Presidency of Jomo Kenyatta

| |

| Presidency of Jomo Kenyatta 12 December 1964 – 22 August 1978 | |

Jomo Kenyatta | |

| Party | KANU |

| Seat | State House |

|

| |

| History of Kenya |

|---|

|

|

|

The presidency of Jomo Kenyatta began on 12 December 1964, when Jomo Kenyatta was named as the 1st president of Kenya, and ended on 22 August 1978 upon his death. Jomo Kenyatta, a KANU member, took office following the formation of the republic of Kenya after independence following his efforts during the fight for Independence. Four years later, in the 1969 elections, he was the sole candidate and was elected unopposed for a second term in office. In 1974, he was re-elected for a third term. Although the post of President of Kenya was due to be elected at the same time as the National Assembly, Jomo Kenyatta was the sole candidate and was automatically elected without a vote being held. He died on 22 August 1978 while still in office and was succeeded by Daniel arap Moi.

1964 presidential election

[edit]In December 1964, Kenya was officially proclaimed a republic. Kenyatta became its executive president, combining the roles of head of state and head of government. Although the position for presidency was open for election, Kenyatta was the sole unopposed candidate and was thus proclaimed president without any voting for that position. The bid to have Kenyatta named the unopposed president followed a systematic elimination of opposition candidates during his time as prime minister of Kenya. The May 1963 general election pitted Kenyatta's KANU against KADU, the Akamba People's Party, and various independent candidates. KANU was victorious with 83 seats out of 124 in the House of Representatives; a KANU majority government replaced the pre-existing coalition. On 1 June 1963, Kenyatta was sworn in as prime minister of the autonomous Kenyan government.

Immediately following his swearing in as president, Kenyatta faced domestic opposition and in January 1964, sections of the army launched a mutiny in Nairobi, with Kenyatta calling on the British Army to put down the rebellion. Similar armed uprisings had taken place that month in neighboring Uganda and Tanganyika. Kenyatta was outraged and shaken by the mutiny. He publicly rebuked the mutineers, emphasizing the need for law and order in Kenya. To prevent further military unrest, he brought in a review of the salaries of the army, police, and prison staff, leading to pay rises. Kenyatta also wanted to contain parliamentary opposition and at Kenyatta's prompting, in November 1964 KADU officially dissolved and its representatives joined KANU. Two of the senior members of KADU, Ronald Ngala and Daniel arap Moi, subsequently became some of Kenyatta's most loyal supporters. Kenya therefore became a de facto one-party state. As a result, he had succeeded in stifling any possible opposition and scared away any candidates who might have thought of vying against him.[1]

Election process and results

[edit]Since was a de facto one-party state with the Kenya African National Union being the sole party to participate in the election. 740 KANU candidates stood for the 158 National Assembly seats, with 88 incumbents (including four ministers) defeated. Voter turnout was 56.5%. Out of 4.6 million registered voters at the time, a total of 2.6 million votes were cast and KANU got 100% of the votes. Following the election, a further 12 members were appointed by President Kenyatta.[2]

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenya African National Union | 2,627,308 | 100 | 158 | 0 |

| Appointed members | − | − | 12 | − |

| Total | 2,627,308 | 100 | 170 | 0 |

| Registered voters/turnout | 4,654,465 | − | − | |

| Source: Nohlen et al. | ||||

Inauguration and cabinet

[edit]

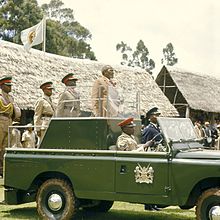

The inauguration of Jomo Kenyatta as president took place on 12 December 1964. It was staged to coincide exactly with the year Kenya attained independence in 1963.[3] This led to the dedication of 12 December as a national holiday named Jamuhuri Day.

