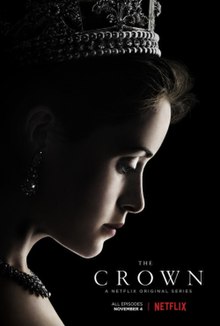

The Crown season 1

| The Crown | |

|---|---|

| Season 1 | |

Promotional poster | |

| Starring | |

| No. of episodes | 10 |

| Release | |

| Original network | Netflix |

| Original release | 4 November 2016 |

| Season chronology | |

The first season of The Crown follows the life and reign of Queen Elizabeth II. It consists of ten episodes and was released on Netflix on 4 November 2016.

Claire Foy stars as Elizabeth, with main cast members Matt Smith, Vanessa Kirby, Eileen Atkins, Jeremy Northam, Victoria Hamilton, Ben Miles, Greg Wise, Jared Harris, John Lithgow, Alex Jennings, and Lia Williams.

Premise

[edit]The Crown traces the life of Queen Elizabeth II from her wedding in 1947 through the wedding of Charles and Camilla in 2005.[1]

The first season, in which Claire Foy portrays the Queen in the early part of her reign, depicts events up to 1955, taking in the death of King George VI, prompting Elizabeth’s accession to the throne, and leading up to the resignation of Winston Churchill as prime minister and the Queen's sister Princess Margaret deciding not to marry Peter Townsend.[2]

Cast

[edit]Main

[edit]- Claire Foy as Princess Elizabeth and later Queen Elizabeth II[1]

- Matt Smith as Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Elizabeth's husband[1]

- Vanessa Kirby as Princess Margaret, Elizabeth's younger sister[1]

- Eileen Atkins as Queen Mary, Elizabeth's grandmother and great-granddaughter of King George III[3]

- Jeremy Northam as Anthony Eden, Churchill's Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary, who succeeds him as Prime Minister[4]

- Victoria Hamilton as Queen Elizabeth, King George VI's wife and Elizabeth II's mother, known as Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother during her daughter's reign[1]

- Ben Miles as Group Captain Peter Townsend, George VI's equerry, who hopes to marry Princess Margaret[5]

- Greg Wise as Lord Mountbatten, Philip's ambitious uncle and great-grandson of Queen Victoria

- Jared Harris as King George VI, Elizabeth's father, known to his family as Bertie[1]

- John Lithgow as Sir Winston Churchill, the Queen's first Prime Minister[1]

- Alex Jennings as Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor, formerly King Edward VIII, who abdicated in favour of his younger brother Bertie to marry Wallis Simpson; known to his family as David[6]

- Lia Williams as Wallis, Duchess of Windsor, Edward's American wife[6]

Featured

[edit]The following actor is credited in the opening titles of a single episode:

- Stephen Dillane as Graham Sutherland, a noted artist who paints a portrait of the ageing Churchill

Recurring

[edit]- Verity Russell as young Princess Elizabeth

- Beau Gadsdon as young Princess Margaret

- Billy Jenkins as young Prince Charles, Elizabeth and Philip's son

- Grace and Amelia Gilmour as young Princess Anne, Elizabeth and Philip's daughter[7] (uncredited)

- Clive Francis as Lord Salisbury, Leader of the House of Lords

- Pip Torrens as Tommy Lascelles, Private Secretary to King George VI; later Private Secretary to the Queen

- Harry Hadden-Paton as Martin Charteris, Private Secretary to Princess Elizabeth; later Assistant Private Secretary to the Queen

- Daniel Ings as Mike Parker, Private Secretary to the Duke of Edinburgh

- Lizzy McInnerny as Margaret "Bobo" MacDonald, Principal Dresser to the Queen

- Patrick Ryecart as the Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal and Chief Butler of England

- Will Keen as Michael Adeane, Assistant Private Secretary to the Queen; later Private Secretary to the Queen

- James Laurenson as Doctor Weir, Physician to King George VI; later Physician to the Queen

- Mark Tandy as Cecil Beaton, Court Photographer to the British Royal Family

- Harriet Walter as Clementine Churchill, Winston Churchill's wife[4]

- Nicholas Rowe as Jock Colville, Sir Winston Churchill's private secretary[3]

- Simon Chandler as Clement Attlee, Former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

