Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson | |

|---|---|

One of many speculative portraits[a] | |

| Born | c. 1565 |

| Disappeared | 23 June 1611 (aged 45–46) James Bay, North America |

| Other names | Hendrick Hudson (in Dutch) |

| Occupation(s) | Sea explorer, navigator |

| Years active | 1607–1611 (as explorer) |

| Employers | |

| Known for |

|

| Children | John Hudson (c. 1591–1611) |

Henry Hudson (c. 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the Northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 1608, Hudson made two attempts on behalf of English merchants to find a rumoured Northeast Passage to Cathay via a route above the Arctic Circle. In 1609, he landed in North America on behalf of the Dutch East India Company and explored the region around the modern New York metropolitan area. Looking for a Northwest Passage to Asia[3] on his ship Halve Maen ("Half Moon"),[4] he sailed up the Hudson River, which was later named after him, and thereby laid the foundation for Dutch colonization of the region. His contributions to the exploration of the New World were significant and lasting. His voyages helped to establish European contact with the native peoples of North America and contributed to the development of trade and commerce.

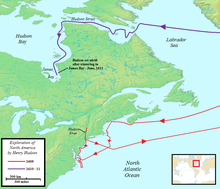

On his final expedition, while still searching for the Northwest Passage, Hudson became the first European to see Hudson Strait and the immense Hudson Bay.[5] In 1611, after wintering on the shore of James Bay, Hudson wanted to press on to the west, but most of his crew mutinied. The mutineers cast Hudson, his son, and six others adrift; what then happened to the Hudsons and their companions is unknown.[6]

Early life

Virtually nothing of Hudson's early life is known for certain.[7][8] His year of birth is variously estimated between 1560 and 1570.[9][10][11] He may have been born in London and it is possible that his father was an alderman of that city.[7][12] When Hudson first entered the historical record in 1607, he was already an experienced mariner with sufficient credentials to be commissioned the leader of an expedition charged with a search for a trade route across the North Pole.[12]

Exploration

Expeditions of 1607 and 1608

In 1607, the Muscovy Company of England hired Hudson to find a northerly route to the Pacific coast of Asia. At the time, the English were engaged in an economic battle with the Dutch for control of northwest routes. It was thought that, because the sun shone for three months in the northern latitudes in the summer, the ice would melt, and a ship could make it across the "top of the world".[7]

On 1 May 1607, Hudson sailed with a crew of ten men and a boy on the 80-ton Hopewell.[13][14] They reached the east coast of Greenland on 13 May, coasting northward until 22 May. Here the party named a headland "Young's Cape", a "very high mount, like a round castle" near it "Mount of God's Mercy" and land at 73° north latitude "Hold with Hope". After turning east, they sighted "Newland" (Spitsbergen) on 27 May near the mouth of the great bay Hudson later simply named the "Great Indraught" (Isfjorden).[7]

On 13 July, Hudson and his crew estimated that they had sailed as far north as 80° 23′ N,[b] but had more likely only reached 79° 23′ N. The following day they entered what Hudson later in the voyage named "Whales Bay" (Krossfjorden and Kongsfjorden), naming its northwestern point "Collins Cape" (Kapp Mitra) after his boatswain, William Collins. They sailed north the following two days. On 16 July, they reached as far north as Hakluyt's Headland (which Thomas Edge says Hudson named on this voyage) at 79° 49′ N, thinking they saw the land continue to 82° N (Svalbard's northernmost point is 80° 49′ N) when really it trended to the east. Encountering ice packed along the north coast, they were forced to turn back south. Hudson wanted to make his return "by the north of Greenland to Davis his Streights (Davis Strait), and so for Kingdom of England", but ice conditions would have made this impossible. The expedition returned to Tilbury Hope on the River Thames on 15 September.

Hudson reported large numbers of whales in Spitsbergen waters during this voyage. Many authors[c] credit his reports as the catalyst for several nations sending whaling expeditions to the islands. This claim is contentious; others have pointed to strong evidence that it was Jonas Poole's reports in 1610, that led to the establishment of English whaling, and voyages of Nicholas Woodcock and Willem Cornelisz van Muyden in 1612, which led to the establishment of Dutch, French and Spanish whaling.[15] The whaling industry was built by neither Hudson nor Poole—both were dead by 1612.