Jomo Kenyatta did not form a new cabinet when he became president. The first cabinet formed by Jomo Kenyatta was in 1963 and it continued in force for the entire term. Notably, Kenyatta was prime minister when he formed his first cabinet and his position changed to president after his swearing in. Another major change was the appointment of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, who was previously the Home affairs Minister, as his vice president. The rest of the cabinet was constituted as follows:

| Cabinet position | Cabinet member | |

|---|---|---|

| President | Jomo Kenyatta | |

| Vice president | Jaramogi Oginga Odinga | |

| Justice and Constitutional Affairs | Thomas J. Mboya | |

| Finance and Economic Planning | James S. Gichuru | |

| Minister of State in the Prime Minister's Office | Joseph A. Murumbi | |

| Minister of State for Pan African Affairs | Mbiyu Koinange | |

| Health and Housing | Dr. Njoroge Mungai | |

| Education | Joseph D. Otiende | |

| Agriculture | Bruce McKenzie | |

| Local Government | Samuel O. Ayodo | |

| Commerce and Industry | Julius G. Kiano | |

| Works, Communication and Power | Dawson Mwanyumba | |

| Labour and Social Services | Eluid Mwendwa | |

| Natural Resources | Laurence Sagini | |

| Information, Broadcasting and Tourism | Ramogi Achieng Oneko | |

| Lands and Settlement | Jackson H. Angaine |

Legislation and decisions office

[edit]Immediately he became president, Kenyatta started implementing constitutional amendments to increase the president's power.[5] For instance, a May 1966 amendment gave the president the ability to order the detention of individuals without trial if he thought the security of the state was threatened.[6] Seeking the support of Kenya's second largest ethnic group, the Luo, Kenyatta appointed the Luo Oginga Odinga as his vice president.[7] However, the Kikuyu—who made up around 20 percent of population—still held most of the country's important government and administrative positions.[8] This contributed to a perception among many Kenyans that independence had simply seen the dominance of a British elite replaced by the dominance of a Kikuyu elite.[9]

Kenyatta's calls to forgive and forget the past were a keystone of his government.[10] He preserved various elements of the old colonial order, particularly on issues of law and order.[11] The police and military structures were left largely intact.[11] White Kenyans were left in senior positions within the judiciary, civil service, and parliament,[12] with the white Kenyans Bruce Mackenzie and Humphrey Slade being among Kenyatta's top officials.[13] Kenyatta's government nevertheless rejected the idea that the European and Asian minorities could be permitted dual citizenship, expecting these communities to offer total loyalty to the independent Kenyan state.[14] His administration pressured whites-only social clubs to adopt multi-racial entry policies,[15] and in 1964 schools formerly reserved for European pupils were opened to Africans and Asians.[15]

Kenyatta's government believed it necessary to cultivate a united Kenyan national culture.[16] To this end, it made efforts to assert the dignity of indigenous African cultures which missionaries and colonial authorities had belittled as "primitive".[17] An East African Literature Bureau was created to publish the work of indigenous writers.[18] The Kenya Cultural Centre supported indigenous art and music, with hundreds of traditional music and dance groups being formed; Kenyatta personally insisted that such performances were held at all national celebrations.[19] Support was given to the preservation of historic and cultural monuments, while street names referencing colonial figures were renamed and symbols of colonialism—like the statue of British settler Hugh Cholmondeley, 3rd Baron Delamere in Nairobi city centre—were removed.[18] The government encouraged the use of Swahili as a national language, although English remained the main medium for parliamentary debates and the language of instruction in schools and universities.[17] The historian Robert M. Maxon nevertheless suggested that "no national culture emerged during the Kenyatta era", with most artistic and cultural expressions reflecting particular ethnic groups rather than a broader sense of Kenyanness, while Western culture remained heavily influential over the country's elites.[20]

Economic policy

[edit]Independent Kenya had an economy heavily molded by colonial rule; agriculture dominated while industry was limited, and there was a heavy reliance on exporting primary goods while importing capital and manufactured goods.[21] Under Kenyatta, the structure of this economy did not fundamentally change, remaining externally oriented and dominated by multinational corporations and foreign capital.[22] Kenyatta's economic policy was capitalist and entrepreneurial,[23] with no serious socialist policies being pursued;[24] its focus was on achieving economic growth as opposed to equitable redistribution.[25] The government passed laws to encourage foreign investment, recognizing that Kenya needed foreign-trained specialists in scientific and technical fields to aid its economic development.[26] Under Kenyatta, Western companies regarded Kenya as a safe and profitable place for investment;[27] between 1964 and 1970, large-scale foreign investment and industry in Kenya nearly doubled.[25]

