Glover, Vermont

Glover, Vermont | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Glover Hall | |

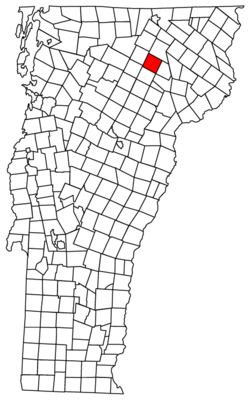

Located in Orleans County, Vermont | |

Location of Vermont with the U.S.A. | |

| Coordinates: 44°41′39″N 72°13′16″W / 44.69417°N 72.22111°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Vermont |

| County | Orleans |

| Chartered | November 20, 1783 |

| Named for | John Glover |

| Communities |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 38.6 sq mi (100.0 km2) |

| • Land | 37.9 sq mi (98.1 km2) |

| • Water | 0.7 sq mi (1.9 km2) |

| Elevation | 945 ft (507 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 1,114 |

| • Density | 30/sq mi (11.4/km2) |

| • Households | 446 |

| • Families | 282 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 05839 |

| Area code | 802 |

| FIPS code | 50-28075[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1462103[2] |

Glover is a town in Orleans County, Vermont, in the United States. As of the 2020 census,[3] the town's population was 1,114. It contains two unincorporated villages, Glover and West Glover.

The town is named for Brigadier General John Glover,[4] who served in the American Revolutionary War. He was the prime proprietor of the town.

Glover is home to three museums: the Bread & Puppet Museum, the Glover Historical Society museum, and The Museum of Everyday Life.[5]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 38.6 square miles (100.0 km2), of which 37.9 square miles (98.1 km2) is land and 0.7 square mile (1.9 km2) (1.92%) is water.

The surface of the town is uneven, with hills and valleys. The highest elevation is Black Hills, at 2,258 feet (688 m), in the south part of town.[6] The town drains northward via the northern branches of the Barton River, and southward via branches of the Passumpsic, Lamoille, and Black Rivers, which have their sources here. Four ponds of considerable size also are found here, Parker Pond, in the north, Clark's pond, in the central, and Sweeney pond in the west, as well as Shadow Lake.[7] Shadow Lake was first called Chambers Pond, then Stone Pond about 1822. In 1922 it was given its current name. The Abenaki had called it Pekdabowk, or Smoke Pond.[8]

History

[edit]In 1802, the town decided to construct one school at the Parker settlement. Operating expenses were limited to $20 for that year.[8]

In the most cataclysmic natural catastrophe affecting Orleans County in post-Columbian times, the banks of Glover's Long Pond gave way on June 6, 1810, and flooded the Barton River valley. The hero of the day was laborer Spencer Chamberlain who ran ahead of the flood to warn people at the mill. The wayward pond was forever after known as "Runaway Pond".

By 1851, there were 450 grammar school students. In 2017, the number of students at that level had dropped to about 100.[8]

From about the 1820s to the 1930s, there was a settlement, Slab City, near the outlet from Shadow Lake, whose economy was dependent on the logging, and three sawmills in the area. The settlement also contained a lime kiln, butter tub factory, a cider mill, a one-room schoolhouse, a post office, a church, and other allied businesses.[9] In 1836, a suit against the height of the water retained in a dam to power the sawmills was successful. The suit was motivated in large part by the Runaway Pond catastrophe. The end of the dam power marked the beginning of the end for Slab City.[8]

The unincorporated village of West Glover had a municipal septic system which failed in 2008.[10] This was replaced in 2012. It connected to the main sewage line in Glover village, which in turns was connected to the wastewater treatment facility in adjacent Barton. This was funded by USDA Rural Development Agency.[11]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 36 | — | |

| 1810 | 387 | 975.0% | |

| 1820 | 549 | 41.9% | |

| 1830 | 902 | 64.3% | |

| 1840 | 1,119 | 24.1% | |

| 1850 | 1,137 | 1.6% | |

| 1860 | 1,244 | 9.4% | |

| 1870 | 1,178 | −5.3% | |

| 1880 | 1,055 | −10.4% | |

| 1890 | 970 | −8.1% | |

| 1900 | 891 | −8.1% | |

| 1910 | 932 | 4.6% | |

| 1920 | 826 | −11.4% | |

| 1930 | 860 | 4.1% | |

| 1940 | 788 | −8.4% | |

| 1950 | 727 | −7.7% | |

| 1960 | 683 | −6.1% | |

| 1970 | 649 | −5.0% | |

| 1980 | 843 | 29.9% | |

| 1990 | 820 | −2.7% | |

| 2000 | 966 | 17.8% | |

| 2010 | 1,122 | 16.1% | |

| 2020 | 1,114 | −0.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

As of the census[1] of 2000, there were 966 people, 384 households, and 269 families residing in the town. The population density was 25.5 inhabitants per square mile (9.8/km2). There were 677 housing units at an average density of 17.9 per square mile (6.9/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 96.38% White, 0.21% African American, 0.93% Native American, 0.21% Asian, 0.31% from other races, and 1.97% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.62% of the population.

