Monaco

Principality of Monaco | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Deo Juvante" (Latin) (English: "With God's Help") | |

| Anthem: "Hymne Monégasque" (English: "Hymn of Monaco") | |

Location of Monaco (green) in Europe (dark grey) | |

| Capital | Monaco (city-state) 43°43′52″N 07°25′12″E / 43.73111°N 7.42000°E |

| Largest quarter | Monte Carlo |

| Official languages | French[1] |

| Common languages | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Albert II |

| Didier Guillaume | |

| Legislature | National Council |

| Independence | |

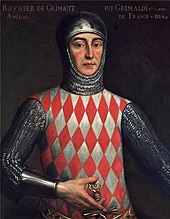

• House of Grimaldi (under the sovereignty of the Republic of Genoa) | 8 January 1297 |

• from the French Empire | 17 May 1814 |

• from occupation of the Sixth Coalition | 17 June 1814 |

| 2 February 1861 | |

| 5 January 1911 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.08 km2 (0.80 sq mi) (194th) |

• Water (%) | negligible[5] |

| Population | |

• 2023 census | |

• Density | 18,446/km2 (47,774.9/sq mi) (1st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $7.672 billion[7] (165th) |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022[b] estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Drives on | right[10] |

| Calling code | +377 |

| ISO 3166 code | MC |

| Internet TLD | .mc |

| |

Monaco,[a] officially the Principality of Monaco,[b] is a sovereign city-state and microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Italian region of Liguria, in Western Europe, on the Mediterranean Sea. It is a semi-enclave bordered by France to the north, east and west. The principality is home to 38,682 residents,[11] of whom 9,486 are Monégasque nationals;[12] it is recognised as one of the wealthiest and most expensive places in the world.[13][14] The official language is French; Monégasque, English and Italian are spoken and understood by many residents.[c]

With an area of 2.08 km2 (0.80 sq mi), Monaco is the second-smallest sovereign state in the world, after Vatican City. Its population of 38,367 in 2023 makes it the most densely populated sovereign state. Monaco has the world's shortest coastline: 3.83 km (2.38 mi).[15] The principality is about 15 km (9.3 mi) from the border with Italy[16] and consists of nine administrative wards, the largest of which is Monte Carlo.

The principality is governed under a form of constitutional monarchy, with Prince Albert II as head of state, who wields political power despite his constitutional status. The prime minister, who is the head of government, can be either a Monégasque or French citizen; the monarch consults with the Government of France before an appointment. Key members of the judiciary are detached French magistrates.[17] The House of Grimaldi has ruled Monaco, with brief interruptions, since 1297.[18] The state's sovereignty was officially recognised by the Franco-Monégasque Treaty of 1861, with Monaco becoming a full United Nations voting member in 1993. Despite Monaco's independence and separate foreign policy, its defence is the responsibility of France, besides maintenance of two small military units.

Monaco's economic development was spurred in the late 19th century with the opening of the state's first casino, the Monte Carlo Casino, and a rail connection to Paris.[19] Monaco's mild climate, scenery, and gambling facilities have contributed to its status as a tourist destination and recreation centre for the rich. Monaco has become a major banking centre and sought to diversify into the services sector and small, high-value-added, non-polluting industries. Monaco is a tax haven; it has no personal income tax (except for French citizens) and low business taxes. Over 30% of residents are millionaires,[20] with real estate prices reaching €100,000 ($116,374) per square metre in 2018. Monaco is a global hub of money laundering, and in June 2024 the Financial Action Task Force placed Monaco under increased monitoring to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.[21][22]

Monaco is not part of the European Union (EU), but participates in certain EU policies, including customs and border controls. Through its relationship with France, Monaco uses the euro as its sole currency. Monaco joined the Council of Europe in 2004 and is a member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF). It hosts the annual motor race, the Monaco Grand Prix, one of the original Grands Prix of Formula One. The local motorsports association gives its name to the Monte Carlo Rally, hosted in January in the French Alps. The principality has a club football team, AS Monaco, which competes in French Ligue 1 and been French champions on multiple occasions, and a basketball team, which plays in the EuroLeague. A centre of research into marine conservation, Monaco is home to one of the world's first protected marine habitats,[23] an Oceanographic Museum, and the International Atomic Energy Agency Marine Environment Laboratories, the only marine laboratory in the UN structure.[24][25]

History

Monaco's name comes from the nearby 6th-century BC Phocaean Greek colony. Referred to by the Ligurians as Monoikos, from the Greek "μόνοικος", "single house", from "μόνος" (monos) "alone, single"[26] + "οἶκος" (oikos) "house".[27] According to an ancient myth, Hercules passed through the Monaco area and turned away the previous gods.[28] As a result, a temple was constructed there. Because this "House" of Hercules was the only temple in the area, the city was called Monoikos.[29][30] It ended up in the hands of the Holy Roman Empire, which gave it to the Genoese.[clarification needed]

An ousted branch of a Genoese family, the Grimaldi, contested it for a hundred years before gaining control. Though the Republic of Genoa would last until the 19th century, they allowed the Grimaldi family to keep Monaco, and, likewise, both France and Spain left it alone for hundreds of years. France did not annex it until the French Revolution, but after the defeat of Napoleon it was put under the care of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

In the 19th century, when Sardinia became a part of Italy, the region came under French influence but France allowed it to remain independent. Like France, Monaco was overrun by the Axis powers during the Second World War and for a short time was administered by Italy, then Nazi Germany, before being liberated. Although the occupation lasted for just a short time, it resulted in the deportation of the Jewish population and execution of several French Resistance members from Monaco. Since then Monaco has been independent. It has taken some steps towards integration with the European Union.

Arrival of the Grimaldi family

Following a grant of land from Emperor Henry VI in 1191, Monaco was refounded in 1215 as a colony of Genoa.[31][32] Monaco was first ruled by a member of the House of Grimaldi in 1297, when Francesco Grimaldi, known as "Malizia" (translated from Italian either as "The Malicious One" or "The Cunning One"), and his men captured the fortress protecting the Rock of Monaco while dressed as Franciscan friars – a monaco in Italian – although this is a coincidence as the area was already known by this name.[33]

Francesco was evicted a few years later by the Genoese forces, and the struggle over "the Rock" continued for another century.[34] The Grimaldi family was Genoese and the struggle was something of a family feud. The Genoese engaged in other conflicts, and in the late 1300s Genoa lost Monaco after fighting the Crown of Aragon over Corsica.[35] Aragon eventually became part of a united Spain, and other parts of the land grant came to be integrated piecemeal into other states. Between 1346 and 1355, Monaco annexed the towns of Menton and Roquebrune, increasing its territory by almost ten times.[35]

1400–1800

In 1419, the Grimaldi family purchased Monaco from the Crown of Aragon and became the official and undisputed rulers of "the Rock of Monaco". In 1612, Honoré II began to style himself "Prince" of Monaco.[36] In the 1630s, he sought French protection against the Spanish forces and, in 1642, was received at the court of Louis XIII as a "duc et pair étranger".[37]

The princes of Monaco became vassals of the French kings while at the same time remaining sovereign princes. Though successive princes and their families spent most of their lives in Paris, and intermarried with French and Italian nobilities, the House of Grimaldi is Italian. The principality continued its existence as a protectorate of France until the French Revolution.[38]

19th century

In 1793, Revolutionary forces captured Monaco and until 1814 it was occupied by the French (in this period much of Europe had been overrun by the French armies under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte).[37][39] The principality was reestablished in 1814 under the Grimaldis. It was designated a protectorate of the Kingdom of Sardinia by the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[39] Monaco remained in this position until 1860 when, by the Treaty of Turin, the Sardinian forces pulled out of the principality; the surrounding County of Nice (as well as Savoy) was ceded to France.[40] Monaco became a French protectorate once again. Italian was the official language in Monaco until 1860, when it was replaced by French.[41]

