Proliferative fasciitis and proliferative myositis

| Proliferative fasciitis and proliferative myositis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Histopathology of proliferative fasciitis or proliferative myositis | |

| Specialty | Dermatology, General surgery |

| Usual onset | Very rapid |

| Duration | Often regresses spontaneously within weeks of diagnosis |

| Treatment | symptomatic therapy, watchful waiting, surgical resection |

| Prognosis | Excellent |

| Frequency | Extremely rare |

Proliferative fasciitis and proliferative myositis (PF/PM) are rare benign soft tissue lesions (i.e. a damaged or unspecified abnormal change in a tissue) that increase in size over several weeks and often regress over the ensuing 1–3 months.[1] The lesions in PF/PM are typically obvious tumors or swellings. Historically, many studies had grouped the two descriptive forms of PF/PM as similar disorders with the exception that proliferative fasciitis occurs in subcutaneous tissues[2] while proliferative myositis occurs in muscle tissues.[3] In 2020, the World Health Organization agreed with this view and defined these lesions as virtually identical disorders termed proliferative fasciitis/proliferative myositis or proliferative fasciitis and proliferative myositis. The Organization also classified them as one of the various forms of the fibroblastic and myofibroblastic tumors.[4]

PF/PM lesions have been regarded as a tissue's self-limiting reaction to an injury or unidentified insult rather than an abnormal growth of a clone of neoplastic cells, that is, as a group of cells which share a common ancestry, have similar abnormalities in the expression and/or content of their genetic material, and often grow in a continuous and unrestrained manner.[5] However, a recent study has found a common genetic abnormality in some of the cells in most PF/FM tumors. This suggests that PF/PM are, in at least most cases, neoplastic but nonetheless self-limiting and/or spontaneously reversing disorders. That is, they are examples of "transient neoplasms." In all events, PF/PM lesions are benign tumor growths that do not metastasize.[6]

PF/PM lesions may grow at alarming rates,[3] exhibit abnormal histopathologies (e.g. high numbers and overcrowding of cells), and have other elements that are suggestive of a malignancy.[7] Consequently, they have been mistakenly diagnosed as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (also termed malignant fibrous histiocytoma), rhabdomyosarcoma,[1] or other types of sarcoma[8] and treated unnecessarily with aggressive measures used for such malignancies, e.g. wide surgical resection, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.[1][9] The majority of PF/PM lesions are successfully treated with strictly conservative and supportive measures.[6]

Presentation

[edit]PF/PM lesions occur primarily in middle-aged and older adults[6] (peak age of onset 50 to 55 years/old) with no appreciable differences in their incidences between males and females.[1] Only very rare cases have been reported in children and adolescents.[2] In up to 20% to 30% of cases, these lesions are apparently preceded by some sort of mechanical injury.[1] Individuals commonly present within 1–3 weeks[1] or, rarely, longer times (e.g. 3 months)[8] of noticing a rapidly growing, small (<5 cm. in size) mass or swelling in the subcutaneous tissues or muscles[1] of an extremity or, less commonly, the trunk wall, head, or neck areas.[6] Uncommonly, the lesions are ulcerated.[3] In rare cases, the lesions are extensive and highly disruptive, e.g. PF/PM has presented with lockjaw, i.e. a reduced ability to open the jaw due to a PF/PM lesion infiltrating and disrupting the function of the muscles of mastication (i.e. jaw-opening muscles).[1] PF/PM lesions may be associated with tenderness, pain,[6] and/or very rarely fever of unknown cause.[1] The lesions may be regressing at the time of diagnose or, in rare instances, spontaneously regress beginning immediately after being biopsied.[10] Very rarely, these lesions have evolved rapidly, compromised local blood flow,[3] and/or recurred at the site where they were removed by conservative local surgical excision. However, PF/MF lesions do not metastasize to distant tissues.[2]

Pathology

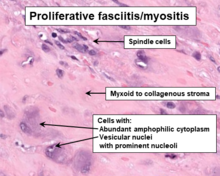

[edit]PF/PM lesions are poorly circumscribed masses[6] which on histopathological microscopic analyses consist of bland fibroblastic and myofibroblastic spindle-shaped cells[3] mixed with variable proportions of giant epithelioid ganglion cell-like cells.[6] These cells are in a myxoid (i.e. a clear, mucus-like substance which when prepared using a standard H&E staining method appears more blue or purple than the red color of normal tissues) to fibrous (i.e. high collagen fiber content) background[6] which may contain areas of necrosis (i.e. sites of dead cells).[2] Overall, the cells in these lesions are amphophilic or basophilic, may have vacuole-laden cytoplasm, are slowly multiplying based on their proliferative index, and lack atypical mitosis figures that might be suggestive of a malignancy. The presence of at least some giant epithelioid ganglion-like cells[10][6] within this histopathological background are necessary and definitive evidence that a swelling or tumor is a PF/PM. Compared to adult cases, pediatric cases of PF/PM lesions are often better delineated from normal tissue, are more cellar, have a greater frequency of necrosis sites,[2] contain diffuse sheets of epitheliod ganglion-like cell cells but lack a spindle-shaped cell component, and are lobulated.[6] The spindle-shaped cells, but not epithelioid ganglion-like cell cells, in proliferative myositis lesions express smooth muscle actin proteins.[8]

