Ronald Reagan Supreme Court candidates

Speculation abounded over potential nominations to the Supreme Court of the United States by Ronald Reagan even before his presidency officially began, due to the advanced ages of several justices, and Reagan's own highlighting of Supreme Court nominations as a campaign issue. Reagan had promised "to appoint only those opposed to abortion and the 'judicial activism' of the Warren and Burger Courts".[1] Conversely, some opposed to Reagan argued that he could "appoint as many as five Justices" and would "use the opportunity to stack the Court against women, minorities and social justice".[2]

Sandra Day O'Connor nomination

[edit]During his 1980 campaign, Reagan pledged that, if given the opportunity, he would appoint the first female Supreme Court Justice.[3] That opportunity came in his first year in office when he nominated Sandra Day O'Connor to fill the vacancy created by the retirement of Justice Potter Stewart.[4] O'Connor was approved by the Senate by a vote of 99–0 on September 21, 1981.[5] Senator Max Baucus (D-MT) did not vote.[4]

William Rehnquist elevation

[edit]In his second term, Reagan elevated William Rehnquist to succeed Warren Burger as Chief Justice.[6] Rehnquist's confirmation was largely split along party lines, showing that he had not improved his standing among Senate Democrats since his contentious 1971 nomination to the Court.[6] Rehnquist's elevation to Chief Justice was approved by the Senate by a vote of 65–33 on September 17, 1986.[7] Senators Jake Garn (R-UT) and Barry Goldwater (R-AZ) did not vote. Senator Alan Simpson (R-WY) made public note on the Senate floor that Senator Garn's vote would have been to confirm had he been present.[6]

Democratic Senators who voted against Rehnquist's confirmation as an Associate Justice in 1971 and as Chief Justice in 1986 were Alan Cranston (CA), Daniel Inouye (HI), Edward M. Kennedy (MA) and Claiborne Pell (RI). Two Democrats who voted for Rehnquist's nomination as Associate Justice voted against his nomination as Chief Justice, Thomas Eagleton (MO) and Robert Byrd (WV).

Antonin Scalia nomination

[edit]After deciding to elevate Rehnquist to Chief Justice, Reagan considered both Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia to fill the vacant seat left by Rehnquist's elevation, but ultimately chose the younger and more charismatic Scalia.[8][9] Scalia was approved by the Senate by a vote of 98–0 on September 17, 1986.[10] Senators Jake Garn (R-UT) and Barry Goldwater (R-AZ) did not vote.[8]

Anthony Kennedy nomination

[edit]

Robert Bork selection

[edit]Supreme Court of the United States Associate Justice Lewis Franklin Powell Jr. was a moderate/conservative but the "swing vote" on close decisions, and even before his expected retirement on June 27, 1987, Senate Democrats had asked liberal leaders to form "a solid phalanx" to oppose whomever President Ronald Reagan nominated to replace him, assuming the appointment would send the court rightward; Democrats warned Reagan there would be a fight.[11] Reagan considered appointing Utah Senator Orrin Hatch to the seat, but Congress had approved $6,000 pay raises for Supreme Court Justices in February, raising a problem under the Ineligibility Clause of the United States Constitution, which prohibits a member of Congress from accepting an appointment for which the pay had been increased during that member's term. A memorandum by Assistant Attorney General Charles J. Cooper rejected the notion that a Saxbe fix—a rollback of the salary for the position—could satisfy the Ineligibility Clause.[12][13] Hatch had been on the short list of two finalists with Robert Bork,[14][15] but after the Ineligibility Clause had been brought to light, Hatch was no longer under consideration. Reagan nominated Robert Bork for the seat on July 1, 1987.

Within 45 minutes of Bork's nomination to the Court, Ted Kennedy (D-MA) took to the Senate floor with a strong condemnation of Bork in a nationally televised speech, declaring:

Robert Bork's America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens' doors in midnight raids, and schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the Government, and the doors of the Federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens.[16]

A brief was prepared for Joe Biden, head of the Senate Judiciary Committee, called the Biden Report. Bork later said in his best-selling[17] book The Tempting of America that the report "so thoroughly misrepresented a plain record that it easily qualifies as world class in the category of scurrility".[18] TV ads narrated by Gregory Peck attacked Bork as an extremist, and Kennedy's speech successfully fueled widespread public skepticism of Bork's nomination. The rapid response of Kennedy's "Robert Bork's America" speech stunned the Reagan White House; though conservatives considered Kennedy's accusations slanderous,[11] the attacks went unanswered for 2+1⁄2 months.[19]

A hotly contested United States Senate debate over Bork's nomination ensued, partly fueled by strong opposition by civil rights and women's rights groups concerned with what they claimed was Bork's desire to roll back civil rights decisions of the Warren and Burger courts. Bork is one of only four Supreme Court nominees to ever be opposed by the ACLU. Bork was also criticized for being an "advocate of disproportionate powers for the executive branch of Government, almost executive supremacy",[20] as demonstrated by his role in the Saturday Night Massacre.