Before this time there was unrest in Menton and Roquebrune, where the townspeople had become weary of heavy taxation by the Grimaldi family. They declared their independence as the Free Cities of Menton and Roquebrune, hoping for annexation by Sardinia. France protested. The unrest continued until Charles III of Monaco gave up his claim to the two mainland towns (some 95% of the principality at the time) that had been ruled by the Grimaldi family for over 500 years.[42]

These were ceded to France in return for 4,100,000 francs.[43] The transfer and Monaco's sovereignty were recognised by the Franco-Monégasque Treaty of 1861. In 1869, the principality stopped collecting income tax from its residents — an indulgence the Grimaldi family could afford to entertain thanks solely to the extraordinary success of the casino.[44] This made Monaco a playground for the rich and a favoured place for them to live.[45]

20th century

Until the Monégasque Revolution of 1910 forced the adoption of the 1911 Constitution of Monaco, the princes of Monaco were absolute rulers.[46] The new constitution slightly reduced the autocratic rule of the Grimaldi family and Prince Albert I suspended it during the First World War.

In July 1918, a new Franco-Monégasque Treaty was signed, providing for limited French protection over Monaco. The treaty, endorsed in 1919 by the Treaty of Versailles, established that Monégasque international policy would be aligned with French political, military and economic interests. It also resolved the Monaco succession crisis.

In 1943, the Italian Army invaded and occupied Monaco, forming a fascist administration.[47] In September 1943, after Mussolini's fall from power, the German Wehrmacht occupied Italy and Monaco, and the Nazi deportation of the Jewish population began. René Blum, the prominent French Jew who founded the Ballet de l'Opéra in Monte Carlo, was arrested in his Paris home and held in the Drancy deportation camp outside the French capital before being transported to Auschwitz, where he was later murdered.[48] Blum's colleague Raoul Gunsbourg, the director of the Opéra de Monte-Carlo, helped by the French Resistance, escaped arrest and fled to Switzerland.[49] In August 1944, the Germans executed René Borghini, Joseph-Henri Lajoux and Esther Poggio, who were Resistance leaders.

Rainier III, succeeded to the throne on the death of his grandfather, Prince Louis II, in 1949, and ruled until 2005. On 19 April 1956, Prince Rainier married the American actress Grace Kelly, an event that was widely televised and covered in the popular press, focusing the world's attention on the tiny principality.[50]

A 1962 amendment to the constitution abolished capital punishment, provided for women's suffrage and established a Supreme Court of Monaco to guarantee fundamental liberties. In 1963, a crisis developed when Charles de Gaulle blockaded Monaco, angered by its status as a tax haven for wealthy French citizens.[51]

In 1993, the Principality of Monaco became a member of the United Nations, with full voting rights.[40][52]

21st century

In 2002, a new treaty between France and Monaco specified that, should there be no heirs to carry on the Grimaldi dynasty, the principality would still remain an independent nation rather than revert to France. Monaco's military defense is still the responsibility of France.[53][54]

On 31 March 2005, Rainier III, who was too ill to exercise his duties, relinquished them to his only son and heir, Albert.[55] He died six days later, after a reign of 56 years, with his son succeeding him as Albert II, Sovereign Prince of Monaco. Following a period of official mourning, Prince Albert II formally assumed the princely crown on 12 July 2005,[56] in a celebration that began with a solemn Mass at Saint Nicholas Cathedral, where his father had been buried three months earlier. His accession to the Monégasque throne was a two-step event with a further ceremony, drawing heads of state for an elaborate reception, held on 18 November 2005, at the historic Prince's Palace in Monaco-Ville.[57] On 27 August 2015, Albert II apologised for Monaco's role during World War II in facilitating the deportation of a total of 90 Jews and resistance fighters, of whom only nine survived. "We committed the irreparable in handing over to the neighbouring authorities women, men and a child who had taken refuge with us to escape the persecutions they had suffered in France," Albert said at a ceremony in which a monument to the victims was unveiled at the Monaco cemetery. "In distress, they came specifically to take shelter with us, thinking they would find neutrality."[58]

In 2015, Monaco unanimously approved a modest land reclamation expansion intended primarily to accommodate desperately needed housing and a small green/park area.[59] Monaco had previously considered an expansion in 2008, but had called it off.[59] The plan is for about six hectares (15 acres) of apartment buildings, parks, shops and offices to a land value of about 1 billion euros.[60] The development will be adjacent to the Larvotto district and also will include a small marina.[60][61] There were four main proposals, and the final mix of use will be finalised as the development progresses.[62] The name for the new district is Anse du Portier.[61]

On 29 February 2020, Monaco announced its first case of COVID-19, a man who was admitted to the Princess Grace Hospital Centre then transferred to Nice University Hospital in France.[63][64]

On 3 September 2020, the first Monégasque satellite, OSM-1 CICERO, was launched into space from French Guiana aboard a Vega rocket.[65] The satellite was built in Monaco by Orbital Solutions Monaco.

In July 2024, Monaco hosted the start line for final 33 km stage of the 111th Tour de France bicycle race for the first time in 15 years.[66]

Government

Politics

Monaco has been governed under a constitutional monarchy since 1911, with the Sovereign Prince of Monaco as head of state.[67] The executive branch consists of a Prime Minister as the head of government, who presides over the other five members of the Council of Government.[68] Until 2002, the Prime Minister was a French citizen appointed by the prince from among candidates proposed by the Government of France; since a constitutional amendment in 2002, the Prime Minister can be French or Monégasque.[31] On 2 September 2024, Prince Albert II appointed a French citizen, Didier Guillaume, to the office.

Under the 1962 Constitution of Monaco, the prince shares his veto power with the unicameral National Council.[69] The 24 members of the National Council are elected for five-year terms; 16 are chosen through a majority electoral system and 8 by proportional representation.[70] All legislation requires the approval of the National Council. Following the 2023 Monegasque general election, all 24 seats are held by the pro-monarchist Monegasque National Union.[71]

The principality's city affairs are managed by the Municipality of Monaco. The municipality is directed by the Communal Council,[72] which consists of 14 elected members and is presided over by a mayor.[73] Georges Marsan has been mayor since 2003. Unlike the National Council, communal councillors are elected for four-year terms[74] and are strictly non-partisan; oppositions inside the council frequently form.[72][75]

Members of the judiciary of Monaco are appointed by the Sovereign Prince. Key positions within the judiciary are held by French magistrates, proposed by the Government of France. Monaco currently has three examining magistrates.[76]

Security

The wider defence of the nation is provided by France. Monaco has no navy or air force, but on both a per-capita and per-area basis, Monaco has one of the largest police forces (515 police officers for about 38,000 people) and police presences in the world.[77] Its police includes a special unit which operates patrol and surveillance boats jointly with the military. Police forces in Monaco are commanded by a French officer.[78]

There is also a small military force. This consists of a bodyguard unit for the prince and his palace in Monaco-Ville called the Compagnie des Carabiniers du Prince (Prince's Company of Carabiniers);[79] together with the militarised, armed fire and civil defence corps (Sapeurs-Pompiers) it forms Monaco's total forces.[80] The Compagnie des Carabiniers du Prince was created by Prince Honoré IV in 1817 for the protection of the principality and the princely family. The company numbers exactly 116 officers and men; while the non-commissioned officers and soldiers are local, the officers have generally served in the French Army. In addition to their guard duties as described, the carabiniers patrol the principality's beaches and coastal waters.[81]

