Transgender rights in Brazil

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ rights |

|---|

|

| Lesbian ∙ Gay ∙ Bisexual ∙ Transgender ∙ Queer |

|

|

Transgender rights in Brazil include the right to change one's legal name and sex without the need of surgery or professional evaluation, and the right to sex reassignment surgery provided by Brazil's public health service, the Sistema Único de Saúde.

Gender recognition

[edit]History

[edit]Before 2009

In 1993, the first Brazilian national meeting was held among transgender individuals.[1] This meeting was known as the National Meeting of Transvestites and Liberated People.[1] By 1995, gay and lesbian national meetings were being attended by transgender activist groups.[1] Then, in 1996, the National Meeting of Transvestites and Liberated People Fighting Against AIDS was held.[1]

Brazil participated in the drafting of the Statement on Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. This document was presented in December 2008.[2] Brazil helped organize the launch of the Yogyakarta Principles in 2007.[2]

Since 2009

[edit]Changing legal gender assignment in Brazil is legal according to the Superior Court of Justice of Brazil, as stated in a decision rendered on 17 October 2009.[3]

Unanimously, the 3rd Class of the Superior Court of Justice approved allowing the option of name and gender change on the birth certificate of a transgender person who has undergone sex reassignment surgery.

The understanding of the ministers was that it made no sense to allow people to have such surgery performed in the free federal health system and not allow them to change their name and gender in the civil registry.[4]

The ministers followed the vote of the rapporteur, Nancy Andrighi, who argued that "if Brazil consents to the possibility of surgery, it should also provide the means for the individual to have a decent life in society". In the opinion of the rapporteur, preventing the record change for a transgender person who has gone through sex reassignment surgery could constitute a new form of social prejudice, and cause more psychological instability.[5] She explained:

"The issue is delicate. At the beginning of compulsory civil registry, distinction between the two sexes was determined according to the genitalia. Today there are other influential factors, and that identification can no longer be limited to the apparent sex. There is a set of social, psychological problems that must be considered. Vetoing this exchange would be putting the person in an untenable position, subject to anxieties, uncertainty, and more conflict."[6]

According to Minister João Otávio de Noronha of the Superior Court of Justice, transgender people should have their social integration ensured with respect to their dignity, autonomy, intimacy and privacy, which must therefore incorporate their civil registry.[7]

Since 2018

[edit]The Supreme Federal Court ruled on 1 March 2018, that a transgender person has the right to change their official name and sex without the need of surgery or professional evaluation, just by self-declaration of their psychosocial identity. On 29 June, the Corregedoria Nacional de Justiça, a body of the National Justice Council published the rules to be followed by registry offices concerning the subject.[8]

In 2020, a study was conducted to understand the quality of life of Brazilian transgender children.[9] 32 participants were involved in the study, and they were either interviewed or placed into focus groups to gather their perspective.[9]

Social name

[edit]The term social name is the designation by which someone identifies and is socially recognized, replacing the name given at birth or civil registry.[10] At the federal level, the main law that guarantees the use of the corporate name is from April 2016. This decree regulated the use of the social name by bodies and entities of the direct, autonomous, and foundational federal public administration. This includes bodies such as the INSS, Receita Federal (CPF), hospitals and universities. Since then, the social name has been recognized in various contexts, including the SUS, banks, and education systems.[11]

Non-binary recognition

[edit]

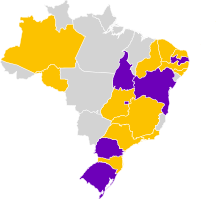

There is no recognition of a third gender option nationwide, but since 2020 non-binary and intersex people have been getting court authorizations to register their sex as "unspecified", "non-identified", "intersex",[12] or "non-binary" in the civil registry.[13][14][15][16] For the purpose of filling out and printing the Identity Card, the gender field must follow the ICAO standardization, with 1 character, M, F or X (for non-binary people). Since January 11, 2024, issuing bodies in the States and the Federal District have been obliged to adopt these Identity Card standards established by the Federal Government. The information in the gender field can be self-determined and self-declared by the person when filling in the data, at the Identification Institutes. In the current context, of the 3,502,816 IDs issued, there are 192 National Identity Cards, that is, 0.01% defined in the gender field as "X".[17][18]

