Private press

Private press publishing, with respect to books, is an endeavor performed by craft-based expert or aspiring artisans, either amateur or professional, who, among other things, print and build books, typically by hand, with emphasis on design, graphics, layout, fine printing, binding, covers, paper, stitching, and the like.

Description

[edit]The term "private press" is not synonymous with "fine press", "small press", or "university press" – though there are similarities. One similarity shared by all is that they need not meet higher commercial thresholds of commercial presses. Private presses, however, often have no profit motive. A similarity shared with fine and small presses, but not university presses, is that for various reasons – namely quality – production quantity is often limited. University presses are typically more automated. A distinguishing quality of private presses is that they enjoy sole discretion over literary, scientific, artistic, and aesthetic merits. Criteria for other types of presses vary. From an aesthetic perspective, critical acclaim and public appreciation of artisans' works from private presses is somewhat analogous to that of luthiers' works of fine string instruments and bows.

Etymological perspective

[edit]The private press movement, and its renowned body of work – relative to the larger world of book arts in Western civilization – is narrow and recent. From one perspective, collections relating to book arts date back to before the High Middle Ages. As an illustration of scope and influence, a 1980 exhibition at Catholic University of America, "The Monastic Imprint," highlighted the influence of book arts and textual scholarship from 1200 to 1980, displaying hundreds of diplomas, manuscript codices, incunabula, printed volumes, and calligraphic and private press ephemera. The displays focused on five areas: (1) Medieval Monasticism, Spirituality, and Scribal Culture, A.D. 1200–1500; (2) Early Printing and the Monastic Scholarly Tradition, ca. 1450–1600; (3) Early modern Monastic Printing and Scholarly Publishing, A.D. 1650–1800; (4) Modern Survivals: Monastic Scriptoria, Private Presses, and Academic Publishing, 1800–1980.[1][2]

The earliest descriptive references to private presses were by Bernardus A. Mallinckrodt of Mainz, Germany, in De ortu ac progressu artis typographicae dissertatio historica (Cologne, 1639). The earliest in-depth writing about private presses was by Adam Heinrich Lackmann (de) (1694–1754) in Annalium Typographicorum, Selecta Quaedam Capita (Hamburg, 1740).[3]

Private press movement

[edit]By location

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]The term "private press" is often used to refer to a movement in book production which flourished around the turn of the 20th century under the influence of the scholar-artisans William Morris, Sir Emery Walker and their followers. The movement is often considered to have begun with the founding of Morris' Kelmscott Press in 1890, following a lecture on printing given by Walker at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in November 1888. Morris decried that the Industrial Revolution had ruined man's joy in work and that mechanization, to the extent that it has replaced handicraft, had brought ugliness with it. Those involved in the private press movement created books by traditional printing and binding methods, with an emphasis on the book as a work of art and manual skill, as well as a medium for the transmission of information. Morris was greatly influenced by medieval codices and early printed books and the 'Kelmscott style' had a great, and not always positive, influence on later private presses and commercial book-design. The movement was an offshoot of the Arts and Crafts movement, and represented a rejection of the cheap mechanised book-production methods which developed in the Victorian era. The books were made with high-quality materials (handmade paper, traditional inks and, in some cases, specially designed typefaces), and were often bound by hand. Careful consideration was given to format, page design, type, illustration and binding, to produce a unified whole. The movement dwindled during the worldwide depression of the 1930s, as the market for luxury goods evaporated. Since the 1950s, there has been a resurgence of interest, especially among artists, in the experimental use of letterpress printing, paper-making and hand-bookbinding in producing small editions of 'artists' books', and among amateur (and a few professional) enthusiasts for traditional printing methods and for the production 'values' of the private press movement.[4][5][6]

New Zealand

[edit]In New Zealand university private presses have been significant in the private press movement.[7] Private presses are active at three New Zealand universities: Auckland (Holloway Press[8]), Victoria (Wai-te-ata Press[9]) and Otago (Otakou Press[10]).