In contrast to his economic policies, Kenyatta publicly claimed he would create a democratic socialist state with an equitable distribution of economic and social development.[28] In 1965, when Thomas Mboya was minister for economic planning and development, the government issued a Sessional Paper titled "African Socialism and its Application to Planning in Kenya", in which it officially declared its commitment to what it called an "African socialist" economic model.[29] The session proposed a mixed economy with an important role for private capital,[30] with Kenyatta's government specifying that it would only consider nationalization in instances where national security was at risk.[31] Left-wing critics highlighted that the image of "African socialism" portrayed in the document provided for no major shift away from the colonial economy.[32]

Kenya's agricultural and industrial sectors were dominated by Europeans and its commerce and trade by Asians; one of Kenyatta's most pressing issues was to bring the economy under indigenous control.[25] There was growing black resentment towards the Asian domination of the small business sector,[33] with Kenyatta's government putting pressure on Asian-owned businesses, intending to replace them with African-owned counterparts.[34] The 1965 session paper promised an "Africanization" of the Kenyan economy,[35] with the government increasingly pushing for "black capitalism".[34] The government established the Industrial and Commercial Development Corporation to provide loans for black-owned businesses,[34] and secured a 51% share in the Kenya National Assurance Company.[36] In 1965, the government established the Kenya National Trading Corporation to ensure indigenous control over the trade in essential commodities,[37] while the Trade Licensing Act of 1967 prohibited non-citizens from involvement in the rice, sugar, and maize trade.[38] During the 1970s, this expanded to cover the trade in soap, cement, and textiles.[37] Many Asians who had retained British citizenship were affected by these measures.[39] Between late 1967 and early 1968, growing numbers of Kenyan Asians migrated to Britain;[40] in February 1968 large numbers migrated quickly before a legal change revoked their right to do so.[41] Kenyatta was not sympathetic to those leaving: "Kenya's identity as an African country is not going to be altered by the whims and malaises of groups of uncommitted individuals."[41]

Under Kenyatta, corruption became widespread throughout the government, civil service, and business community.[42] Kenyatta and his family were tied up with this corruption as they enriched themselves through the mass purchase of property after 1963.[43] Their acquisitions in the Central, Rift Valley, and Coast Provinces aroused great anger among landless Kenyans.[44] His family used his presidential position to circumvent legal or administrative obstacles to acquiring property.[45] The Kenyatta family also heavily invested in the coastal hotel business, with Kenyatta personally owning the Leonard Beach Hotel.[46] Other businesses they were involved with included ruby mining in Tsavo National Park, the casino business, the charcoal trade—which was causing significant deforestation—and the ivory trade.[47] The Kenyan press, which was largely loyal to Kenyatta, did not delve into this issue;[48] it was only after his death that publications appeared revealing the scale of his personal enrichment.[49] Kenyan corruption and Kenyatta's role in it was better known in Britain, although many of his British friends—including McDonald and Brockway—chose to believe Kenyatta was not personally involved.[50]

Land, healthcare, and education reform

[edit]

The question of land ownership had deep emotional resonance in Kenya, having been a major grievance against the British colonialists.[51] As part of the Lancaster House negotiations, Britain's government agreed to provide Kenya with £27 million with which to buy out white farmers and redistribute their land among the indigenous population.[52] To ease this transition, Kenyatta made McKenzie, a white farmer, the Minister of Agriculture and Land.[52] Kenyatta's government encouraged the establishment of private land-buying companies that were often headed by prominent politicians.[53] The government sold or leased lands in the former White Highlands to these companies, which in turn subdivided them among individual shareholders.[53] In this way, the land redistribution programs favored the ruling party's chief constituency.[54] Kenyatta himself expanded the land that he owned around Gatundu.[9] Kenyans who made claims to land on the basis of ancestral ownership often found the land given to other people, including Kenyans from different parts of the country.[54] Voices began to condemn the redistribution; in 1969, the MP Jean-Marie Seroney censured the sale of historically Nandi lands in the Rift to non-Nandi, describing the settlement schemes as "Kenyatta's colonization of the rift".[55]

