Collecting

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2010) |

| Collecting |

|---|

| Terms |

| Topics |

The hobby of collecting includes seeking, locating, acquiring, organizing, cataloging, displaying, storing, and maintaining items that are of interest to an individual collector. Collections differ in a wide variety of respects, most obviously in the nature and scope of the objects contained, but also in purpose, presentation, and so forth. The range of possible subjects for a collection is practically unlimited, and collectors have realised a vast number of these possibilities in practice, although some are much more popular than others.

In collections of manufactured items, the objects may be antique or simply collectable. Antiques are collectable items at least 100 years old, while other collectables are arbitrarily recent. The word vintage describes relatively old collectables that are not yet antiques.

Collecting is a childhood hobby for some people, but for others, it is a lifelong pursuit or something started in adulthood. Collectors who begin early in life often modify their goals when they get older. Some novice collectors start by purchasing items that appeal to them and then slowly work at learning how to build a collection, while others prefer to develop some background in the field before starting to buy items. The emergence of the internet as a global forum for different collectors has resulted in many isolated enthusiasts finding each other.

Types of collection

[edit]

The most obvious way to categorize collections is by the type of objects collected. Most collections are of manufactured commercial items, but natural objects such as birds' eggs, butterflies, rocks, and seashells can also be the subject of a collection. For some collectors, the criterion for inclusion might not be the type of object but some incidental property such as the identity of its original owner.

Some collectors are generalists with very broad criteria for inclusion, while others focus on a subtopic within their area of interest. Some collectors accumulate arbitrarily many objects that meet the thematic and quality requirements of their collection, others—called completists or completionists—aim to acquire all items in a well-defined set that can in principle be completed, and others seek a limited number of items per category (e.g. one representative item per year of manufacture or place of purchase).[1] Collecting items by country (e.g. one collectible per country) is very common. The monetary value of objects is important to some collectors but irrelevant to others. Some collectors maintain objects in pristine condition, while others use the items they collect.

Value of collected items

[edit]

After a collectable has been purchased, its retail price no longer applies and its value is linked to what is called the secondary market. There is no secondary market for an item unless someone is willing to buy it, and an object's value is whatever the buyer is willing to pay. Depending on age, condition, supply, demand, and other factors, individuals, auctioneers, and secondary retailers may sell a collectable for either more or less than what they originally paid for it. Special or limited edition collectables are created with the goal of increasing demand and value of an item due to its rarity. A price guide is a resource such as a book or website that lists typical selling prices.

Products often become more valuable with age. The term antique generally refers to manufactured items made over 100 years ago,[2] although in some fields, such as antique cars, the time frame is less stringent. For antique furniture, the limit has traditionally been set in the 1830s. Collectors and dealers may use the word vintage to describe older collectables that are too young to be called antiques,[3] including Art Deco and Art Nouveau items, Carnival and Depression glass, etc. Items which were once everyday objects but may now be collectable, as almost all examples produced have been destroyed or discarded, are called ephemera.

Psychological aspects

[edit]Psychological factors can play a role in both the motivation for keeping a collection and the impact it has on the collector's life. These factors can be positive or negative.[4]

The hobby of collecting often goes hand-in-hand with an interest in the objects collected and what they represent, for example collecting postcards may reflect an interest in different places and cultures. For this reason, collecting can have educational benefits, and some collectors even become experts in their field.

Maintaining a collection can be a relaxing activity that counteracts the stress of life, while providing a purposeful pursuit which prevents boredom. The hobby can lead to social connections between people with similar interests and the development of new friendships. It has also been shown to be particularly common among academics.[citation needed]

Collecting for most people is a choice, but for some it can be a compulsion, sharing characteristics with obsessive hoarding. When collecting is passed between generations, it might sometimes be that children have inherited symptoms of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Collecting can sometimes reflect a fear of scarcity, or of discarding something and then later regretting it.

