Building Act 1774

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An act for the further and better regulation of buildings and party-walls; and for the more effectually preventing mischiefs by fire within the cities of London and Westminster, and the liberties thereof, and other the parishes, precincts, and places, within the weekly bills of mortality, the parishes of Saint Mary-le-bon, Paddington, Saint Pancras, and Saint Luke at Chelsea, in the county of Middlesex; and for indemnifying, under certain conditions, builders and other persons against the penalties to which they are or may be liable for erecting buildings within the limits aforesaid contrary to law. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 14 Geo. 3. c. 78 |

| Introduced by | Robert Taylor and James Adam |

| Other legislation | |

| Amended by | |

| Repealed by |

|

Status: Partially repealed | |

| Text of the Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act 1774 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk. | |

The Building Act 1774 (formally known as the Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act 1774) was an Act passed in 1774 by the Parliament of Great Britain to consolidate earlier legislation and to regulate the design and construction of new buildings in London. The provisions of the Act regulated the design of new buildings erected in London and elsewhere in Great Britain and Ireland in the late Georgian period.

The 1774 Act standardised the quality and construction of buildings and made the exterior of a building as fire-proof as possible, by restricting any superfluous exterior timber ornamentation except for door frames and shop fronts. The Act placed buildings into classes or "rates" defined by size and value, with a code of structural requirements for the foundations and external and party walls for each of the rates. It mandated inspection of new buildings by building surveyors to ensure rules and regulations were applied. The Act also brought into being the first legislation that dealt with human life and escape, rather than just building safety, and made parishes responsible for permanent provision of working fire fighting equipment.

Professor Sir John Summerson, one of the leading British architectural historians of the 20th century, described it as "the great Building Act of 1774, a milestone in the history of London 'improvement'".[1] It was the leading reason for the appearance of the many Georgian houses, terraces and squares which remain important features of some parts of London and other cities and towns within the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland and elsewhere.[2]

Background

[edit]After the Great Fire of London of 1666, it was realised how much the traditional construction of buildings had aided the spread of the fire, with the close proximity of buildings and the incendiary nature of building material such as timber and thatch fuelling the fire.[3] Several Acts of Parliament over the next century attempted to improve building regulations:

- Rebuilding of London Act 1666 (18 & 19 Cha. 2. c. 8), also known as the London Building Act, determined that street widths, as well as the heights of houses, were regulated and brick construction was prescribed. Timber-framed buildings were forbidden. There could be no projections or jetties over the streets, because they allowed fire to leap from house to house. The intention was to make the street into an effective firebreak

- Mischiefs by Fire Act 1707 (6 Ann. c. 31) stipulated that wooden roofs had to be surrounded by a stone parapet

- Mischiefs by Fire Act 1708 (7 Ann. c. 17), also known as the London Building Act 1708, stipulated that window wooden frames should no longer be flush with the walls, but recessed

- Mischiefs by Fire Act 1724 (11 Geo. 1. c. 28)

- London Streets, City Act 1759 (33 Geo. 2. c. 30)

- Better Regulating of Buildings etc. Act 1764 (4 Geo. 3. c. 14)

- London Widening of Passages, etc. Act 1766 (6 Geo. 3. c. 27)

- Metropolitan Buildings Act 1772 (12 Geo. 3. c. 73), relating to party wall construction

These previous Acts had mostly failed due to the lack of enforcement.[4] The Building Act 1774 replaced, consolidated, improved and enforced these previous Acts.[5]

The new Act was drafted by the architects Robert Taylor and George Dance the Younger, who was then Clerk of the City Works.[Note 1] Its aims included:[1]

- Making the exterior of ordinary houses as nearly incombustible as possible

- Preventing slipshod construction of party walls

- Preventing disputes between adjoining owners of party walls

The Bill was submitted to the House of Commons in February 1774 by Robert Taylor and James Adam as "Joint Architects to H. M. Works", "on behalf of the Builders of London and Westminster", who found the existing legislation confusing and out of date.[6]

Title, short title and popular names

[edit]Acts passed by the Parliament of Great Britain did not originally have short titles; the Building Act 1774 was uniquely identified as 14 Geo. 3. c. 78. The long title of the Act is:[5]

"An act for the further and better regulation of buildings and party-walls; and for the more effectually preventing mischiefs by fire within the cities of London and Westminster, and the liberties thereof, and other the parishes, precincts, and places, within the weekly bills of mortality, the parishes of Saint Mary-le-bon, Paddington, Saint Pancras, and Saint Luke at Chelsea, in the county of Middlesex; and for indemnifying, under certain conditions, builders and other persons against the penalties to which they are or may be liable for erecting buildings within the limits aforesaid contrary to law."