In part fuelled by high rural unemployment, Kenya witnessed growing rural-to-urban migration under Kenyatta's government.[56] This exacerbated urban unemployment and housing shortages, with squatter settlements and slums growing up and urban crime rates rising.[57] Kenyatta was concerned by this, and promoted the reversal of this rural-to-urban migration, but in this was unsuccessful.[58] Kenyatta's government was eager to control the country's trade unions, fearing their ability to disrupt the economy.[36] To this end it emphasized various social welfare schemes over traditional industrial institutions,[36] and in 1965 transformed the Kenya Federation of Labour into the Central Organization of Trade (COT), a body which came under strong government influence.[59] No strikes could be legally carried out in Kenya without COT's permission.[60] There were also measures to the African civil service, which by mid-1967 had become 91% African.[61] During the 1960s and 1970s the public sector grew faster than the private sector.[62] The growth in the public sector contributed to the significant expansion of the indigenous middle class in Kenyatta's Kenya.[63]

The government oversaw a massive expansion in education facilities.[64] In June 1963, Kenyatta ordered the Ominda Commission to determine a framework for meeting Kenya's educational needs, with their report being released eight months later.[65] The report set out the long-term goal of universal free primary education in Kenya but also argued that the government's emphasis should be on secondary and higher education to facilitate the training of indigenous African personnel to take over the civil service and other jobs requiring such an education.[66] Between 1964 and 1966, the number of primary schools in Kenya grew by 11.6%, and the number of secondary schools by 80%.[66] By the time of Kenyatta's death, Kenya's first universities—the University of Nairobi and Kenyatta University—had been established.[67] Although Kenyatta died without having attained the goal of free, universal primary education in Kenya, the country had made significant advances in that direction, with 85% of Kenyan children in primary education, and within a decade of independence had trained sufficient numbers of indigenous Africans to take over the civil service.[68]

Another priority for Kenyatta's government was improving access to healthcare services.[69] It stated that its long-term goal was to establish a system of free, universal medical care.[70] In the short-term, its emphasis was on increasing the overall number of doctors and registered nurses while decreasing the number of expatriates in those positions.[69] In 1965, the government introduced free medical services for out-patients and children.[70] By Kenyatta's death, the majority of Kenyans had access to significantly better healthcare than they had had in the colonial period.[70] Prior to independence, the average life expectancy in Kenya was 45, but by the end of the 1970s it was 55, the second highest in Sub-Saharan Africa.[71] This improved medical care had resulted in declining mortality rates while birth rates remained high, resulting in a rapidly growing population; from 1962 to 1979, Kenya's population grew by just under 4% a year, the highest rate in the world at the time.[72] This put a severe strain on social services, with Kenyatta's government promoting family planning projects to stem the birth-rate, although these had little success.[73]

Foreign policy

[edit]

In part due to his advanced years, Kenyatta rarely travelled outside of Eastern Africa.[74] Under Kenyatta, Kenya was largely un-involved in the affairs of other states, including those in the East African Community.[75] Despite his reservations about any immediate East African Federation, in June 1967 Kenyatta signed the Treaty for East African Co-operation.[76] In December he attended a meeting with Tanzanian and Ugandan representatives to form the East African Economic Community, reflecting Kenyatta's cautious approach toward regional integration.[76] He also took on a mediating role during the Congo Crisis, heading the Organisation of African Unity's Conciliation Commission on the Congo.[77]

Facing the pressures of the Cold War,[78] Kenyatta officially pursued a policy of "positive non-alignment".[79] In reality, his foreign policy was pro-Western and in particular pro-British.[80] Kenya became a member of the British Commonwealth,[81] using this as a vehicle to put pressure on the white-minority apartheid regimes in South Africa and Rhodesia.[82] Britain remained one of Kenya's foremost sources of foreign trade; British aid to Kenya was among the highest in Africa.[79] In 1964, Kenya and the UK signed a Memorandum of Understanding, one of only two military alliances Kenyatta's government made;[79] the British Special Air Service trained Kenyatta's own bodyguards.[83] Various commentators argued that Britain's relationship with Kenyatta's Kenya was a neo-colonial one, with the British having exchanged their position of political power for one of influence.[84] The historian Poppy Cullen nevertheless noted that there was no "dictatorial neo-colonial control" in Kenyatta's Kenya.[79]

