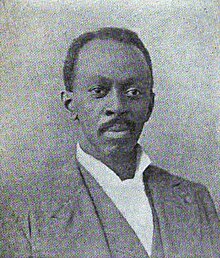

Richard R. Wright

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

Richard Robert Wright Sr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth | |

| In office 1891–1921 | |

| Succeeded by | Cyrus G. Wiley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 16, 1855[1] Dalton, Georgia, U.S.[1] |

| Died | July 2, 1947 (aged 92)[2] Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Spouse | Lydia Elizabeth (Howard) Wright |

| Children | 9, including Richard Robert Jr. |

| Alma mater | Atlanta University[1] The Wharton School[1] |

| Profession | Military officer, educator, banker |

| Military service | |

| Rank | Major |

| Unit | United States Volunteers |

Richard Robert Wright Sr. (May 16, 1855 – July 2, 1947) was an American military officer, educator and college president, politician, civil rights advocate and banking entrepreneur. Among his many accomplishments, he founded a high school, a college, and a bank. He also founded the National Freedom Day Association in 1941.[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Wright was born into slavery on May 16, 1855, in a log cabin six miles from Dalton, Georgia.[1][3]

After emancipation in 1865, Wright's mother moved with her son from Dalton to Cuthbert, Georgia. He attended the Storrs School, which developed by the late 1870s as Atlanta University, a historically black college or university. Today it is known as Clark Atlanta University, following a merger. The school had a reputation among freedmen as a place for their children to be educated.[4]

While visiting the school, retired Union General Oliver Otis Howard asked students what message he should take to the North. The young Wright reportedly told him, "Sir, tell them we are rising." That exchange inspired a once-famous poem by John Greenleaf Whittier, "Howard at Atlanta".[4][5]

The Storrs School was one of many academic schools for freedmen's children founded by the American Missionary Association (AMA) in the South. Wright was valedictorian at the first commencement ceremony in 1876.[3]

Career

[edit]Republican politics

[edit]Wright joined the Republican Party and became active in its politics. Blacks worked to resist white Democratic efforts to disrupt their organizing and suppress their votes.

There were also tensions within the party. In 1890, Emanuel K. Love and Wright were in a dispute with William White, Judson Lyons, Henry A. Rucker, and especially John H. Deveaux, who was in control of Georgia's Republic Party machinery. At the time, the party was dominated by African Americans. The dispute centered around leadership of the party district nomination conventions. Lyons, Rucker, and Deveaux were all supported by patronage of Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Institute. They were identified with light-skinned elites of the state, some of whose families had been free people of color, free for generations before the Civil War. Love, Wright (and Charles T. Walker) represented a "black" or "darker-skinned" faction. Skin color and assumptions about economic class were not as important as political allegiance and ideology.[6]

In 1896, Alfred Eliab Buck was the leader of the Georgia Republican Party. Buck was the president of the Republican State Convention in late April and presided over the election of delegates to the 1896 Republican National Convention. When dispute arose, Buck attempted to preempt by passing a "harmony" slate of delegates outside of standard procedure. However, the slate did not include Wright, who had widespread support among party members.[7]

When the convention erupted in protest, a representative of Buck's tried to adjourn the meeting, and the Buck faction left the hall. The Wright faction remained. Wright's friend, Emanuel K. Love, took the chair. A new slate of delegates was elected, including Love and Buck (but not Wright).[7] Wright never did win a seat as a delegate, but he attended the national party convention as an alternate.[8]

Military career

[edit]In August 1898, President William McKinley appointed Wright as a major and paymaster of United States Volunteers in the United States Army. He was the first African American to serve as a U.S. Army paymaster. During the Spanish–American War, he was the highest-ranking African-American officer.[5][9] He was honorably discharged in December of the same year.

Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth

[edit]The Second Morrill Land Grant Act of August 30, 1890 provided more land-grant funding to states, but also established federal oversight. It required that Southern and border states, which had segregated public schools, develop land grant colleges for black students in order to receive any funds under this program. Georgia was among the several states that had not done so. On November 26, 1890 the Georgia General Assembly passed legislation creating the Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth.[10]

In 1891, Wright was appointed as the first president of the Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth (now Savannah State University), the first public historically black college (HBCU) in the state. By October 1891, it was having classes in Savannah, Georgia, which became its permanent home. It started with five faculty and eight students, but rapidly attracted more.[3] It has since developed as Savannah State University, the oldest public HBCU in the state.

During the 1890s, Wright traveled to other colleges, including Tuskegee Institute, Hampton Institute, Girard College of Philadelphia, and the Hirsch School in New York, to document current trends in higher education. Based on his studies, he developed a curriculum at Georgia State College to include elements of the seven classical liberal arts, the "Talented Tenth" philosophy of W. E. B. Du Bois; Booker T. Washington’s vocational emphasis and self-reliance concepts, and the educational model of New England colleges. (He had graduated from Atlanta University, and was taught by graduates of Dartmouth College and Yale University).[3]

Wright was viewed as one of the leading figures of black higher education in America, and he conferred regularly with major educational leaders.[3] Visitors and lecturers to campus during his tenure as president included Mary McLeod Bethune, George Washington Carver, Walter Barnard Hill, Lucy Craft Laney, Mary Church Terrell, Booker T. Washington and Monroe Nathan Work.[3] U.S. presidents William McKinley and William Howard Taft also visited the campus and spoke to students in Peter W. Meldrim Hall.[3]

By the end of Wright's tenure as president, the college's enrollment had increased from the original eight students to more than 400. Additionally, he expanded the curriculum to include a normal division (for teacher training) and courses in agriculture and mechanical arts. He also provided four-year high-school subjects to prepare students who came from areas without such facilities, as was the case for many blacks from rural Georgia.[3]

Wright participated in the March 5, 1897 meeting to celebrate the memory of Frederick Douglass, who was an abolitionist and public intellectual. The group founded the American Negro Academy, led by Alexander Crummell.[11] From the founding of the organization until 1902, Wright remained active among the scholars, editors, and activists of this first major African-American learned society. Their work refuted racist scholarship, promoted black claims to individual, social, and political equality, and published the history and sociology of African-American life.[12]

Banker

[edit]After moving to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1921, Wright decided to open a bank. At the age of 67, he enrolled in the Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania to prepare for this venture.[5] He entered the business world in 1921, creating and leading Philadelphia's Citizens and Southern Bank and Trust Company at 1849 South Street. At the time, it was the only African-American-owned bank in the North and the first African-American trust company. He also founded the Negro Bankers Association, the first African-American banking association.[5]

Under his leadership, the bank withstood the Great Depression. When it was sold in 1957, more than a decade after Wright's death, it had assets of $5.5 million.[5]

Personal life

[edit]Wright married Lydia Elizabeth (née Howard). Together the couple had nine children, including Richard R. Wright Jr. He followed his father into an academic career.

Legacy

[edit]Civil rights leader

[edit]Richard Wright wrote a landmark letter to President Harry Truman describing the horrible mistreatment of Isaac Woodard, a black veteran who had been severely beaten and had his eyes gouged out by white policemen. As a result of this letter and advocacy by the NAACP about the case, President Truman asked his Attorney General, Tom Clark, to investigate. Clark brought a federal case against the police and sheriff who abused Woodard, but the all-white jury acquitted them. Georgia had passed an amendment in 1908 that essentially disenfranchised black voters; this absence from the voter rolls also resulted in their exclusion from juries.

Wright and others, including white liberals, were outraged, and they advocated for a federal civil-rights commission. Agreeing with this, Truman formed a committee on civil rights. It made far-reaching and prescient recommendations, including that there should be a permanent civil rights division in the Justice Department and that the entire executive branch of the federal government should be desegregated. Some agencies had established segregation in their facilities in the early 20th century under President Woodrow Wilson, who was influenced by his own background in the South and by Southern members of his cabinet. The military was still segregated, although blacks and other minorities had been arguing since World War I to end this, especially during World War II.