Geography

Monaco is a sovereign city-state, with five quarters and ten wards,[82] located on the French Riviera in Western Europe. It is bordered by France's Alpes-Maritimes department on three sides, with one side bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Its centre is about 16 km (9.9 mi) from Italy and only 13 km (8.1 mi) northeast of Nice.[52]

It has an area of 2.1 km2 (0.81 sq mi), or 208 ha (510 acres), and a population of 38,400,[83] making Monaco the second-smallest and the most densely populated country in the world.[52] The country has a land border of only 5.47 km (3.40 mi),[83] a coastline of 3.83 km (2.38 mi), a maritime claim that extends 22.2 km (13.8 mi), and a width that varies between 1,700 and 349 m (5,577 and 1,145 ft).[84][85]

Jurassic-era limestone is a prominent bedrock which is locally karstified. It hosts the Grotte de l'Observatoire, which has been open to the public since 1946.[86]

The highest point in the country is at the access to the Patio Palace residential building on the Chemin des Révoires (ward Les Révoires) from the D6007 (Moyenne Corniche street) at 164.4 m (539 ft) above sea level.[87] The lowest point in the country is the Mediterranean Sea.[88]

Saint-Jean brook is the longest flowing body of water, around 0.19 km (190 m; 0.12 mi; 620 ft) in length, and Fontvieille is the largest lake, approximately 0.5 ha (1.2 acres) in area.[89] Monaco's most populated quartier is Monte Carlo, and the most populated ward is Larvotto/Bas Moulins.[90]

After the expansion of Port Hercules,[91] Monaco's total area grew to 2.08 km2 (0.80 sq mi) or 208 ha (510 acres);[90] subsequently, new plans were approved to extend the district of Fontvieille by 0.08 km2 (0.031 sq mi) or 8 ha (20 acres), with land reclaimed from the Mediterranean Sea. Land reclamation projects include extending the district of Fontvieille.[92][93][94][91][95] There are two ports in Monaco, Port Hercules and Port Fontvieille.[96] There is a neighbouring French port called Cap d'Ail that is near Monaco.[96] Monaco's only natural resource is fishing;[97] with almost the entire country being an urban area, Monaco lacks any sort of commercial agriculture industry. A small residential expansion formerly called Le Portier was nearing completion in 2023, and additionally a new esplanade was added at Larvatto beach which also had some maintenance.[98]

Administrative divisions

Monaco is the second-smallest country by area in the world; only Vatican City is smaller.[99] Monaco is the most densely populated country in the world.[100] The state consists of only one municipality (commune), the Municipality of Monaco. There is no geographical distinction between the State and City of Monaco, although responsibilities of the government (state-level) and of the municipality (city-level) are different.[101] According to the constitution of 1911, the principality was subdivided into three municipalities:[102]

- Monaco-Ville, the old city and seat of government of the principality on a rocky promontory extending into the Mediterranean, known as the Rock of Monaco, or simply "The Rock";

- Monte Carlo, the principal residential and resort area with the Monte Carlo Casino in the east and northeast;

- La Condamine, the southwestern section including the port area, Port Hercules.

The municipalities were merged into one in 1917,[103][how?] and they were accorded the status of Wards or Quartiers thereafter.

- Fontvieille was added as a fourth ward, a newly constructed area claimed from the sea in the 1970s;

- Moneghetti became the fifth ward, created from part of La Condamine;

- Larvotto became the sixth ward, created from part of Monte Carlo;

- La Rousse/Saint Roman (including Le Ténao) became the seventh ward, also created from part of Monte Carlo.

Subsequently, three additional wards were created, but then again were dissolved in 2013:

- Saint Michel, created from part of Monte Carlo;

- La Colle, created from part of La Condamine;

- Les Révoires, also created from part of La Condamine.

Most of Saint Michel became part of Monte Carlo again in 2013. La Colle and Les Révoires were merged the same year as part of a redistricting process, where they became part of the larger Jardin Exotique ward. An additional ward was planned by new land reclamation to be settled beginning in 2014[104] but Prince Albert II announced in his 2009 New Year Speech that he had ended plans due to the economic climate at the time.[105] Prince Albert II in mid-2010 firmly restarted the programme.[106][107] In 2015, a new development called Anse du Portier was announced.[61]

Traditional quarters and modern geographic areas

The four traditional quartiers of Monaco are Monaco-Ville, La Condamine, Monte Carlo and Fontvieille.[108] The suburb of Moneghetti, the high-level part of La Condamine, is generally seen today as an effective fifth Quartier of Monaco, having a very distinct atmosphere and topography when compared with low-level La Condamine.[109]

Wards

For town planning purposes, a sovereign ordinance in 1966 divided the principality into reserved sectors, "whose current character must be preserved", and wards. The number and boundaries of these sectors and wards have been modified several times. The latest division dates from 2013 and created two reserved sectors and seven wards. A new 6-hectare district, Le Portier, is currently being built on the sea.

| Wards | Area | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in m2 | in % | |||||

| Reserved Sectors | ||||||

| Ravin de Sainte-Dévote | Reserved Sectors | 23,485 | 1.2 % | |||

| Wards | ||||||

| Monaco-Ville | Quartier ordonnancé | 196,491 | 9.7 % | |||

| La Condamine | Quartier ordonnancé | 295,843 | 14.6 % | |||

| Fontvieille | Quartier ordonnancé | 329,516 | 16.3 % | |||

| Larvotto | Quartier ordonnancé | 217,932 | 10.8 % | |||

| Jardin Exotique | Quartier ordonnancé | 234,865 | 11.6 % | |||

| Les Moneghetti | Quartier ordonnancé | 115,196 | 5.7 % | |||

| Monte-Carlo | Quartier ordonnancé | 436,760 | 21.5 % | |||

| La Rousse | Quartier ordonnancé | 176,888 | 8.7 % | |||

| Total | 2,026,976 | 100 % | ||||

Note: for statistical purposes, the Wards of Monaco are further subdivided into 178 city blocks (îlots), which are comparable to the census blocks in the United States.[90]

Architecture

Monaco exhibits a wide range of architecture, but the principality's signature style, particularly in Monte Carlo, is that of the Belle Époque. It finds its most florid expression in the 1878–9 Casino and the Salle Garnier created by Charles Garnier and Jules Dutrou. Decorative elements include turrets, balconies, pinnacles, multi-coloured ceramics, and caryatids. These were blended to create a picturesque fantasy of pleasure and luxury, and an alluring expression of how Monaco sought and still seeks, to portray itself.[112] This capriccio of French, Italian, and Spanish elements were incorporated into hacienda villas and apartments. Following major development in the 1970s, Prince Rainier III banned high-rise development in the principality. His successor, Prince Albert II, overturned this Sovereign Order.[113] In recent years[when?] the accelerating demolition of Monaco's architectural heritage, including its single-family villas, has created dismay.[114] The principality has no heritage protection legislation.[115]

Climate

Monaco has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa), with strong maritime influences, with some resemblances to the humid subtropical climate (Cfa). As a result, it has balmy warm, dry summers and mild, rainy winters. The winters are very mild considering the city's latitude, being as mild as locations located much further south in the Mediterranean Basin.[116] Cool and rainy interludes can interrupt the dry summer season, the average length of which is also shorter. Summer afternoons are infrequently hot (indeed, temperatures greater than 30 °C or 86 °F are rare) as the atmosphere is temperate because of constant sea breezes. On the other hand, the nights are very mild, due to the fairly high temperature of the sea in summer. Generally, temperatures do not drop below 20 °C (68 °F) in this season. In the winter, frosts and snowfalls are extremely rare and generally occur once or twice every ten years.[117][118] On 27 February 2018, both Monaco and Monte Carlo experienced snowfall.[119]

| Climate data for Monaco (1981–2010 averages, extremes 1966–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