Although many white Kenyans accepted Kenyatta's rule, he remained opposed by white far right activists; while in London at the July 1964 Commonwealth Conference, he was assaulted by Martin Webster, a British neo-Nazi.[85] Kenyatta's relationship with the United States was also warm; the United States Agency for International Development played a key role in helping respond to a maize shortage in Kambaland in 1965.[86] Kenyatta also maintained a warm relationship with Israel, including when other East African nations endorsed Arab hostility to the state;[87] he for instance permitted Israeli jets to refuel in Kenya on their way back from the Entebbe raid.[88] In turn, in 1976 the Israelis warned of a plot by the Palestinian Liberation Army to assassinate him, a threat he took seriously.[89]

Kenyatta and his government were anti-communist,[90] and in June 1965 he warned that "it is naive to think that there is no danger of imperialism from the East. In world power politics the East has as much designs upon us as the West and would like to serve their own interests. That is why we reject Communism. "[91] His governance was often criticised by communists and other leftists, some of whom accused him of being a fascist.[27] When Chinese Communist official Zhou Enlai visited Dar es Salaam, his statement that "Africa is ripe for revolution" was clearly aimed largely at Kenya.[27] In 1964, Kenyatta impounded a secret shipment of Chinese armaments that passed through Kenyan territory on its way to Uganda. Obote personally visited Kenyatta to apologize.[92] In June 1967, Kenyatta declared the Chinese Chargé d'Affairs persona non grata in Kenya and recalled the Kenyan ambassador from Peking.[27] Relations with the Soviet Union were also strained; Kenyatta shut down the Lumumba Institute—an organisation named after the Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba—on the basis that it was a front for Soviet influence in Kenya.[93]

Dissent and the one-party state

[edit]

Kenyatta made clear his desire for Kenya to become a one-party state, regarding this as a better expression of national unity than a multi-party system.[94] In the first five years of independence, he consolidated control of the central government,[95] removing the autonomy of Kenya's provinces to prevent the entrenchment of ethnic power bases.[96] He argued that centralised control of the government was needed to deal with the growth in demands for local services and to assist quicker economic development.[96] In 1966, it launched a commission to examine reforms to local government operations,[96] and in 1969 passed the Transfer of Functions Act, which terminated grants to local authorities and transferred major services from provincial to central control.[97]

A major focus for Kenyatta during the first three and a half years of Kenya's independence were the divisions within KANU itself.[98] Opposition to Kenyatta's government grew, particularly following the assassination of Pio Pinto in February 1965.[9] Kenyatta condemned the assassination of the prominent leftist politician, although UK intelligence agencies believed that his own bodyguard had orchestrated the murder.[99] Relations between Kenyatta and Odinga were strained, and at the March 1966 party conference, Odinga's post—that of party vice president—was divided among eight different politicians, greatly limiting his power and ending his position as Kenyatta's automatic successor.[100] Between 1964 and 1966, Kenyatta and other KANU conservatives had been deliberately trying to push Odinga to resign from the party.[101] Under growing pressure, in 1966 Odinga stepped down as state vice president, claiming that Kenya had failed to achieve economic independence and needed to adopt socialist policies. Backed by several other senior KANU figures and trade unionists, he became head of the new Kenya Peoples Union (KPU).[102] In its manifesto, the KPU stated that it would pursue "truly socialist policies" like the nationalization of public utilities; it claimed Kenyatta's government "want[ed] to build a capitalist system in the image of Western capitalism but are too embarrassed or dishonest to call it that."[103] The KPU were legally recognized as the official opposition,[104] thus restoring the country's two party system.[105]

The new party was a direct challenge to Kenyatta's rule,[105] and he regarded it as a communist-inspired plot to oust him.[106] Soon after the KPU's creation, the Kenyan Parliament amended the constitution to ensure that the defectors—who had originally been elected on the KANU ticket—could not automatically retain their seats and would have to stand for re-election.[107] This resulted in the election of June 1966.[108] The Luo increasingly rallied around the KPU,[109] which experienced localized violence that hindered its ability to campaign, although Kenyatta's government officially disavowed this violence.[110] KANU retained the support of all national newspapers and the government-owned radio and television stations.[111] Of the 29 defectors, only 9 were re-elected on the KPU ticket;[112] Odinga was among them, having retained his Central Nyanza seat with a high majority.[113] Odinga was replaced as vice president by Joseph Murumbi,[114] who in turn would be replaced by Moi.[115]

Legacy

[edit]

