ptolemy reduced or abolished taxes for the army and general population:

Of the dues and taxes existing in Egypt some he has cut and others he has abolished completely in order to cause the army and all other people to be happy in his time as [Pharaoh].[15]

Taxes levied on temples and their estates were also relaxed, with the order that "the divine revenues of the gods and the silver and grain which are given as syntaxis to their [temples] each year and the portions which accrue to the gods from vineyards and gardens and all other property over which they had rights under his father, that they remain in their possession..."[16] These tax breaks extended to the priesthood, as they were ordered "not to pay their tax for serving as priest above the amount they paid up to year one of his father. He has relieved the people [who are in] the offices of the temples of the sailing they make to Alexandria every year..."[16]

The generosity of the king is also extolled, having granted amnesty to prisoners, and outlawing pressganging.[17] Much space is dedicated to detailing the silver and grain given to temples, especially those centered on the animal cults with Ptolemy making "numerous benefactions to the Apis and Mnevis and the other animals which are sacred in Egypt... his heart being concerned with their affairs at all times, giving whatever was desired for their burials great and revered and bearing that which occurred for them (at) their temples when they celebrate festivals and make burnt offerings before them and the other things it is fitting to do."[18] Additionally, restoration and rebuilding of temples was carried out throughout Egypt.[18]

Earlier copies of the text recount the king's victory in the siege of Shekan (Lycopolis), which was "fortified by the enemy with every device."[19] He shows amnesty to "the men who had been on the other side in the rebellion which occurred in Egypt, to let them [return] to their homes and their property belong to them (again)."[19] The same clemency is not shown to the leaders of the rebellion, who are "slain at the stake" in Memphis as part of the festivities surrounding Ptolemy's ascension.[19] Later versions from Upper Egypt refer to the conquering of Thebes after its rebellion.[20]

The cult of the king is established, with temples throughout Egypt ordered to "...set up a statue of Pharaoh Ptolemy... in the (most) conspicuous place in the temple..."[21] The cult statue is to be made in Egyptian style, and is to be attended by priests three times daily, giving the image the same rituals they would perform for other gods.[21] The priests of all temples throughout Egypt are given the title "priests of the God who appears, whose goodness is perfect" in addition to their existing titles.[22] The specific appearance of the shrine in which the statue of the king is to be kept is described in detail, with royal crowns replacing the traditional uraeus frieze atop the shrine; the centre-most crown is to be the Double Crown. The papyrus and sedge are to appear on the corners, supporting a uraeus seated on a basket, "signifying Pharaoh who illumines Upper and Lower Egypt."[23] The shrine is to be "...set it in the sanctuary with the other gold shrines."[21] The feast days of the king are assigned as with the "last day of the fourth month of Summer" which is celebrated as the pharaoh's birthday; the "seventeenth day of the second month of Winter" is to be celebrated as the anniversary of his ascension.[24] The two days "...are to be celebrated as festival every month in all the temples of Egypt..."[24] Additionally, "they are to celebrate festival and procession in the temples and all of Egypt for Pharaoh Ptolemy... each year on the first day of the first month of Inundation for five days...[24] It is also stipulated that the statue of the king should take part in the major festivals of other deities, and that his statue should process with them.[23]

The worship of the king is also extended to the general population, with "ordinary people who so wish" to have in their homes a gold shrine similar to that found in the temples containing a statue of the king "and to celebrate the festivals and processions described above each year..."[22]

The text ends with instruction that temples throughout Egypt are to erect a stela bearing a copy of the decree recorded in three scripts and two languages.[22]

Copies

[edit]As a result of the instruction to erect copies of the decree in temples throughout Egypt, ten securely dated copies of the decree survive. The Rosetta Stone preserves the earliest and most complete copy of the decree, from year 9 of Ptolemy V’s reign. Two copies of the text were inscribed on the wall of Philae temple; one, known as Philensis II, dates to year 19, while the second, Philensis I, dates to year 21. The latest dated text is a year 23 stela from Asphynis. Duplicates of the various versions exist, with three copies of the Rosetta Stone text known from Naucratis, Elephantine, and Noub Taha; a further copy each is known for the Philensis inscriptions and Asphynis. Three additional fragmentary copies exist but they are not securely dated to Ptolemy's reign.[25]

The content of the text is broadly the same across the various copies, with later versions omitting or adding details as relevant. These include adding Ptolemy’s wife, Cleopatra I, to the royal cult after their marriage, and recording military expeditions. The specific details also vary according to the location of the stele; copies from Upper Egypt record the reconquering of Thebes in year 19 instead of the siege of Lycopolis.[25]

See also

[edit]- Decree of Canopus for Ptolemy III

- Decree of Memphis, or Raphia Decree, for Ptolemy IV

- Nubayrah Stele

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Silverstein (2023)

- ^ Parkinson et al. (1999) p. 29

- ^ Assmann (2003) p. 376

- ^ a b Clayton (2006) p. 211

- ^ Tyldesley (2006) p. 194

- ^ Bevan (1927) pp. 252–262

- ^ Pfeiffer 2015, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Quirke & Andrews 1988, p. 9.

- ^ a b Andrews 1985, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Andrews 1985, p. 43.

- ^ Quirke & Andrews 1988, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Quirke & Andrews 1988, p. 16.

- ^ Andrews 1985, p. 41.

- ^ Quirke & Andrews 1988, p. 8.

- ^ Quirke & Andrews 1988, p. 17.

- ^ a b Quirke & Andrews 1988, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Quirke & Andrews 1988, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Quirke & Andrews 1988, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Quirke & Andrews 1988, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Müller 1920, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c Quirke & Andrews 1988, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c Quirke & Andrews 1988, p. 22.

- ^ a b Quirke & Andrews 1988, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Quirke & Andrews 1988, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Quirke & Andrews 1988, pp. 7–8.

References

[edit]- Andrews, Carol (1985). The British Museum Book of the Rosetta Stone (First American ed.). New York: Peter Bedrick Books. ISBN 978-0-87226-034-4. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- Assmann, Jan; Jenkins, Andrew (2003). The Mind of Egypt: history and meaning in the time of the Pharaohs. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01211-0. Retrieved 2010-07-21.

- Bevan, E. R. (1927). The House of Ptolemy. Methuen. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicles of the Pharaohs: the reign-by-reign record of the rulers and dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28628-0.

- Müller, W. Max (1920). Egyptological Researches Vol. III: The Bilingual Decrees of Philae. Washington, D. C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Parkinson, Richard B.; Diffie, W.; Simpson, R. S. (1999). Cracking Codes: the Rosetta Stone and decipherment. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22306-6. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- Pfeiffer, Stefan (2015). Griechische und lateinische Inschriften zum Ptolemäerreich und zur römischen Provinz Aegyptus. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie (in German). Vol. 9. Münster: Lit. pp. 111–126.

- Silverstein, Jay (2023). "I dug for evidence of the Rosetta Stone's ancient Egyptian rebellion – here's what I found". The Conversation. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

- Quirke, Stephen; Andrews, Carol (1988). Rosetta Stone Facsimile Drawing With an Introduction and Translation. London: British Museum Publications Ltd.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2006). Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05145-3.