In 1608, English merchants of the East India and Muscovy Companies again sent Hudson in the Hopewell to attempt to locate a passage to the Indies, this time to the east around northern Russia. Leaving London on 22 April, the ship travelled almost 2,500 mi (4,000 km), making it to Novaya Zemlya well above the Arctic Circle in July, but even in the summer they found the ice impenetrable and turned back, arriving at Gravesend on 26 August.[16]

Alleged discovery of Jan Mayen

According to Thomas Edge, "William [sic] Hudson" in 1608 discovered an island he named "Hudson's Tutches" (Touches) at 71° N,[17] the latitude of Jan Mayen. However, records of Hudson's voyages suggest that he could only have come across Jan Mayen in 1607 by making an illogical detour, and historians have pointed out that Hudson himself made no mention of it in his journal.[d] There is also no cartographical proof of this supposed discovery.[18]

Jonas Poole in 1611 and Robert Fotherby in 1615 both had possession of Hudson's journal while searching for his elusive Hold-with-Hope—which is now believed to have been on the east coast of Greenland—but neither had any knowledge of any discovery of Jan Mayen, an achievement which was only later attributed to Hudson. Fotherby eventually stumbled across Jan Mayen, thinking it a new discovery and naming it "Sir Thomas Smith's Island",[19] though the first verifiable records of the discovery of the island had been made a year earlier, in 1614.

Expedition of 1609

In 1609, Hudson was chosen by merchants of the Dutch East India Company in the Netherlands to find an easterly passage to Asia. While awaiting orders and supplies in Amsterdam, he heard rumours of a northwest route to the Pacific through North America.[20] Hudson had been told to sail through the Arctic Ocean north of Russia, into the Pacific and so to the Far East. Hudson departed Amsterdam on 4 April, in command of the Dutch ship Halve Maen[21] (English: Half Moon). He could not complete the specified (eastward) route because ice blocked the passage, as with all previous such voyages, and he turned the ship around in mid-May while somewhere east of Norway's North Cape. At that point, acting outside his instructions, Hudson pointed the ship west and decided to try to seek a westerly passage through North America.[22]

They reached the Grand Banks of Newfoundland on 2 July, and in mid-July made landfall near the LaHave area of Nova Scotia.[23] Here they encountered Indigenous people who were accustomed to trading with the French; they were willing to trade beaver pelts, but apparently no trades occurred.[24] The ship stayed in the area about ten days, the crew replacing a broken mast and fishing for food. On the 25 July, a dozen men from the Halve Maen, using muskets and small cannon, went ashore and assaulted the village near their anchorage. They drove the people from the settlement and took their boat and other property—probably pelts and trade goods.[25]

On 4 August, the ship was at Cape Cod, from which Hudson sailed south to the entrance of the Chesapeake Bay. Rather than entering the Chesapeake he explored the coast to the north, finding Delaware Bay but continuing on north. On 3 September, he reached the estuary of the river that initially was called the "North River" or "Mauritius" and now carries his name. He was not the first European to discover the estuary, though, as it had been known since the voyage of Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524.

On 6 September 1609, John Colman of his crew was killed by natives with an arrow to his neck.[26] Hudson sailed into the Upper New York Bay on 11 September,[27] and the following day encountered a group of 28 Lenape canoes, buying oysters and beans from the Native Americans, and then began a journey up what is now known as the Hudson River.[28] Over the next ten days his ship ascended the river, reaching a point near Stuyvesant Landing (Old Kinderhook), and the ship's boat with five crew members ventured to the vicinity of present-day Albany.[29]

On 23 September, Hudson decided to return to Europe.[30] He put in at Dartmouth, England on 7 November, and was detained by authorities who wanted access to his log. He managed to pass the log to the Dutch ambassador to England, who sent it, along with his report, to Amsterdam.[31]

While exploring the river, Hudson had traded with several native groups, mainly obtaining furs. His voyage was used to establish Dutch claims to the region and to the fur trade that prospered there when a trading post was established at Albany in 1614. New Amsterdam on Manhattan Island became the capital of New Netherland in 1625.