Within Kenya, Kenyatta came to be regarded as the "Father of the Nation",[116] and was given the unofficial title of Mzee, a Swahili term meaning "grand old man".[117] From 1963 until his death, a cult of personality surrounded him in the country,[118] one which deliberately interlinked Kenyan nationalism with Kenyatta's own personality.[118] This use of Kenyatta as a popular symbol of the nation itself was furthered by the similarities between their names.[119] He came to be regarded as a father figure not only by Kikuyu and Kenyans, but by Africans more widely.[120]

After 1963, Maloba noted, Kenyatta became "about the most admired post-independence African leader" on the world stage, one who Western countries hailed as a "beloved elder statesman."[121] His opinions were "most valued" by both conservative African politicians and Western leaders.[122] On becoming Kenya's leader, his anti-communist positions gained favor in the West,[123] and various pro-Western governments gave him awards; in 1965 he, for instance, received medals from both Pope Paul VI and the South Korean government.[124]

In 1974, Arnold referred to Kenyatta as "one of the outstanding African leaders now living", someone who had become "synonymous with Kenya".[125] He added that Kenyatta had been "one of the shrewdest politicians" on the continent,[126] regarded as "one of the great architects of African nationalist achievement since 1945".[127] Kenneth O. Nyangena characterised him as "one of the greatest men of the twentieth century", having been "a beacon, a rallying point for suffering Kenyans to fight for their rights, justice and freedom" whose "brilliance gave strength and aspiration to people beyond the boundaries of Kenya".[128] In 2018, Maloba described him as "one of the legendary pioneers of modern African nationalism".[129] In their examination of his writings, Berman and Lonsdale described him as a "pioneer" for being one of the first Kikuyu to write and publish; "his representational achievement was unique".[130]

President Jomo Kenyatta had a mixed legacy. Although he was sometimes lauded as a freedom fighter in league with the Mau Mau, post independence events would show otherwise. On 12 December 1964, President Kenyatta issued an amnesty to Mau Mau fighters to surrender to the government. Some Mau Mau members insisted that they should get land and be absorbed into the civil service and Kenya army. On 28 January 1965, the Kenyatta government sent the Kenya Army to Meru district, where Mau Mau fighters gathered under the leadership of Field Marshall Mwariama and Field Marshall Baimungi. These leaders and several Mau Mau fighters were killed. On 14 January 1965, the Minister for Defence Dr Njoroge Mungai was quoted in the Daily Nation saying: "They are now outlaws, who will be pursued and brought to punishment. They must be outlawed as well in the minds of all the people of Kenya."[131][132] President Kenyatta's mixed legacy was highlighted at the 10-year anniversary of Kenya's independence. An article published in The New York Times in December 1973 praised Kenyatta's leadership and Kenya for emerging as a model of pragmatism and conservatism. Kenya's GDP had increased at a rate of 6.6 per cent a year, higher than the population growth rate of more than 3 per cent.[133] However, Amnesty International responded to this article by stating the cost of the stability in terms of human rights abuses. The opposition party started by Oginga Odinga – Kenya People's Union (KPU) – was banned in 1969 following the Kisumu massacre and KPU leaders were still in detention without trial in gross violation of the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights. The Kenya Students Union, Jehovah Witnesses and all opposition parties were outlawed.[134][135] The high-profile assassinations of Pio Gama Pinto and Josiah Mwangi Kariuki, which directly benefited Kenyatta and his ilk, also taint his record.[136][137]

Jomo Kenyatta did not change the colonial socio-political and economic order despite the post-independence hype and expectations. Excessive power was centered on the Kenyatta's person and this led to the replacement of European elites by an African elite allied to Kenyatta, mainly from his own tribe. Checks and balances to contain the Executive eroded considerably. These aspects of Kenyatta's presidency carried forward into the Moi era and continue to affect Kenya today.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Elections in Africa : a data handbook. Nohlen, Dieter., Krennerich, Michael., Thibaut, Bernhard. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1999. ISBN 0198296452. OCLC 41431601.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "EISA Kenya: One party elections (1969–1988)". eisa.org.za. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Key dates in Kenya's history". Daily Nation. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ The table shows the names and positions of the first cabinet of Kenya formed in 1963 by Kenyatta at the beginning of his first term

- ^ Gertzel 1970, p. 35.

- ^ Ochieng 1995, p. 94; Gertzel 1970, p. 152.

