Quinnipiac University

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2015) |

| |

Former name | Connecticut College of Commerce (1929–1935) Junior College of Commerce (1935–1943; 1945–1951) Quinnipiac College (1951–2000) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Qui Transtulit Sustinet (Latin)[1] |

Motto in English | "He who transplants, sustains"[1] |

| Type | Private university |

| Established | 1929 |

| Accreditation | NECHE |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $674 million (2022)[2] |

| President | Judy D. Olian |

Academic staff | 350 full-time |

| Students | 9,744 (2020)[3] |

| Undergraduates | 6,841 (2020)[3] |

| Postgraduates | 2,903 (2020)[3] |

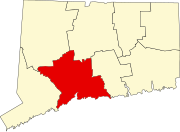

| Location | , , United States |

| Campus | Large Suburb[4], 600 acres (2.4 km2) |

| Other campuses | |

| Newspaper | The Quinnipiac Chronicle |

| Colors | Navy, gold, sky blue [5][6][7] |

| Nickname | Bobcats |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Boomer the Bobcat |

| Website | www |

| |

Quinnipiac University (/ˈkwɪnəˌpi.æk/ KWIH-nə-pee-ak)[8] is a private university in Hamden, Connecticut, United States. The university grants undergraduate, graduate, and professional degrees. It also hosts the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute.

History

[edit]What became Quinnipiac University was founded in 1929 by Samuel W. Tator,[9] a business professor and politician. Phillip Troup, a Yale College graduate, was another founder, and became its first president[9] until his death in 1939. Tator's wife, Irmagarde Tator, a Mount Holyoke College graduate, also played a major role in the fledgling institution's nurturing as its first bursar. Additional founders were E. Wight Bakke, who later became a professor of economics at Yale, and Robert R. Chamberlain, who headed a furniture company.[9]

The new institution was conceived in reaction to Northeastern University's abandonment of its New Haven, Connecticut, program at the onset of the Great Depression. Originally, it was located in New Haven and called the Connecticut College of Commerce. On opening its doors in 1929, it enrolled under 200, and its first graduating class comprised eight students. In 1935, the college changed its name to the Junior College of Commerce. In 1951, the institution was renamed Quinnipiac College, in honor of the Quinnipiac Indian tribe that once inhabited Greater New Haven. In 1952, the school relocated to a larger campus in New Haven, and also assumed administrative management of Larson College, a private women's college.

In 1966, Quinnipiac moved to its current campus in the Mount Carmel section of Hamden, Connecticut, at the foot of Sleeping Giant Park.[10] During the 1970s, Quinnipiac began to offer master's degrees.

Controversies

[edit]The university's official student newspaper is The Quinnipiac Chronicle.[11] In 2007 and 2008, Quinnipiac briefly drew national attention over the university's control over the Chronicle and other aspects of students' speech after the then-editor of the Chronicle openly criticized a university policy that forbade the newspaper from publishing news online before it was published in print. Manuel Carreiro, Quinnipiac's vice president and dean of students, allegedly threatened to fire Braff for disagreeing with school policies.[12][13] When former Chronicle staff members founded Quad News, an independent online paper, university officials allegedly instructed varsity coaches, staff and athletes not to speak to Quad News reporters.[14][15][16]

On July 21, 2010, a federal judge ruled that Quinnipiac violated Title IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by failing to provide equal treatment to women's athletic teams. The judge, Stefan Underhill, determined that Quinnipiac's decision to eliminate the women's volleyball team as well as its attempt to treat cheerleading as a competitive sport and its manipulation of reporting with regard to the numbers of male and female athletes amounted to unlawful discrimination against female students. Underhill ruled that competitive cheerleading was currently too underdeveloped and unorganized and then ordered that the school maintain its volleyball program for the 2010–11 season.[17][18]

In 2015, the university reached a settlement with the federal government over allegations that the university violated the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by "placing a student who had been diagnosed with depression on a mandatory medical leave of absence without first considering options for the student's continued enrollment." The university agreed to pay the former student over $32,000 to pay off her student loan and compensate her for "emotional distress, pain and suffering". The university also had agreed to implement a new policy of nondiscrimination against applicants or students on the basis of disability, examine changes that will allow students with mental health disabilities to participate in educational programs while seeking mental health treatment and provide additional ADA training for all staff.[19]

In 2020, two students reached a $2.5 million settlement with the federal government, alleging the shift in remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic devalued the promised educational experience. The students alleged the virtual environment deprived them of promised in-person instruction, campus events, and relationship building. The school denied these allegations, saying virtual instruction was in the best interest due to public health and safety concerns. Quinnipiac University students who attended the college during this time received a chunk of the $2.5 million payout.[20]

Campuses

[edit]

Quinnipiac University consists of three campuses: the Mount Carmel campus off of Mount Carmel Avenue in Hamden; the York Hill campus off of Sherman Avenue in Hamden, and the North Haven Campus in North Haven, just north of New Haven, Connecticut.