Expedition of 1610–1611

In 1610, Hudson obtained backing for another voyage, this time under the English flag. The funding came from the Virginia Company and the British East India Company. At the helm of his new ship, the Discovery, he stayed to the north (some claim he had deliberately stayed too far south on his Dutch-funded voyage),[citation needed] reached Iceland on 11 May, the south of Greenland on 4 June, and rounded the southern tip of Greenland.

On 25 June, the explorers reached what is now the Hudson Strait at the northern tip of Labrador. Following the southern coast of the strait on 2 August, the ship entered Hudson Bay. Excitement was very high due to the expectation that the ship had finally found the Northwest Passage through the continent. Hudson spent the following months mapping and exploring its eastern shores, but he and his crew did not find a passage to Asia. In November, the ship became trapped in the ice in James Bay, and the crew moved ashore for the winter.

Mutiny

When the ice cleared in the spring of 1611, Hudson planned to use his Discovery to further explore Hudson Bay with the continuing goal of discovering the Passage; however, most of the members of his crew ardently desired to return home. Matters came to a head and much of the crew mutinied in June. Descriptions of the successful mutiny are one-sided, because the only survivors who could tell their story were the mutineers and those who went along with the mutiny.

In the latter class was ship's navigator, Abacuk Pricket, a survivor who kept a journal that was to become one of the sources for the narrative of the mutiny. According to Pricket, the leaders of the mutiny were Henry Greene and Robert Juet.[32] The latter, a navigator, had accompanied Hudson on the 1609 expedition, and his account is said to be "the best contemporary record of the voyage".[33] Pricket's narrative tells how the mutineers set Hudson, his teenage son John, and seven crewmen—men who were either sick and infirm or loyal to Hudson—adrift from the Discovery in a small shallop, an open boat, effectively marooning them in Hudson Bay. The Pricket journal reports that the mutineers provided the castaways with clothing, powder and shot, some pikes, an iron pot, some food, and other miscellaneous items.

Disappearance

After the mutiny, Hudson's shallop broke out oars and tried to keep pace with the Discovery for some time. Pricket recalled that the mutineers finally tired of the David–Goliath pursuit and unfurled additional sails aboard the Discovery, enabling the larger vessel to leave the tiny open boat behind. Hudson and the other seven aboard the shallop were never seen by Europeans again. Despite subsequent searches, including those conducted by Thomas Button in 1612 and by Zachariah Gillam in 1668–1670, their fate is unknown.[34][35]

Pricket's reliability

While Pricket's account is one of the few surviving records of the voyage, its reliability has been questioned by some historians. Pricket's journal and testimony have been severely criticized for bias, on two grounds. Firstly, prior to the mutiny the alleged leaders of the uprising, Greene and Juet, had been friends and loyal seamen of Hudson. Secondly, Greene and Juet did not survive the return voyage to England (Juet, who had been the navigator on the return journey, died of starvation a few days before the company reached Ireland[33]). Pricket knew he and the other survivors of the mutiny would be tried in England for piracy, and it would have been in his interest, and the interest of the other survivors, to put together a narrative that would place the blame for the mutiny upon men who were no longer alive to defend themselves.

The Pricket narrative became the controlling story of the expedition's disastrous end. Only eight of the thirteen mutinous crewmen survived the return voyage to Europe. They were arrested in England, and some were put on trial, but no punishment was imposed for the mutiny. One theory holds that the survivors were considered too valuable as sources of information to execute, as they had travelled to the New World and could describe sailing routes and conditions.[36]

Later developments

In 1612, Nicolas de Vignau claimed he saw wreckage of an English ship on the shores of James Bay, located on the southern end of Hudson Bay—while this was discounted at the time by Samuel de Champlain, historians believe it may have credence.[37]