North America

[edit]A 1982 Newsweek article about the rebirth of the hand press movement asserted that Harry Duncan was "considered the father of the post-World War II private-press movement."[11] Will Ransom has been credited as the father of American private press historiographers.[12]

Selected history

[edit]Quality control

[edit]Beyond aesthetics, private presses, historically, have served other needs. John Hunter (1728–1793), a Scottish surgeon and medical researcher, established a private press in 1786 at his house at 13 Castle Street, Leicester Square, in West End of London, in an attempt to prevent unauthorized publication of cheap and foreign editions of his works. His first book from his private press: A Treatise on the Venereal Disease. One thousand copies of the first edition were printed.[13]

Academics

[edit]Porter Garnett (1871–1951), of Carnegie Mellon University, was an exponent of the anti-industrial values[vague] of the great private presses – namely those of Kelmscott, Doves, and Ashendene. Following Garnett's inspirational proposal to Carnegie Mellon, Garnett designed and inaugurated on April 7, 1923, the institute's Laboratory Press – for the purpose of teaching printing, which he believed was the first private press devoted solely for that purpose. The press closed in 1935.[14]

Selected examples

[edit]United States

[edit]- Abattoir Editions, founded by Harry Alvin Duncan (1916–1997), subsidized by the University of Nebraska Omaha

- Appledore Private Press, set-up in 1867 by William James Linton at Appledore (his house), in Hamden, Connecticut

- Arion Press, founded 1974 by Andrew Hoyem in San Francisco

- Bird & Bull Press, founded 1952 by Henry Martin Morris (born 1925), located in Newtown, Pennsylvania

- Black Rock Press, founded 1965 by Kenneth J. Carpenter at the University of Nevada, Reno

- William Murray Cheney (1907–2002) of Los Angeles[15]

- Gehenna Press, founded 1942 by Leonard Baskin (1922–2000) in New Haven, Connecticut; in the late 1940s, Baskin moved it to Northampton, Massachusetts

- Something Else Press, founded 1963 in New York City by Dick Higgins; the press moved to West Glover, Vermont

- Stratford Press of Cincinnati, Ohio (1920–1965), was the private press of Elmer Frank Gleason (1882–1965)[15]

- Trovillion Press at the Sign of the Silver Horse, set up 1908 by Hal W. Trovillion (né Hal Weeden Trovillion; 1879–1967) in Herrin, Illinois

Canada

[edit]- M. Bernard Loates, A Private Press, founded in 1968

- Locks' Press, founded in 1979 in Brisbane, Australia, by Fred Lock, PhD (né Frederick Peter Lock; born 1948), and wife (an artist), Margaret Lock (née Margaret Helen Capper); in 1987, they moved to Kingston, Ontario[19]

Ireland

[edit]- Dun Emer Press, founded by Elizabeth Yeats in 1903

United Kingdom

[edit]- Daniel Press in Oxford from 1874 to 1903

- Essex House Press, founded in 1897 by Charles Robert Ashbee (1863–1942) in London

- Golden Cockerel Press, founded 1920 in Waltham St Lawrence by Harold Midgley Taylor (1893–1925)

- Gregynog Press, founded 1922 near Newtown, Powys, Wales, by Gwendoline (1882–1951) and Margaret Davies (1884–1963)

- Happy Dragons' Press founded in 1969 in North Essex

- Jericho Press, founded 1985 in Lancaster by "Chip" Coakley, PhD (né James Farwell Coakley)

- Kelmscott Press, set up by William Morris in 1891

- Kynoch Press, a company-owned press that produced artisan-type books in private editions, founded in 1876, closed 1981[20]

- Nonesuch Press, founded in 1922 in London by Sir Francis Meynell (1891–1975), his 2nd wife, Vera Meynell (née Vera Rosalind Wynn Mendel; 1895–1947), and David Garnett (1892–1981)

- Officina Typographica (the namesake of a bygone constellation), established in 1963 by Stanisław Gliwa (pl) (1910–1986), a Polish expatriate living in London[21]

- Gaetano Polidori's Private Press in London c. 1800

- Rampant Lions Press, founded 1924 in Cambridge by Will Carter (né William Nicholas Carter; 1912–2001), who was 12, and continued by his son Sebastian until 2008

- Strawberry Hill Press — the Officina Arbuteana — of Horace Walpole

France

[edit]- Contact Publishing Company, founded 1923 by Robert McAlmon (1895–1956) in Paris

- Harrison of Paris, founded 1930 by Monroe Wheeler (1899–1988) and Barbara Harrison Wescott (1904–1977) in Paris

- Plain Edition Press, founded around 1930 by Alice B. Toklas (1877–1967) and operated by her and Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) in Paris

