Rod Coronado

Rod Coronado | |

|---|---|

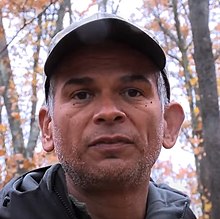

Coronado, 2014 | |

| Born | Rodney Adam Coronado July 3, 1966 |

| Known for | Animal rights, environmental activism, arson |

Rodney Adam Coronado (born July 3, 1966) is an indigenous American animal rights and environmental activist known for his militant direct actions in the late 1980s and 1990s. As part of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, he sank two whaling ships and destroyed Iceland's sole whale-processing facility in 1986. He led the Animal Liberation Front's Operation Bite Back campaign against the fur industry and its supporting institutions in the early 1990s, which was involved in multiple firebombings. Following an attack on a Michigan State University mink research center in early 1992, Coronado was jailed for nearly five years. He later admitted to being the sole perpetrator. The 1992 federal Animal Enterprise Protection Act was created in response to his actions. The operation continued with a focus on liberating animals rather than property destruction. Coronado also worked with Earth First.

His activism continued in the 2000s. He was jailed another eight months in 2004 for sabotaging an Arizona mountain lion hunt and was targeted under an anti-terrorism law in 2006 for having recounted details of his Michigan State incendiary device in a public setting. During his active sentence, he renounced violent tactics, influenced by years of imprisonment and his new fatherhood. He served an additional year for the incendiary device charge and an additional four months for a probation violation. Since 2013, Coronado has been involved in gray wolf conservation in the contiguous United States. He founded Wolf Patrol, a nonprofit that monitors treatment of wolves and reports illegal wolf hunting.

Early life and activism

[edit]Rod Coronado was born in 1966[1] of Pascua Yaqui Indigenous ancestry and raised in California.[2] (He was not registered with the tribe as of 2006 for political reasons.[3]) As a child, he was teased for his love of nature. Among his formative experiences, the television video of a Canadian commercial seal hunt affected him deeply. He joined the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, an anti-whaling activist direct action group, as a teenager. Coronado later joined the radical environmentalist group Earth First!, and the Animal Liberation Front, an underground animal rights group that released animals from fur farms and research facilities.[2]

In November 1986, Rod Coronado and David Howitt sunk two whaling ships in Reykjavík harbor and sabotaged Iceland's sole whale-processing facility in Hvalfjord. The two members of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society had spent weeks in Iceland working at a fish processing factory and plotting their action. On November 8, the pair dismantled the Hvalfjord facility's computer files, refrigeration, and laboratory equipment with cyanic acid and sledgehammers over eight hours. They drove 50 miles south to Reykjavík, where they boarded two of the whaling company's four ships and opened their sea valves. Watchmen prevented them from accessing the other ships. Coronado and Howitt fled to Luxembourg via plane.[4] About $2 million in damage had been done (equivalent to $6 million in 2023).[5]

Coronado designed and led the Animal Liberation Front's early 1990s campaign against the fur industry and its supporting research institutions, known as Operation Bite Back. The first attack, in June 1991, was arson on Oregon State University's experimental mink farm, burning research records and leading to the facility's closure. Within a week, another attack firebombed the Edmonds, Washington, Northwest Farm Food Cooperative, which supplied mink feed. In August, activists attacked a Washington State University mink farm. In February 1992, Coronado and two other Animal Liberation Front activists burned a Michigan State University mink research center, causing $200,000 in damages and incinerating 32 years of research. In 1995, Coronado was sentenced to 57 months of jail, three years probation, and a $2 million fine.[6] Coronado had said that he was not involved in the attack apart from serving as a spokesperson for the Animal Liberation Front, and took the lesser charge of aiding in the attack to avoid a trial and drop charges from other attacks. Only 25 years later did Coronado admit to being the attack's sole perpetrator.[7] The campaign continued during his imprisonment with a focus on freeing animals rather than economic sabotage.[6] The 1992 federal Animal Enterprise Protection Act, which was built to protect animal-based businesses, had been crafted largely in response to Coronado.[8] While in prison, Coronado created and wrote the magazine Strong Hearts.[2]