- Kate Phillips as Venetia Scott, Sir Winston Churchill's secretary

- Ronald Pickup as Geoffrey Fisher, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Nigel Cooke as Harry Crookshank, Minister of Health

- Patrick Drury as The Earl of Scarbrough, Lord Chamberlain

- John Woodvine as Cyril Garbett, Archbishop of York

- Rosalind Knight as Princess Alice, Philip's mother

- Andy Sanderson as Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, Elizabeth's paternal uncle (also Edward VIII and George VI's brother)[3]

- Michael Culkin as Rab Butler, Chairman of the Conservative Party

- George Asprey as Walter Monckton, Minister of Defence

- James Hillier as Equerry

- Jo Stone-Fewings as Collins

- Anna Madeley as Clarissa Eden, Anthony Eden's wife (and Sir Winston Churchill's niece)

- Tony Guilfoyle as Michael Ramsey, Bishop of Durham; later Archbishop of York

- Nick Hendrix as Billy Wallace, Princess Margaret's close friend

- Josh Taylor as Johnny Dalkeith, Princess Margaret's close friend (also the Duchess of Gloucester's nephew)

- David Shields as Colin Tennant, Princess Margaret's close friend; later Lady Anne Coke's fiancé[8]

- Paul Thornley as Bill Mattheson

Guest

[edit]- Michael Bertenshaw as Sir Piers Legh, Master of the Household

- Julius D'Silva as Baron Nahum, Court Photographer to the British Royal Family

- Alan Williams as Professor Hogg, the Queen's tutor

- Michael Cochrane as Henry Marten, Vice-Provost of Eton and the Queen's private tutor

- Jo Herbert as Mary Charteris, Martin Charteris's wife

- Richard Clifford as Norman Hartnell, Royal Warrant as Dressmaker to the Queen

- Joseph Kloska as Henry ‘Porchey’ Herbert, Lord Porchester, Racing Manager to the Queen

- Andrea Deck as Jean Wallop, Porchey's fiancée; later Jean, Lady Porchester

- Amir Boutrous as Gamal Abdel Nasser, President of Egypt

- Abigail Parmenter as Judy Montagu, close friend of Princess Margaret

Episodes

[edit]| No. overall | No. in season | Title | Directed by | Written by | Original release date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | "Wolferton Splash" | Stephen Daldry | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark renounces his titles and citizenship and takes the name Philip Mountbatten before marrying Princess Elizabeth, eldest daughter and heir presumptive of King George VI. The newlyweds take up residence in Malta, where Philip rises through the ranks of the Royal Navy while Elizabeth gives birth to their son Charles and their daughter Anne. Years later, the family returns to London to be with George as he undergoes a lung operation. George receives a terminal diagnosis, prompting him to confide in newly re-elected Conservative Prime Minister Winston Churchill and counsel Philip on how to assist Elizabeth when she becomes the new sovereign. | ||||||

| 2 | 2 | "Hyde Park Corner" | Stephen Daldry | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

With George in ill health, Elizabeth and Philip tour the Commonwealth in his place, making their first stop in Nairobi, Kenya. Several Cabinet members express growing concerns over Churchill's ability to govern, prompting Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden to ask George if he can persuade Churchill to step down. George declines, stating that Churchill will step down when the right time comes. After an evening spent singing with youngest daughter Margaret and watching a news report on Elizabeth and Philip's arrival in Kenya, George dies in his sleep. News spreads around the world after his body is discovered the following morning. Elizabeth and Philip return to London, where Elizabeth assumes the role of sovereign. | ||||||

| 3 | 3 | "Windsor" | Philip Martin | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

On 10 December 1936, Edward VIII, George's elder brother and predecessor, abdicates the throne to marry twice-divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson. Despite protests from Queen Mary, Edward makes a radio broadcast from Windsor Castle, informing the British people of his reasons for abdicating before declaring his allegiance for George. In the present, amidst preparations for George's funeral, Edward reenters the country for the first time in nearly twenty years, with Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother expressing anger at how his actions caused irreparable damage to the monarchy. Elizabeth meets Churchill to discuss Philip's requests to let Charles and Anne keep the Mountbatten surname and let the family continue living at Clarence House rather than move into Buckingham Palace. Churchill is reluctant to agree, and Elizabeth drops both matters after receiving counsel from Edward. She later learns her coronation has been set for the following year, recognising it as a deliberate move by Churchill to secure his position within the Conservative Party. Philip approaches Peter Townsend, George's former equerry, and convinces him to give flying lessons, unaware that Townsend is having an affair with Margaret. | ||||||

| 4 | 4 | "Act of God" | Julian Jarrold | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