Asia-Pacific

[edit]Western Asia

[edit]- The Private Press of Ariel Wardi (surname alt spelling, converting Polish phonological use of "W" to English "V" – "Vardi"), established 1989 in Jerusalem; Ariel (born 1929) is the son of Haim Wardi, PhD (ne Rosenfeld; 1901–1975) (he)[22][23][24]

Opponents

[edit]William Addison Dwiggins (1880–1956), a commercial artist, is lauded for high quality work, namely with Alfred Knopf. And, in contrast to many first-rate book designers joining private presses, he refused. Historian Paul Shaw explained, "He had no patience with those who insisted on retaining hand processes in printing and publishing in the belief that they were inherently superior to machine processes." Dwiggins's "principal concern ultimately centered on readers and their reading needs, esthetic as well as financial. [His] goal was to make books that were beautiful, functional, and inexpensive."[25][26]

Gallery

[edit]-

Roycroft printing press

-

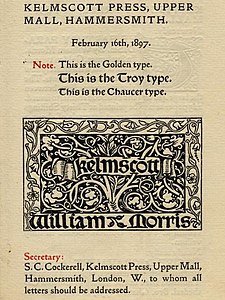

Kelmscott Press font styles

-

Albion press used by the Daniel Press

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Monastic Imprint," co-sponsored by (i) the Rare Books Department of the John K. Mullen Library at Catholic University of America and (ii) the College of Library and Information Services at the University of Maryland (1980)

- ^ "Communications". The Journal of Library History. 15 (4): 521–524. 1980. JSTOR 25541165.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, "Private Presses" (Note 1: "References and Notes"), entry by Roderick Cave, Vol. 24, New York City: Marcel Dekker, Inc., p. 205

- ^ Purves, Drika (1991). "The Gazette". The Yale University Library Gazette. 65 (3/4): 111–115. JSTOR 40859000.

- ^ Horowitz, Sarah (2006). "The Kelmscott Press and William Morris: A Research Guide". Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America. 25 (2): 60–65. doi:10.1086/adx.25.2.27949442. JSTOR 27949442. OCLC 5966431137. S2CID 163588697.

- ^ "Modern Fine Printing," by Colin Franklin, The Guardian, June 25, 1970, p. 9 (accessible via Newspapers.com at www

.newspapers .com /image /259842980) - ^ Vangioni, Peter (2012). Pressed Letters: Fine Printing in New Zealand since 1975, 30 August – 24 September 2012 (PDF). Christchurch, NZ: Christchurch Art Gallery. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ "The Holloway Press". The University of Auckland. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Wai-te-Ata Press". Victoria University of Wellington. Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Otakou Press". University of Otago Library, Special Collections Exhibitions. University of Otago. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Reading the Fine Print," by Ray Anello, Newsweek, August 16, 1982, p. 64

- ^ Schwarz, Philip John (1970). "The Contemporary Private Press". The Journal of Library History. 5 (4): 297–322. JSTOR 25540254. OCLC 5547099053.

- ^ Robb-Smith, A. H. T. (1970). "John Hunter's Private Press". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 25 (3): 262–269. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XXV.3.262. JSTOR 24622127. PMID 4912881.

- ^ Benton, Megan L. (1992). "Orchids from Pittsburgh: An Appraisal of the Laboratory Press, 1922-1935". The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. 62 (1): 28–54. doi:10.1086/602419. JSTOR 4308664. S2CID 144544855.

- ^ a b c "News and Reviews of Private Presses" (monthly column), by James Lamar Weygand (1919–2003), American Book Collector, Vols. 14 and 15

including:

Press of Roy A. Squires

(né Roy Asahel Squires; 1920–1988), Pacific Grove, CaliforniaAshantilly Press

Vol. 14, No. 6, February 1964, p. 13William Greaner Haynes, Jr. (1908–2001), Darien, GeorgiaRed Barn Press

Vol. 14, No. 6, February 1964, p. 13James Marsden, Foxboro, MassachusettsInnominate Press The Hudson Press

Vol. 14, No. 5, January 1964, p. 8William H. Hudson, HoustonThe Stratford Press

Vol. 14, No. 7, March 1964, p. 15Elmer Gleason of CincinnatiWilliam M. Cheney

Vol. 14, No. 9, May 1964, p. 16(né William Murray Cheney; 1907–2002), Los AngelesThe Stone Wall Press