As a result, Truman ordered the desegregation of all branches of the military. The U.S. military has remained desegregated ever since.

Family legacy

[edit]In June 1898, Wright's son Richard R. Wright Jr. received the first baccalaureate degree awarded by Georgia State Industrial College. Wright Jr. was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania, having studied in the new field of sociology. He became a professor and later president of Wilberforce University in Ohio. He also was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent black denomination in the United States. Wright Jr. became a bishop in the AME Church.[3]

One of Richard Jr's daughters, Dr. Ruth Wright Hayre, also earned a Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania. They were the first African-American father and daughter to do so. Dr. Ruth Wright Hayre became the first full-time African-American teacher in the Philadelphia public-school system. She rose to become an administrator and high-school principal. After being elected to the Philadelphia Board of Education, she served as its first female president.

At the age of 80, she established the "Tell Them We Are Rising" program, promising to pay college tuition for 116 sixth-graders in two poor North Philadelphia schools if they completed high school. Her story was chronicled in her book Tell Them We Are Rising: A Memoir of Faith in Education, published in 1997, the year before she died.[4]

National Freedom Day

[edit]In 1941, Wright invited national and local leaders to meet in Philadelphia to formulate plans to set aside February 1 each year to memorialize the anniversary of the 1865 signing by President Abraham Lincoln of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which freed all U.S. slaves. They formed the National Freedom Day Association.[1]

One year after Wright's death in 1947, both houses of the U.S. Congress passed a bill to make February 1 National Freedom Day. The holiday proclamation was signed into law on June 30, 1948, by President Harry Truman. It was the forerunner to Black History Day and later Black History Month, officially recognized in 1976, though begun by Carter G. Woodson in 1926.[5][13]

Suggested reading

[edit]- Elmore, Charles J. (1996), Richard R. Wright Sr. at GSIC, 1891–1921: A Protean Force for the Social Uplift and Higher Education of Black Americans, Savannah, Georgia: privately printed.

- Hall, Clyde W. (1991), One Hundred Years of Educating at Savannah State College, 1890–1990, East Peoria, Ill.: Versa Press.

- Patton, June O. (1996), "'And the Truth Shall Make You Free': Richard Robert Wright Sr., Black Intellectual and Iconoclast, 1877–1897", The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 81.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Pennsylvania: Life and Times of Major Richard Robert Wright Sr. and the National Freedom Day Association". Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ Kranz, Rachel (2004). African-American Business Leaders and Entrepreneurs. Infobase Publishing. p. 302. ISBN 9781438107790.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Savannah State University". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ^ a b c "African American Firsts Highlight Rich Legacy". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ a b c d e f "125 Influential People and Ideas: Richard Robert Wright Sr". Wharton Alumni Magazine. Archived from the original on February 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ Dittmer, John. Black Georgia in the Progressive Era, 1900-1920. University of Illinois Press, 1980. p92-93

- ^ a b Shadgett, Olive Hall. The Republican Party in Georgia: From Reconstruction Through 1900. University of Georgia Press, 2010. pp. 133-134

- ^ Republican national convention, St. Louis, June 16th to 18th, 1896. With a history of the Republican party and a survey of national politics since the party's foundation, etc., etc., Republican National Convention (11th : 1896 : Saint Louis, Mo.), page 179, accessed October 17, 2016 at https://archive.org/stream/republicannation00repurich#page/178/mode/2up

- ^ "Documenting the American South". Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ Mastrovita, Mandy (April 7, 2012). "Morrill Land-Grant Act Sesquicentennial". Blog of the Digital Library of Georgia (the DLG B). Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Seraile, William. Bruce Grit: The Black Nationalist Writings of John Edward Bruce. Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2003. p110-111

- ^ Alfred A. Moss. The American Negro Academy: Voice of the Talented Tenth. Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

- ^ "National Freedom Day: A Local Legacy". Retrieved 2007-08-30.