The Short Titles Act 1896 (59 & 60 Vict. c. 14), Schedule 1, gave the 1774 Act the short title the Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act 1774, but it is more widely referred to as the Building Act 1774.[7] It is also known as the London Building Act 1774 and the Building Act of London 1774, and has been informally described as the Great Building Act 1774,[1] the Great Codifying Act 1774,[8] and the Black Act 1774 (not to be confused with the Black Act 1723).[9][10]

Main provisions

[edit]Building rates

[edit]In order to lay down hard and fast, standardised rules of construction it was necessary to categorise London buildings into separate classes or "rates". Each rate had to conform to its own structural code for foundations, thicknesses of external and party walls, and the positions of windows in outside walls. For all rates, the 1774 Act stipulated that all external window joinery was hidden behind the outer skin of masonry, as a precaution against fire. It also regulated the construction of hearths and chimneys.

The Act determined seven types of building construction graded by ground area occupied and value.[Note 2][11][12] The four rates applicable to houses predicted the likely social class of their occupants.[13]

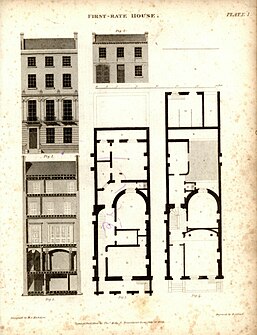

- A 'First Rate' house was valued at over £850, and occupied an area on the ground plan of more than nine "squares of building" (900 square feet (84 m2)). These houses were typically for the "nobility" or "gentry". The occupants would frequently not own the house, but would rent and use it as their townhouse[14] as a temporary alternative to their larger country house.

- A 'Second Rate' house was valued at between £300 and £850, and occupied an area on the ground plan of between five and nine "squares of building" (500–900 square feet (46–84 m2)). These houses were typically for "professional" men, "gentleman of good fortune", or "merchants", and might face notable streets or the River Thames.

- A 'Third Rate' house was smaller and valued at between £150 and £300, and occupied an area on the ground plan of between three and a half and nine "squares of building" (350–500 square feet (33–46 m2)). These houses were typically for "clerks", and faced principal streets.

- A “Fourth Rate” House was valued at less than £150, and occupied an area on the ground plan of less than three-and-a-half "squares of building" (350 square feet (33 m2)). These houses were typically for "mechanics" or "artisans", and would be found in minor streets.

All external woodwork, including ornament, was banished, except where it was necessary for shopfronts and doorcases. Bowed shop windows were made to draw in to a 10 inches (250 mm) or less projection. Window joinery which previous legislation had already pushed back from the wall face was now concealed in recesses to avoid the spread of fire.

- House Rates, as Defined by the 1774 Act - Example Designs (from Nicholson's The New Practical Builder, 1823)

-

First Rate House

-

Second Rate House

-

Third Rate House

-

Fourth Rate House

The Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Rates were for any other building, including cranehouses, windmills, watermills, and workshops. The Act included provisions stating a maximum floor area for warehouses.

Disputes

[edit]The Act regulated the responsibilities of the owners of party walls, and defined how disputes would be resolved.

Responsibilities of Surveyors

[edit]To address the past difficulties with enforcement, the Act created a statutory role for the surveyor. He had to survey any new building or wall being built, and was paid a fee by the master workman constructing the work. The surveyor had to swear an oath that he would ensure the rules and regulations of the Act were observed.[7] This led in 1844 to the role of "district surveyor".[15]

Parish Duties

[edit]

The Act stated that every parish must "have, and keep in good order and repair, and in some known and publick place within each parish, a large engine, and also an hand engine, to throw up water for the extinguishing of fires", and also pipes and firecocks with working supplies of water to supply these fire engines. In addition, the parish had to provide "in some known and publick place within each parish, three or more proper ladders of one, two and three story high, for assisting persons in houses on fire to escape therefrom". This was the first fire legislation to deal with human life and escape, rather than the safety of buildings alone.[17]