On 5 December 1952, a great smog forms over London, reducing visibility, killing thousands, and hospitalising thousands more over the course of several days. Elizabeth's advisors pressure her to ask Churchill, who refers to the event as an "act of God", to step down. Reluctant, Elizabeth summons him for a private audience after he has come under fire for refusing to discuss the smog at Cabinet. Beforehand, Churchill has learned that his secretary, Venetia Scott, was killed by a double-decker bus. He later makes an impassioned speech, promising a longer-term approach to prevent future smog. Both the speech and the smog's sudden disappearance prompt Elizabeth to change her mind as Churchill arrives at the Palace. Having colluded with Downing Street staff to use the crisis to attempt to open a vote of no confidence in Churchill, Clement Attlee dejectedly learns of the Queen's change of heart. | ||||||

| 5 | 5 | "Smoke and Mirrors" | Philip Martin | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

On 11 May 1937, Elizabeth helps her father rehearse for his coronation. In the present, while visiting London to spend time with an ailing Queen Mary, Edward clashes with Private Secretary Tommy Lascelles after learning that he and Wallis are not invited to attend the coronation. Elizabeth regrets her decision to place Philip in charge of preparations after he upsets her with a request that he should forgo kneeling to pay homage when she is crowned and irritates the committee by insisting that they televise the event. On 2 June 1953, Elizabeth is crowned at Westminster Abbey while Edward and Wallis mockingly view the coverage from their Paris villa. Eventually, Wallis watches as Edward tearfully plays the bagpipes outside. | ||||||

| 6 | 6 | "Gelignite" | Julian Jarrold | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

When Margaret and Townsend ask to get married, Elizabeth promises her support, while Lascelles and the Queen Mother advise against it. A newspaper publishes an article about the relationship and, after learning that the Royal Marriages Act of 1772 prohibits Margaret from marrying without permission until she turns twenty-five, Elizabeth changes her mind. Elizabeth and Philip take Townsend, who is set to be posted to Brussels, with them on a trip to Northern Ireland, but his sudden popularity causes Lascelles to recommend he be posted sooner than promised. | ||||||

| 7 | 7 | "Scientia Potentia Est" | Benjamin Caron | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

In August 1953, after discovering that the Soviet Union has tested their first thermonuclear weapon, Churchill urges an international summit with American President Eisenhower. At the last minute, Churchill suffers a stroke, which inhibits his ability to govern and prompts Lord Salisbury to keep his ailment secret. Meanwhile, Elizabeth chooses to replace the retiring Lascelles with senior deputy Michael Adeane, after Lascelles strongly disapproves of her preferred choice of Martin Charteris. Realising that she did not receive a proper education growing up as a princess, she engages a private tutor to improve her studies, which helps her gain the courage to dress down both Churchill and Salisbury after Jock Colville accidentally reveals their deception. | ||||||

| 8 | 8 | "Pride & Joy" | Philip Martin | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

With Elizabeth and Philip touring the Commonwealth, Margaret takes on more engagements. Meanwhile the Queen Mother travels to Scotland to reflect on her new position and buys a castle. Philip grows frustrated with Elizabeth using him as a prop, resulting in a confrontation that is recorded by photographers. While Elizabeth convinces them to surrender their recordings, she and Philip are unable to resolve their argument. Churchill visits Margaret and refuses to let her continue taking on engagements, saying that the British people do not want someone with passion or personality. | ||||||

| 9 | 9 | "Assassins" | Benjamin Caron | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