Following threats of mountain lions looming in the foothills of Tucson, the Arizona Game and Fish Department announced a hunt within the Sabino Canyon area on March 10, 2004. With split scientific opinion on the merit of lion relocation and ten days of protests, the department attempted to move the lions but found few tracks. The climax of the protests was Coronado's arrest, on March 24, for spreading lion scent in the park to sabotage tracking dogs. The hunt was called off four days later.[9] Coronado, Earth First activist Matthew Crozier, and an Esquire journalist accompanying them were charged with trespassing during an emergency order of closure and interfering with an officer.[10][11] From 2006 to 2007, Coronado served eight months[12] of a ten-month federal sentence.[13]

Amidst the backdrop of the Green Scare, a period of federal crackdown on radical environmental and animal rights activism,[14] the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) arrested Coronado in February 2006[12] as part of its Operation Backfire.[15] Years prior, in August 2003, Coronado gave a speech in San Diego on activist rights that the FBI recorded. In response to an audience question about the Michigan State arson, Coronado used a nearby juice container to explain how the incendiary device worked.[13] A grand jury led to charges that Coronado demonstrated an explosive device with intent to commit a crime.[12]

Fatherhood and years of imprisonment changed Coronado's priorities.[7] Later in 2006, before the incendiary device case went to court and while serving time for the mountain lion case, Coronado wrote an open letter from prison renouncing violence as a means for social pressure[7] in consideration of how legal efforts and prison time had affected his life, family, and young children. This approach was a departure for Coronado, who by now was an underground celebrity among environmental and animal rights radicals. He had become known for his illegal direct actions and longstanding public advocacy for militant tactics, with prominent recent appearances on national television (60 Minutes in 2005) and speaking at an American University (2003).[12] But parenting, he wrote, makes parents "practice the very principles [they] seek to teach [their] children".[7]

The incendiary device case ended as a mistrial with a hung jury.[16] He pled guilty and in March 2008 was sentenced to a year of prison in exchange for other dropped cases and to "move on with [his] life", having already committed to a changed outlook on violence.[17] Coronado was released in 2009. The next year, a judge sent him back to prison for four months after Coronado was found to have friended activist Mike Roselle on Facebook in violation of his probation.[18]

Coronado has been involved with grey wolf conservation in the contiguous United States since 2013. He founded Wolf Patrol, a non-profit environmental group that monitors treatment of wolves and reports illegal wolf hunting.[7]

Personal life

[edit]Coronado was married in 2007 and has two children:[17] a son born in 2001 and his wife's daughter, born prior to their partnership.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Watkins, Mary; Bradshaw, G. A. (June 25, 2019). Mutual Accompaniment and the Creation of the Commons. Yale University Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-300-23614-9.

- ^ a b c Norrell, Brenda (December 8, 1999). "Sierra Club honors Yaqui animal rights activists". Indian Country Today. p. B2. ISSN 1066-5501. ProQuest 362610777.

- ^ Beal, Tom (July 26, 2006). "Feathers bring more charges for activist". Arizona Daily Star. pp. B1–B2.

- ^ Derr & McNamara 2003, p. 28.

- ^ "Saboteurs Wreck Whale-Oil Plant in Iceland". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 11, 1986. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Posluszna, Elzbieta (January 29, 2015). Environmental and Animal Rights Extremism, Terrorism, and National Security. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-12-801704-3.

- ^ a b c d e Hawkins, Derek (February 27, 2017). "'We wanted them to live in fear': Animal rights activist admits to university bombing 25 years later". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 1872561529 Gale A483080985. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ Zellhoefer, Aaron (2013). "Animal Enterprise Acts and the Prosecution of the 'SHAC 7': An Insider's Perspective". In Socha, Kim; Blum, Sarahjane (eds.). Confronting Animal Exploitation: Grassroots Essays on Liberation and Veganism. McFarland. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-7864-6575-0.