Vol. 15, No. 1, September 1964, p. 7Karl Kimber Merker (1932–2013), Iowa CityBayberry Hill Press

Vol. 15, No. 2, October 1964, p. 7Foster Macy Johnson, Meriden, ConnecticutISSN 0196-5654

Vol. 15, No. 3, November 1964, p. 6 - ^ "Quality Books Slated For Display At UMass," Greenfield Recorder, January 3, 1968, p. 5

- ^ "Two Decades of Hamady and the Perishable Press Limited" (exhibition inventory), University of Missouri–St. Louis, October 3, 1984, through November 4, 1984Subtitled: "Hamady's Perishable Press, A 20th Anniversary Sampling of Hand Crafted Books"OCLC 270104287, 723892183

- ^ Vitello, Paul (May 27, 2013). "Kim Merker, Hand-Press Printer of Poets, Is Dead at 81". The New York Times.

- ^ Locks' Press, Kingston, Ontario, Fred and Margaret Lock (proprietors) (a reissue of a March 2012 catalog, with an additional folded sheet tipped in) (2014), p. 1; OCLC 963257551

- ^ The Kynoch Press: The Anatomy of a Printing House, 1876–1981, by Caroline Archer, PhD (since married to Alexandre Parré and is known as Caroline Archer-Parré), Oak Knoll Press (2000); OCLC 45137620; ISBN 9780712347044

- ^ "Jurzykowski Foundation Awards, 1970". The Polish Review. 16 (2): 105–113. 1971. JSTOR 25776978.

- ^ Avrin, Leila (1997). "Private Presses in Israel". Ariel. 104.

- ^ The Private Press of Ariel Wardi, Jerusalem: A. Wardi (1995); OCLC 1089387256, 32640988

- ^ Karpel, Dalia (October 29, 2016). "The Enigmatic Life of a Hebrew Graphic Design Pioneer". Haaretz.

- ^ "Tradition and Innovation: the design work of William Addison Dwiggins," by Paul Shaw, Design History: An Anthology, Dennis P. Doordan (ed.), MIT Press (1995), pps. 33–35; OCLC 32859908

- ^ Franciosi, Robert (2008). "Designing John Hersey's 'The Wall': W. A. Dwiggins, George Salter, and the Challenges of American Holocaust Memory". Book History. 11: 245–274. doi:10.1353/bh.0.0012. JSTOR 30227420. S2CID 161112866.

Further reading

[edit]- Will Ransom, Private Presses and Their Books. New York City: R. R. Bowker, 1929; OCLC 27326913

- Roderick Cave, The Private Press (2nd ed.). New York City: R. R. Bowker, 1983; OCLC 969849170

- Johanna Drucker, The Century of Artists' Books. New York City: Granary Books, 1995

- Colin Franklin, The Private Presses London: Studio Vista Ltd. (1969);

- Colin Franklin, The Private Presses (2nd ed.). Aldershot: Scolar Press; Brookfield: Gower Publishing Company, 1991; OCLC 551505190, 185502461

- John Carter, ABC for Book Collectors. Oak Knoll Press, 1995; OCLC 270894754

- Charles L. Pickering, HMI, The Private Press Movement, an address by Pickering to the Manchester Society of Book Collectors, Maidstone, Kent: Maidstone College of Art, School of Printing (1967); OCLC 28268389

- Gilbert Turner (1911–1983), The Private Press: Its Achievement and Influence, Birmingham, England: Association of Assistant Librarians, Midland Division (1954); OCLC 940315205

- The Private Press Today, for the 17th King's Lynn Festival: an exhibition, arranged by Juliet Standing, designed to show the scope and quality of work produced during the last few years at various private presses [etc.], illustrations by Rigby Graham, The Riverside Room, July 22–29, 1967, published at The Orchard, Wymondham, Leicestershire by the Brewhouse Press (1967); OCLC 224716056, 57459700, 561420434; OCLC 561420445, 65743870, 640025289

- Bruce Emmerson Bellamy, Private Publishing and Printing Press in England Since 1945, New York City: K. G. Saur Publishing; London: Clive Bingley (1980); OCLC 836260056; ISBN 0-89664-180-5 (U.S.); ISBN 0-85157-297-9 (U.K.)