Insurance and accident

[edit]Before 1774 liability for fires in England was strict without exception. No excuse was permitted when an owner allowed a fire to spread to neighbouring properties, due to the danger of fire in crowded and largely wooden mediaeval towns and villages. The Act relaxed this liability by stipulating that no action should be taken against someone who caused a fire by accident. The Act also included measures to prevent deliberate fire setting in order to claim insurance

Adoption of the Act, and demand for the Third Rate House

[edit]

During the half-century or so after the 1774 Act came into force, building in brick or stone became standard in cities and towns, and houses of the second, third and fourth rate became standardised throughout the country.[18]

The rising population in London generated demand for housing, encouraging land owners to develop large tracts of land. The great majority of these developments were built speculatively: land owners improved their land by laying out roads and services, and then granted building leases on this land. Housing developers (landlords) would build "spec" houses on the improved land and generate an income from leaseholders by collecting rent.[19] A builder-speculator bought the leasehold of a site from the ground landlord and built the shell and roofed and floored it, usually with the bare internal walls roughly plastered out. This would be in accordance with the stipulations laid down by the 1774 Act and with the guidance of pattern books such as Peter Nicholson's The New Practical Builder (1823).[20] The first true occupiers of the house would then have the carcass finished to their own taste. Builders' guides were published, simplifying the statutory requirements.[21][22]

In 1821 the population of London had been 1.38 million. In the next fifty years it grew by a further million and the resultant need for housing, coming mainly from lower-middle and middle-class families – clerks, shopkeepers and other such tradespeople – was best met through the provision of terraced houses of medium size.[23] By far the greatest number of speculative houses built were of the third rate, whose exact dimensions were arrived at as a result of the areas defined in the Act. Also, J.C. Loudon suggested in The Suburban Gardener and Villa Companion (1838), "this technical classification of houses has been made by the British legislature, chiefly with a view to facilitate their assessment for taxes",[24] referring to taxes on windows,[Note 3] glass[Note 4] and brick,[Note 5] and houses were built to suit. Demand for the third rate house placed it at the forefront of the housing market; intended to offer the speculative builder the greatest economy, and the middle-class house buyer the greatest value, the terraced third rate house became, according to Loudon, the most numerous house type in early nineteenth-century London.[25]

Outside of London

[edit]Many of the regulations of the Act were subsequently applied outside of London in other cities and towns of Great Britain, especially in Bristol[26] and Liverpool,[27] and were also influential in developments in Edinburgh, Bath, Tunbridge Wells, Weymouth, Brighton, Margate, Buxton, Warwick, Newcastle upon Tyne and Cheltenham, and in Dublin and Newtown Pery in Ireland.[28][29] Some provisions of the Act became law in British colonies such as New Zealand.[30]

Criticism of the Act

[edit]

In Georgian London (1945), Summerson described how "the Act contributed largely to what the later Georgians and early Victorians conceived to be the inexpressible monotony of the typical London street, a monotony which certainly must, at one time, have been overpowering."[31] Whole streets and even neighbourhoods consisted of the same size of house. Ornament was discouraged, most woodwork was forbidden other than doors; window joinery was concealed behind recesses in the wallface. Summerson himself referred to a Georgian terrace, built in Dublin under the standards of the Act, as "simply one damned house after another".[32]

Victorians found the resulting houses and streets monotonous and the dimensional restraints tyrannical, and christened the Act "The Black Act of 1774",[33] although it was more likely the increasingly efficient capitalisation of building, not legislation, that was the main cause of this.[34] Benjamin Disraeli blamed the Act for "all those flat, dull spiritless streets all resembling each other, like a large family of plain children."[35] He also observed in his novel Tancred; or, the New Crusade (1847)[36] that:

"Though London is vast, it is very monotonous. All those new districts that have sprung up within the last half-century, the creatures of our commercial and colonial wealth, it is impossible to conceive anything more tame, more insipid, more uniform. Pancras is like Mary-le-bone, Mary-le-bone is like Paddington; all the streets resemble each other, you must read the names of the squares before you venture to knock at a door."