Philip begins spending more time away from the Palace while Elizabeth begins spending time with her horse-racing manager and friend Lord "Porchey" Porchester. Tension escalates after Elizabeth orders a direct line to be installed for Porchey. Elizabeth later tells Philip that he is the only man she has ever loved, prompting him to mouth an apology after she makes a speech at Churchill's eightieth birthday dinner. Churchill meets with artist Graham Sutherland after Parliament commissions him to paint a birthday portrait. Upon receiving the portrait, Churchill confronts Sutherland about its accuracy, eventually admitting his pain at what ageing has done to him. Churchill resigns and requests that Eden replace him as Prime Minister, while Clementine orders that the portrait be destroyed. | ||||||

| 10 | 10 | "Gloriana" | Philip Martin | Peter Morgan | 4 November 2016 | |

|

Elizabeth finds herself torn when the country is divided over Margaret's relationship with Townsend, with the public approving and officials from Parliament and the Church disapproving. Following advice from Edward, Elizabeth forbids a devastated Margaret from marrying Townsend, who then departs for Brussels. The Queen Mother complains about Philip's domineering attitude towards Charles. Lascelles and the Queen Mother suggest that Elizabeth ask Philip to open the Summer Olympics in Melbourne so that he can adjust to life in her shadow. A five-month royal tour is later added to the itinerary, with Elizabeth suggesting he be thankful that everyone is helping him find a public role. Eden replaces Churchill as Prime Minister and becomes trapped in an escalating dispute with Egyptian President Nasser over the rights to the Suez Canal. | ||||||

Release

[edit]The series's first two episodes were released theatrically in the United Kingdom on 1 November 2016.[9] The first season was released on Netflix worldwide in its entirety on 4 November 2016.[10][11] Season one was released on DVD and Blu-ray in the United Kingdom on 16 October 2017 and worldwide on 7 November 2017.[12][13]

Music

[edit]| The Crown: Season One | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Soundtrack album by Hans Zimmer (title theme) and Rupert Gregson-Williams (original score) | ||||

| Released | 4 November 2016 | |||

| Genre | Soundtrack | |||

| Length | 1:06:19 | |||

| Label | Sony Music | |||

| The Crown music chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Hans Zimmer soundtrack chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Rupert Gregson-Williams soundtrack chronology | ||||

| ||||

All music composed by Rupert Gregson-Williams, except where noted:

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Crown Main Title" (composed by Hans Zimmer) | 1:24 |

| 2. | "Duck Shoot" | 4:07 |

| 3. | "Sagana" | 4:32 |

| 4. | "Government" | 4:06 |

| 5. | "The Letter" | 7:56 |

| 6. | "Limerick" | 2:49 |

| 7. | "Edward Returns" | 2:02 |

| 8. | "In This Together" | 5:59 |

| 9. | "Margaret and Townsend" | 3:13 |

| 10. | "The Anointing" | 5:13 |

| 11. | "Someone Remarkable" | 4:15 |

| 12. | "Where Does That Leave Me?" | 1:39 |

| 13. | "Margaret Calls Elizabeth" | 4:01 |

| 14. | "Bit of Fluff" | 2:30 |

| 15. | "Dressing Down" | 3:09 |

| 16. | "Mary is Dead" | 1:45 |

| 17. | "Mary and Edward" | 3:31 |

| 18. | "Chasing Margaret" | 1:37 |

| 19. | "Head of the Family" | 2:41 |

| Total length: | 1:06:19 | |

Reception

[edit]

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported 88% approval for the first season based on 77 reviews, with an average rating of 8.60/10. Its critical consensus reads, "Powerful performances and lavish cinematography make The Crown a top-notch production worthy of its grand subject."[14] On Metacritic, the series holds a score of 81 out of 100, based on 29 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[15]

The Guardian's TV critic Lucy Mangan praised the series and wrote that "Netflix can rest assured that its £100m gamble has paid off. This first series, about good old British phlegm from first to last, is the service's crowning achievement so far."[16] Writing for The Daily Telegraph, Ben Lawrence said, "The Crown is a PR triumph for the Windsors, a compassionate piece of work that humanises them in a way that has never been seen before. It is a portrait of an extraordinary family, an intelligent comment on the effects of the constitution on their personal lives and a fascinating account of postwar Britain all rolled into one."[17] Writing for The Boston Globe, Matthew Gilbert also praised the series saying it "is thoroughly engaging, gorgeously shot, beautifully acted, rich in the historical events of postwar England, and designed with a sharp eye to psychological nuance".[18] Vicki Hyman of The Star-Ledger described it as "sumptuous, stately but never dull".[19] The A.V. Club's Gwen Ihnat said it adds "a cinematic quality to a complex and intricate time for an intimate family. The performers and creators are seemingly up for the task".[20]