30.3 (86.5) |

32.5 (90.5) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.5 (94.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

29.0 (84.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

34.5 (94.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.9 (80.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.2 (52.2) |

8.5 (47.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.5 (50.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 67.7 (2.67) |

48.4 (1.91) |

41.2 (1.62) |

71.3 (2.81) |

49.0 (1.93) |

32.6 (1.28) |

13.7 (0.54) |

26.5 (1.04) |

72.5 (2.85) |

128.7 (5.07) |

103.2 (4.06) |

88.8 (3.50) |

743.6 (29.28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.0 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 62.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 149.8 | 158.9 | 185.5 | 210.0 | 248.1 | 281.1 | 329.3 | 296.7 | 224.7 | 199.0 | 155.2 | 136.5 | 2,574.7 |

| Source 1: Météo-France[120] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Monaco website (sun only)[121] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Monaco | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.2) |

13.0 (55.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

14.6 (58.4) |

18.0 (64.3) |

21.8 (71.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.6 (74.4) |

22.2 (71.9) |

19.6 (67.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

14.9 (58.9) |

17.9 (64.3) |

| Source: Weather Atlas[122] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Monaco has the world's highest GDP nominal per capita at US$185,742, GDP PPP per capita at $132,571 and GNI per capita at $183,150.[123][124][125] It also has an unemployment rate of 2%,[126] with over 48,000 workers who commute from France and Italy each day.[90] According to the CIA World Factbook, Monaco has the world's lowest poverty rate[127] and the highest number of millionaires and billionaires per capita in the world.[128] For the fourth year in a row, Monaco in 2012 had the world's most expensive real estate market, at $58,300 per square metre.[129][130][131] Although the average price went down in 2020, to an average price of $53,378 per square metre, Monaco remains one of the most expensive places in the world to buy property.[132] The world's most expensive apartment is located in Monaco, a penthouse at the Odeon Tower valued at $335 million according to Forbes in 2016.[133]

One of Monaco's main sources of income is tourism. Each year many foreigners are attracted to its casinos and pleasant climate.[85][134] It has also become a major banking centre, holding over €100 billion worth of funds.[135] Banks in Monaco specialise in providing private banking, asset and wealth management services.[136] Monaco is the only place in Europe where credit card points are not redeemable. Hotel points are not able to be accumulated nor are transactions recorded, allowing for an increase in privacy that is sought by many of the locals. The principality has successfully sought to diversify its economic base into services and small, high-value-added, non-polluting industries, such as cosmetics.[failed verification][127]

The state retains monopolies in numerous sectors, including tobacco and the postal service. The telephone network (Monaco Telecom) used to be fully owned by the state. Its monopoly now comprises only 45%, while the remaining 55% is owned by Cable & Wireless Communications (49%) and Compagnie Monégasque de Banque (6%). Living standards are high, roughly comparable to those in prosperous French metropolitan areas.[137]

Monaco is not a member of the European Union, but very closely linked via a customs union with France. As such, its currency is the same as that of France, the euro. Before 2002, Monaco minted its own coins, the Monegasque franc. Monaco has acquired the right to mint euro coins with Monegasque designs on its national side.

Gambling industry

The plan for casino gambling was drafted during the reign of Florestan I in 1846. Under Louis-Philippe's petite-bourgeois regime a dignitary such as the Prince of Monaco was not allowed to operate a gambling house.[31] All this changed in the dissolute Second French Empire under Napoleon III. The House of Grimaldi was in dire need of money.

The towns of Menton and Roquebrune, which had been the main sources of income for the Grimaldi family for centuries, were now accustomed to a much-improved standard of living and lenient taxation thanks to the Sardinian intervention and clamoured for financial and political concession, even for separation. The Grimaldi family hoped the newly legal industry would help alleviate the difficulties they faced, above all the crushing debt the family had incurred, but Monaco's first casino would not be ready to operate until after Charles III assumed the throne in 1856.

The grantee of the princely concession (licence) was unable to attract enough business to sustain the operation and, after relocating the casino several times, sold the concession to French casino magnates François and Louis Blanc for 1.7 million francs.

The Blancs had already set up a highly successful casino (in fact the largest in Europe) in Bad-Homburg in the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Homburg, a small German principality comparable to Monaco, and quickly petitioned Charles III to rename a depressed seaside area known as "Les Spelugues (Den of Thieves)" to "Monte Carlo (Mount Charles)."[138] They then constructed their casino in the newly dubbed "Monte Carlo" and cleared out the area's less-than-savoury elements to make the neighbourhood surrounding the establishment more conducive to tourism.

The Blancs opened Le Grand Casino de Monte Carlo in 1858 and the casino benefited from the tourist traffic the newly built French railway system created.[139] Due to the combination of the casino and the railroads, Monaco finally recovered from the previous half-century of economic slump and the principality's success attracted other businesses.[140] In the years following the casino's opening, Monaco founded its Oceanographic Museum and the Monte Carlo Opera House, 46 hotels were built and the number of jewellers operating in Monaco increased by nearly five-fold. In an apparent effort not to overtax citizens, it was decreed that the Monégasque citizens were prohibited from entering the casino unless they were employees.[141] By 1869, the casino was making such a vast sum of money that the principality could afford to end tax collection from the Monegasques—a masterstroke that was to attract affluent residents from all over Europe in a policy that still exists today.

Today, Société des bains de mer de Monaco, which owns Le Grand Casino, still operates in the original building that the Blancs constructed and has since been joined by several other casinos, including the Le Casino Café de Paris, the Monte Carlo Sporting Club & Casino and the Sun Casino. The most recent[when?] addition in Monte Carlo is the Monte Carlo Bay Casino, which sits on 4 hectares of the Mediterranean Sea; among other things, it offers 145 slot machines, all equipped with "ticket-in, ticket-out" (TITO). It is the first Mediterranean casino to use this technology.[142]

Low taxes

Monaco has a 20% VAT plus high social-insurance taxes, payable by both employers and employees. The employers' contributions are between 28% and 40% (averaging 35%) of gross salary, including benefits, and employees pay a further 10% to 14% (averaging 13%).[143]

Monaco has never levied income tax on individuals,[92] and foreigners are thus able to use it as a "tax haven" from their own country's high taxes, because as an independent country, Monaco is not obliged to pay taxes to other countries.[144][145]

The absence of a personal income tax has attracted many wealthy "tax refugee" residents from European countries, who derive the majority of their income from activity outside Monaco. Celebrities, such as Formula One drivers, attract most of the attention but the vast majority are lesser-known business people.[146]

Per a bilateral treaty with France, French citizens who reside in Monaco must still pay income and wealth taxes to France.[147] The principality also actively discourages the registration of foreign corporations, charging a 33 per cent corporation tax on profits unless they can show that at least three-quarters of turnover is generated within Monaco. Unlike classic tax havens, Monaco does not offer offshore financial services.[92]

In 1998, the Centre for Tax Policy and Administration, part of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), issued a first report on the consequences of the financial systems of known tax havens.[148] Monaco did not appear in the list of these territories until 2004, when the OECD became indignant regarding the Monegasque situation and denounced it in a report, along with Andorra, Liechtenstein, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands. The report underlined Monaco's lack of co-operation regarding financial information disclosure and availability.[149][150] Later, Monaco overcame the OECD's objections and was removed from the "grey list" of uncooperative jurisdictions. In 2009, Monaco went a step further and secured a place on the "white list" after signing twelve information exchange treaties with other jurisdictions.[92]