Gower Street in Bloomsbury, for example, was described by The Builder journal in 1887 as "one of the dullest, gloomiest thoroughfares in town [with its] monotonous elevations wholly unbroken or unrelieved",[37] and was referred to a decade later by historian Sir Laurence Gomme, in his commentary on London in the Reign of Victoria, as a "hideous monstrosity".[38]

The Victorians often did their best to destroy the scale and symmetry which were the hallmark of the Act, by breaking up the line of Georgian frontages and adorning their immaculate façades with terracotta and composition dressings.[39]

Apart from the rigid building prescriptions, the Act made no controls which related to matters of health. There were no controls on the amount of open space related to a dwelling, on the width of streets, on the height of buildings or on the height of rooms – even though these last two matters had had some tentative control under the earlier Rebuilding of London Act 1666. The 1774 Act did not legislate any limit on occupancy. Smaller houses which yielded low rents were increasingly shoddily built, and the combination of overcrowding and poor-quality housing led to a severe decline in general living conditions. The provisions were lacking in detail, especially in the areas of drainage and sanitary facilities, ventilation and damp proofing.[40]

Partial repeal

[edit]The 1774 Act was largely replaced by the Metropolitan Buildings Act 1844 (7 & 8 Vict. c. 84) and the Metropolitan Fire Brigade Act 1865 (28 & 29 Vict. c. 90),[41] leaving only sections 83 and 86 in force today, concerning buildings insurance and liability for reinstatement. Under Section 83, "to deter and hinder ill-minded persons from wilfully setting their house or houses, or other buildings, on fire, with a view of gaining to themselves the insurance money", the insurer could reinstate property if requested by an interested party, or if the insurer suspected fraud or arson. This power has been largely unused and may be unnecessary, and there has been discussion of whether it should be reformed.[42][43]

Importance of the Act

[edit]

As well as facilitating the enforcement of a structural code, the importance of the Building Act 1774 as explained by Summerson[44] was that:

"it confirmed a degree of standardisation in speculative building. This was inevitable; for the limitation of size and value set out in the rating tended to create optimum types from which there was no escape and within which very little variation was possible. Especially did the second, third and fourth rates of houses tend to become stereotyped. This was, in many ways, an excellent thing: it gave some degree of order and dignity to the later suburbs and incidentally laid down minimum standards for working-class urban housing which would have been decent if they had been accompanied by legislation against overcrowding."

The Act moved London away from its earlier chaotic and often mediaeval conditions, and ensured that whole city would be decent, handsome and orderly. It meant that, in an era when almost all construction was undertaken on speculative building leases, the landowner, the tenant and the community at large had a real guarantee of quality.[45]

Despite the later criticisms, it had a greater effect upon London than any other previous legislative measure, and had major influence in other cities and towns. It has been suggested that, by imposing a uniform image and a means to identify and control London before its subsequent immense expansion, the Act prepared the capital for its next imperial phase.[46]

The Act established over its long career a machinery for control which was well tried and tested. It established the origins of the role of District Surveyor[Note 6] and above all it acted as a model for subsequent regulations. It showed how a town or city council could obtain and administer legislation that would control the construction of buildings within a city in the interests of public safety and health.[40] The Building Acts in Bristol[Note 7][Note 8] were closely modelled on it and there were certain similarities in the Acts[Note 9] in Liverpool.[47] It established the principle that every parish had a duty to maintain equipment for fire fighting and rescue.

The new rating system led to the development of what are today perceived as grand and gorgeous terraces and squares in London and other cities and towns, creating simple and elegant uniformity which is much admired and reflected in the premiums paid when purchasing a Georgian property.[48] Most are now protected with listed building status.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ayres, James (1998). Building the Georgian City. Yale University Press: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. ISBN 978-0300075489.

- Building Act 1774 (1762). Text of the Act.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Casey, Christine (2005). Dublin. Buildings of Ireland. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10923-8.

- Cruickshank, Dan; Wyld, Peter (1975). London: The Art of Georgian Building. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0851393728.

- Gwynn, John (1766). London and Westminster Improved. London.

- Hobhouse, Hermione; Saunders, Ann (1989). Good and Proper Materials: The Fabric of London since the Great Fire. London Topographical Society. ISBN 978-0902087279.