The Wall Street Journal critic Dorothy Rabinowitz said, "We're clearly meant to see the duke [of Windsor] as a wastrel with heart. It doesn't quite come off—Mr. Jennings is far too convincing as an empty-hearted scoundrel—but it's a minor flaw in this superbly sustained work."[21] Robert Lloyd writing for the Los Angeles Times said, "As television it's excellent—beautifully mounted, movingly played and only mildly melodramatic."[22] Hank Stuever of The Washington Post also reviewed the series positively: "Pieces of The Crown are more brilliant on their own than they are as a series, taken in as shorter, intently focused films".[23] Neil Genzlinger of The New York Times said, "This is a thoughtful series that lingers over death rather than using it for shock value; one that finds its story lines in small power struggles rather than gruesome palace coups."[24] The Hollywood Reporter's Daniel Fienberg said the first season "remains gripping across the entirety of the 10 episodes made available to critics, finding both emotional heft in Elizabeth's youthful ascension and unexpected suspense in matters of courtly protocol and etiquette".[25] Other publications such as USA Today,[26] Indiewire,[27] The Atlantic,[28] CNN[29] and Variety[30] also reviewed the series positively.

Some were more critical of the show. In a review for Time magazine, Daniel D'Addario wrote that it "will be compared to Downton Abbey, but that .. was able to invent ahistorical or at least unexpected notes. Foy struggles mightily, but she's given little...The Crown's Elizabeth is more than unknowable. She's a bore".[31] Vulture's Matt Zoller Seitz concluded, "The Crown never entirely figures out how to make the political and domestic drama genuinely dramatic, much less bestow complexity on characters outside England's innermost circle."[32] Verne Gay of Newsday said, "Sumptuously produced but glacially told, The Crown is the TV equivalent of a long drive through the English countryside. The scenery keeps changing, but remains the same."[33] Slate magazine's Willa Paskin, commented: "It will scratch your period drama itch—and leave you itchy for action."[34]

Awards

[edit]Lithgow won the 2017 Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series for his performance in the episode "Assassins."[35]

Historical accuracy

[edit]The re-enactment of the removal of King George VI's cancerous lung, originally performed by Sir Clement Price Thomas, was researched and planned by Pankaj Chandak, a specialist in transplant surgery at Guy's Hospital, London. Chandak and his surgical team then became part of the actual scene filmed for the show, with surgeon Nizam Mamode appearing as Price Thomas.[36] The surgical model of King George VI was donated to the Gordon Museum of Pathology in King's College, London for use as a teaching aid.[37]

The show has been interpreted as perpetuating the idea that the Queen and Churchill forced Princess Margaret to give up her plan to marry Peter Townsend and depicted the Queen informing her that, due to the Royal Marriages Act 1772, she would no longer be a member of the family if they married. However, there is clear evidence that, in reality, efforts had been made by the Queen and Anthony Eden in developing a plan that would have allowed Princess Margaret to keep her royal title and her civil list allowance, stay in the country, and continue with her public duties but she would have been required to renounce her rights of succession and those of her children.[38]

Though the show depicted a dispute over Michael Adeane being the natural successor to Tommy Lascelles as the Queen's private secretary, this did not, in reality, happen; Martin Charteris accordingly took the role in 1972.[39][40]

Royal biographer Hugo Vickers denied that Princess Margaret had acted as monarch while the Queen was on tour and claimed that her speech at the ambassador's reception never happened. Charteris was on tour with the Queen and not in London during these events. The Queen Mother bought the Castle of Mey a year earlier than depicted on the show, and often looked after Prince Charles and Princess Anne while the Queen was away.[39][41]

Churchill's wife Clementine is depicted as overseeing the burning of her husband's portrait by artist Graham Sutherland shortly after Churchill's retirement. In reality, the painting was destroyed by the brother of their private secretary, Grace Hamblin, without the involvement of Hamblin herself.[39][42]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Singh, Anita (19 August 2015). "£100m Netflix Series Recreates Royal Wedding". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ Smith, Russ (13 December 2016). "The Crown: What year did Series 1 finish? What will be in season 2?". Daily Express. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ a b c "Trailers for Netflix series 'The Crown,' and 'The Get Down'". Geeks of Doom. 6 January 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ a b Lloyd, Kenji (7 January 2016). "The Crown trailer: First look at Peter Morgan's Netflix drama". Final Reel. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (21 August 2015). "Why Britain's psyche is gripped by a different kind of royal fever". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ a b "The Crown Season Two: Representation vs Reality". Netflix. 11 December 2017. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Lacey, Robert. The Crown: The Inside History. London: Blink Publishing, 2017. 354.