In 2000, the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) stated: "The anti-money laundering system in Monaco is comprehensive. Difficulties have been encountered with Monaco by countries in international investigations on serious crimes that appear to be linked also with tax matters. In addition, the FIU of Monaco (SICCFIN) suffers a great lack of adequate resources. The authorities of Monaco have stated that they will provide additional resources to SICCFIN."[151]

Also in 2000, a report by French politicians Arnaud Montebourg and Vincent Peillon stated that Monaco had relaxed policies with respect to money laundering including within its casino and that the Government of Monaco had been placing political pressure on the judiciary so that alleged crimes were not being properly investigated.[152] In its Progress Report of 2005, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) identified Monaco, along with 36 other territories, as a tax haven,[153] but in its FATF report of the same year it took a positive view of Monaco's measures against money-laundering.[154][155]

The Council of Europe also decided to issue reports naming tax havens. Twenty-two territories, including Monaco, were thus evaluated between 1998 and 2000 on a first round. Monaco was the only territory that refused to perform the second round, between 2001 and 2003, whereas the 21 other territories had planned to implement the third and final round, planned between 2005 and 2007.[156]

In June 2024, the FATF added Monaco to its "grey list", which includes countries needing "increased monitoring" due to statewide issues of money laundering and terrorist financing.[22]

Numismatics

Monaco issued its own coins in various devaluations connected to the écu already in the seventeenth century, but its first decimal coins of the Monégasque franc were issued in 1837 continued until 2001.

Although Monaco is not a European Union member, it is allowed to use the euro as its currency by arrangement with the Council of the European Union; it is also granted the right to use its own designs on the national side of the euro coins, which was introduced in 2002.[157] In preparation for this date, the minting of the new euro coins started as early as 2001. Like Belgium, Finland, France, the Netherlands, and Spain, Monaco decided to put the minting date on its coins. This is why the first euro coins from Monaco have the year 2001 on them, instead of 2002, like the other countries of the Eurozone that decided to put the year of first circulation (2002) on their coins.[158] Three different designs were selected for the Monégasque coins.[159] The design was changed in 2006 after Prince Rainier's death to feature the effigy of Prince Albert.[159]

Demographics

Monaco's total population was 38,400 in 2015, and estimated by the United Nations to be 36,297 as of 1 July 2023.[160][161] Monaco's population is unusual in that the native Monégasques are a minority in their own country: the largest group are French nationals at 28.4%, followed by Monégasque (21.6%), Italian (18.7%), British (7.5%), Belgian (2.8%), German (2.5%), Swiss (2.5%) and U.S. nationals (1.2%).[162] According to 2019 studies, 31% of Monaco's population is reported to be millionaires equalling up to 12,248 individuals

Citizens of Monaco, whether born in the country or naturalised, are called Monégasque. Monaco has the world's highest life expectancy at nearly 90 years.[163][164]

Language

The main and official language of Monaco is French, while Italian is spoken by the principality's sizeable community from Italy. French and Italian are in fact more spoken in the principality today than Monégasque, its historic vernacular language. A variety of Ligurian, Monégasque is not recognised as an official language; nevertheless, some signage appears in both French and Monégasque, and the language is taught in schools. English is also used.

Italian was the official language in Monaco until 1860, when it was replaced by French.[41] This was due to the annexation of the surrounding County of Nice to France following the Treaty of Turin (1860).[41]

The Grimaldi, princes of Monaco, are of Ligurian origin; thus, the traditional national language is Monégasque, a variety of Ligurian, now spoken by only a minority of residents and as a common second language by many native residents. In Monaco-Ville, street signs are printed in both French and Monégasque.[165][166]

Religion

Religion in Monaco according to the Global Religious Landscape survey by the Pew Forum, 2012[3]

Christianity

Christians comprise a total of 86% of Monaco's population.[3]

According to Monaco 2012 International Religious Freedom Report, Roman Catholic Christians are Monaco's largest religious group, followed by Protestant Christians. The Report states that there are two Protestant churches, an Anglican church and a Reformed church. There are also various other Evangelical Protestant communities that gather periodically.

Catholicism

The official religion is Catholicism, with freedom of other religions guaranteed by the constitution.[2] There are five Catholic parish churches in Monaco and one cathedral, which is the seat of the archbishop of Monaco.

The diocese, which has existed since the mid-19th century, was raised to a non-metropolitan archbishopric in 1981 as the Archdiocese of Monaco and remains exempt (i.e. immediately subject to the Holy See). The patron saint is Saint Devota.

Anglican Communion

There is one Anglican church (St Paul's Church), located in the Avenue de Grande Bretagne in Monte Carlo. The church was dedicated in 1925. In 2007 this had a formal membership of 135 Anglican residents in the principality but was also serving a considerably larger number of Anglicans temporarily in the country, mostly as tourists. The church site also accommodates an English-language library of over 3,000 books.[167] The church is part of the Anglican Diocese in Europe.

Reformed Church of Monaco

There is one Reformed church, which meets in a building located in Rue Louis Notari. The building dates from 1958 to 1959. The church is affiliated with the United Protestant Church of France (Église Protestante Unie de France, EPUF), a group that incorporates the former Reformed Church of France (Église Réformée de France). Through this affiliation with EPUF, the church is part of the World Communion of Reformed Churches. The church acts as a host church to some other Christian communities, allowing them to use its building.

Charismatic Episcopal Church

The Monaco Parish of the Charismatic Episcopal Church (Parish of St Joseph) dates from 2017 and meets in the Reformed Church's Rue Louis Notari building.

Christian Fellowship

The Monaco Christian Fellowship, formed in 1996, meets in the Reformed Church's Rue Louis Notari building.

Greek Orthodoxy

Monaco's 2012 International Religious Freedom Report states that there is one Greek Orthodox church in Monaco.

Russian Orthodox

The Russian Orthodox Parish of the Holy Royal Martyrs meets in the Reformed Church's Rue Louis Notari building.

Hinduism

According to the Monaco Statistics database (IMSEE), there are around 100 Hindus living in the country.[168]

Judaism

The Association Culturelle Israélite de Monaco (founded in 1948) is a converted house containing a synagogue, a community Hebrew school, and a kosher food shop, located in Monte Carlo.[169] The community mainly consists of retirees from Britain (40%) and North Africa. Half of the Jewish population is Sephardic, mainly from North Africa, while the other half is Ashkenazi.[170]

Islam

The Muslim population of Monaco consists of about 280 people, most of whom are residents, not citizens.[171] The majority of the Muslim population of Monaco are Arabs, though there is a Turkish minority as well.[172] Monaco does not have any official mosques.[173]

Sports

Two important sports for Monaco are football and racing, but there are a number of other sports played;sports are also a part of Monaco's economy and culture.

Formula One

Since 1929, the Monaco Grand Prix has been held annually in the streets of Monaco.[174] It is widely considered to be one of the most prestigious automobile races in the world. The erection of the Circuit de Monaco takes six weeks to complete and the removal after the race takes another three weeks.[174]

The circuit is narrow and tight and its tunnel, tight corners and many elevation changes make it perhaps the most demanding Formula One track.[175] Driver Nelson Piquet compared driving the circuit to "riding a bicycle around your living room".