Carl Jung speculated that the widespread appeal of collecting is connected to the hunting and gathering that was once necessary for human survival.[5] Collecting is also associated with memory by association and the need for the human brain to catalogue and organise information and give meaning to ones actions.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

Collecting is a practice with a very old cultural history. In Mesopotamia, collecting practices have been noted among royalty and elites as far back as the 3rd millennium BCE.[6] The Egyptian Ptolemaic dynasty collected books from all over the known world at the Library of Alexandria. The Medici family, in Renaissance Florence, made the first effort to collect art by private patronage, this way artists could be free for the first time from the money given by the Church and Kings; this citizenship tradition continues today with the work of private art collectors. Many of the world's popular museums—from the Metropolitan in New York City to the Thyssen in Madrid or the Franz Mayer in Mexico City—have collections formed by the collectors that donated them to be seen by the general public.

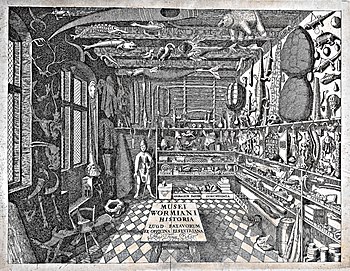

The collecting hobby is a modern descendant of the "cabinet of curiosities" which was common among scholars with the means and opportunities to acquire unusual items from the 16th century onwards. Planned collecting of ephemeral publications goes back at least to George Thomason in the reign of Charles I and Samuel Pepys in that of Charles II. Collecting engravings and other prints by those whose means did not allow them to buy original works of art also goes back many centuries. The progress in 18th-century Paris of collecting both works of art and of curiosité, dimly echoed in the English curios, and the origins in Paris, Amsterdam and London of the modern art market have been increasingly well documented and studied since the mid-19th century.[7]

The involvement of larger numbers of people in collecting activities came with the prosperity and increased leisure for some in the later 19th century in industrial countries. That was when collecting such items as antique china, furniture and decorative items from oriental countries became established. The first price guide was the Stanley Gibbons catalogue issued in November 1865.

The history of collecting is chronicled in the book Lock, Stock, and Barrel: The story of collecting. This well-researched book on collecting, written by Elizabeth and Douglas Rigby, was published by J. B. Lippincott & Co., a major publisher in Philadelphia.[8] “An important book as well as a delightful one. I recommend it urgently as the best all around volume in its field,” wrote Vincent Starrett of the Chicago Tribune in a review of the book.[9] In addition to being reviewed by newspapers, magazines, and journals -- such as The Chicago Tribune, The New York Times, The Saturday Review, New York History, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History, and The American Scholar -- the book also has been cited in academic studies on collecting.[10][11][12][13]

Notable collectors

[edit]- Alfred Chester Beatty — various collections

- Barry Halper — baseball memorabilia

- Bella Clara Landauer — various, primarily ephemera

- Charles Wesley Powell — orchids

- Christopher Ross, Imperial militaria

- Demi Moore — dolls

- Donald Kaufman — antique toys

- Forrest J Ackerman — books and movie memorabilia

- Geddy Lee — bass guitars

- George Gustav Heye — Native American artifacts

- George Weare Braikenridge — primarily art of Bristol

- Hans Sachs — posters

- Hans Sloane — natural history

- Harvey H. Nininger — meteorites

- Henry Wellcome — medical objects

- James Allen — antiques and photographs

- Joaquín Rubio y Muñoz — antique coins

- J. P. Morgan — various, primarily gems

- Kenneth W. Rendell — historical documents, primarily World War II

- King George V — stamps

- Magnus Walker — Porsches

- Margaret Bentinck, Duchess of Portland — primarily natural history

- Martin Hill — cameras

- Philipp von Ferrary — stamps and coins

- Raleigh DeGeer Amyx — historical memorabilia

- Sam Wagstaff — various collections

- Tim Rowett — children's toys and novelties

- Tom Hanks — typewriters

- William Dixson — primarily Australiana

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Blom, Philipp (2005) To Have and To Hold: an intimate History of collectors and collecting. ISBN 1-58567-377-3

- Castruccio, Enrico (2008) "I Collezionisti: usi, costumi, emozioni". Cremona: Persico Edizioni ISBN 88-87207-59-3