While requesting a new passport, Brazilians are able to select an unspecified sex. According to the Federal Police, the body responsible for issuing Brazilian passports, in response to the requirement for access to registered information, the "not specified" option, in these terms, was implemented in the application form passport application in 2007, with the advent of the "New Passport", popularly known as the "blue cape model". Before that, however, the option already existed, and was declared on printed and typed forms in the old "cover model" notebooks green". Following the international standard, the "unspecified" option is represented in the passport with the letter X, instead of the letters M or F, for male or female, respectively. The gender option contained in the passport must reflect the information expressed in the birth certificate or other official identification document. I.e, whenever the information expressed on the certificate is different from "male" or "female", the alternative will be used. The use of option X, or "not specified", comes from the international standard ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization), which specifies the printing of the "Gender of the holder" by "use of the initial letter commonly used in the country of origin", being "capital letter F for feminine, M for masculine, or X for unspecified". Following ICAO standards, among others, is precisely what confers recognition of a passport by other countries.[19][20]

Since 12 September 2021, by decision of the National Justice Council, notaries must register intersex children with the sex ignored on birth certificates.[21][22][23][24]

The state of Rio de Janeiro, thanks to the work of the State Public Defender's Office, has been allowing non-binary people to register their birth certificates and identity cards with the "non-binary" gender in gender-neutral language.[25][26]

On April 22, 2022, Rio Grande do Sul Justice assured non-binary people to change their first name and sex in their birth record, according to their self-perceived identity, regardless of judicial authorization, allowing include the expression "non-binary" in the sex field upon a request made by the interested party to a notary's office.[27][28]

On May 9, 2022, Bahia Justice publishes provision allowing the inclusion of “non-binary” gender in the Civil Registry.[29][30]

In 2023, Paraíba, Paraná, Tocantins, and Federal District recognized non-binary gender markers.[31][32][33][34] However, in October 2023, the National Justice Council, at the request of the TJES, issued a document precluding "non-binary" as a gender marker. The document quotes Luiz Fux, who claimed that “(…) There is no third gender, nor is this the claim”.[35][36] In November 2023, TJPR revoked non-binary recognition, establishing that the right to administrative replacement of first name and sex in civil registration does not cover the possibility of expanding genders, limited to “male” and “female”.[37] TJRS, in December 2023, also revoked the provision that recognized non-binary rectification in the state of Rio Grande do Sul.[38]

In January 2024, a public civil action by the Federal Court of Paraná determined that the Federal Revenue must include the options "unspecified", "non-binary" and "intersex" in the sex field of the CPF, guaranteeing the right to rectification to those who interest.[39]Transgender healthcare

[edit]Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), the public health system in Brazil, provides processo transexualizador (PrTr or PT-SUS, English: transsexualizing process).[40] This includes psychological counseling, hormone therapy, and sex reassignment surgeries.[41]

Since 2008, the SUS has offered sex reassignment surgeries free of charge, in accordance with a court ruling that recognizes the importance of these procedures for the health and well-being of trans people.[42] In addition, Ordinance No. 2,803 of 2013 redefined and expanded the Transsexualization Process,[43][44] ensuring a more comprehensive and inclusive approach. And it made adjustments in 2023.[45][46]

Gender reassignment surgery

[edit]The first male-to-female gender-affirming surgery in Brazil was Performed by Dr. Roberto Farina in the 1970s. He was prosecuted for his actions but was eventually acquitted of all charges in 1979.[47]

In 2008, Brazil's public health system started providing free sex reassignment surgery in compliance with a court order. Federal prosecutors had argued that gender reassignment surgery was covered under a constitutional clause guaranteeing medical care as a basic right.[48]

The Regional Federal Court agreed, saying in its ruling:

"from the biomedical perspective, transsexuality can be described as a sexual identity disturbance where individuals need to change their sexual designation or face serious consequences in their lives, including intense suffering, mutilation and suicide."

Patients must be at least 18 years old and diagnosed as transgender with no personality disorders, and must undergo psychological evaluation with a multidisciplinary team for at least two years, begins with 16 years old. The national average is of 100 surgeries per year, according to the Ministry of Health of Brazil.[49]

Transgender discrimination

[edit]There were about 200 homicides of transgender individuals in Brazil in 2017, according to the Brazilian National Transgender Association.[50] Additionally, Brazil made up 40% of all murders of transgender individuals since 2008, according to Transgender Europe.[50] More recently, the number of transgender women murdered in Brazil went up 45% in 2020.[51]

São Paulo city council member Erika Hilton, the first transgender woman to be elected to the city council, received death threats and, as a result, had to change her habits for safety reasons.[51]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Corrales, Javier; Pecheny, Mario (2010). The Politics of Sexuality in Latin America. University of Pittsburgh Pre. ISBN 978-0-8229-7371-3.