The oldest of these campuses is the Mount Carmel Campus, at the foot of Sleeping Giant State Park. The Arnold Bernhard Library, Carl Hansen Student Center, university administration, and many of the student residences are found on this campus. The campus area is a census-designated place (CDP); it first appeared as a CDP in the 2020 Census with a population of 3,639.[21]

The York Hill Campus, located on a hill about a half-mile from the Mount Carmel Campus, began with the development of the M&T Bank Arena (formerly People’s United Arena). In 2010 this was joined by a new student center as well as expanded parking and residence facilities as part of a $300 million expansion of the 250-acre (1.0 km2) campus.[22] York Hill is a "green" campus, making use of renewable energy and environmentally friendly resources, including one of the first major wind farms integrated into a university campus.[23]

For statistical reporting purposes, the Mount Carmel and York Hill campuses were listed together as the Quinnipiac University census-designated place prior to the 2020 census.[24]

In 2007, Quinnipiac acquired a 100-acre (0.40 km2) campus in North Haven, Connecticut, from Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield, and has been gradually converting it for use by graduate programs at the university.[25]

Academics

[edit]Quinnipiac offers 58 undergraduate majors and 22 graduate programs, including Juris Doctor and medical doctor programs. Its Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine admitted 60 students to its first class in 2013.[26] Quinnipiac University is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education.[27]

In 2021, 72.5% of undergraduate applicants were accepted with matriculated students having an average GPA of 3.47. Quinnipiac is "test optional" for standardized tests for undergraduate applicants, but encourages submitting SAT or ACT scores, or both. For those submitting scores, the average SAT score was 1175 and average ACT score was 26. Test scores are required for Quinnipiac's Accelerated Dual-Degree Bachelor's/JD (3+3) and Dual-Degree BS/MHS in Physician Assistant (4+27 months) programs, or for those that have been homeschooled.[28][29]

The university operates several media outlets, including a professionally run commercial radio station, WATX, founded by journalist and Quinnipiac professor Lou Adler. The university also operates a student-run FM radio station WQAQ, which concurrently streams on the Internet. An award-winning[30] student-run television station, Q30 Television, is streamed online. Also, a student-produced newspaper, the Chronicle, established in 1929, publishes 2,500 copies every Wednesday. Students also run a literary magazine, the Montage, a yearbook, the Summit, the Quinnipiac Bobcats Sports Network (an online sports-focused broadcast), and the Quinnipiac Barnacle[31] (a parody news organization). Unaffiliated with the school, but run by students, is also an online newspaper, the Quad News.[32]

Quinnipiac is home to one of the world's largest collections of art commemorating the Great Irish Famine. The collection is contained in Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum (Músaem An Ghorta Mhóir) just off the Mount Carmel Campus.[33]

Reputation and rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[34] | 215 |

| U.S. News & World Report[35] | 153 |

| Washington Monthly[36] | 283 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[37] | 261 |

Quinnipiac is 170th in the U.S. News & World Report 2024 rankings of national universities.[38] For 2021, U.S. News & World Report ranked the physician assistant school 15th nationwide, the law school 122nd, the medical school 94–122, and the business school 99–131.[39]

Zippia name Quinnipiac University as the No. 1 college in the United States for getting a job in 2021, but Zippia did not report salaries.[40]

Quinnipiac Polling Institute

[edit]Quinnipiac's polling institute receives national recognition for its independent surveys of residents throughout the United States. It conducts public opinion polls on politics and public policy as a public service as well as for academic research.[41] The poll has been cited by major news outlets throughout North America and Europe, including The Washington Post,[42] Fox News,[43] USA Today,[44] The New York Times,[45] CNN,[46] and Reuters.[47]

The polling operation began informally in 1988 in conjunction with a marketing class.[41] It became formal in 1994 when the university hired a CBS News analyst to assess the data being gained.[41] It subsequently focused on the Northeastern states, gradually expanding during presidential elections to cover swing states as well.[41] The institute receives funding from the university,[41] with its phone callers generally being work-study students or local residents. The polls have been rated highly by FiveThirtyEight for accuracy in predicting primary and general elections.[48] In 2017 Politico called the Quinnipiac poll "the most significant player among a number of schools that have established a national polling footprint."[49]

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[50] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 74% | ||

| Hispanic | 10% | ||

| Black | 4% | ||

| Asian | 4% | ||

| Foreign national | 3% | ||

| Other[a] | 3% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 16% | ||

| Affluent[c] | 84% | ||

Quinnipiac is home to seven fraternities and nine sororities.[51]

The National Panhellenic Conference is an umbrella organization which was created in 1902 for 26 women's sororities.