- Knowles, Clifford Cyril; Pitt, Peter Hubert (1973). The History of Building Regulation in London, 1189-1972. London: Architectural Press. ISBN 978-0851392813.

- Ley, Anthony J. (1984). Building Control UK - An Historical Review (PDF). Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Ley, Anthony J. (2000). A History of Building Control in England and Wales 1840-1990. Coventry: RICS Building Services. ISBN 0-85406-672-1. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Loudon, John Claudius (1838). Suburban Gardener and Villa Companion. London. ISBN 9781107450592.

- Summerson, Sir John (1945). Georgian London (2003 ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0-30008988-0.

See also

[edit]- History of fire safety legislation in the United Kingdom

- Canning, Liverpool

- Clifton, Bristol

- Georgian Dublin

- Grainger Town, Newcastle upon Tyne

- New Town, Edinburgh, an 18th- and 19th-century development that contains some of the largest surviving examples of Georgian-style architecture and layout.

- Newtown Pery, Limerick

- The Georgian Group

Notes

[edit]- ^ Some works describe fellow architect and "improver" John Gwynn as a key figure in the introduction of the 1774 Act, but the source of this claim is elusive.

- ^ The Act simply specifies an undefined house "value". The Bank of England's Inflation Calculator gives the equivalence in prices between 1774 and 2020 as: £850 equivalent to £131,059; £300 equivalent to £46,256; £150 equivalent to £23,128. The landowner would normally grant a building licence to a builder and make an annual charge according to the location and the length of the frontage. According to the London County Council's Survey of London description of Ground Rent (referenced below), the cost per foot typically varied between a few shillings and a few guineas. The cost per foot was then multiplied by the total square footage of the footprint of the dwelling to set the ground rent and the house “rate”.

- ^ House Tax Act 1808 (48 Geo.3, c. 55) (Window Tax Act).

- ^ Excise Act 1825 (6 Geo. 4, c. 81).

- ^ Duties on Bricks and Tiles Act 1784 (24 Geo. 3 Sess. 2, c. 24); Duties on Bricks and Tiles Act 1785 (25 Geo. 3, c. 66); Duties on Bricks and Tiles Act 1794 (34 Geo. 3, c. 15); Excise Act 1803 (43 Geo. 3, c. 69); Excise Act 1805 (45 Geo. 3, c. 30); Excise (Ireland) Act 1826 (7 Geo. 4, c. 49).

- ^ The returns of the District Surveyors survive from 1774 (London Metropolitan Archives, MR/B, MBO).

- ^ Bristol Building Act 1778 (28 Geo. 3. c. 66) An Act for regulating Buildings and Party Walls within the City of Bristol.

- ^ Bristol Building Act 1840 (2 & 3 Vict. c. lxxvii) An Act for regulating Buildings and Party Walls within the City of Bristol and the widening and Improvement of Streets within the same.

- ^ Liverpool Building Act 1825 (6 Geo. 4. c. lxxv) An Act for the better regulation of Buildings within the Town of Liverpool.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Summerson 1945, p. 124.

- ^ Ayres 1998.

- ^ Porter, Stephen (2009). The Great Fire of London. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752450254.

- ^ Ley 1984, p. 1.

- ^ a b Text of the Act.

- ^ Summerson 1945, p. 407.

- ^ a b Knowles & Pitt 1973.

- ^ Wolford, Prof Sir William (March 1959). "The Tall Building in the Town". Official Architecture and Planning. 22 (3): 121–124. JSTOR 44128258. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Santo, Philip (2013). Inspections and Reports on Dwellings: Assessing Age. Taylor & Francis. p. 83.

- ^ Street, Emma (2011). Architectural Design and Regulation. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405179669.

- ^ Sheppard, F. H. W., ed. (1977). Survey of London: Volume 39, the Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 1 (General History): 'The Development of the Estate 1720-1785: Ground Rent'. London County Council. ISBN 9780485482393 – via British History Online.

- ^ Carrit, Dawn. "First Rate London Period Properties". Jackson-Stops.

- ^ Loudon 1838, pp. 35–36.

- ^ For a description of an 18th-century town house in England, for example, see Olsen, Kirsten, Daily Life in 18th-Century England, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, pp. 84–85. Also see Stewart, Rachel, The Town House in Georgian London, Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2009.