Genetics

[edit]A recent study conducted in Japan found that the tumor tissues of 5 of 5 analyzed adult patients with PF/PM lesions expressed a high level of an abnormal c-Fos protein. This protein was a fusion protein formed by a chromosomal translocation between two disparate genes: the c-Fos gene[11] (also termed FOS), a potential cancer-causing oncogene, normally located at chromosome band 24.3 on the long arm (i.e. q arm) of chromosome 14 and the VIM gene,[12] normally located at band 13 on the short arm (i.e. p arm) of chromosome 10. The FOS:VIM fusion gene along with its c-Fos-VIM protein (which possesses uncontrolled c-Fos activity) are associated with the development and/or progression of some other fibroblastic and myofibroblastic tumors as well as malignant sarcomas. The FOS:VIM fusion gene and c-Fos-VIM fusion protein were found primarily in the epithelioid ganglion-like cell cells but mostly absent in the spindle-shaped cells of these lesion. The tumor of the single young person (1 year/old male) analyzed showed no evidence of this fusion gene or fusion protein. While these findings must be confirmed in a larger number of individuals, they do suggest that: 1) the FOS:VIM fusion gene and c-Fos-VIM fusion protein may contribute to the development of PF/PM in adults; 2) this fusion gene and its protein product may not be involved in childhood PF/PM tumors which also differ from adult PF/PM tumors in their histopathology (see the above Pathology section); and 3) the epithelioid ganglion-like cells but not spindle-shaped cells or any other cell types in adult PF/PM tumors may be neoplastic.[6] It is further suggested that spontaneously reversing and self-limiting PF/PM tumors in adults are "transient neoplasms" similar to other theorized transient neoplasms[6] such as nodular fasciitis[13][14] myositis ossificans,[15] aneurysmal bone cyst, and giant cell lesion of small bones.[16] Two other genetic abnormalities have been reported in PF/PM tumors: trisomy 2 (i.e. the presence of an extra chromosome 2) in the tumor cells of two cases[17][18] and a translocation of genetic material between band 23 on the long arm of chromosome 6 and band 32 on the long arm of chromosome 14 in the tumor cells of one case.[19] Neither of these abnormalities have been validated, further characterized, or confirmed in other studies.[6] Finally, 2 of 20 proliferative fasciitis tumors tested positive for the abnormal expression of FOSB protein, a product of the FOSB oncogene.[20][21][22]

Diagnosis

[edit]The diagnosis of PF/PM lesions depends or their presentation and, most importantly, their histopathology showing the presence of epithelioid ganglion-like cell cells. The presence of at least some of these signature cells in a lesion with an appropriate presentation in either a soft tissue or muscle tissue is considered definitive evidence that the lesion is a PF/PM.[10][6] Analyses of tumor tissues for c-FOS may turn out be another useful marker for PF/PM.[6]

Treatment and prognosis

[edit]The primary treatment for PF/PM lesions is watchful waiting, i.e. following the lesions for spontaneous regression or any possible complications that require surgical intervention. Symptomatic therapy such as analgesics, e.g. nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, may be required to treat pain or rare cases of fever.[1] Rare PF/PM lesions may require surgical excision when, for example, they interfere with blood flow[23] or produce a painful, poorly functional hand due to the tumor inducing a trigger finger,[24] Surgical resections in these cases are generally curative.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nishi TM, Yamashita S, Hirakawa YN, Katsuki NE, Tago M, Yamashita SI (September 2019). "Proliferative Fasciitis/Myositis Involving the Facial Muscles Including the Masseter Muscle: A Rare Cause of Trismus". The American Journal of Case Reports. 20: 1411–1417. doi:10.12659/AJCR.917193. PMC 6777384. PMID 31551403.

- ^ a b c d e Porrino J, Al-Dasuqi K, Irshaid L, Wang A, Kani K, Haims A, Maloney E (June 2021). "Update of pediatric soft tissue tumors with review of conventional MRI appearance-part 1: tumor-like lesions, adipocytic tumors, fibroblastic and myofibroblastic tumors, and perivascular tumors". Skeletal Radiology. 51 (3): 477–504. doi:10.1007/s00256-021-03836-2. PMID 34191084. S2CID 235678096.

- ^ a b c d e Brooks JK, Scheper MA, Kramer RE, Papadimitriou JC, Sauk JJ, Nikitakis NG (April 2007). "Intraoral proliferative myositis: case report and literature review". Head & Neck. 29 (4): 416–20. doi:10.1002/hed.20530. PMID 17111425. S2CID 9698761.

- ^ Sbaraglia M, Bellan E, Dei Tos AP (April 2021). "The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: news and perspectives". Pathologica. 113 (2): 70–84. doi:10.32074/1591-951X-213. PMC 8167394. PMID 33179614.