There were 384 households, out of which 29.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.9% were married couples living together, 8.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.9% were non-families. 23.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 2.83.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 22.0% under the age of 18, 6.1% from 18 to 24, 23.2% from 25 to 44, 34.1% from 45 to 64, and 14.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 44 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.6 males.

Government

[edit]Town

[edit]- Selectman – Leanne Harple

- Selectman – David Simmons

- Selectman – Phil Young

- Clerk/Treasurer – Cindy Epinette

- Assistant – Theresa Perron

- Library Trustee – Ned Andrews (2013)

- 2010–2011 Budget – 736,525.22

School District

[edit]- Director – Jason Kennedy

- Budget – $1.7 million plus town's assessment for Lake Region Union High School (Orleans Central Supervisory Union)

In 2009 and 2010, the Glover Community School stood highest in the county for averaged proficiency in reading and mathematics on the standardized NE-CAP test.[13][14]

Economy

[edit]Personal Income

[edit]The median income for a household in the town was $46,167. Males had a median income of $25,977 versus $21,172 for females. The per capita income for the town was $15,112. About 10.8% of families and 11.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 15.2% of those under age 18 and 14.9% of those age 65 or over.

The town is second in the county for the highest percentage of second home ownership.[15][16]

Transportation

[edit]Major Routes

[edit]Town maintained roads

[edit]The town has 40 miles (64 km) of dirt roads. These lose an estimated 11,720 cubic yards (8,960 m3) of gravel annually which must be replaced.[17]

Notable people

[edit]- Stephen Bliss, Presbyterian minister and member of the Illinois Senate.[18]

- Emory A. Hebard, Member of the Vermont House of Representatives (1961–1969, 1971–1977) and Vermont State Treasurer (1977–1989)[19]

- Charles Clark Jamieson, U.S. Army brigadier general[20]

- Peter Schumann, founder and director of the Bread & Puppet Theater[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Glover town, Orleans County, Vermont". Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 139.

- ^ "Museum of Every Day Life". Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Orleans County Vermont Summits

- ^ Gazetteer of Lamoille and Orleans Counties, VT.; 1883-1884, Compiled and Published by Hamilton Child; May 1887

- ^ a b c d Starr, Tena (February 1, 2017). "The fascinating story of a lost way of life". the chronicle. Barton, Vermont. pp. 1B, 16B.

- ^ Ashe, Connie (January 9, 2013). "Info about Glover's "Slab City" sought". the chronicle. Barton, Vermont. pp. 16B.

- ^ Braithwaite, Chris (March 5, 2008). Quilts soften mood at crowded Town Meeting. the Chronicle.

- ^ "Wastewater treatment facility is upgraded". the chronicle. Barton, Vermont. February 27, 2013. p. 23.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Braithwaite, Chris (February 3, 2010). "NECAP results show four standouts". Barton, Vermont: the Chronicle. p. 2.

- ^ Starr, Tena (February 15, 2011). "Student test scores released by state". Barton, Vermont: the Chronicle. p. 14.

- ^ The first is Westmore

- ^ Starr, Tena (July 7, 2010). "Glover to study summer people's spending habits". Barton, Vermont: the Chronicle. pp. 10A.

- ^ Creaser, Richard (May 2, 2007). Rough roads are the subject of special meeting. the Chronicle.

- ^ Norton, Augustus Theodore (1879). History of the Presbyterian Church in the State of Illinois. Vol. I. St. Louis, MO: W. S. Bryan. pp. 77–79. ISBN 9780524021330 – via Google Books.

- ^ Samuel B. Hand, Anthony Marro, Stephen C. Terry, Philip Hoff: How Red Turned Blue in the Green Mountain State, 2011

- ^ Davis, Henry Blaine Jr. (1998). Generals in Khaki. Raleigh, NC: Pentland Press, Inc. p. 199. ISBN 1571970886.

- ^ Pollak, Sally (July 10, 2019). "At Bread and Puppet, a 'Memorial Village' Honors Departed Friends and Family". Vermont Seven Days. Burlington, VT.