- ^ "The history of the London District Surveyors' Association" (PDF). London District Surveyors' Association. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Pyne, William Henry (1808–1811). Microcosm of London or, London in miniature. London: Rudolph Ackermann. ISBN 9780260155504. OL 7021107M.

- ^ Stephenson, Graham (2000). Sourcebook On Tort Law. Routledge Cavendish. ISBN 1-85941-587-3.

- ^ Cranfield, Ingrid (1997). Georgian House Style (1st ed.). Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. p. 44. ISBN 9780715312261.

- ^ Jackson, Neil (March 2016). Built to Sell: the Third Rate Speculative House in London. St John’s College, Oxford. (Unpublished).

- ^ Nicholson, Peter (1823). The New Practical Builder, And Workman's Companion (1st ed.). London: Thomas Kelly. ISBN 9781015929784.

- ^ Meymott, William (1774). An Abridgment Of Such Part Of The Building Act, (Passed In The Year, 1774,) As Will Be Useful To All Persons Who Have Either Freehold Or Leasehold Houses Or Buildings, Particularly To Surveyors, Builders, Carpenters, Bricklayers, &c (PDF). ISBN 9781385768693.

- ^ Elsam, Richard (1825). The Practical Builder's Price-Book. London: Thomas Kelly. ISBN 9781179722979.

- ^ Sheppard, Francis (1971). London 1808-1870: The Infernal Wen. University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780520018471.

- ^ Loudon 1838, p. 36.

- ^ Loudon 1838, p. 35.

- ^ Ley 2000, pp. 2–5.

- ^ Ley 2000, pp. 2, 5–6.

- ^ Girouard, Mark (30 April 990). The English Town: A History of Urban Life (1st ed.). Yale University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0300046359.

- ^ Iredale, David; Barrett, John (1 March 2002). Discovering Your Old House (4th ed.). Shire Publications. pp. 51, 144. ISBN 978-0747804987.

- ^ "Repeal of Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act 1774". New Zealand Legislation. New Zealand Government. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Summerson 1945, p. 126.

- ^ Casey 2005, p. 76.

- ^ Summerson 1945, p. 127.

- ^ Temple, Philip, ed. (2008). Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. London County Council. ISBN 9780300139372 – via British History Online.

- ^ Tambling, Jeremy (2008). Going Astray: Dickens and London (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 978-1405899871. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ Disraeli, Benjamin (1847). Tancred; or, the New Crusade. p. Chapter XVI. ISBN 9781973741718.

- ^ "Gower-street". The Builder. 52: 143. 22 January 1887. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Gomme, Sir George Laurence (1898). London in the Reign of Victoria (1837-1897). Chicago & New York: Herbert S. Stone & Company. p. 138.

- ^ Jenkins, Simon (1975). Landlords to London: The story of a Capital and its growth. London: Constable and Company Ltd. p. 167. ISBN 0-09-460150-X.

- ^ a b Ley 2000, p. 2.

- ^ "Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act 1774: Table of contents". Legislation.gov.uk. HM Government. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Reforming Insurance Contract Law, Introductory Paper. Section 83 of the Fires Prevention (Metropolis) Act 1774: should it be reformed?" (PDF). Law Commission. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Liability For Fire Cases". LawTeacher. All Answers Ltd. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Summerson 1945, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Jenkins, Simon (1975). Landlords to London: The Story of a Capital and Its Growth. London: Constable and Company Ltd. p. 167. ISBN 009460150X.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter (2000). London: The Biography. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 519. ISBN 0099422581.

- ^ Harper, Roger Henley. "The Evolution of the English Building Regulations 1840-1914 (D. Phil. Thesis)" (PDF). White Rose eTheses Online. Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Kelly, John (6 September 2013). "Which era of house do people like best?". BBC News.

- Construction law in the United Kingdom

- Great Britain Acts of Parliament 1774

- Legal history of England

- Legal history of the United Kingdom

- Laws in the United Kingdom

- Fire prevention

- Health and safety in the United Kingdom

- Georgian architecture

- Architectural styles

- British architectural history

- 18th-century architecture in the United Kingdom

- 19th-century architecture