Qadiriyya wa Naqshbandiyya

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

Qadiriyya wa Naqshbandiyya (Arabic: قادرية و نقشبندية, lit. 'Qadirism and Naqshbandism') is a Sufi order which is a synthesis of the Qadiri and Naqshbandi orders of Sufism.[1] The Qadiriyya wa Naqshbandiyya Sufi order traces back through its chain of succession to Muhammad, through the Hanbali Islamic scholar Abdul Qadir Gilani and the Hanafi Islamic scholar Shah Baha al-Din Naqshband, combining both of their Sufi orders.[1][2] The order has a major presence in three countries, namely Pakistan, India, and Indonesia.[3][4]

Prominent members

[edit]- Hazrat Ishaan Khawand Mahmud (1563–1642), whose membership in the Naqshbandi order was allegedly foretold by Shah Baha al-Din Naqshband;[5] Baha al-Din Naqshband proclaimed the succession of his descendant Khawand Mahmud.[6]

- Imam Rabbani Ahmad Sirhindi (1564–1624), an immediate student of Baqi Billah. Ahmad Sirhindi was a member of the Naqshbandi, Qadiri, Chishti and Suhrawardi Sufi orders, although he preferred the Naqshbandi order.[7]

- Mohi al-Din Aurangzeb (1618–1707), an immediate student of Sayyid Mirza Nizamuddin Naqshbandi.[citation needed]

- Sayyid Mir Jan (1800–1901), Hazrat Ishaan and his family allegedly foretold his coming; Yasin Qasvari proclaimed Sayyid Mir Jan as a successor of Hazrat Ishaan and the promised "Khwaja of all Khwajas".[2]

- Ahmad Khatib al-Minangkabawi (1860–1915), an Indonesian Islamic scholar from the mid-19th century.[4]

History

[edit]Indian Subcontinent

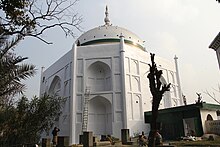

[edit]Khwaja Khawand Mahmud bin Sharifuddin al-Alavi, known by his followers as Hazrat Ishaan was directed by his Pir Ishaq Wali Dahbidi to spread Islam in Mughal India. His influence mostly remained in the Kashmir valley, whereupon Baqi Billah has expanded the order in other parts of India.[8] Mahmud is a significant Saint of the order as he is a direct blood descendant in the 7th generation of Baha al-Din Naqshband, the founder of the order[8] and his son in law Alauddin Atar.[9] It is because of this that Mahmud claims direct spiritual connection to his ancestor Baha al-Din.[8] Furthermore Mahmud had a significant amount of nobles as disciples, highlighting his popular influence in the Mughal Empire.[10] His main emphasis was to highlight orthodox Sunni teachings.[10] Mahmud's son Moinuddin lies buried in their Khanqah together with his wife who was the daughter of a Mughal Emperor. It is a pilgrimage site in which congregational prayers, known as "Khwaja Digar" are held in honor of Baha al-Din on his death anniversary the 3rd Rabi ul Awwal of the Islamic lunar calendar. This practice including the "Khatam Muazzamt" is a practice that goes back to Mahmud and his son Moinuddin[8] The Kashmiri population venerate Mahmud and his family as they have regarded them as the revivers of Islam in Kashmir.[3] Mahmud was succeeded by his son Moinuddin and their progeny until the line died out on the occasion of the martyrdom of the last Ishan Kamaluddin and his family members by the Shiite warlord Amir Khan Jawansher in the eighteenth century.[9] Moinuddin's successors were:[9]

- Bahauddin, son of Mahmud.

- Ahmad, son of Mahmud.

- Nizamuddin, son of Sharifudin, son of Moinuddin, who married a daughter of Aurangzeb.

- Nooruddin, son of Nizamuddin.

- Kamaluddin, son of Nooruddin, martyred by the Shiite warlord Amir Khan Jawansher.

It is said that Mahmud and his son Moinuddin stated that under their progeny there will come a son of them, who will revive the spiritual lineage and legacy of the family after a tragic incident, that was to be the martyrdom of family members in Srinagar. It is believed that this successor is Sayyid Mir Jan.[11][12]

Southeast Asia

[edit]Shaykh Ahmad Khatib was a prominent Islamic scholar from what is now Indonesia in the mid-19th century.[4] He was a member of the Qadiri Sufi order, but when he visited the cities of Makkah and Medina in the Ottoman Empire, he learnt the teachings of the Naqshbandi Sufi order, and very likely pledged allegiance to it.[4] Be cause the Qadiri order permits its Shaykhs to modify it, Shaykh Ahmad Khatib was able to synthesize the Qadiri and Naqshbandi Sufi orders together, and become a Shaykh of the Qadiriyya wa Naqshbandiyya Sufi order, and spread his teachings which became especially popular in Southeast Asia to his students.[4]

In what is now Indonesia, the members of the Sufi order in Banten and Lombok led rebellions against the Dutch East Indies at the end of 19th century.[13]

See also

[edit]- Qadiri Sufi order

- Naqshbandi Sufi order

- Sayyid Abdul Qadir Gilani

- Sayyid Baha al-Din Naqshband

- Mawaddat al-Qurba

- Sayyid Ali Akbar ibn Hasan al Askari

- Hazrat Ishaan

- Ishan (Title)

- Sayyid Moinuddin Hadi Naqshband

- Ziyarat Naqshband Saheb

- Sayyid Mir Jan

- Sayyid Mahmud Agha

- Sayyid Mir Fazlullah Agha

- Dakik Family

- Royal Sayyids

- Barakzai Dynasty

References

[edit]- ^ a b van Bruinessen, Martin (1994). Tarekat Naqsyabandiyah di Indonesia (in Indonesian). Bandung: Mizan. ISBN 979-433-000-0.

- ^ a b Tazkare Khwanadane Hazrat Eshan(Stammesverzeichnis der Hazrat Ishaan Kaste)(verfasst und geschriben von: Yasin Qasvari Naqshbandi Verlag: Talimat Naqshbandiyya in Lahore), p. 281

- ^ a b Shah, Sayid Ashraf (2021-12-06). Flower Garden: Posh-i-Chaman. Ashraf Fazili.

- ^ a b c d e "Pondok Pesantren SURYALAYA". www.suryalaya.org. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- ^ David Damrel in Forgotten grace: Khwaja Khawand Mahmud Naqshbandi in Central Asia and Mughal India, p. 67

- ^ David Damrel in Forgotten grace: Khwaja Khawand Mahmud Naqshbandi in Central Asia and Mughal India, p. 67

- ^ "Shaykh Ahmad al-Faruqi as-Sirhindi ق - Naqshbandi". naqshbandi.org. 2023-08-28. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- ^ a b c d Damrel, David William (1994). "Forgotten Grace: Khwaja Khawand Mahmud Naqshbandi in Central Asia and Mughal India". books.google.com. Retrieved 2022-09-29.

- ^ a b c Weismann, Itzchak (2007-06-25). The Naqshbandiyya: Orthodoxy and Activism in a Worldwide Sufi Tradition. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-35305-7.

- ^ a b Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ^ Sufi Sheikhs of Pakistan and Afghanistan

- ^ Nicholson, Reynold (2000). Kashf al-Mahjub of al-Hajvari. E. J. W. Gibb Memorial.

- ^ van Bruinessen, Martin (1994). Tarekat Naqsyabandiyah di Indonesia (in Indonesian). Bandung: Mizan. ISBN 979-433-000-0.