Athletics

[edit]The Quinnipiac Bobcats, previously the Quinnipiac Braves, comprise the school's athletic teams. They play in NCAA Division I in the Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference, except for the men's and women's ice hockey teams, which are part of ECAC Hockey, and the women's field hockey team, which joined Big East Conference starting with the 2016 season.[52]

There are 7 men's varsity sports and 14 women's varsity sports,[53] with no football team.[53] Men's varsity sports are baseball, basketball, cross country, ice hockey, lacrosse, soccer, and tennis. Women's varsity sports include acrobatics & tumbling, basketball, cross country, field hockey, golf, ice hockey, ice hockey, lacrosse, rugby, soccer, softball, tennis, indoor track & field, outdoor track & field, and volleyball.

The team with the largest following on campus and in the area is the men's ice hockey team under established coach Rand Pecknold,[54] which has been nationally ranked at times; during the 2009–2010 season they entered the top ten of the national polls for the first time.[55] The team was the number-one nationally ranked hockey program for parts of the 2012–2013 season, reaching the Frozen Four for the first time in the program's history. They advanced to the national championship, ultimately falling to rival Yale. They also advanced to the 2016 Frozen Four, losing to North Dakota in the national championship game. In 2023, the Bobcats defeated Minnesota 3-2, 10 seconds into overtime, to capture the 2023 NCAA Men's Ice Hockey Championship, the first NCAA National Championship for Quinnipiac in any sport.

The Quinnipiac women's ice hockey program had their most success in the 2009–10 NCAA Division I women's ice hockey season. Quinnipiac University added a women's golf and women's rugby team in the 2010–11 academic year, the women's golf team being successful and winning the MAAC Championship three years in a row. [53]

In the late 2000s the men's basketball team gained a greater following under new head coach Tom Moore, a disciple of UConn Huskies men's basketball coach Jim Calhoun.[54] Both men's and women's ice hockey and basketball teams play at the $52 million M&T Bank Arena, opened in 2007.[54] The women's lacrosse team has also been quite strong. Men's cross country captured 4 NEC titles in 5 years between 2004 and 2008. The athletics program has been under pressures common to other universities, and at the close of the 2008–2009 academic year, men's golf, men's outdoor track, and men's indoor track were dropped as a cost-cutting measure, although the last of these was restored (as a result of a Title IX suit.[56])

Notable alumni

[edit]- Lexie Adzija – ice hockey player

- Sam Anas – ice hockey player

- Matthew Batten – baseball player

- Bryce Van Brabant – ice hockey player

- Reid Cashman – ice hockey coach

- Ryan Cleckner – veteran activist

- Connor Clifton – ice hockey player

- Evan Conti – basketball player and coach

- John Delaney – baseball coach

- William D. Euille – former mayor of Alexandria, Virginia

- James Feldeine – basketball player

- Mary-Jane Foster – co-founder of a baseball team

- John Franklin - comedian

- Jared Grasso – basketball coach

- Freddy Hall – soccer goalkeeper

- Eric Hartzell – ice hockey player

- Dorit Kemsley – television actor[57]

- Themis Klarides – deputy minority leader of the Connecticut House of Representatives

- Chelsea Laden – television actor

- Murray Lender – former CEO of Lender's Bagels[58]

- Ilona Maher – rugby player

- Ann Marie McNamara – food safety pioneer

- Molly Qerim – sports television anchor

- Carley Shimkus – news reporter

- Devon Toews – ice hockey player

- Arnold Voketaitis – opera singer and teacher

- William C. Weldon – former CEO of Johnson & Johnson

- Turk Wendell – baseball player

- Cameron Young – basketball player

Notes

[edit]- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

[edit]- ^ a b QU Graphic Guide (PDF), Quinnipiac University, archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2014, retrieved July 9, 2013

- ^ As of March 7, 2022. U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2021 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY20 to FY21 (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ a b c As of October 15, 2020. "Student Consumer Information". Quinnipiac University. November 15, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "IPEDS – Quinnipiac University".

- ^ "Quinnipiac University Graphic Standards Manual 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "PMS Color Chart". Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "Quinnipiac — Story". Pentagram.

- ^ "Quinnipiac". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Catalog for Day and Evening Divisions, 1946–1947" (PDF). The Junior College of Commerce. 1946. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015.

