Quinque compilationes antiquae

The Quinque compilationes antiquae[a] is a set of five collections of twelfth and thirteenth century decretals (specifically extravagantes)[3] totalling between 1,971[4] and 2,139 chapters.[5][6]

Content

[edit]Compilatio prima

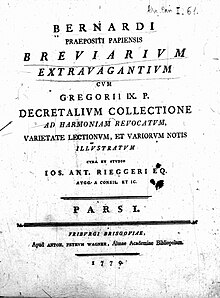

[edit]The first collection, the Compilatio prima,[4][7] was originally titled Breviarium extravagantium[b] (due to the fact that its decretals were not found in the Decretum Gratiani) and compiled by Bernardus Papiensis between 1189 and 1191,[8] making it the first non-anonymous collection of decretals.[9] Much of Bernardus' work collects decretals by Pope Alexander III, in addition to three decretals by Pope Gregory VIII and another three by Pope Clement III.[10]

Bernardus was the earliest known person to have published a systematically organised compilation of decretals on the jus novum,[11] although the Breviarium extravagantium was not his first attempt; around ten years prior, he had collected some ninety-five decretals in a manuscript titled Collectio Parisiensis secunda.[8]

The Compilatio prima introduced the five-book scheme (categorised according to the general subjects of "judge", "trial", "clergy", "marriage", and "crime") that was adopted by the other four collections in the Quinque compilationes and almost all other later decretal collections to boot.[1][10] Like the other collections in the Quinque compilationes, the Compilatio prima also contains a preface and is assigned chapters with various canons.[1]

Compilatio secunda

[edit]The second collection, the Compilatio secunda, was compiled by John Galensis and contains decretals by Pope Clement III, Pope Celestine III, Pope Alexander II, and Pope Lucius II.[12][13] Despite the fact that it was compiled shortly after the third collection, between 1210 and 1212,[13] the Compilatio secunda was so named because most of its decretals predate those found in the Compilatio tertia but postdate the ones in the Compilatio prima.[14]

Compilatio tertia

[edit]The third collection, Compilatio tertia, was compiled between late 1209 and early 1210 by a notary known as Petrus Beneventanus[15] or Pietro Collivacino.[13] It contains only decretals by Pope Innocent III, who expressed his approval of it and vouched for the authenticity of its contents, even though not all of them can be found in the papal registers.[16]

Compilatio quarto

[edit]The fourth collection, Compilatio quarto, was compiled by Johannes Teutonicus and contains canons passed by the Fourth Lateran Council alongside other decretals by Innocent III and 44 of his earlier letters.[13] The Compilatio quarto was presented to Innocent in 1215 but the pope refused to endorse it for unknown reasons.[17] Although initially disregarded by canonists, it was eventually published by Johannes sometime after Innocent's death.[18]

Compilatio quinta

[edit]In 1217, the recently-elected Pope Honorius III commissioned what would become the final collection in the Quinque compilationes; it was the first time that a pope had explicitly called for a decretal collection to be produced.[19] The Compilatio quinta was compiled by the archbishop of Bologna, Tancred, and published around 2 May 1226,[20] near the end of Honorius' pontificate.[6] Unlike the first four compilations, the Compilatio quinta contains secular legislation, specifically portions of Hac edictali lege, a statute written by Emperor Frederick II.[19]

Influence

[edit]Frequently cited by contemporary canonists,[13] the Quinque compilationes antiquae served as the "standard textbook" for the study of decretal law in the early thirteenth century.[21] Some 1,756 chapters' worth of content in the five collections were subsequently incorporated into the Liber extra decretalium by Raymond of Penyafort, which was commissioned by Pope Gregory IX in 1230 and completed in 1234.[6]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Drossbach 2022, p. 223.

- ^ Drossbach 2020, p. 50.

- ^ Johnson 2017, p. 406.

- ^ a b Duggan 2003, p. 869.

- ^ Rist 2015, p. 105.

- ^ a b c Drossbach 2022, p. 226.

- ^ Conte & Ryan 2014, p. 84.

- ^ a b Pennington 2008, p. 296.

- ^ Drossbach 2022, pp. 223–224.

- ^ a b Pennington 2008, p. 298.

- ^ Pennington 2008, p. 297.

- ^ Drossbach 2022, p. 224.

- ^ a b c d e Rist 2009, p. 122.

- ^ Pennington 2008, p. 312.

- ^ Pennington 2008, p. 309.

- ^ Pennington 2008, pp. 309–310.

- ^ Pennington 2008, p. 314.

- ^ Drossbach 2022, p. 225.

- ^ a b Pennington 2008, pp. 316–317.

- ^ Pennington 2008, p. 316.

- ^ Reno 2023, p. 308.

Works cited

[edit]- Conte, Emanuele; Ryan, Magnus (2014). "Codification in the Western Middle Ages". Diverging Paths?: The Shapes of Power and Institutions in Medieval Christendom and Islam. BRILL. pp. 75–97. doi:10.1163/9789004277878. ISBN 9789004277878.

- Drossbach, Gisela (2020). "Prefaces in Canon Law Books". In Brown-Grant, Rosalind; Carmassi, Patrizia; Drossbach, Gisela; Hedeman, Anne D.; Turner, Victoria; Ventura, Iolanda (eds.). Inscribing Knowledge in the Medieval Book: The Power of Paratexts. Medieval Institute Publications. pp. 46–55. doi:10.1515/9781501513329. ISBN 978-1-5015-1332-9. S2CID 241031452.

- Drossbach, Gisela (2022). "Decretals and Lawmaking". In Winroth, Anders; Wei, John C. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Medieval Canon Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. 208–229. doi:10.1017/9781139177221. hdl:10023/28800. ISBN 9781139177221.

- Duggan, C. (2003). "Quinque Compilationes Antiquae". New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11 (2 ed.). Gale. p. 869. ISBN 9780787640040.

- Johnson, Mark (2017). "Paul of Hungary's Summa de penitentia". In Sharp, Tristan; Cochelin, Isabelle; Dinkova-Bruun, Greti; Firey, Abigail; Silano, Giulio (eds.). From Learning to Love: Schools, Law, and Pastoral Care in the Middle Ages. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. pp. 402–418. doi:10.1515/9781771103817. ISBN 9780888448293.

- Pennington, Kenneth (2008). "Decretal Collections, 1190–1234". The History of Medieval Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140–1234: From Gratian to the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX. Catholic University of America Press. pp. 293–317. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2853s5.12. ISBN 9780813214917. JSTOR j.ctt2853s5.

- Reno, Edward A. (2023). "Gregory IX and the Liber Extra". Pope Gregory IX (1227–1241): Power and Authority. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 301–328. ISBN 9789048554607. JSTOR jj.809361.

- Rist, Rebecca (2009). The Papacy and Crusading in Europe, 1198–1245. Bloomsbury Publishing. doi:10.5040/9781472599186. ISBN 9781441140166.

- Rist, Rebecca (2015). Popes and Jews, 1095–1291. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198717980.001.0001. ISBN 9780191787430.