Psychobiotic

This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (December 2018) |  |

Psychobiotics is a term used in preliminary research to refer to live bacteria that, when ingested in appropriate amounts, might confer a mental health benefit by affecting microbiota of the host organism.[1] Whether bacteria might play a role in the gut-brain axis is under research. A 2020 literature review suggests that the consumption of psychobiotics could be considered as a viable option to restore mental health[2] although lacking randomized controlled trials on clear mental health outcomes in humans.[3][4]

Types

[edit]

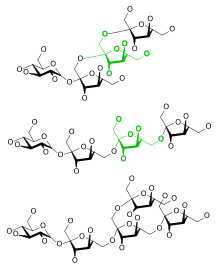

In experimental probiotic psychobiotics, the bacteria most commonly used are gram-positive bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus families, as these do not contain lipopolysaccharide chains, reducing the likelihood of an immunological response.[1] Prebiotics are substances, such as fructans and oligosaccharides, that induce the growth or activity of beneficial microorganisms, such as bacteria on being fermented in the gut.[1][5] Multiple bacterial species contained in a single probiotic broth is known as a polybiotic.[6]

Research

[edit]A 2021 review showed that treating anxiety in young people with psychobiotics had no significant effect.[7] There is a need for more diverse human studies, mainly because those that exist have contradictory outcomes.[3][4][7]

Species

[edit]

Several species of bacteria have been used in probiotic psychobiotic research:[6][8]

- Lactobacillus helveticus

- Bifidobacterium longum

- Lactobacillus casei

- Lactobacillus plantarum

- Lactobacillus acidophilus

- Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus

- Bifidobacterium breve

- Bifidobacterium infantis

- Streptococcus salivarius

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus

- Lactobacillus gasseri

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sarkar A, Lehto SM, Harty S, Dinan TG, Cryan JF, Burnet PW (November 2016). "Psychobiotics and the Manipulation of Bacteria-Gut-Brain Signals". Trends in Neurosciences. 39 (11): 763–81. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2016.09.002. PMC 5102282. PMID 27793434.

- ^ Del Toro-Barbosa, M.; Hurtado-Romero, A.; Garcia-Amezquita, L. E.; García-Cayuela, T. (2020). "Psychobiotics: Mechanisms of Action, Evaluation Methods and Effectiveness in Applications with Food Products". Nutrients. 12 (12): 3896. doi:10.3390/nu12123896. PMC 7767237. PMID 33352789.

- ^ a b Romijn AR, Rucklidge JJ (October 2015). "Systematic review of evidence to support the theory of psychobiotics". Nutrition Reviews. 73 (10): 675–93. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv025. PMID 26370263.

- ^ a b Liu B, He Y, Wang M, Liu J, Ju Y, Zhang Y, Liu T, Li L, Li Q (July 2018). "Efficacy of probiotics on anxiety-A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Depression and Anxiety. 35 (10): 935–45. doi:10.1002/da.22811. PMID 29995348. S2CID 51615532.

- ^ Hutkins RW, Krumbeck JA, Bindels LB, Cani PD, Fahey G, Goh YJ, Hamaker B, Martens EC, Mills DA, Rastal RA, Vaughan E, Sanders ME (February 2016). "Prebiotics: why definitions matter". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 37: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2015.09.001. PMC 4744122. PMID 26431716.

- ^ a b Bambury A, Sandhu K, Cryan JF, Dinan TG (December 2018). "Finding the needle in the haystack: systematic identification of psychobiotics". British Journal of Pharmacology. 175 (24): 4430–38. doi:10.1111/bph.14127. PMC 6255950. PMID 29243233.

- ^ a b Cohen Kadosh, Kathrin; Basso, Melissa; Knytl, Paul; Johnstone, Nicola; Lau, Jennifer Y. F.; Gibson, Glenn R. (2021-06-16). "Psychobiotic interventions for anxiety in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis, with youth consultation". Translational Psychiatry. 11 (1): 352. doi:10.1038/s41398-021-01422-7. ISSN 2158-3188. PMC 8206413. PMID 34131108.

- ^ Dinan TG, Stanton C, Cryan JF (November 2013). "Psychobiotics: a novel class of psychotropic". Biological Psychiatry. 74 (10): 720–26. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.001. PMID 23759244. S2CID 40059439.

Further reading

[edit]- Anderson, Scott C.; Cryan, John F.; Dinan, Ted (17 December 2019). The Psychobiotic Revolution (1 ed.). Random House US. ISBN 9781426219641.