British-born Canadian author Dorothy Harley Eber (1925–2022) collected Inuit testimonies that she thought made reference to Hudson and his son after the mutiny. According to these, an old man with a long white beard and a young boy arrived in a small wooden boat. The Inuit had never seen a white person before, but they took them to an encampment and fed them. After the old man died, the Inuit tethered the boy to one of their houses so he would not run away. Despite the long time passed, the story might be given some credence after long-ignored Inuit testimonies proved reliable enough to lead to the discovery of the wrecks of the two ships in Franklin's lost expedition, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, in the 2010s. Charles Francis Hall, who searched for Franklin in the mid-19th century, also collected Inuit stories that he interpreted as references to the even earlier expedition of Martin Frobisher, who explored the area and mined fool's gold in 1578.[38]

In the late 1950s, a 150-pound (68 kg) stone near Deep River, Ontario, which is approximately 600 kilometres (370 mi) south of James Bay, was found to have carving on it with Hudson's initials (H. H.), the year 1612, and the word "captive".[39] While lettering on the stone was consistent with English maps of the 17th century, the Geological Survey of Canada was unable to determine when the carving was made.[37]

Legacy

The bay visited by and named after Hudson is three times the size of the Baltic Sea, and its many large estuaries afford access to otherwise landlocked parts of Western Canada and the Arctic. This allowed the Hudson's Bay Company to exploit a lucrative fur trade along its shores for more than two centuries, growing powerful enough to influence the history and present international boundaries of western North America.[40]

Along with Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait in Canada, many other topographical features and landmarks are named for Hudson. The Hudson River in New York and New Jersey is named after him, as are Hudson County, New Jersey, the Henry Hudson Bridge, the Henry Hudson Parkway, and the city of Hudson, New York.[41]

See also

- Age of Discovery

- List of people who disappeared before 1970

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea

References

Notes

- ^ All known portraits used to represent Henry Hudson were drawn after his death.[1][2]

- ^ Observations made during this voyage were often wrong, sometimes greatly so. See Conway 1906.

- ^ Sandler 2008, p. 407; Umbreit 2005, p. 1; Shorto 2004, p. 21; Mulvaney 2001, p. 38; Davis et al. 1997, p. 31; Francis 1990, p. 30; Rudmose-Brown 1920, p. 312; Chisholm 1911, p. 942.

- ^ "The above relation by Thomas Edge is obviously incorrect. Hudson's Christian name is wrongly given, and the year in which he visited the north coast of Spitsbergen was 1607, not 1608. Moreover, Hudson himself has given an account of the voyage and makes absolutely no mention of Hudson's Tutches. It would have been hardly possible indeed for him to visit Jan Mayen on his way home from Bear Island to the Thames." Wordie 1922, p. 182.

Citations

- ^ Butts 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Hunter, D. (2007). God's Mercies: rivalry, betrayal and the dream of discovery. Toronto: Doubleday. p. 12. ISBN 978-0385660587.

- ^ De Laet, J. (1625). Nieuvve wereldt, ofte, Beschrijvinghe van West-Indien (in Dutch). Leyden: Elzevier. p. 83. OCLC 65327738.

- ^ "Half Moon :: New Netherland Institute". www.newnetherlandinstitute.org. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Rink, O. A. (1986). Holland on the Hudson: an economic and social history of Dutch New York. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0801418662.

- ^ "Biography – Hudson, Henry – Volume I (1000–1700) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Howgego 2003.

- ^ Pennington, P. (1979). The Great Explorers. New York: Facts on File. p. 90.

- ^ Mancall 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Henry Hudson's entry in Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Butts 2009, p. 15.

- ^ a b Mancall 2009, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Asher 1860, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Conway 1906, pp. 23–30.

- ^ Purchas 1625, p. 24; Conway 1906, p. 53.

- ^ Hunter 2009, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Purchas 1625, p. 11.

- ^ Hacquebord 2004, p. 229.

- ^ Purchas 1625, pp. 82–89; Hacquebord 2004, pp. 230–231.

- ^ "Empire of the Bay: Henry Hudson". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Hunter 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Hunter 2009, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Hunter 2009, pp. 92–94.

- ^ Hunter 2009, p. 98; Juet 1609, entry of 19 July.