- ^ Wong NL, Di F (December 2009). "Pseudosarcomatous fasciitis and myositis: diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 132 (6): 857–65. doi:10.1309/AJCPLEPS44PJHDPP. PMID 19926576.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Makise N, Mori T, Motoi T, Shibahara J, Ushiku T, Yoshida A (May 2021). "Recurrent FOS rearrangement in proliferative fasciitis/proliferative myositis". Modern Pathology. 34 (5): 942–950. doi:10.1038/s41379-020-00725-2. PMID 33318581. S2CID 228627775.

- ^ Satish S, Shivalingaiah SC, Ravishankar S, Vimalambika MG (October 2012). "Fine needle aspiration cytology of pseudosarcomatous reactive lesions of soft tissues: A report of two cases". Journal of Cytology. 29 (4): 264–6. doi:10.4103/0970-9371.103949. PMC 3543599. PMID 23326034.

- ^ a b c Gan S, Xie D, Dai H, Zhang Z, Di X, Li R, Guo L, Sun Y (2019). "Proliferative myositis and nodular fasciitis: a retrospective study with clinicopathologic and radiologic correlation". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 12 (12): 4319–4328. PMC 6949867. PMID 31933833.

- ^ Meis JM, Enzinger FM (April 1992). "Proliferative fasciitis and myositis of childhood". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 16 (4): 364–72. doi:10.1097/00000478-199204000-00005. PMID 1566969. S2CID 20591490.

- ^ a b c Forcucci JA, Bruner ET, Smith MT (January 2016). "Benign soft tissue lesions that may mimic malignancy". Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology. 33 (1): 50–9. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2015.09.007. PMID 26490572.

- ^ "FOS Fos proto-oncogene, AP-1 transcription factor subunit [Homo sapiens (Human)] - Gene - NCBI".

- ^ "VIM vimentin [Homo sapiens (Human)] - Gene - NCBI".

- ^ Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, Roth CW, Seys AR, Jin L, Ye Y, Lau AW, Wang X, Oliveira AM (October 2011). "Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion". Laboratory Investigation. 91 (10): 1427–33. doi:10.1038/labinvest.2011.118. PMID 21826056.

- ^ Oliveira AM, Chou MM (January 2014). "USP6-induced neoplasms: the biologic spectrum of aneurysmal bone cyst and nodular fasciitis". Human Pathology. 45 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2013.03.005. PMID 23769422.

- ^ Švajdler M, Michal M, Martínek P, Ptáková N, Kinkor Z, Szépe P, Švajdler P, Mezencev R, Michal M (June 2019). "Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of digits and myositis ossificans show consistent COL1A1-USP6 rearrangement: a clinicopathological and genetic study of 27 cases". Human Pathology. 88: 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2019.02.009. PMID 30946936. S2CID 133544364.

- ^ Flucke U, Shepard SJ, Bekers EM, Tirabosco R, van Diest PJ, Creytens D, van Gorp JM (August 2018). "Fibro-osseous pseudotumor of digits - Expanding the spectrum of clonal transient neoplasms harboring USP6 rearrangement" (PDF). Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 35: 53–55. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.05.003. PMID 29787930. S2CID 44139358.

- ^ Bridge JA, Dembinski A, DeBoer J, Travis J, Neff JR (March 1994). "Clonal chromosomal abnormalities in osteofibrous dysplasia. Implications for histopathogenesis and its relationship with adamantinoma". Cancer. 73 (6): 1746–52. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19940315)73:6<1746::aid-cncr2820730632>3.0.co;2-w. PMID 8156503.

- ^ Ohjimi Y, Iwasaki H, Ishiguro M, Isayama T, Kaneko Y (September 1994). "Trisomy 2 found in proliferative myositis cultured cell". Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 76 (2): 157. doi:10.1016/0165-4608(94)90470-7. PMID 7923069.

- ^ McComb EN, Neff JR, Johansson SL, Nelson M, Bridge JA (October 1997). "Chromosomal anomalies in a case of proliferative myositis". Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 98 (2): 142–4. doi:10.1016/s0165-4608(96)00428-1. PMID 9332481.

- ^ "FOSB FosB proto-oncogene, AP-1 transcription factor subunit [Homo sapiens (Human)] - Gene - NCBI".

- ^ "WikiGenes - Collaborative Publishing".

- ^ Hung YP, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL (May 2017). "FOSB is a Useful Diagnostic Marker for Pseudomyogenic Hemangioendothelioma". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 41 (5): 596–606. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000795. PMID 28009608. S2CID 35638467.

- ^ Haloi AK, Seith A, Chumber S, Bandhu S, Panda SK, Mannan SR (January 2004). "Case of the season: proliferative myositis". Seminars in Roentgenology. 39 (1): 4–6. doi:10.1016/j.ro.2003.10.001. PMID 14976833.

- ^ Vlaic J, Fattorini MZ, Dukaric N, Tomas D (September 2020). "Proliferative fasciitis: A rare cause of disturbances in an adolescent hand". Acta Orthopaedica et Traumatologica Turcica. 54 (5): 557–560. doi:10.5152/j.aott.2020.19033. PMC 7646621. PMID 32442126.

- ^ Rosenberg AE (April 2008). "Pseudosarcomas of soft tissue". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 132 (4): 579–86. doi:10.5858/2008-132-579-POST. PMID 18384209.