- ^ "The Sleeping Giant Park Association". www.sgpa.org. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "About". The Quinnipiac Chronicle. August 4, 2023. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ Holtz, Jeff (December 2, 2007). "A Student Editor Finds Himself at the Center of the News". The New York Times. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ "The story of The Quad News, QU's 'forgotten,' independent newspaper". jessruderman.com. May 20, 2019. Archived from the original on February 15, 2024. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ Zapana, Victor (September 11, 2008). "No access to varsity sports for Quad News". Yale News.

- ^ Go, Allison (September 22, 2008). "The Quinnipiac Student Journalism Showdown". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ Walters, Erica (September 19, 2008). "Quinnipiac officials threaten to ban campus SPJ chapter after helping independent newspaper". Student Press Law Center. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved September 24, 2008.

- ^ "A Title IX decision that discounts competitive cheerleading as a sport at Quinnipiac University is strong evidence that it's time to change the law". ESPN. July 27, 2010. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ "QUINNIPIAC TITLE IX CASE: School must maintain women's volleyball program (document)". Nhregister.com. July 21, 2010. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ "Justice Department Settles Americans With Disabilties [sic] Act Case With Quinnipiac University". www.justice.gov. March 18, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ "Quinnipiac University reaches $2.5M settlement in remote learning tuition refund case". www.nhregister.com. December 12, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2024.

- ^ "Quinnipiac University CDP, Connecticut". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ "York Hill Campus Expansion | New York Construction | McGraw-Hill Construction". New York Construction. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ Prevost, Lisa (November 6, 2009). "School Colors: Green and Greener". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ "Quinnipiac University Census Designated Place". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ [1] Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Conntact.com". www.conntact.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011.

- ^ Connecticut Institutions – NECHE, New England Commission of Higher Education, retrieved May 26, 2021

- ^ "Undergraduate Admissions - Admission Requirements". qu.edu. Quinnipiac University. November 5, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Quinipiac Requirements for Admission". prepscholar.com. PrepScholar. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "College Media Association". College Media Association. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- ^ [2] Archived January 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [3] Archived February 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ireland's Great Hunger Museum, Quinnipiac University, 2012, archived from the original on February 8, 2013, retrieved April 28, 2013

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2023-2024 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 18, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. News Best Colleges Rankings - Quinnipiac University". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. News Graduate School Rankings – Quinnipiac University". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ "The Best College In Each State For Getting A Job 2022 – Zippia". Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Lapidos, Juliet (October 16, 2008). "What's With All the "Quinnipiac University" Polls? How an obscure school in Connecticut turned into a major opinion research center". Slate.

- ^ "Polls: Menendez Leads Kean in N.J. Race". The Washington Post. October 31, 2006. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ "Poll: Lieberman Leads Challenger Lamont in Connecticut Senate Race". Fox News. August 17, 2006.

- ^ "Quinnipiac Poll: Giuliani still leads GOP hopefuls, but by much less …". usatoday.com. June 25, 2007. Archived from the original on June 25, 2007. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Kapochunas, Rachel (July 13, 2007). "Poll Tests 'New York-New York-New York' Race in Ohio". The New York Times. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ Jeremy Diamond (February 3, 2015). "Poll: Clinton sweeps GOP foes save Bush tie in Florida". CNN. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ "Obama leads in four battleground states: poll". Reuters. June 26, 2008.

- ^ Silver, Nate (March 25, 2021). "Pollster Ratings - Quinnipiac University". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ Shepard, Steven (December 12, 2017). "The Poll That Built a University". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "College Scorecard: Quinnipiac University". United States Department of Education. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ "Verification | Quinnipiac University Connecticut". Quinnipiac.edu. August 17, 2015. Archived from the original on December 10, 2010. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ "BIG EAST Adds Liberty, Quinnipiac For Field Hockey" (Press release). Big East Conference. December 8, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c QuinnipiacBobcats.com. "Quinnipiac University's Official Athletics Site". Quinnipiac University. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ a b c Weinreb, Michael (December 26, 2007). "New Quinnipiac Coach Is Expected to Build a Winner". The New York Times. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- ^ QuinnipiacBobcats.com (November 23, 2009). "Men's Ice Hockey Ranked In Top 10 Nationally For First Time In Program History" (Press release). Quinnipiac University.[permanent dead link]

- ^ [4] Archived July 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Berg, Jenny (February 6, 2019). "Did Any of The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Go to College?". Bravo. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (March 22, 2012). "Murray Lender, Who Gave All America a Taste of Bagels, Dies at 81". The New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

External links

[edit]- Quinnipiac University

- Buildings and structures in Hamden, Connecticut

- Universities and colleges established in 1929

- Private universities and colleges in Connecticut

- North Haven, Connecticut

- Universities and colleges in New Haven County, Connecticut

- 1929 establishments in Connecticut

- Census-designated places in New Haven County, Connecticut

- Census-designated places in Connecticut