Despite the challenging nature of the course it has only had two fatalities, Luigi Fagioli who died from injuries received in practice for the 1952 Monaco Grand Prix (run to sports car regulations that year, not Formula 1)[176] and Lorenzo Bandini, who crashed, burned and died three days later from his injuries in 1967.[177] Two other drivers had lucky escapes after they crashed into the harbour, the most famous being Alberto Ascari in the 1955 Monaco Grand Prix and Paul Hawkins, during the 1965 race.[174]

In 2020, the Monaco Grand Prix was cancelled for the first time since 1954 because of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Monégasque Formula 1 drivers

There have been five Formula One drivers from Monaco:

- Charles Leclerc (2018–present) Winner of the 2024 Monaco Grand Prix

- Robert Doornbos (2005, Dutch driver under a Monégasque licence)

- Olivier Beretta (1994)

- André Testut (1958–1959)

- Louis Chiron (1950–1958) Winner of the 1931 Monaco Grand Prix

Formula E

Starting in 2015 Formula E started racing biennially with the Historic Grand Prix of Monaco on the Monaco ePrix[178] and used a shorter configuration of the full Formula 1 circuit, keeping it around Port Hercules until 2021.

ROKiT Venturi Racing is the only motor racing team based in the principality, headquartered in Fontvieille.[179] The marque competes in Formula E and was one of the founding teams of the fully-electric championship. Managed by former racing drivers Susie Wolff (CEO) and Jérôme d'Ambrosio (Team Principal),[180] the outfit holds 16 podiums in the series to date including five victories. 1997 Formula One World Champion Jacques Villeneuve and eleven-time Formula One race winner Felipe Massa have raced for the team previously.[181][182] Ten-time Macau winner and 2021 vice World Champion Edoardo Mortara and Season 3 Formula E champion Lucas di Grassi currently race for the team.[183]

Monte Carlo Rally

Since 1911 part of the Monte Carlo Rally has been held in the principality, originally held at the behest of Prince Albert I. Like the Grand Prix, the rally is organised by Automobile Club de Monaco. It has long been considered to be one of the toughest and most prestigious events in rallying and from 1973 to 2008 was the opening round of the World Rally Championship (WRC).[184] From 2009 until 2011, the rally served as the opening round of the Intercontinental Rally Challenge.[185] The rally returned to the WRC calendar in 2012 and has been held annually since.[186] Due to Monaco's limited size, all but the ending of the rally is held on French territory.

Football

Monaco hosts two major football teams in the principality: the men's football club, AS Monaco FC, and the women's football club, OS Monaco. AS Monaco plays at the Stade Louis II and competes in Ligue 1, the first division of French football. The club is historically one of the most successful clubs in the French league, having won Ligue 1 eight times (most recently in 2016–17) and competed at the top level for all but six seasons since 1953. The club reached the 2004 UEFA Champions League Final, with a team that included Dado Pršo, Fernando Morientes, Jérôme Rothen, Akis Zikos and Ludovic Giuly, but lost 3–0 to Portuguese team FC Porto. French World Cup-winners Thierry Henry, Fabien Barthez, David Trezeguet, and Kylian Mbappe have played for the club. The Stade Louis II also played host to the annual UEFA Super Cup from 1998 to 2012 between the winners of the UEFA Champions League and the UEFA Europa League.

The women's team, OS Monaco, competes in the women's French football league system. The club plays in the local regional league, deep down in the league system. It once played in the Division 1 Féminine, in the 1994–95 season, but was quickly relegated.

The Monaco national football team represents the nation in association football and is controlled by the Monégasque Football Federation, the governing body for football in Monaco. Monaco is one of two sovereign states in Europe (along with the Vatican City) that is not a member of UEFA and so does not take part in any UEFA European Football Championship or FIFA World Cup competitions. They are instead affiliated with CONIFA, where they compete against other national teams that are not FIFA members. The team plays its home matches in the Stade Louis II.

Rugby

Monaco's national rugby team, as of April 2019, is 101st in the World Rugby Rankings.[187]

Basketball

Multi-sport club AS Monaco owns AS Monaco Basket which was founded in 1928. They play in the top-tier European basketball league, the EuroLeague, and the French top flight, the LNB Pro A. They have three Pro A Leaders Cup, two Pro B (2nd-tier), and one NM1 (3rd-tier) championship. They play in Salle Gaston Médecin, which is part of Stade Louis II.

Professional boxing

Due in part to its position both as a tourist and gambling centre, Monaco has staged major professional boxing world title and non-title fights from time to time; those include the Carlos Monzon versus Nino Benvenuti rematch,[188] Monzon's rematch with Emile Griffith,[189] Monzon's two classic fights with Rodrigo Valdes,[190][191] Davey Moore versus Wilfredo Benitez,[192] the double knockout-ending classic between Lee Roy Murphy and Chisanda Mutti (won by Murphy),[193] and Julio César Chávez Sr. versus Rocky Lockridge.[194] All of the aforementioned contests took place at the first Stade Louis II or the second Stade Louis II stadiums.

Other sports and events

The Monte-Carlo Masters is held annually in neighbouring Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France, as a professional tournament for men as part of tennis's ATP Masters Series.[195] The tournament has been held since 1897. Golf's Monte Carlo Open was also held at the Monte Carlo Golf Club at Mont Agel in France between 1984 and 1992.

Monaco has a national Davis Cup team, which plays in the European/African Zone.

Monaco has also competed in the Olympic Games, although, no athlete from Monaco has ever won an Olympic medal. At the Youth Olympic Winter Games, Monaco won a bronze medal in bobsleigh.

The 2009 Tour de France, the world's premier cycle race, started from Monaco with a 15 km (9 mi) closed-circuit individual time trial starting and finishing there on the first day, and the 182 km (113 mi) second leg starting there on the following day and ending in Brignoles, France.[196]

Monaco has also staged part of the Global Champions Tour (International Show-jumping).[197] In 2009, the Monaco stage of the Global Champions tour took place between 25 and 27 June.

The Monaco Marathon is the only marathon in the world to pass through three countries, those of Monaco, France and Italy, before the finish at the Stade Louis II.

The Monaco Ironman 70.3 triathlon race is an annual event with over 1,000 athletes competing and attracts top professional athletes from around the world. The race includes a 1.9 km (1.2 mi) swim, 90 km (56 mi) bike ride and 21.1 km (13.1 mi) run.

Since 1993, the headquarters of the International Association of Athletics Federations,[198] the world governing body of athletics, is located in Monaco.[199] An IAAF Diamond League meet is annually held at Stade Louis II.[200]

A municipal sports complex, the Rainier III Nautical Stadium in the Port Hercules district consists of a heated saltwater Olympic-size swimming pool, diving boards and a slide.[201] The pool is converted into an ice rink from December to March.[201]

In addition to Formula One, the Circuit de Monaco hosts several support series, including FIA Formula 2, Porsche Supercup and Formula Regional Europe.[202] It has in the past also hosted Formula Three and Formula Renault.

From 10 to 12 July 2014 Monaco inaugurated the Solar1 Monte Carlo Cup, a series of ocean races exclusively for solar-powered boats.[203],[204]

The women team of the chess club CE Monte Carlo won the European Chess Club Cup several times.

Culture

Cuisine

The cuisine of Monaco is a Mediterranean cuisine shaped by the cooking style of Provence and the influences of nearby northern Italian and southern French cooking, in addition to Monaco's own culinary traditions.[205]

Two famous restaurants in Monaco include the Le Lous XV, currently with three Michelin stars, and the Café de Paris. The Café de Paris is next to the Casino and first opened in 1868, though it has been renovated several times over its lifetime.

Music

Monaco has an opera house, a symphony orchestra and a classical ballet company. Monaco participated regularly in the Eurovision Song Contest between 1959–1979 and 2004–2006, winning in 1971, although none of the artists participating for the principality was originally Monegasque. French-born Minouche Barelli, however, acquired Monegasque citizenship in 2002, 35 years after her representing the principality in 1967.[206]

Visual arts

Monaco has a national museum of contemporary visual art at the New National Museum of Monaco. In 1997, the Audiovisual Institute of Monaco was founded aimed to preserve audiovisual archives and show how the Principality of Monaco is represented in cinema. The country also has numerous works of public art, statues, museums, and memorials (see list of public art in Monaco).

