Rationing in the United States

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, or services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one person's allotted portion of the resources being distributed on a particular day or at a particular time.

Rationing in the United States was introduced in stages during World War II, with the last of the restrictions ending in June 1947.[1] In the wake of the 1973 Oil Crisis, gas stations across the country enacted different rationing policies and standby rationing plans were introduced.

World War I

[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2023) |

Although the United States did not have food rationing in World War I, it relied heavily on propaganda campaigns to persuade people to curb their food consumption. Propaganda was targeted disproportionally towards middle class white women and their organization provided some of the most substantial support to Hoover's program to limit consumption.[2] Women's groups, like the Women's committees of the State Council of Defense organized in a variety of ways to try to provide relief to the shortages. In Wisconsin, they organized to can and preserve the food that grew in the garden of unoccupied houses.[3] Some states also implemented their own programs to help conserve food which was limited due to the war. In Wisconsin, the Council of Defense asked wholesale bakers to sign a pledge guaranteeing they'd keep bread on the shelves for longer durations.[3]

World War II

[edit]

We discovered that the American people are basically honest and talk too much.

— A ration board member[4]: 136

In the summer of 1941, rationing in the United Kingdom increased because of military needs, and German attacks on shipping in the Battle of the Atlantic. The British government appealed to Americans to conserve food to help the UK. The Office of Price Administration (OPA) warned Americans of potential gasoline, steel, aluminum, and electricity shortages.[5] It believed that with factories converting to military production and consuming many critical supplies, rationing would become necessary if the country entered the war. The OPA established a rationing system after the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December.[4]: 133

Ration books, stamps, and tokens

[edit]

The work of issuing ration books and exchanging used stamps for certificates was handled by some 5,500 local ration boards of mostly volunteer workers selected by local officials. Many levels of rationing went into effect. Some items, such as sugar, were distributed evenly based on the number of people in a household. Other items, like gasoline or fuel oil, were rationed only to those who could justify a need. Restaurant owners and other merchants were accorded more availability, but had to collect ration stamps to restock their supplies. In exchange for used ration stamps, ration boards delivered certificates to restaurants and merchants to authorize procurement of more products.

Each ration stamp had a generic drawing of an airplane, gun, tank, aircraft carrier, ear of wheat, fruit, etc. and a serial number. Some stamps also had alphabetic lettering. The kind and amount of rationed commodities were not specified on most of the stamps and were not defined until later when local newspapers published, for example, that beginning on a specified date, one airplane stamp was required (in addition to cash) to buy one pair of shoes and one stamp number 30 from ration book four was required to buy five pounds of sugar. The commodity amounts changed from time to time depending on availability. Red stamps were used to ration meat and butter, and blue stamps were used to ration processed foods.

To enable making change for ration stamps, the government issued "red point" tokens to be given in change for red stamps, and "blue point" tokens in change for blue stamps. The red and blue tokens were about the size of dimes (16 millimetres (0.63 in)) and were made of thin compressed wood fiber material, because metals were in short supply.[6]

There was a black market in stamps. To prevent this, the OPA ordered vendors not to accept stamps that they themselves did not tear out of books. Buyers, however, circumvented this by saying (sometimes accurately, as the books were not well-made) that the stamps had "fallen out". In actuality, they may have acquired stamps from other family members or friends, or the black market.[7]

Most rationing restrictions ended in August 1945 except for sugar rationing, which lasted until 1947 in some parts of the country.[8][9]

Tires, gasoline, and automobiles

[edit]Tires were the first item to be rationed by the OPA, which ordered the temporary end of sales on 11 December 1941 while it created 7,500 unpaid, volunteer three-person tire ration boards around the country. By 5 January 1942 the boards were ready. Each received a monthly allotment of tires based on the number of local vehicle registrations, and allocated them to applicants based on OPA rules.[4]: 133 There was a shortage of natural rubber for tires since the Japanese quickly conquered the rubber-producing regions of Southeast Asia. Although synthetic rubber had been invented before the war, it had been unable to compete with natural rubber commercially, so the US did not have enough manufacturing capacity at the start of the war to replace the lost imports of natural rubber, moreover, wartime synthetic rubber was significantly inferior in quality to natural rubber. Throughout the war, rationing of gasoline was motivated by a desire to conserve rubber as much as by a desire to conserve gasoline.[10]