- Chaney, Edward, ed. (2003) The Evolution of English Collecting. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Schulz, Charles M. (1984) Charlie Brown's Super Book of Things to Do and Collect: based on the Charles M. Schulz characters. New York: Random House, 1984, paperback, ISBN 0-394-83165-9, (hardcover in library binding ISBN 0-394-93165-3)

- Redman, Samuel J. (2016) Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

- Rigby, Douglas and Rigby, Elizabeth (1944) Lock, Stock and Barrel: The Story of Collecting. Philadelphia: J B Lippincott. 9781299010123, 1299010121

- Shamash, Jack, (2013) George V's Obsession – a King and His Stamps

- Shamash, Jack (2014) The Sociology of Collecting

- Thomason, Alison Karmel (2005) Luxury and Legitimation: Royal Collecting in Ancient Mesopotamia. Hampshire, U.K.: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- van der Grijp, Paul (2006) Passion and Profit: Towards an Anthropology of Collecting. Berlin: LIT Verlag. ISBN 3-8258-9258-1

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ For example, book collector Rush Hawkins (1831–1920) sought the first and second books from every European printer before 1501, while illuminated manuscript collector Henry Yates Thompson (1838–1928) maintained a collection of exactly 100 items, selling his least preferable items to make room for new ones.

- ^ For example, U.S. Customs and Border Protection requires that an antique "must be over 100 years of age at the time of importation". U.S. Customs and Border Protection, CBP Information Center (27 September 2019). "Duty on personal and commercial imports of antiques, artwork". Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ For example, the arts and crafts sales website Etsy requires "vintage" items sold on their platform to be "at least 20 years old". "Vintage Items on Etsy". 18 October 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mueller, Shirley M. (2019). Inside the Head of a Collector: Neuropsychological Forces at Play. Seattle. ISBN 978-0-9996522-7-5. OCLC 1083575943.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Schwager, David (17 January 2017). "Why Do We Want This Stuff? Eight Views on the Psychology of Collecting". CoinWeek. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Thomason, Alison Karmel Thomason (2005). Luxury and Legitimation: Royal Collecting in Ancient Mesopotamia. Hampshire, U.K.: Ashgate Publishing Limited. ISBN 0754602389.

- ^ Chronologically some essential works are C. Blanc, Le trésor de la curiosité (1857–58), E. Bonnaffé, Les collectionneurs de l'ancienne France (1873), l. Courajod, La livre-journal de Lazare Duvaux (1873), L. Clément de Ris, Les amateurs d'autrefois (1877), A. Maze-Sencier, Le livre des collectionneurs (1893), G. Reitlinger The Economics of Taste (1961), G. Glorieux's monograph, À l'Enseigne de Gersaint (2002).

- ^ "Habits of the Magpie; LOCK, STOCK AND BARREL: The Story of Collecting". The New York Times. 14 December 1944. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Vincent Starret Papers". Modern Manuscripts & Archives at the Newberry. The Newberry Library. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Storm, Colton (1946). "Review of Lock, Stock and Barrel. The Story of Collecting". No. 70 (3): 336–337. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. JSTOR 20087847. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Dictators and the Gentle Art of Collecting"". No. 11 (2): 168–180. The American Scholar. 1942. JSTOR 41203580. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Schuchardt Navratil, Emily (February 2015). "Native American Chic: The Marketing Of Native Americans In New York Between The World Wars". CUNY Academic Works. City University of New York. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ MacFarlane, Janet (1946). ""Books About Antiques". No. 26 (2): 224–225. New York History. JSTOR 23149570. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

External links

[edit]- Journal of the History of Collections (archived 12 April 2009)

- Center for the History of Collecting at the Frick Collection (Art collecting) (archived 6 February 2009)

- "Amass Appeal" Essay by Richard Rubin, AARP Magazine, March/April 2008 (archived 7 September 2012).

- Mueller, Shirley M. (2019). Inside the Head of a Collector : Neuropsychological Forces at Play. Seattle. ISBN 978-0-9996522-7-5. OCLC 1083575943.