Conservation and restoration of ancient Greek pottery

The conservation and restoration of ancient Greek pottery is a sub-section of the broader topic of conservation and restoration of ceramic objects. Ancient Greek pottery is one of the most commonly found types of artifacts from the ancient Greek world. The information learned from vase paintings forms the foundation of modern knowledge of ancient Greek art and culture. Most ancient Greek pottery is terracotta, a type of earthenware ceramic, dating from the 11th century BCE through the 1st century CE. The objects are usually excavated from archaeological sites in broken pieces, or shards, and then reassembled. Some have been discovered intact in tombs. Professional conservator-restorers, often in collaboration with curators and conservation scientists, undertake the conservation-restoration of ancient Greek pottery.

History of conservation and restoration approaches

[edit]Ancient

[edit]Ancient repairs were made to damaged pottery using metal pins or staples, which could be made of copper, lead, or bronze.[1] Animal or vegetable-based adhesives may have also been used. Fragments from other vessels were sometimes used to replace damaged or missing sections of an object.[2] The decorative elements on the replacement pieces may or may not have matched the rest of the vase.

18th to early 20th century

[edit]Restoration methods used during the 18th through early 20th century generally attempted to restore vessels to a near-pristine state and hide any evidence of past damage.[1] Archaeological discoveries and a surge in the popularity of ancient Greek art in the 18th and 19th centuries created a high demand for objects and artifacts. The customary restoration method started with reassembling vessel fragments. Missing fragments were replaced with new glazed and fired pieces of pottery and gaps were filled in with plaster. The surface was then painted, sometimes extensively.[1] Materials used included shellac, protein glues, oil paints, gypsum, plaster of Paris, barium sulfate, calcite, clay, kaolin, and water glass (calcium silicate).[3] In some cases, decorative imagery was censored and painted over, in order to appeal to the tastes of contemporary society and potential collectors.[2]

Modern

[edit]The modern approach to conservation generally involves using non-destructive methods to evaluate objects and restoration techniques which emphasize the difference between areas of modern repair and ancient craftsmanship. Reversible adhesives, paint, and other materials are used in restorations.[4] Conservation departments at museums such as the Getty Villa approach conservation of ancient pottery with the goal to "visually integrate filled areas and make them less obtrusive while still distinguishing them from the original ceramic and preserving an object's history."[2]

Materials

[edit]Most ancient Greek pottery is terracotta, a type of earthenware fired clay ceramic. The composition of minerals, metal, organic and other inorganic materials in the clay varies depending on its source. These variations affect the color of the clay before and after firing. Iron is the most common material found in clay, and can add red, grey, or buff coloring to the object.[5] Pottery can be coarse wares, which are undecorated or only minimally decorated utilitarian vessels, or fine wares, which are decorated, finely potted, and used for a variety of purposes, including ceremonial use.

Vase paintings were primarily created using slip, a thin, transparent layer of clay which turned color after firing. Other materials used in vase paintings include added pigment, added clay to create a relief on the surface, or dilute gloss that added color after firing.[6] Unevenly applied gloss or misfiring also created variations in color or surface texture. Gilding was also sometimes added after firing.

Agents of deterioration

[edit]Ceramics, and ancient ceramics in particular, can suffer a variety of types of damage. Most agents of deterioration are due to environment and are inherent to the materials; however, the most common damage is caused by human action.

Physical damage

[edit]Breaks, losses, or abrasions can be caused by improper handling, impact (dropping), or excavation. Ceramics are strong in compression, but weak under tension, meaning they are fragile and susceptible to mechanical shock.[7]

Soluble salts

[edit]If a piece of pottery has been buried in salty or alkaline soil or submersed in seawater, the clay may have soaked up soluble salts, such as sulphite, nitrates, or chlorides. Changes in relative humidity can cause the salts to react and dissolve (in high humidity) or recrystallize (in low humidity).[5] These reactions can cause pottery to suffer surface losses or delamination.[3]

Previous restorations

[edit]Previous restorations can cause unintended damage over time. Metal pins or staples can corrode and deteriorate. Plaster repairs may become unstable. In-painting may fade or discolor. Intentional over-painting from past conservation efforts is another form of damage. Scenes were sometimes altered in order to appeal to current tastes. A common example is a fig leaf being painted over a nude figure. Overly aggressive cleaning with acid can also cause damage. Acid cleaning is meant to remove insoluble salts and minerals from the surface of archaeological ceramics. Pottery that has been improperly cleaned and damaged by acid may have pitted, cracked, powdery, or flaking surfaces.[8]

Preventive conservation

[edit]Preventive conservation measures can help slow further deterioration or damage.