The War Production Board (WPB) ordered the temporary end of all civilian automobile sales on 1 January 1942, leaving dealers with one half million unsold cars. Ration boards grew in size as they began evaluating automobile sales in February (only certain professions, such as doctors and clergymen, qualified to purchase the remaining inventory of new automobiles), typewriters in March, and bicycles in May.[4]: 124, 133–135 Automobile factories stopped manufacturing civilian models by early February 1942 and converted to producing tanks, aircraft, weapons, and other military products, with the United States government as the only customer.[11]

A national speed limit of 35 miles per hour (56 km/h) was imposed to save fuel and rubber for tires.[10] Later that month volunteers again helped distribute gasoline cards in 17 Atlantic and Pacific Northwest states.[4]: 138

To get a classification and rationing stamps, one had to appear before a local War Price and Rationing Board which reported to the OPA. Each person in a household received a ration book, including babies and small children who qualified for canned milk not available to others. To receive a gasoline ration card, a person had to certify a need for gasoline and ownership of no more than five tires. All tires in excess of five per driver were confiscated by the government, because of rubber shortages.

An "A" sticker on a car was the lowest priority of gasoline rationing and entitled the car owner to 3 to 4 US gallons (11 to 15 L; 2.5 to 3.3 imp gal) of gasoline per week. "B" stickers were issued to workers in the military industry, entitling their holder to up to 8 US gallons (30 L; 6.7 imp gal) of gasoline per week. "C" stickers were granted to persons deemed very essential to the war effort, such as doctors. Motorcycles had D papers and motorcycle users who were essential to the war got "M" papers. "E" and "R" stickers applied to small and heavy highway machinery, respectively. "T" stickers were made available for truckers. Lastly, "X" stickers on cars entitled the holder to unlimited supplies and were the highest priority in the system. Clergy, police, firemen, and civil defense workers were in this category.[12] A scandal erupted when 200 Congressmen received these X stickers.[13] Referring to the lowest tier of this system, American motorists jokingly said that OPA stood for "Only a Puny A-Card."

As a result of the gasoline rationing, all forms of automobile racing, including the Indianapolis 500, were banned. Sightseeing driving was also banned. In some regions breaking the gas rationing was so prevalent that night courts were set up to supplement the number of violators caught; the first gasoline-ration night court was created at Pittsburgh's Fulton Building on May 26, 1943.[14]

With the pending capitulation of Japan, the printing of ration books for 1946 was halted by the OPA on August 13, 1945. It was thought that "even if Japan does not fold now, the war will certainly be over before the books can be used".[15] After just two days, on August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered, and World War II gas rationing was ended on the West Coast of the United States.[16][17]

From the time that the United States entered the war to the August 1945 Japanese surrender, there was a dramatic shift in behavior: Americans drove cars less, carpooled when they did drive, walked and used their bicycles more, and increased the use of public transportation. Between 1941 and 1944 the total amount of gas consumed from highway use in the United States dropped to 32 percent. The federal agency named the Office of Defense Transportation (ODT) was established during the war to focus on controlling domestic transportation and was responsible for collecting data, conducting research and analysis, setting goals for fuel consumption and helping determine rationing coupon values. ODT-imposed rationing of gasoline to civilians caused car owners to drive less, thus extending tire life and conserving fuel to maximize the oil and rubber available for military use.[18]

In January 1942 there was a study published by the Public Roads Administration that discovered that driving 35 mph (56 km/h) helped tires last four times as long than if the speed was 65 mph (105 km/h). In order to extend the lifespan of tires and reduce the use, the ODT contacted the governors of all the states to establish lower speed limits. In March of the same year to decrease the large amount of single occupied drivers, car sharing programs were encouraged for workplaces that had more than 100 employees from the ODT and the Highway Traffic Advisory Committee.[18]

Food and consumer goods

[edit]Civilians first received ration books—War Ration Book Number One, or the "Sugar Book"—on 4 May 1942,[19] through more than 100,000 schoolteachers, PTA groups, and other volunteers.[4]: 137

Sugar was the first consumer commodity rationed, with all sales ended on 27 April 1942 and resumed on 5 May with a ration of 1⁄2 pound (8 oz; 227 g) per person per week, half of normal consumption. Bakeries, ice cream makers, and other commercial users received rations of about 70% of normal usage.[19] Coffee was rationed nationally on 29 November 1942 to 1 pound (454 g) every five weeks, about half of normal consumption, in part because of German attacks on shipping from Brazil.[20]

As of 1 March 1942, dog food could no longer be sold in tin cans, and manufacturers switched to dehydrated versions. As of 1 April 1942, anyone wishing to purchase a new toothpaste tube, then made from metal, had to turn in an empty one.[4]: 129–130 By June 1942 companies also stopped manufacturing metal office furniture, radios, television sets, phonographs, refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, washing machines, and sewing machines for civilians.[4]: 118, 124, 126–127