- ^ Hunter 2009, pp. 102–105; Juet 1609, entry of 25 July.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (4 September 2009). "New York's Coldest Case: A Murder 400 Years Old". The New York Times.

- ^ Nevius, Michelle and James, "New York's many 9/11 anniversaries: the Staten Island Peace Conference", Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, 8 September 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- ^ Juet 1609.

- ^ Collier, Edward Augustus (1914). A History of Old Kinderhook from Aboriginal Days to the Present Time. New York: G. P. Putnam's sons. pp. 2–7. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ Hunter 2009, p. 235.

- ^ Shorto 2004, p. 31.

- ^ "Henry Hudson: Definition & Discoveries". HISTORY. 6 June 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ a b Levine, Robert S., ed. (2017). Norton Anthology of American Literature. Vol. 1 (9th ed.). London: Norton. pp. 98–102. ISBN 978-0393935714.

- ^ "Thomas Button Searches for Remains of Henry Hudson". Trajan Publishing Corporation. 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ "The Aftermath of Hudson's Voyages and Related Notes". Ian Chadwick. 19 January 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Neatby, L. H. (1979) [1966]. "Hudson, Henry". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ a b Heinrich, Jeff (13 August 1989). "A secret etched in stony silence". Ottawa Citizen. p. C3. Retrieved 28 October 2023 – via newspaper.com.

- ^ Roobol, M.J. (2019) Franklin's Fate: An investigation into what happened to the lost 1845 expedition of Sir John Frankin. Conrad Press, 368 pp.

- ^ "Carving on Rock Henry Hudson, 1612?". Toronto Star. 21 September 1962. p. 21. Retrieved 28 October 2023 – via newspaper.com.

- ^ "Impact". Henry Hudson. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Henry Hudson | Biography & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 14 March 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

Bibliography

- Asher, G. M. (1860). Henry Hudson, the navigator: the original document in which his career is recorded. London: Hakluyt Society. OCLC 1083477542.

- Butts, E. (2009). Henry Hudson: New World Voyager. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1554884551.

- Conway, W. M. (1906). No Man's Land: a history of Spitsbergen from its discovery in 1596. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 665157586.

- Hacquebord, L. (2004). "The Jan Mayen Whaling Industry". Jan Mayen Island in Scientific Focus. By Skreslet, S. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. pp. 229–238. ISBN 978-1402029554.

- Howgego, Raymond John, ed. (2003). "Hudson, Henry". Encyclopedia of Exploration to 1800. Hordern House. pp. 523–525. ISBN 1875567364.

- Hunter, D. (2009). Half Moon: Henry Hudson and the voyage that redrew the map of the New World. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1596916807.

- Juet, Robert (1609). Juet's Journal of Hudson's 1609 Voyage (PDF). From the 1625 edition of Purchas His Pilgrimes; transcribed 2006 by Brea Barthel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- Mancall, Peter (2009). Fatal Journey: The Final Expedition of Henry Hudson, A Tale of Mutiny and Murder in the Arctic. New York: Basic Books. p. 303. ISBN 978-0465005116.

- Purchas, S. (1625). Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes: Contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Travells by Englishmen and others. Volumes XIII and XIV (Reprint 1906 J. Maclehose and sons).

- Sandler, C. (2007). Henry Hudson: Dreams and Obsession. New York: Kensington Publishing Corp. p. 26.

- Shorto, R. (2004). The Island at the Center of the World: the epic story of Dutch Manhattan. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385503495.

- Wordie, J.M. (1922). "Jan Mayen Island", The Geographical Journal. Vol 59 (3).

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XII (9th ed.). 1881. pp. 332–333.

- Works about Henry Hudson at Open Library

- Works by or about Henry Hudson at the Internet Archive

- 16th-century English explorers

- 17th-century English explorers

- 1560s births

- 1610s deaths

- 1610s missing person cases

- Dutch East India Company people

- English explorers of North America

- English navigators

- Sailors from London

- Explorers of Canada

- Explorers of Svalbard

- British explorers of the Arctic

- Explorers of the United States

- Lost explorers

- Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada)

- Sailors on ships of the Dutch East India Company

- Muscovy Company