During debate over his nomination, Bork's video rental history was leaked to the press, which led to the enactment of the 1988 Video Privacy Protection Act. His video rental history was unremarkable, and included such harmless titles as A Day at the Races, Ruthless People and The Man Who Knew Too Much. The list of rentals was originally printed by Washington D.C.'s City Paper.[21]

To pro-choice legal groups, Bork's originalist views and his belief that the Constitution does not contain a general "right to privacy" were viewed as a clear signal that, should he become a Justice of the Supreme Court, he would vote to reverse the Court's 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade. Accordingly, a large number of liberal advocacy groups mobilized to press for Bork's rejection, and the resulting 1987 Senate confirmation hearings became an intensely partisan battle. Bork was faulted for his bluntness before the committee, including his criticism of the reasoning underlying Roe v. Wade.

As chairman of the Judiciary Committee, Senator Joe Biden presided over Bork's hearing.[22] Biden stated his opposition to Bork soon after the nomination, reversing an approval in an interview of a hypothetical Bork nomination he had made the previous year and angering conservatives who thought he could not conduct the hearings dispassionately.[23] At the close, Biden won praise for conducting the proceedings fairly and with good humor and courage, as his 1988 presidential campaign collapsed in the middle of the hearings.[23][24] Biden framed his discussion around the belief that the U.S. Constitution provides rights to liberty and privacy that extend beyond those explicitly enumerated in the text, and that Bork's strong originalism was ideologically incompatible with that view.[24] Bork's nomination was rejected in the committee by a 9–5 vote,[24] and then rejected in the full Senate by a 58–42 margin.[25]

On October 23, 1987, the Senate rejected Bork's confirmation, with 42 senators voting in favor and 58 voting against. Senators David Boren (D-OK) and Ernest Hollings (D-SC) voted in favor, with Senators John Chafee (R-RI), Bob Packwood (R-OR), Arlen Specter (R-PA), Robert Stafford (R-VT), John Warner (R-VA) and Lowell P. Weicker Jr. (R-CT) all voting no.[25]

Douglas Ginsburg selection

[edit]Following Bork's defeat, Reagan announced his intention to nominate Douglas H. Ginsburg, a former Harvard Law professor whom Reagan had appointed to the District of Columbia Circuit the previous year. Ginsburg almost immediately came under some fire for an entirely different reason when NPR's Nina Totenberg[26] revealed that Ginsburg had used marijuana "on a few occasions" during his student days in the 1960s and while an Assistant Professor at Harvard in the 1970s. In 1991, a similar admission by then-nominee Clarence Thomas that he had used the drug during his law school days had no effect on his nomination.[27][a] Prior to being formally nominated, Ginsburg withdrew his name from consideration due to the allegations but remained on the federal appellate bench.

Anthony Kennedy selection

[edit]After Ginsburg's withdrawal, Reagan nominated Anthony Kennedy on November 11, 1987, and he was then confirmed to fill the vacancy on February 3, 1988.[29][30]

While vetting Kennedy for potential nomination, some of Reagan's Justice Department lawyers said Kennedy was too eager to put courts in disputes many conservatives would rather leave to legislatures, and to identify rights not expressly written in the Constitution.[31] Kennedy's stance in favor of privacy rights drew criticism; Kennedy cited Roe v. Wade and other privacy right cases favorably, which one lawyer called "really very distressing".[32]

In another of the opinions Kennedy wrote before coming to the Supreme Court, he criticized (in dissent) the police for bribing a child into showing them where the child's mother hid her heroin; Kennedy wrote that "indifference to personal liberty is but the precursor of the state's hostility to it".[33] The Reagan lawyers also criticized Kennedy for citing a report from Amnesty International to bolster his views in that case.[33]

Another lawyer said "Generally, [Kennedy] seems to favor the judiciary in any contest between the judiciary and another branch."[33]

