Queen of the Night aria

"Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen" ("Hell's vengeance boils in my heart"), commonly abbreviated "Der Hölle Rache", is an aria sung by the Queen of the Night, a coloratura soprano part, in the second act of Mozart's opera The Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte). It depicts a fit of vengeful rage in which the Queen of the Night places a knife into the hand of her daughter Pamina and exhorts her to assassinate Sarastro, the Queen's rival, else she will disown and curse Pamina.

Memorable with its upper register staccatos, the fast-paced and menacingly grandiose "Der Hölle Rache" is one of the most famous of all opera arias. This rage aria is often referred to as the Queen of the Night aria, although the Queen sings another distinguished aria earlier in the opera, "O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn".

Libretto

[edit]The German libretto of The Magic Flute was written by Emanuel Schikaneder, who also led the theatre troupe that premiered the work and created the role of Papageno.

Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen,

Tod und Verzweiflung flammet um mich her!

Fühlt nicht durch dich Sarastro Todesschmerzen,

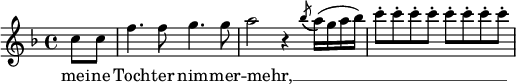

So bist du meine Tochter nimmermehr:

Verstoßen sei auf ewig,

Verlassen sei auf ewig,

Zertrümmert sei'n auf ewig

Alle Bande der Natur.

Wenn nicht durch dich Sarastro wird erblassen!

Hört, Rachegötter, hört der Mutter Schwur![1]

Hell's vengeance boils in my heart,

Death and despair blaze about me!

If Sarastro doesn't feel the pain of death through you,

Then you will not be my daughter anymore:

Disowned be you forever,

Abandoned be you forever,

Destroyed be forever

All the bonds of nature.

If not through you Sarastro will turn pale!

Hear, gods of revenge, hear the mother's oath!

Metrically, the text consists of a quatrain in iambic pentameter (unusual for this opera which is mostly in iambic tetrameter), followed by a quatrain in iambic trimeter, then a final pentameter couplet. The rhyme scheme is [ABAB][CCCD][ED].

Music

[edit]

The aria is written in D minor, and is scored for pairs of flutes, oboes, bassoons, horns in F, and trumpets, along with timpani and the string section. This is a larger orchestra than for "O zittre nicht" and comprises all the players from the opera as a whole, except the clarinets and trombones.

The aria is renowned as a demanding piece to perform well. The vocal range covers two octaves, from F4 to F6 and requires a very high tessitura, A4 to C6.[2]

Thomas Bauman has expressed particular admiration for one moment in the score. At the climax of the aria, the Queen sings the words "Hört, hört, hört!" solo, in alternation with loud chords from the orchestra. The first two syllables are sung to D and F, suggesting to the listener a third one on A, completing the D minor triad. But, as Bauman writes:

Mozart's masterstroke is the transformation he brought about by moving from the third degree to the flat sixth rather than to the fifth. ... No matter how often one hears this passage ... one is led by musical logic to expect, after D and F, A. But the Queen sings a terrifying B♭ instead.[3]

The effect is accompanied by unexpected Neapolitan harmony in the orchestra, with all the violins playing in unison high on the G string to intensify the sound.[4]

Performance history

[edit]

The first singer to perform the aria onstage was Mozart's sister-in-law Josepha Hofer, who at the time was 32. By all accounts, Hofer had an extraordinary upper register and an agile voice and apparently Mozart, being familiar with Hofer's vocal ability, wrote the two blockbuster arias to showcase it.

An anecdote from Mozart's time suggests that the composer himself was very impressed with his sister-in-law's performance. The story comes from an 1840 letter from composer Ignaz von Seyfried, and relates an event from the last night of Mozart's life—4 December 1791, five weeks into the opera's initial (very successful) run. According to Seyfried, the dying Mozart whispered the following to his wife Constanze:

Quiet, quiet! Hofer is just taking her top F; – now my sister-in-law is singing her second aria, 'Der Hölle Rache'; how strongly she strikes and holds the B-flat: 'Hört! hört! hört! der Mutter Schwur!'[5]

In modern times a number of notable sopranos have performed or recorded the aria. June Anderson sings it in the film Amadeus. The aria was also a favourite of the amateur soprano Florence Foster Jenkins.

A recording of the aria by Edda Moser, accompanied by the Bavarian State Opera under the baton of Wolfgang Sawallisch, is included in a collection of music from Earth on the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft.[6]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen", NMA

- ^ Aria details, Aria Database

- ^ Bauman, Thomas (1995) Opera and the Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 284.

- ^ NMA score

- ^ Quoted from Deutsch (1965, p. 556). For the B♭ to which Mozart referred, see discussion from Baumann above. The original German reads: "Still, still! Jetzt nimmt die Hofer das hohe F; – jetzt singt die Schwägerin ihre zweite Arie: 'Der Hölle Rache'; wie kräftig sie das B anschlägt und aushält: 'Hört! hört! hört! der Mutter Schwur!'". Source: "Die Verdienste des Herrn Schikaneder", Hamburger Abendblatt (3 January 1994) (in German)[dead link]

- ^ Golden Record – Music From Earth, Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Sources

- Deutsch, Otto Erich (1965). Mozart: A Documentary Biography. Stanford University Press].

External links

[edit]- Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen: Score in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe

- "Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen": from Die Zauberflöte, Mozart's autograph manuscript in the Berlin State Library

- Analysis, discussion: Rhiannon Giddens, Kathryn Lewek, Carolyn Abbate, Jan Swafford, Timothy Ferris; WQXR-FM, podcast at WNYC Studios (26:00)

- Edda Moser: "Der Hölle Rache" on YouTube

- Several recordings at Neue Mozart-Ausgabe