In fact, this law was primarily developed to stop one individual—Rodney Coronado.

- ^ Davis, Tony (May 24, 2004). "Cougar hunt creates uproar; Following a sensational search, Arizona residents push for tougher protections for mountain lions". High Country News. p. 5. ISSN 0191-5657. ProQuest 363058233.

- ^ Swedlund, Eric (December 10, 2004). "New charge for Sabino lion-hunt intruders". Arizona Daily Star. p. B2. ISSN 0888-546X. ProQuest 389594480.

- ^ Powers, Ashley (May 4, 2004). "THE OUTDOORS DIGEST; Journalist snared; When reporters accompany activists, do they get the story or do they become the story?". Los Angeles Times. p. F.3. ISSN 0458-3035. ProQuest 421925773.

- ^ a b c d e Archibold, Randal C. (May 3, 2007). "Facing Trial Under Terror Law, Radical Claims a New Outlook". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Carter, Edward C. (2016). Criminal Law and Procedure for the Paralegal. Wolters Kluwer. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-4548-7352-5.

- ^ "Rev. of Operation Bite Back: Rod Coronado's War to Save American Wilderness". Kirkus Reviews. May 1, 2009. ISSN 1948-7428. ProQuest 917359296.

- ^ Bezanson, Kate; Webber, Michelle (2016). Rethinking Society in the 21st Century, Fourth Edition: Critical Readings in Sociology. Canadian Scholars’ Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-55130-936-1. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ "California: Mistrial in Ecoterror Case". The New York Times. The Associated Press. September 21, 2007. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Moran, Greg (April 10, 2008). "Animal rights activist tells of regret before sentencing". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ Kouddous, Sharif Abdel; Goodman, Amy (September 8, 2010). "Jailed for Facebook Friending: Animal Rights Activist Rod Coronado Ordered Back to Prison After Accepting Friend Request from Fellow Activist". Democracy Now!. Archived from the original on October 10, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Derr, Patrick; McNamara, Edward (2003). "Reykjavik Raiders". Case Studies in Environmental Ethics. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 27–33. ISBN 978-0-7425-7264-5.

- Kuipers, Dean (2009). Operation Bite Back: Rod Coronado's War to Save American Wilderness. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-60819-142-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Coronado, Rod (2004). "Direct Actions Speak Louder than Words" (PDF). In Best, Steven; Nocella II, Anthony J. (eds.). Terrorists or Freedom Fighters? Reflections on the Liberation of Animals. Lantern Books. pp. 178–184. ISBN 978-1590560549. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Coronado, Rod (2011). Flaming Arrows: Collected Writings of Animal Liberation Front Warrior Rod Coronado. Warcry Communications. ISBN 978-0-9842844-5-0

- Brown, Alleen; Knefel, John (September 1, 2018). "The FBI Tried to Use the #MeToo Moment to Pressure an Environmental Activist Into Becoming an Informant". The Intercept. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- Kuipers, Dean (June 1995). "The Tracks of the Coyote". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- Rietmulder, Michael (November 2, 2015). "How Wolf Patrol's Rod Coronado is pissing off Wisconsin hunters". City Pages. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Scarce, Rik. Eco-Warriors (2006) (ISBN 1-59874-028-8)

- Taylor, Bron (2008). "Rodney Coronado and the Animal Liberation Front". Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature. A&C Black. pp. 1331–. ISBN 978-1-4411-2278-0. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Rod Coronado at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rod Coronado at Wikimedia Commons

- 1966 births

- American animal rights activists

- American people convicted of arson

- American anarchists

- American environmentalists

- American people of Yaqui descent

- Animal Liberation Front

- Earth Liberation Front

- American prisoners and detainees

- Eco-terrorism

- Green anarchists

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government

- Living people

- Saboteurs

- Sea Shepherd Conservation Society

- Terrorism in the United States