By the end of 1942, ration coupons were used for nine other items:[4]: 138 typewriters, gasoline, bicycles, shoes, rubber footwear, silk, nylon, fuel oil, and stoves. Meat, lard, shortening and food oils, cheese, butter, margarine, processed foods (canned, bottled, and frozen), dried fruits, canned milk, firewood and coal, jams, jellies, and fruit butter were rationed by November 1943.[21] Many retailers welcomed rationing because they were already experiencing shortages of many items due to rumors and panics, such as flashlights and batteries after Pearl Harbor.[4]: 133 Ration Book Number Five is a very rare ration book, only issued to very few people.[citation needed]

Medicines

[edit]Scarce medicines such as penicillin were rationed by triage officers in the US military during World War II.[22] Civilian hospitals received only small amounts of penicillin during the war, because it was not mass-produced for civilian use until after the war. A triage panel at each hospital decided which patients would receive the penicillin.

Gasoline rationing in the 1970s

[edit]

Rationing policies were enacted in response to both the 1973 Oil Crisis and 1979 Oil Crisis and policies varied by states. In California, even-odd rationing systems were created which alternated which day even and odd numbered license plates could get gas.[23] Gas stations throughout the country shortened their hours and on some days only served emergency vehicles. These policies were often met with hostility from consumers. In Baltimore, it peaked in February 1974 with gas station lines up to 5 miles long and violent threats made towards gas station owners.[24]

After the 1973 embargo, debates began over the necessity of gas rationing and rotation plans. President Richard Nixon reacted by creating the Federal Energy Office (FEO) which created a rationing plan that involved printing out 4.8 billion rationing coupons that were to be distributed to driver's license holders with the availability of mass transit being taken into account.[25] In 1975, Congress passed the Energy Policy and Conservation Act which required that rationing plans pass congressional review. The next plan to be submitted was President Gerald Ford’s before leaving office in January 1977.[25]

After assuming the presidency, Jimmy Carter withdrew Ford’s plan citing issues with the efficiency and implementation of the plan.[25] These plans faced scrutiny from the Chamber of Commerce, who stated in 1979 that they “opposed any form of rationing or allocation as solutions to current or future energy problems”.[26] Throughout the country, rationing plans were a point of contention. One Gallup poll in 1979 found that 40% of Americans polled favored a rationing program that would require Americans to drive one fourth less.[27] Initially, Carter's proposed plan kept the part of Johnson's plan that called for gas to be equally distributed by drivers licenses.[25] This drew widespread criticism because it didn’t factor discrepancies in the amount of gas needed in different areas. This criticism caused Carter to amend the plan, basing the allocation instead around historic consumption.[28] Another amendment was added at the request of the Republican opposition which would require a twenty percent shortage for 30 days in order to enact the plan.[29] This plan based around historic consumption succeeded in the Senate 58 to 39, but failed in the House 159 to 246.[30] After this failure, the Carter administration negotiated with congress which culminated in the Emergency Energy Conservation Act being signed into law which made it so Congress wasn’t required to approve the plan and instead could only vote to disprove the plan.[31] On July 30, 1980, Carter's plan was enacted and the United States had a standby plan for rationing Gasoline based around historic consumption with provisions around special usage for certain industries and a white market.[32]

Gallery

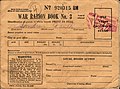

[edit]- World War II Ration Book, United States, ca 1943

-

USA Ration Book No. 3 circa 1943, front

-

Back of ration book

-

Fighter plane ration stamp

-

Artillery ration stamp

-

Tank ration stamp

-

Aircraft Carrier ration stamp

-

Basic mileage ration stamps for 1934 Plymouth

-

Back of mileage stamps

-

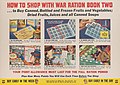

"How to Shop With Ration Book Two", 1943 poster

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Rationing". The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ Tunc, Tanfer Emin (2012). "Less Sugar, More Warships: Food as American Propaganda in the First World War". War in History. 19 (2): 199. doi:10.1177/0968344511433158. ISSN 0968-3445. JSTOR 26098429. S2CID 206609152.

- ^ a b Janik, Erika (2010). "Food Will Win the War: Food Conservation in World War I Wisconsin". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 93 (3): 17–27. ISSN 0043-6534. JSTOR 20699223.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kennett, Lee (1985). For the duration... : the United States goes to war, Pearl Harbor-1942. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-18239-4.