Kennedy endorsed Griswold as well as the right to privacy, calling it "a zone of liberty, a zone of protection, a line that's drawn where the individual can tell the Government, 'Beyond this line you may not go.'"[34] This gave Kennedy more bipartisan support than Bork and Ginsburg. The Senate confirmed him by a vote of 97 to 0.[34]

Names frequently mentioned

[edit]Following is a list of individuals who were mentioned in various news accounts and books as having been considered by Reagan or being the most likely potential nominees for a Supreme Court appointment under Reagan:

United States Supreme Court (considered for elevation to Chief Justice)

[edit]- William Rehnquist (1924–2005) (nominated and elevated)

- Byron White[3] (1917–2002)

- Sandra Day O'Connor[3] (1930-2023)

United States Courts of Appeals

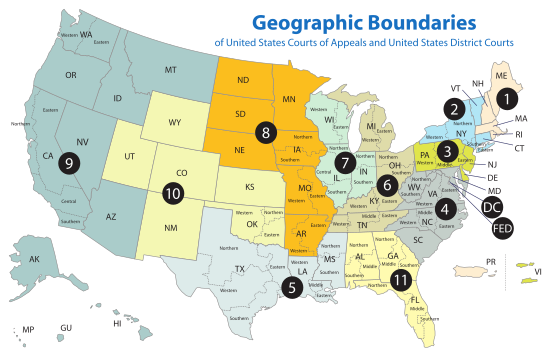

[edit]- Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

- Amalya Kearse[35][36] (born 1937)

- Ralph K. Winter Jr.[3] (1935-2020)

- Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- A. Leon Higginbotham Jr.[36] (1928-1998)

- Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

- William W. Wilkins Jr.[37] (born 1942)

- Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

- Patrick Higginbotham[3] (born 1938)

- Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

- Cornelia Groefsema Kennedy[3][35][36][38] (1923-2014)

- Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

- Pasco Bowman II (born 1933)[39][40]

- Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

- Anthony Kennedy (born 1936) (Nominated and Confirmed)[36][37]

- J. Clifford Wallace[3][35] (born 1928)

- Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

- Gerald Bard Tjoflat (born 1929)[41]

- Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

- Robert Bork (1927-2012) (Nomination rejected)[36]

- Douglas H. Ginsburg (born 1946) (Nomination withdrawn)[37]

- Antonin Scalia (1936-2016) (Nominated and Confirmed)

- Malcolm Richard Wilkey[36] (1918-2009)

United States District Courts

[edit]- Charles E. Simons Jr. (1916-1999) — chief judge of the United States District Court for the District of South Carolina[35]

- Sam C. Pointer Jr. (1934-2008) — judge, United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama[41]

State Supreme Courts

[edit]- Mary S. Coleman (1914-2001) — Chief Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court[3]

- C. Bruce Littlejohn (1913-2007) — Associate Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court[35]

- Dallin H. Oaks (born 1932) — Associate Justice of the Utah Supreme Court[42]

- Frank K. Richardson (1914-1999) — Associate Justice of the California Supreme Court[36]

- Susie Sharp (1907-1996) — Chief Justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court[3]

- David H. Souter (born 1939) — Associate Justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court (Nominated in 1990 by George H. W. Bush and Confirmed)[37]

Administration officials

[edit]- William P. Clark Jr. (1931-2013) — Deputy Secretary of State[35][36][43]

- Elizabeth Dole (born 1936) — assistant to the President for public liaison, later Secretary of Transportation[35][36][43]

- Edwin Meese (born 1931) — Counselor to the President and later Attorney General[43]

- William French Smith (1917-1990) — Attorney General[35][36]

Other backgrounds

[edit]- Anne L. Armstrong (1927-2008) — former ambassador to Britain[36]

- Sylvia Bacon (1931-2023) — District of Columbia superior court judge[36][38]

- William Thaddeus Coleman Jr. (1920-2017) — former United States Secretary of Transportation[36]

- Orrin Hatch (1934-2022) — senator from Utah[14]

- Rita Hauser (born 1934) — former representative to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights[36][38]

- Carla Anderson Hills (born 1934) — former United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development[36][38]

- Mildred Lillie (1915-2002) — California appeals court Judge[36][38]

- Wade H. McCree (1920-1987) — former United States Solicitor General[36]

- Sandra Day O'Connor (1930-2023) — judge of the Arizona Court of Appeals (Nominated and Confirmed)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ David M. O'Brien, Storm Center, Sixth Edition (2003), p. 69.