- ^ a b Nogueira, Maria Beatriz Bonna (2017). "The Promotion of LGBT Rights as International Human Rights Norms: Explaining Brazil's Diplomatic Leadership". Global Governance. 23 (4): 545–563. doi:10.1163/19426720-02304003. ISSN 1075-2846. JSTOR 44861146.

- ^ Transgenders can change their name, as decided by the Supreme Court of Justice (in Portuguese)

- ^ Gender reassignment surgery is free in Brazil (in Portuguese)

- ^ Jurisprudence of the Changing legal gender assignment in Brazil by Superior Court (in Portuguese)

- ^ The Superior Court of Justice allows transsexuals to change name and sex on birth certificate (in Portuguese)

- ^ Legal change of name in Brazil (in Portuguese) Archived 23 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Transexuals can now change their names in documents at registry offices throughout the country (in Portuguese)

- ^ a b Nascimento, Fernanda Karla; Reis, Roberta Alvarenga; Saadeh, Alexandre; Demétrio, Fran; Rodrigues, Ivaneide Leal Ataide; Galera, Sueli Aparecida Frari; Santos, Claudia Benedita dos (6 November 2020). "Brazilian transgender children and adolescents: Attributes associated with quality of life". Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 28: e3351. doi:10.1590/1518-8345.3504.3351. ISSN 1518-8345. PMC 7647416. PMID 33174991.

- ^ "Nome social na educação – o que é e qual sua importância". Saber Viver UFRGS (in Brazilian Portuguese). 22 January 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Bancos facilitam uso de nome social por pessoas trans em cartões de crédito e débito". Folha de S.Paulo (in Brazilian Portuguese). 20 July 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Intersexo: entenda o termo que foi pela primeira vez reconhecido em um registro civil no Brasil". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 10 March 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Em decisão inédita no Brasil, Justiça do Rio autoriza certidão de nascimento com registro de 'sexo não especificado'" [In an unprecedented decision in Brazil, Justice of Rio authorizes birth certificate with 'unspecified sex' registration]. Extra Online (in Brazilian Portuguese). 21 September 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Pessoa agênero obtém na Justiça o direito de ser registrada como 'neutra' na certidão de nascimento" [Agender person obtains in court the right to be registered as 'neutral' on the birth certificate]. O Globo (in Brazilian Portuguese). 13 April 2021. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Serena, Ilanna (23 July 2021). "Pela primeira vez, Justiça piauiense concede registro de pessoa não-binária à jovem" [For the first time, Piauí court grants registration of non-binary gender to young person]. G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ g1 (19 May 2023). "Nova carteira de identidade não terá campo 'sexo' nem distinção entre 'nome' e 'nome social', diz governo".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Presidência da República Federativa do Brasil. "DECRETO Nº 10.977, DE 23 DE FEVEREIRO DE 2022".

- ^ CÂMARA-EXECUTIVA FEDERAL DE IDENTIFICAÇÃO DO CIDADÃO. "RESOLUÇÃO Nº 9, DE 7 DE NOVEMBRO DE 2022" (PDF).

- ^ "Nova solicitação de passaporte - Portal da Polícia Federal" [New passport application]. Federal Police of Brazil. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016.

- ^ "O atual entendimento legal sobre o gênero não binário". Migalhas (in Brazilian Portuguese). 20 September 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Provimento Nº 122 de 13/08/2021". Conselho Nacional de Justiça (CNJ).