- ^ ""Creamless Days?" / The Pinch". Life. 1941-06-09. p. 38. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Joseph A. Lowande, U.S. Ration Currency & Tokens 1942-1945.

- ^ ".yahoo.com/, Voices, rationing for the war". Archived from the original on 2014-07-29. Retrieved 2014-07-22.

- ^ "World War II Rationing on the U.S. Homefront". Ames History Museum. Retrieved 2023-02-12.

- ^ "WWII Ration Books". History Media Center. University of Delaware. Retrieved 2023-02-12.

- ^ a b World War II on the Home Front

- ^ "U.S. Auto Plants are Cleared for War". Life. 16 February 1942. p. 19. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ fuel ration stickers Archived 2014-02-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Maddox, Robert James. The United States and World War II. Page 193

- ^ http://digital.library.pitt.edu/cgi-bin/chronology/chronology_driver.pl?q=&year=&month=5&day=26&start_line=0&searchtype=single&page=sim.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Associated Press, "Government Halts Printing Of Ration Books For 1946", The San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, California, Tuesday 14 August 1945, Volume 51, page 2.

- ^ A History of the Petroleum Administration for War, 1941-1945: U.S. Petroleum Administration for War, Washington, 1946. Washington: U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1946. Page 289

- ^ Loicano, Martin. National World War II Museum

- ^ a b Flamm, Bradley (March 2006). "Putting the Brakes on 'Non-Essential' Travel: 1940s Wartime Mobility, Prosperity, and the US Office of Defense". The Journal of Transport History. 27 (1): 71–92. doi:10.7227/TJTH.27.1.6. ISSN 0022-5266. S2CID 154113012.

- ^ a b "Sugar: U. S. consumers register for first ration books". Life. 1942-05-11. p. 19. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ "Coffee Rationing". Life. 1942-11-30. p. 64. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ rationed items Archived 2014-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kenneth V. Iverson and John C. Moskop, "Triage in Medicine, Part I", in Health Policy and Clinical Practice/Concepts, Volume 49, Num 3, March 2007, page 277, doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed,2006,05,019

- ^ Morrison, Patt. "The lines, the signs, the fights: In 1970s L.A., gas came at a premium". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "In the 1970s, it wasn't a pandemic that brought Baltimore to a standstill". Baltimore Sun. 2020-05-27. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ a b c d Caplinger, Christopher (1996). "The Politics of Trusteeship Governance: Jimmy Carter's Fight for a Standby Gasoline Rotationing Plan". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (3): 779. ISSN 0360-4918. JSTOR 27551631.

- ^ Standby gasoline rationing plan: narrative (Report). Office of Scientific and Technical Information (OSTI). 1979-02-01. doi:10.2172/6145884.

- ^ Farhar, Barbara; Weis, Patricia; Unseld, Charles; Burns, Barbara (June 1979). "Public Opinion About Energy: A Literature Review" (PDF). Solar Energy Research Institute: 227.

- ^ Caplinger, Christopher (1996). "The Politics of Trusteeship Governance: Jimmy Carter's Fight for a Standby Gasoline Rotationing Plan". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (3): 782. ISSN 0360-4918. JSTOR 27551631.

- ^ Weaver Jr., Warren (October 24, 1979). "Carter Empowered to Establish Plan for Gas Rationing". The New York Times.

- ^ Caplinger, Christopher (1996). "The Politics of Trusteeship Governance: Jimmy Carter's Fight for a Standby Gasoline Rotationing Plan". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (3): 784. ISSN 0360-4918. JSTOR 27551631.

- ^ Caplinger, Christopher (1996). "The Politics of Trusteeship Governance: Jimmy Carter's Fight for a Standby Gasoline Rotationing Plan". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (3): 787. ISSN 0360-4918. JSTOR 27551631.

- ^ Caplinger, Christopher (1996). "The Politics of Trusteeship Governance: Jimmy Carter's Fight for a Standby Gasoline Rotationing Plan". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (3): 788. ISSN 0360-4918. JSTOR 27551631.

External links

[edit]- What's Happened to Sugar? - 1945 film from the Office of Price Administration that explains why sugar rationing had to continue after the end of the war

- Ration Coupons on the Home Front, 1942-1945 - Duke University Libraries Digital Collections

- World War II Rationing on the U.S. homefront, illustrated - Ames Historical Society

- Links to 1940s newspaper clippings on rationing, primarily World War II War Ration Books - Genealogy Today

- Tax Rationing

- Recipe for Victory:Food and Cooking in Wartime

- Point Rationing of Foods - An animated illustration of the World War II point rationing system.