- ^ The National Journal (November 1, 1980), Vol. 12, No. 44; Pg. 1838.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i David M. O'Brien, Storm Center, Sixth Edition (2003), p. 70.

- ^ a b "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes — Nomination of Sandra Day O'Connor" (PDF). senate.gov.

- ^ "Senate – September 21, 1981" (PDF). Congressional Record. 127 (16). U.S. Government Printing Office: 21375. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes — Nomination of William Rehnquist, senate.gov

- ^ "Senate — September 17, 1986" (PDF). Congressional Record. 132 (17). U.S. Government Printing Office: 23803. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes — Nomination of Antonin Scalia" (PDF). senate.gov.

- ^ David M. O'Brien, Storm Center, Sixth Edition (2003), p. 71.

- ^ "Senate — September 17, 1986" (PDF). Congressional Record. 132 (17). U.S. Government Printing Office: 23813. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Manuel Miranda (2005-08-24). "The Original Borking". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ Memorandum for the Counselor to the Attorney General, from Charles J. Cooper, Assistant Attorney General, Office of Legal Counsel, Re: Ineligibility of Sitting Congressman to Assume a Vacancy on the Supreme Court (Aug. 24, 1987)

- ^ Volokh, Eugene (2008-11-24). "Hillary Clinton and the Emoluments Clause" (Blog). The Volokh Conspiracy. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ a b Molotsky, Irvin (1987-06-28). "Inside Fight Seen Over Court Choice" (Special). The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ Church, George J.; Beckwith, David; Constable, Anne (1987-07-06). "The Court's Pivot Man". Time. Archived from the original (Article) on December 3, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ Reston, James (July 5, 1987). "WASHINGTON; Kennedy And Bork". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ "Robert H. Bork". Harper Collins. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ Damon W. Root (2008-09-09). "Straight Talk Slowdown". Reason. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ Gail Russell Chaddock (2005-07-07). "Court nominees will trigger rapid response". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ New Views Emerge of Bork's Role in Watergate Dismissals, The New York Times.

- ^ "The Bork Tapes Saga". The American Porch. Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ Almanac of American Politics 2008, p. 364.

- ^ a b Bronner, Ethan (1989). Battle for Justice: How the Bork Nomination Shook America. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-02690-6. pp. 138–139, 214, 305.

- ^ a b c Greenhouse, Linda (1987-10-08). "Washington Talk: The Bork Hearings; For Biden: Epoch of Belief, Epoch of Incredulity". The New York Times.

- ^ a b U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes - Nomination of Robert Bork, senate.gov

- ^ Nina Totenberg, NPR Biography.

- ^ The Washington Post: "Media Frenzies in Our Time".

- ^ Hall, Kermit, ed., The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, page 339, Oxford Press, 1992.

- ^ "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes — Nomination of Anthony Kennedy" (PDF). senate.gov.

- ^ "Anthony M. Kennedy". Supreme Court Historical Society. 1999. Archived from the original on 2007-11-03. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 53.

- ^ Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 54.

- ^ a b c Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court.2007. Penguin Books. Page 55.

- ^ a b Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 189.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Advisers Said to Narrow Choice for Seat on Court", The New York Times (June 23, 1981), A-15, Column 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Elizabeth Olson, "Reagan may have strong hand over high court", United Press International (November 9, 1980).

- ^ a b c d Greenhouse, Linda (1987-10-29). "A NEW CONTENDER IS SEEN FOR COURT". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ^ a b c d e Biskupic, Joan (2005). Sandra Day O'Connor: How the First Woman on the Supreme Court Became Its Most Influential Justice. Ecco Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-06-059018-5.

- ^ ‘KC Judge Being Considered for Vacancy: Appellate Jurist Was also Mentioned for High Court Opening in 1987’; The Kansas City Star, July 22, 1990, p. 2.

- ^ ‘Administration About To Name California’s Kennedy to Court’; San Francisco Examiner, November 10, 1987, pp. 1, 5.

- ^ a b Yalof, David Alistair (1999). Pursuit of Justices: Presidential Politics and the Selection of Supreme Court Nominees from Herbert Hoover to George W. Bush. University of Chicago Press. p. 162. ISBN 0226945456.

- ^ Gehrke, Robert (August 18, 2015). "LDS apostle was studied for '81 court". Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c Steven R. Weisman, "Reagan Aides Say 'Short List' of Candidates for Court is Ready", The New York Times (July 1, 1981), A-19, Column 1.