- ^ Assensoh 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Murray-Brown 1974, p. 316; Maloba 2017, p. 340.

- ^ a b c Murray-Brown 1974, p. 316.

- ^ Murray-Brown 1974, p. 313; Assensoh 1998, p. 63.

- ^ a b Murray-Brown 1974, p. 312.

- ^ Murray-Brown 1974, pp. 312–313; Assensoh 1998, p. 63.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 168; Ochieng 1995, p. 93; Assensoh 1998, p. 63.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 112.

- ^ a b Maxon 1995, p. 115.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 138.

- ^ a b Maxon 1995, p. 139.

- ^ a b Maxon 1995, p. 140.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 141.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 142.

- ^ Ochieng 1995, p. 83.

- ^ Ochieng 1995, pp. 90, 91.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 84; Maxon 1995, p. 115; Maloba 2017, p. 6.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 208.

- ^ a b c Ochieng 1995, p. 85.

- ^ Arnold 1974, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b c d Arnold 1974, p. 177.

- ^ Ochieng 1995, p. 91.

- ^ Ochieng 1995, p. 83; Assensoh 1998, p. 64; Maloba 2017, p. 77.

- ^ Savage 1970, p. 520; Ochieng 1995, p. 84.

- ^ Ochieng 1995, p. 84; Assensoh 1998, p. 64.

- ^ Ochieng 1995, p. 96.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Savage 1970, p. 521.

- ^ Assensoh 1998, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c Savage 1970, p. 522.

- ^ a b Assensoh 1998, p. 64.

- ^ Savage 1970, p. 521; Ochieng 1995, p. 85; Maxon 1995, p. 114; Assensoh 1998, p. 64.

- ^ Murray-Brown 1974, p. 316; Arnold 1974, p. 170.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 114.

- ^ a b Arnold 1974, p. 172.

- ^ Maloba 2017, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Maloba 2017, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 241.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 238.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 242.

- ^ Maloba 2017, pp. 242–244.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 236.

- ^ Maloba 2017, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Maloba 2017, pp. 246–247, 249.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 195.

- ^ a b Arnold 1974, p. 196.

- ^ a b Boone 2012, p. 81.

- ^ a b Boone 2012, p. 82.

- ^ Boone 2012, p. 85; Maloba 2017, p. 251.

- ^ Maxon 1995, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Maxon 1995, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 126.

- ^ Savage 1970, p. 523; Maloba 2017, p. 91.

- ^ Savage 1970, p. 523.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 113.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 118.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 120.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 110.

- ^ Maxon 1995, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Maxon 1995, p. 127.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 127; Assensoh 1998, p. 147.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 128.

- ^ a b Maxon 1995, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Maxon 1995, p. 133.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 134.

- ^ Maxon 1995, p. 122.

- ^ Maxon 1995, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 167.

- ^ Murray-Brown 1974, p. 320.

- ^ a b Arnold 1974, p. 175.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 178.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d Cullen 2016, p. 515.

- ^ Cullen 2016, p. 515; Maloba 2017, p. 96.

- ^ Murray-Brown 1974, p. 313.

- ^ Arnold 1974, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 54.

- ^ Cullen 2016, p. 514.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 296.

- ^ Maloba 2017, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Naim 2005, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Naim 2005, pp. 79–80; Maloba 2017, pp. 190–193.

- ^ Maloba 2017, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 167; Assensoh 1998, p. 147.

- ^ Savage 1970, p. 527; Maloba 2017, p. 76.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 177; Maloba 2017, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 160; Maloba 2017, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Murray-Brown 1974, p. 314.

- ^ Boone 2012, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Assensoh 1998, p. 18.

- ^ Assensoh 1998, p. 19.

- ^ Gertzel 1970, p. 32.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 68.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 161; Maloba 2017, p. 105–106.

- ^ Maloba 2017, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Gertzel 1970, p. 32; Savage 1970, p. 527; Murray-Brown 1974, p. 317; Arnold 1974, p. 164; Assensoh 1998, p. 67; Maloba 2017, p. 108.

- ^ Ochieng 1995, pp. 99, 100.

- ^ Gertzel 1970, p. 146.

- ^ a b Gertzel 1970, p. 144.

- ^ Ochieng 1995, p. 98.