Museums in Monaco

Events, festivals, and shows

The Principality of Monaco hosts major international events such as :

Bread Festival

Monaco also has an annual bread festival on 17 September every year.[207]

Parks and Gardens

There is several gardens in Monaco, which are in a variety of styles and purpose. There is an exotic plant garden, Saint Martin garden, African plants garden, Casino Gardens, Princess Grace Rose Garden, and a Japanese Gardens.[208]

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Monaco has ten state-operated schools, including: seven nursery and primary schools; one secondary school, Collège Charles III;[209] one lycée that provides general and technological training, Lycée Albert 1er;[210] and one lycée that provides vocational and hotel training, Lycée technique et hôtelier de Monte-Carlo.[211] There are also two grant-aided denominational private schools, Institution François d'Assise Nicolas Barré and Ecole des Sœurs Dominicaines, and one international school, the International School of Monaco,[212][213] founded in 1994.[214]

Colleges and universities

There is one university located in Monaco, namely the International University of Monaco (IUM), an English-language university specialising in business education and operated by the Institut des hautes études économiques et commerciales (INSEEC) group.

Flag

The flag of Monaco is one of the world's oldest national flag designs.[215] Adopted by Monaco on 4 April 1881 its based on the Monaco Royal colors going back to the 14th century.[216]

The flag has similarities to the flags of German state of Hesse, Thuringia, Indonesia, Singapore, and Poland in the modern times.[217]

-

Coat of Arms

-

Blason

-

Flag

Transport

The Monaco-Monte Carlo station is served by the SNCF, the French national rail system. The Monaco Heliport provides helicopter service to the closest airport, Côte d'Azur Airport in Nice, France.

The Monaco bus company (CAM) covers all the tourist attractions, museums, Exotic garden, business centres, and the Casino or the Louis II Stadium.[218]

There is about 77 km (48 miles) of roads in Monaco, many sections of which are also used for automotive and other races.[219]

The main port is Port Hercules which includes a deep-water pier, and there is another smaller harbor between the Rock and Fontvieille.

Relations with other countries

Monaco is so old that it has outlived many of the nations and institutions that it has had relations with. The Crown of Aragon and Republic of Genoa became a part of other countries, as did the Kingdom of Sardinia. Honoré II, Prince of Monaco secured recognition of his independent sovereignty from Spain in 1633, and then from Louis XIII of France by the Treaty of Péronne (1641).

Monaco made a special agreement with France in 1963 in which French customs laws apply in Monaco and its territorial waters.[147] Monaco uses the euro but is not a member of the European Union.[147] Monaco shares a 6 km (3.7 mi) border with France but also has about 2 km (1.2 mi) of coastline with the Mediterranean sea.[220] Two important agreements that support Monaco's independence from France include the Franco-Monégasque Treaty of 1861 and the French Treaty of 1918 (see also Kingdom of Sardinia). The United States CIA Factbook records 1419 as the year of Monaco's independence.[220]

France and Italy have embassies within Monaco, while most other nations represented via operations in Paris.[221][222] There are about another 30 or so consulates.[221] By the 21st century Monaco maintained embassies in Belgium (Brussels), France (Paris), Germany (Berlin), the Vatican, Italy (Rome), Portugal (Lisbon),[223] Spain (Madrid), Switzerland (Bern), United Kingdom (London) and the United States (Washington).[221]

As of 2000[update] nearly two-thirds of the residents of Monaco were foreigners.[224] In 2015 the immigrant population was estimated at 60%[220] It is reported to be difficult to gain citizenship in Monaco, or at least in relative number there are not many people who do so. In 2015 an immigration rate of about 4 people per 1,000 was noted, or about 100–150 people a year.[225] The population of Monaco went from 35,000 in 2008 to 36,000 in 2013, and of that about 20 per cent were native Monegasque[226] (see also Nationality law of Monaco).

A recurring issue Monaco encounters with other countries is the attempt by foreign nationals to use Monaco to avoid paying taxes in their own country.[220] Monaco actually collects a number of taxes including a 20% VAT and 33% on companies unless they make over 75% of their income inside Monaco.[220] Monaco does not allow dual citizenship but does have multiple paths to citizenship including by declaration and naturalisation.[227] In many cases the key issue for obtaining citizenship, rather than attaining residency in Monaco, is the person's ties to their departure country.[227] For example, French citizens must still pay taxes to France even if they live full-time in Monaco unless they resided in the country before 1962 for at least 5 years.[227] In the early 1960s there was some tension between France and Monaco over taxation.[228]

There are no border formalities entering or leaving France. For visitors, a souvenir passport stamp is available on request at Monaco's tourist office. This is located on the far side of the gardens that face the Casino.

| Microstate | Association Agreement | Eurozone[229] | Schengen Area | EU single market | EU customs territory[230] | EU VAT area[231] | Dublin Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negotiating[232] | Yes[d] | De facto[e] | Partial[f] | Yes[g] | Yes[h][i] | No |

See also

Notes

- ^ /ˈmɒnəkoʊ/ MON-ə-koh; French: [mɔnako]; Italian: [ˈmɔːnako]; Monégasque: Mùnegu [ˈmuneɡu]; Occitan: Mónegue [ˈmuneɣe]

- ^ French: Principauté de Monaco; Monégasque: Prinçipatu de Mùnegu; Ligurian: Prinçipato de Mónego; Occitan: Principat de Mónegue; Italian: Principato di Monaco.

- ^ For further information, see languages of Monaco.

- ^ Monetary agreement with the EU to issue euros

- ^ Although not a contracting party to the Schengen Agreement, has an open border with France and Schengen laws are administered as if it were a part of France.[233][234]

- ^ Through an agreement with France[235]

- ^ Through an agreement with France. Part of the EU Customs territory, administered as part of France.[233][236][237][238]

- ^ Also part of the EU excise territory[238]

- ^ Through an agreement with France. Administered as a part of France for taxation purposes.[231][233][238][239]

References

- ^ "Constitution de la Principauté". Council of Government. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- ^ a b ."Constitution de la Principaute". Principaute De Monaco: Ministère d'Etat (in French). Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

Art. 9. - La religion catholique, apostolique et romaine est religion d'Etat.

- ^ a b c "The Global Religious Landscape" (PDF). Pewforum.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Embassy of Monaco in Washington D.C. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ "Monaco in Figures 2024". monacostatistics.mc. Monaco Statistics. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "Population census". monacostatistics.mc. Monaco Statistics. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ a b "EUROPE :: MONACO". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "GDP (current US$) - Monaco". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "GDP per capita (current US$) - Monaco". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "What side of the road do people drive on?". Whatsideoftheroad.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Population, total". World Bank. Archived from the original on 20 February 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ "Demography / Population and employment / IMSEE - Monaco IMSEE". www.monacostatistics.mc. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ "The 1.25-mile waterfront stretch in Monaco that used to be the world's most expensive street looks no different from the rest of the city". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Monaco Is The Most Expensive Place To Buy Property In The World". Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Monaco Statistics / IMSEE — Monaco IMSEE". Imsee.mc (in French). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ "Ventimiglia - Principato di Monaco". www.distanza.org. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ "Communiqué de la Direction des Services Judiciaires". Government of Monaco (in French). 26 June 2019. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ In fact Francesco Grimaldi, who captured the Rock on the night of 8 January 1297, was forced to flee Monaco only four years after the fabled raid, never to come back. The Grimaldi family was not able to permanently secure their holding until 1419 when they purchased Monaco, along with two neighbouring villages, Menton and Roquebrune. Source: Edwards, Anne (1992). The Grimaldis of Monaco: The Centuries of Scandal – The Years of Grace. William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-08837-8.