Handling

[edit]As with any fragile ceramic object, proper handling techniques will help prevent accidental damage. Objects should be handled as little as possible. When handling is necessary, objects should be held at their strongest points only. Pressure on the weakest points, such as handles, necks, or areas with existing damage, should be avoided. Objects should be handled with clean, dry hands, or with nitrile gloves. Cotton gloves are not recommended, because the fabric prevents a stable grip and threads can snag on rough surfaces. Objects on display in museums are secured with mounts or protected by cases to prevent unwanted or accidental contact. Vessels may be displayed upright or at an angle, depending on the decorative elements on display. Any mounts should keep the object stable without putting pressure on any fragile areas.

Environmental conditions

[edit]Despite having been dried and fired, pottery clay is still a porous material which will react to changes in environmental conditions. Avoiding extreme changes in temperature can help maintain the condition of ancient Greek pottery. As discussed above in the section on damage from soluble salts, preventing extreme fluctuations in relative humidity can also help prevent further deterioration. Objects should be protected from water and dirt.

Examination

[edit]The following techniques are used by conservators to evaluate the condition of ancient Greek pottery and determine appropriate treatment. Examination is the first step in the conservation process.

Visual inspection

[edit]Conservators begin the evaluation of an object with careful visual inspection to identify areas of weakness, loss, delamination, discoloration, or old repairs. Further examination with a low power microscope can help conservators identify materials and technical features, such as pigment, gilding, or added clay.[9]

Ultraviolet (UV) visible fluorescence

[edit]When exposed to invisible UV light, many types of materials will display certain colors of visible light. This can enable conservators to identify areas of different media throughout the object.[9]

X-radiography

[edit]X-rays can reveal breaks, internal features, or hidden ancient repairs, such as pins.[9] Another type of X-ray, called X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy, can reveal the elemental and chemical composition of a material. X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy can reveal the iron oxidation states in pottery (the factor that determines black and red color) and X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analyses can provide information on the molecular structure of iron minerals.[10]

Conservation treatment

[edit]After evaluation is completed, conservator-restorers can determine the most appropriate form of treatment. Treatments can range from non-invasive techniques, such as cleaning, to more invasive conservation, such as disassembly, reconstruction, and restoration.

Cleaning

[edit]Basic mechanical cleaning can remove dirt, dust, and grime. Cleaning solvents and water can also be used to remove dirt, varnish, wax, in-painting, or adhesives. Acids should be used with caution. Desalination is a cleaning method that removes as much soluble salt from the porous fired clay as possible. Fragments are soaked in highly purified water for multiple days. The water is changed regularly until salt levels are reduced.[11]

Disassembly

[edit]For vessels that have been previously conserved and reassembled, shards may need to be disassembled in order to remove old restoration materials and complete conservation. Adhesives and fill are systematically removed, revealing the original pottery and allowing the vessel to be deconstructed.

Reconstruction and restoration

[edit]Separated shards are carefully reassembled. Conservators use identifying clues, such as shape, texture, and decorative pattern or painted scenes, to piece together fragments. Missing shards can be recreated out of plaster and replaced. In-painting is used to disguise areas of repair. In modern conservation treatment, the media used by conservators is reversible and can be distinguished easily from ancient material. Different conservators, or conservation departments, may have different policies regarding in-painting. Some conservators leave replacement fragments completely undecorated in order to easily distinguish them as modern additions. Some conservators paint silhouettes of missing figures, using existing fragments, scene narrative, and other extant vases as examples. This approach helps show the narrative of the painted scene, while still distinguishing the modern restoration from the original fragments. Some conservators use more extensive in-painting to recreate missing decoration.