- ^ Gruccio, John (6 January 2016). "The trailer for Netflix's royal drama series, "The Crown"". TMStash. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "The Crown [Season 1, Episodes 1 & 2] (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 25 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ Kickham, Dylan (11 April 2016). "Matt Smith's Netflix drama The Crown gets premiere date". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ "Claire Foy and Matt Smith face the challenges of royal life in new extended trailer for Netflix drama The Crown". Radio Times. 27 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ "The Crown: Season 1 [DVD] [2017]". amazon.co.uk. 16 October 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "The Crown (TV Series)". dvdsreleasedates.com. 7 November 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "The Crown: Season 1 (2016)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ "The Crown:Season 1". Metacritic. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Mangan, Lucy (4 November 2016). "The Crown review – the £100m gamble on the Queen pays off royally". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Lawrence, Ben (2 November 2016). "The Crown, spoiler-free review: Netflix's astonishing £100 million gamble pays off". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Gilbert, Matthew (3 November 2016). "Netflix's 'The Crown' bows to the queen". Boston Globe. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Hyman, Vicki (3 November 2016). "'The Crown' review: 'Downton Abbey' fans, meet your new (and better) obsession". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Ihnat, Gwen (2 November 2016). "The Crown is a visually sumptuous family drama fit for a queen". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Dorothy (3 November 2016). "'The Crown' Review: The Making of Elizabeth II". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Lloyd, Robert (20 September 2016). "Netflix's 'The Crown' is a winning tale of royals and the weight of tradition". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Stuever, Hank (2 November 2016). "Netflix's 'The Crown' is best when viewed like separate little movies". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (2 November 2016). "Review: Netflix Does Queen Elizabeth II in 'The Crown,' No Expense Spared". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Fienberg, Daniel (1 November 2016). "'The Crown': TV Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ Bianco, Robert (4 November 2016). "Review: 'The Crown' is sumptuous miniseries with stellar cast". USA Today. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Travers, Ben (2 November 2016). "'The Crown' Review: Netflix Period Drama Came to Reign in Made-To-Order Emmys Contender". Indiewire. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Sims, David (2 November 2016). "The Crown Is a Sweeping, Sumptuous History Lesson". The Atlantic. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (2 November 2016). "'The Crown' regally explores reign of Queen Elizabeth". CNN. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Ryan, Maureen (2 November 2016). "TV Review: 'The Crown'". Variety. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ D'Addario, Daniel (4 November 2016). "Review: Netflix's The Crown Makes the Most of an Unknowable Queen". Time. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Seitz, Matt Zoller (2 November 2016). "Netflix's The Crown Is Tedious, But Anglophiles Will Like It". New York. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Gay, Verne (4 November 2016). "The Crown Review: Queen Elizabeth Story Falls Flat". Newsday. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Paskin, Willa (3 November 2016). "Netflix's sumptuous $100 million drama about the British monarchy delivers exactly what it promises. That isn't enough". Slate. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Liao, Shannon (17 September 2017). "John Lithgow wins the Emmy for Supporting Actor in a Drama Series". The Verge. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Surgeons replace actors in The Crown's King George VI operation scene". AOL UK. 5 November 2016. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ "Inside the Gordon Museum – King's Alumni Community". alumni.kcl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ Reynolds, Paul (19 November 2016). "Did the Queen stop Princess Margaret marrying Peter Townsend?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Vickers, Hugo (17 November 2019). "How accurate is The Crown? We sort fact from fiction in the royal drama". The Times. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "The Crown: Who was the real Martin Charteris?". Radio Times. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Smith, Reiss (12 December 2016). "The Crown: What castle did the Queen Mother buy in Scotland when she was in mourning?". Daily Express. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "The Crown: What really happened to Graham Sutherland's controversial portrait of Winston Churchill?". RadioTimes. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

External links

[edit]- * The Crown season 1 on Netflix

- The Crown at IMDb