- ^ "Provimento do CNJ sobre registro de crianças intersexo com "sexo ignorado" já vale em todo o país". IBDFAM. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Em três anos, região têm 18 registros de crianças com sexo ignorado; nova norma facilita certidão para 'intersexos'". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 29 August 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Decisão do CNJ deixa certidão de nascimento de intersexos menos burocrática". Universo Online (UOL) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Gênero 'não binarie' é incluído em certidões de nascimento no Rio". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 30 January 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Gênero 'não binárie' é incluído na carteira de identidade no RJ". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 5 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Após pedido da DPE/RS, Cartórios passam a aceitar o termo não binário nos registros civis". Defensoria Pública do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (in Brazilian Portuguese). 23 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Justiça autoriza pessoas não binárias a mudar registros de prenome e gênero em cartórios do RS". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 23 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Justiça da BA publica provimento permitindo a inclusão de gênero "não binário" no Registro Civil". Arpen Brasil - Saiba Mais (in Brazilian Portuguese). 11 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "Pessoas não-binárias poderão alterar nome e gênero em registro de nascimento sem autorização judicial na Bahia". Ministério Público do Estado da Bahia (in Brazilian Portuguese). 12 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ "TJPR orienta Registradores Civis a utilizarem o termo "não binário"". Ministério Público do Estado do Paraná (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Paraíba, Jornal da (27 January 2023). "Pessoas não binárias podem alterar nome no registro civil, na Paraíba". jornaldaparaiba.com.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "Pessoas não-binárias podem pedir mudança de nome e gênero diretamente nos cartórios do DF; veja como fazer". G1 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 23 August 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Corregedoria-Geral da Justiça do Estado do Tocantins. "Provimento Nº 3 - CGJUS/2JACGJUS (Art. 780, § 4º)".

- ^ "08/01/2024 – CNJ – Corregedoria Nacional de Justiça publica Decisão que aprimora as regras de averbação de alteração de nome, de gênero ou de ambos de pessoas transgênero – Anoreg-pb" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "Provimento Nº 152 de 26/09/2023". Atos (in Portuguese). 2023. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ "DECISÃO Nº 9746572 - GC SEI! 0134225-12.2022.8.16.6000 I." tjpr.jus.br.

- ^ Anoreg/RS. "Provimento nº 46/2023-CGJ revoga o Provimento nº 16/22 e altera artigos da CNNR – Anoreg RS" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Santos, Rafa (30 January 2024). "União terá de adequar formulários do CPF para incluir diversos gêneros". Consultor Jurídico. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Popadiuk, Gianna Schreiber; Oliveira, Daniel Canavese; Signorelli, Marcos Claudio (May 2017). "A Política Nacional de Saúde Integral de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais e Transgêneros (LGBT) e o acesso ao Processo Transexualizador no Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS): avanços e desafios". Ciência & Saúde Coletiva (in Portuguese). 22: 1509–1520. doi:10.1590/1413-81232017225.32782016. ISSN 1413-8123.

- ^ Petry, Analídia Rodolpho (April–June 2015). "Mulheres transexuais e o Processo Transexualizador: experiências de sujeição, padecimento e prazer na adequação do corpo". Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem (in Portuguese). 36: 70–75. doi:10.1590/1983-1447.2015.02.50158. ISSN 0102-6933.

- ^ Borba, Rodrigo (January–April 2016). "Receita Para Se Tornar Um "Transexual Verdadeiro": Discurso, Interação e (Des)identifição No Processo Transexualizador". Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada (in Portuguese). 55: 33–75. doi:10.1590/010318135029178631. ISSN 2175-764X.

- ^ Rocon, Pablo Cardozo; Sodré, Francis; Rodrigues, Alexsandro (July–September 2016). "Regulamentação da vida no processo transexualizador brasileiro: uma análise sobre a política pública". Revista Katálysis (in Portuguese). 19: 260–269. doi:10.1590/1414-49802016.00200011. ISSN 1982-0259.

- ^ Munin, Pietra Mello (2018). "Processo Transexualizador: discurso, lutas e memórias - Hospital das Clínicas de São Paulo (1997-2013)". bdtd.ibict.br. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "Resolução nº 719 de 17 agosto de 2023" (PDF). Portal Gov.br.

- ^ "Atenção Em Saúde Transespecífica À Crianças e Adolescentes No Contexxto de Ofensiva Antitrans" (PDF).

- ^ Rodrigues Vieira, Tereza (1998). "Mudança de Sexo: Aspectos Médicos, Psicológicos e Jurídicos". Akrópolis - Revista de Ciências Humanas da UNIPAR. 6 (21): 3–8 – via Open Journal Systems.

- ^ Sex-change in Brazil (in Portuguese)

- ^ "Brazil to provide free sex-change operations (in English)". Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013. Brazil to provide free sex-change operations (in English)

- ^ a b Malta, Monica (2 November 2018). "Human rights and political crisis in Brazil: Public health impacts and challenges". Global Public Health. 13 (11): 1577–1584. doi:10.1080/17441692.2018.1429006. ISSN 1744-1692. PMID 29368578. S2CID 40520214.

- ^ a b Nugent, C. (2021). Erika Hilton. Time International (Atlantic Edition), 198(15/16), 91. https://ezproxy.gl.iit.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=159398591&site=ehost-live