Notable examples

[edit]The Affecter Amphora, in the collection of the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, Maryland, is a case study for the history of conservation of Greek vases. The black figured Attic (meaning from Athens region) vessel was created around 540 BCE by a well-documented vase painter known as the Affecter Painter. Treatment of the vase in the 1980s provided the conservation field with significant insight into the history of the restoration of Greek vases. Conservators discovered that the amphora had been broken and repaired in antiquity. Samples of burial dirt found within holes in the vase proved that the repairs were made prior to the vase being used in an ancient funeral. Conservators also discovered that the vase was restored in the late 19th century with materials and methods typical of the time period. Plaster, replacement pieces of terracotta, and extensive overpainting had been used in the restoration. Overpainting disguised repairs and also altered the appearance of nude satyrs on the decorative panels. The 1980s conservation revealed the original work of the Affecter Painter and restored the vase to a stable condition.[12]

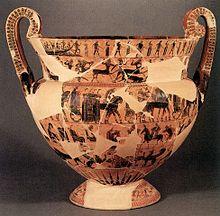

The Francois Vase, in the collection of the National Archaeological Museum in Florence, Italy, is a large Attic volute krater, which is both a superb example of black-figure pottery from c. 570–560 BCE, as well as an example of extensive conservation work. The vase was discovered in a tomb in 1844. In the year 1900, a member of the museum staff smashed the display case and the vase shattered into over 600 pieces. It was restored by 1902, and then restored again in 1973, with previously missing pieces.

See also

[edit]- South Italian ancient Greek pottery

- Disjecta membra

- Pottery

- Typology of Greek vase shapes

- Ancient Greek crafts

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Snow, Carol (1986). "The Affecter Amphora: A Case Study in the History of Greek Vase Restoration." The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, 44, 4.

- ^ a b c Fragment to Vase: Approaches to Ceramic Conservation http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/fragment_to_vase/

- ^ a b Conservation Project: Greek Vases. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston http://www.mfa.org/collections/conservation/feature_greekvases

- ^ Snow, Carol (1986). "The Affecter Amphora: A Case Study in the History of Greek Vase Restoration." The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, 44, 6.

- ^ a b Care of Ceramics and Glass - Canadian Conservation Institute http://canada.pch.gc.ca/eng/1439925170205 Archived 2017-04-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Oakley, John H. The Greek Vase: Art of the Storyteller (London: British Museum, 2013), 16.

- ^ Buys, Susan and Victoria Oakley, Conservation and Restoration of Ceramics (Routledge, 2014), 18.

- ^ National Park Service. "Long-term Effects of acid-cleaning on archaeological ceramics," Conserve-O-Gram (September 1999) https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/06-06.pdf

- ^ a b c Fragment to Vase: Examination Methods http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/fragment_to_vase/examination_methods.html

- ^ Abraham, Melissa. "Deciphering the Elements of Iconic Pottery," National Science Foundation (March 28, 2011) https://www.nsf.gov/mobile/discoveries/disc_summ.jsp?cntn_id=119082&org=NSF

- ^ Usui, Emiko and Julia Gaviria, Eds., Conservation and Care of Museum Collections (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2011), 152.

- ^ Snow, Carol (1986). "The Affecter Amphora: A Case Study in the History of Greek Vase Restoration." The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, 44.

External links

[edit]- The restoration of Greek pottery (it. "Il restauro dei Vasi Greci") https://www.academia.edu/3524033/Il_restauro_dei_vasi_greci

- The Art of Mending Ceramics Disasters. Conservation Lab https://creators.vice.com/en_us/article/mending-ceramics-conservation-lab

- Athenian Pottery Project http://www.getty.edu/conservation/our_projects/science/athenian/

- A Closer Look at Greek Vases. Kemper Art Museum https://mlkemperartmuseum.wordpress.com/2014/12/16/a-closer-look-at-ancient-greek-vases/

- Recreating Ancient Greek Ceramics http://archaeologicalmuseum.jhu.edu/the-collection/object-stories/recreating-ancient-greek-ceramics/

- X-rays reveal artistry in an ancient vase http://news.stanford.edu/features/2016/slac/art.html