- ^ Gertzel 1970, p. 35; Maloba 2017, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Gertzel 1970, p. 35; Maloba 2017, p. 111.

- ^ Murray-Brown 1974, p. 318.

- ^ Gertzel 1970, p. 147.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 119.

- ^ Savage 1970, p. 527; Maloba 2017, p. 125.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 164.

- ^ Assensoh 1998, p. 67.

- ^ Assensoh 1998, p. 67; Maloba 2017, p. 138.

- ^ Murray-Brown 1974, p. 315; Arnold 1974, p. 166; Bernardi 1993, p. 168; Cullen 2016, p. 516.

- ^ Jackson & Rosberg 1982, p. 98; Assensoh 1998, p. 3; Nyangena 2003, p. 4.

- ^ a b Maloba 2018, p. 4.

- ^ Jackson & Rosberg 1982, p. 98.

- ^ Arnold 1974, pp. 192, 195.

- ^ Maloba 2018, p. 2.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 196.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Maloba 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 9.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 209.

- ^ Arnold 1974, p. 192.

- ^ Nyangena 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Maloba 2018, p. 1.

- ^ Berman & Lonsdale 1998, p. 17.

- ^ Angelo, Anaïs (3 July 2017). "Jomo Kenyatta and the repression of the 'last' Mau Mau leaders, 1961–1965". Journal of Eastern African Studies. 11 (3): 442–459. doi:10.1080/17531055.2017.1354521. ISSN 1753-1055. S2CID 148635405.

- ^ Kenya National Assembly Official Record. 12 July 2000. Parliamentary debates. page 1552-1553

- ^ "Kenya, 10 Years Independent, Emerges as a Model of Stability". The New York Times. 16 December 1973. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Kenya's Costly 'Stability'". Letters to the Editor. The New York Times. 28 December 1973.

- ^ "Amnesty International Annual Report 1973-1974".

- ^ Branch, Daniel (November 2011). "Freedom and suffering". Kenya: Between Hope and Despair, 1963 – 2011. Yale University Press.

- ^ Otzen, Ellen (11 March 2015). "Kenyan MP's murder unsolved 40 years on". BBC World Service.

References

[edit]- Assensoh, A. B. (1998). African Political Leadership: Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, and Julius K. Nyerere. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 9780894649110.

- Lonsdale, John (1990). "Mau Maus of the Mind: Making Mau Mau and Remaking Kenya". The Journal of African History. 31 (3). Cambridge University Press: 393–421. doi:10.1017/s0021853700031157. hdl:10539/9062. ISSN 0021-8537.

- Lonsdale, John (2006). "Ornamental Constitutionalism in Africa: Kenyatta and the Two Queens". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 34 (1). Informa UK Limited: 87–103. doi:10.1080/03086530500412132. ISSN 0308-6534. S2CID 153491600.

- Maloba, W. O. (2017). The Anatomy of Neo-Colonialism in Kenya: British Imperialism and Kenyatta, 1963–1978. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3319509648.

- Maloba, W. O. (2018). Kenyatta and Britain: An Account of Political Transformation, 1929–1963. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3319508955.

- Maxon, Robert M. (1995). "Social and Cultural Changes". In Ogot, B. A.; Ochieng, W. R. (eds.). Decolonization and Independence in Kenya 1940–93. Eastern African Series. London: James Currey. pp. 110–147. ISBN 978-0821410516.

- Murray-Brown, Jeremy (1974) [1972]. Kenyatta. New York City: Fontana. ISBN 978-0006334538.

- Naim, Asher (2005). "Perspectives—Jomo Kenyatta and Israel". Jewish Political Studies Review. 17 (3). Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs: 75–80. ISSN 0792-335X. JSTOR 25834640.

- Ochieng, William R. (1995). "Structural and Political Changes". In Ogot, B. A.; Ochieng, W. R. (eds.). Decolonization and Independence in Kenya 1940–93. Eastern African Series. London: James Currey. pp. 83–109. ISBN 978-0821410516.

- Polsgrove, Carol (2009). Ending British Rule in Africa: Writers in a Common Cause. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719089015.

- Savage, Donald C. (1970). "Kenyatta and the Development of African Nationalism in Kenya". International Journal. 25 (3): 518–537. doi:10.2307/40200855. ISSN 0020-7020. JSTOR 40200855.