- ^ "Monte Carlo: The Birth of a Legend". SBM Group. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ Beck, Katie. "The country running out of space for its millionaires". www.bbc.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Bourgery-Gonse, Théo (23 January 2023). "Monaco's anti-money laundering system inadequate, risks name-and-shame". Euractiv. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Monaco added to money laundering 'gray list'". Deutsche Welle. 28 June 2024. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ "Monaco's Prince Albert II: Oceans are a 'family heritage,' with little time to save them". Los Angeles Times. 13 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ "Ocean Acidification International Coordination Centre (OA-ICC)" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ "Division of IAEA Marine Environment Laboratories (NAML)". www.iaea.org. 8 June 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ "μόνος". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library - ^ "οἶκος". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library - ^ "History of Monaco". Monaco-montecarlo.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Strabo, Geography, Gaul, 4.6.3 at LacusCurtious

- ^ "μόνοικος". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library - ^ a b c "Monaco". State.gov. 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco Life". 26 July 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco history". Visitmonaco.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Histoire de Monaco, famille Grimaldi | Monte-Carlo SBM". Fr.montecarlosbm.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ a b "The Mediterranean Empire of the Crown of Aragon". explorethemed.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Monaco – The Principality of Monaco". Monaco.me. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ a b "The History Of Monaco". Monacoangebote.de. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco: History". monaco.mc. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ a b "Important dates – Monaco Monte-Carlo". Monte-carlo.mc. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ a b "24 X 7". Infoplease.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ a b c "Il monegasco, una lingua che si studia a scuola ed è obbligatoria" (in Italian). 15 September 2014. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ "History of the Principality of Monaco – Access Properties Monaco – Real-estate Agency Monaco". Access Properties Monaco. Archived from the original on 9 August 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "History of Monaco". Monacodc.org. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Histoire de la Principauté – Monaco – Mairie de Monaco". Monaco-mairie.mc. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "MONACO". Tlfq.ulaval.ca. Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco timeline". BBC News. 28 March 2012. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco History, History of Monaco – Allo' Expat Monaco - World War II". Monaco.alloexpat.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Abramovici P. Un rocher bien occupé : Monaco pendant la guerre 1939–1945 Editions Seuil, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-02-037211-8

- ^ "Monaco histoire". Tmeheust.free.fr. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco – Principality of Monaco – Principauté de Monaco – French Riviera Travel and Tourism". Nationsonline.org. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "The 1963 Franco-Monegasque tax treaty". Archived from the original on 12 March 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Monaco". The World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "History of Monaco. Monaco chronology". Europe-cities.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco Military 2012, CIA World Factbook". Theodora.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco Royal Family". Yourmonaco.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Biography". Palais.mc. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "History of Monaco, Grimaldi family". Monte-Carlo SBM. Archived from the original on 12 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Williams, Carol J. (27 August 2015). "More than seven decades later, Monaco apologises for deporting Jews". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 30 August 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Monaco land reclamation project gets green light". rivieratimes.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ a b Colin Randall (23 May 2013). "Monaco €1 billion reclamation plan for luxury homes district". thenational.ae. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ a b c "Monaco's New Marina, in 10 Years from now". mooringspot.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ "Forbes Life". forbes.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Gouvernement Monaco [@GvtMonaco] (28 February 2020). "[#Coronavirus] Les autorités sanitaires de la Principauté ont été informées qu'une personne prise en charge dans la matinée et conduite au Centre Hospitalier Princesse Grace était positive au COVID 19.Son état de santé n'inspire pas d'inquiétude" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Bulant, Jeanne (29 February 2020). "Coronavirus: un premier cas de contamination détecté à Monaco et transféré au CHU de Nice". BFMTV (in French). Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Bongiovanni, Francesco M. (5 September 2020). "Historical launch on Sept. 2nd, 2020: The first satellite from Monaco is now orbiting the earth". Orbital Solutions. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ July 2, 2024 Monaco Welcomes The Tour de France: A Historic Return After 15 Years Frances Landrum

- ^ "Monaco". State.gov. 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "Politics". Monaco-IQ. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco: Government". GlobalEdge.msu.edu. 4 October 2004. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monaco". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Schminke, Tobias Gerhard (7 February 2023). "Single alliance wins all seats in 'historic' Monaco election". Euractiv. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Deux listes pour une mairie". Monaco Hebdo. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ Mairie de Monaco. "Les élus". La Mairie de Monaco. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ "Le Conseil Communal – Mairie de Monaco". La Mairie de Monaco. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ "Élections communales à Monaco: vingt-quatre candidats en lice". nicematin.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ La justice à Monaco Archived 2 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine: "Les deux chefs de la cour d'appel, le premier président et le procureur général, sont des magistrats français."

- ^ "Security in Monaco". Monte-carlo.mc. 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 6 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Division de Police Maritime et Aéroportuaire". Gouv.mc (in French). 16 August 1960. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "The Palace Guards – Prince's Palace of Monaco". Palais.mc. 27 January 2011. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Présentation". Corps des sapeurs-pompiers de Monaco. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "Compagnie des Carabiniers du Prince". Gouv.mc (in French). Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Monaco Districts". Monaco.me. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ a b Monaco, Government of. ""monaco statistics pocket" / Publications / IMSEE - Monaco IMSEE". Monacostatistics.mc. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ "Geography and Map of Monaco". mapofeurope.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Monaco's Areas / Monaco Official Site". Visitmonaco.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Observatoire Cave, Monaco". Mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024.

- ^ Highest point at ground level (Access to Patio Palace on D6007) "Monaco Statistics pocket – Edition 2014" (PDF). Monaco Statistics – Principality of Monaco. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "Highest and lowest points in countries islands oceans of the world". Worldatlas.com. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ "Monaco". Google Maps. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Plan General De La Principaute De Monaco" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ a b Robert BOUHNIK (19 October 2010). "Home > Files and Reports > Public works > 2002 Archives — Extension of "La Condamine Port"(Gb)". Cloud.gouv.mc. Retrieved 22 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Samuel, Henry (28 December 2009). "Monaco to build into the sea to create more space". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ Robert Bouhnik (19 October 2010). "Home > Files and Reports > Public works(Gb)". Cloud.gouv.mc. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "Royal Opinions – Social, Political, & Economical Affairs of Monaco". Royalopinions.proboards.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "Monaco remet sur le tapis le projet d'extension en mer". Econostrum.info. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Presentation". Ports-monaco.com. 1 January 2006. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Prince Albert of Monaco interview on fishing issues". YouTube. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ "Mareterra Land Extension Monaco | le Portier Cove New Development | Savills Monaco". 24 July 2017.

- ^ Robertson, Alex (1 February 2012). "The 10 smallest countries in the world". Gadling.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Population Density". Geography.About.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "History « Consulate General of Monaco". Monaco-Consulate.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "About Monaco". JCI EC 2013. 3 March 2010. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Monte Carlo". Monte Carlo. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "West 8 Urban Design & Landscape Architecture / projects / Cape Grace, Monaco". West8.nl. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "The new Monaco skyline". CityOut Monaco. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ Samuel, Henry (28 December 2009). "Monaco to build into the sea to create more space". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Prince speaks of future developments". CityOut Monaco. 29 December 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Dictionary – Definition of Larvotto". Websters-Online-Dictionary.org. 1 March 2008. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ^ "Tourist Board Official Website". Visitmonaco.com. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2012.