Potato cooking

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

The potato is a starchy tuber that has been grown and eaten for more than 8,000 years. In the 16th century, Spanish explorers in the Americas found Peruvians cultivating potatoes and introduced them to Europe. The potato, an easily grown source of carbohydrates, proteins and vitamin C, spread to many other areas and became a staple food of many cultures. In the 20th century potatoes are eaten on all continents; the method of preparation, however, can modify its nutritional value.

Prepared in its skin or peeled and cooked by methods including boiling, grilling, sautéing, and frying, the potato is used as a main dish or as a side dish, or as an ingredient. It is also used as a thickener, or for its by-products (starch or modified starches).

Ancient preparations

[edit]Peru

[edit]Joseph Dombey, in a letter written from Lima on May 20, 1779, specifies the ancestral way used by the Peruvians to prepare potatoes that constitute, with corn, their only food and that they carry in a haversack during their long journeys: the potato is cooked in water, then peeled and exposed to the wind and the sun until it is completely dry, which allows to preserve it "several centuries, by guaranteeing it of the humidity".[1] This papa seca is mixed with other foods for consumption.[2] Another process consists of freezing the potato and treading on it to remove the skin. Thus prepared, it is put in running water and loaded with stones. Fifteen or twenty days later, it is exposed to the sun until it dries. It becomes the chuño, "a real starch, with which one could make powder for the hair".[1] The Peruvians use it to prepare jams, a flour for convalescents, and mix it with almost all their dishes.

-

Chuño, also called black chuño

-

Tunta, also called white chuño

-

Other tunta.

An author of the 20th century points out that the process of the Peruvians, who operate by freezing followed by dehydration, is not other than "a freeze-drying by the natural means".[3] He specifies that the tubers are left in frozen water several nights before being exposed to the sun and trodden on and that, "to make the product suitable for consumption, it is enough to put it back in water". According to him, the Spaniards used this preparation in the 16th century to feed the indigenous people forced to work in the silver mines of Potosi.

Chuño is still produced in the Andean Altiplano, specifically in the Suni and Puna regions, which are the only regions with suitable eco-climatic conditions,[4] and is consumed in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Peru. According to the botanist Redcliffe Salaman, in prehistoric times, chuño was ground into flour and incorporated into all kinds of stews and chupes, a kind of hearty soup of very ancient origin, but still cooked.[5]

Another traditional product of the Altiplano is tocosh, obtained from the fermentation of potatoes left in a stream of water for at least six months. This product, considered to have probiotic properties, is used in the preparation of a local dessert, the mazamorra de papas.[6]

Principality of Liege

[edit]

It seems that the first book to give recipes for potatoes was written by the chef of three successive prince-bishops of the Principality of Liège: the Ouverture de cuisine of Lancelot de Casteau, published in 1604, which gives four ways of cooking this plant, which was still exotic for Europe:

Boiled potatoes. Take a thoroughly washed potato and boil it in water; when it is ready, it needs to be cleaned, cut, greased with butter and pepper. (French: Tartoufle boullye. Prennez tartoufle bien lauee, & la mettez boullir dedans eau, eſtant cuite il la faut peler & coupper par tranches, beurre fondu par deſſus, & poiure.)

Otherwise: Cut the potato into slices as shown above, stew with Spanish wine, oil and nutmeg. (French: Tartoufle autrement. Conppez la tartoufle par tranches comme deſſus, & la mettez eſteuuer avec vin d'Eſpagne & nouveau beure, & noix muſcade.)

Take potato slices, stew them with butter, chopped marjoram and parsley; simultaneously whisk four or five egg yolks with a little wine, pour them into the boiling potatoes, remove from heat and serve. (French: Autrement. Prennez la tartoufle par tranches, & mettez eſteuuer auec beurre, mariolaine haſchee, du persin : puis prennez quatre ou cinq iaulnes d'œuf battus auec vn peu de vin, & iettez le deſſus tout en bouillãt, & tirez arriere du feu, & seruez ainsi.)

Otherwise: Roast the potatoes like chestnuts in the ashes, peel and cut into slices. Sprinkle with chopped mint, pour boiled raisins, vinegar and sprinkle with pepper. (French: Autrement. Mettez roſtir la tartoufle dedans le cendres chaudes comme on cuit les caſtaignes, puis la faut peler & coupper par trãches, mettez ſus mente haſchee, des carentines boullies par deſſus, & vinaigre, vn peu de poiure, & ſeruez ainſi.)

The absence of salt in the seasoning is justified by the fact that the salt present in the butter at the time was sufficient.

Lancelot de Casteau makes no comment on the vegetable, its origin, its price, or the ease or difficulty of finding it on the market. However, he has been using potatoes since at least December 12, 1557, since the dish "boiled potato" appears in the third course of the banquet that he organized on that date for the Joyous Entry of Prince-Bishop Robert of Berghes. As a court cook, he had to use quality products while keeping a reasonable budget, as he worked on his own funds and was only paid after presenting his statement of fees.

The potato was cooked in the Principality of Liege sixty years before being offered "as a rarity at the table of the king" of France Louis XIII, in 1616.[1]

Ireland

[edit]

In Ireland, the potato was introduced at the end of the 16th century and quickly became the main staple food until the end of the 19th century.

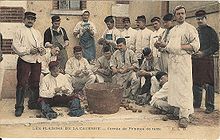

Among the peasants, it appears at every meal and in one form, the simplest possible, boiled in water. The tubers, with their skins, are cooked in a cauldron, the only utensil necessary for their preparation, in a bottom of water. After cooking, the contents of the cauldron are poured into a shallow wicker basket, called a skeehogue, which allows for easy draining, and the whole family, sitting around the basket in front of the fireplace, serves itself with its hands, without fork or knife.[7]

In more affluent homes, where people eat at the table, another characteristic utensil is used: a trivet in the form of a fairly high ring (dish ring). Often made of silver and richly decorated, its function was to protect the tabletop from the heat.

In 1740, a shortage of potatoes led to a famine in the country – although on a smaller scale than the one that hit Europe – in Ireland in 1845, causing nearly a million deaths and several million refugees and emigrants.

Slow appropriation in France

[edit]

Arrived in Europe in the 16th century, this solanaceous plant (with a pink skinned tuber in England and a yellow skin in Spain) spread in the Principality of Liege, Ireland, Flanders, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, etc.

In France, its resemblance with toxic species (for example the daturas, known for their toxicity to livestock, but also to humans) and the lack of techniques of conservation and use, are brakes to its cultivation, beside purely agronomic reasons (bad ecological adaptation) or religious (non-perception of the tithe on this food). In the Théâtre d'agriculture et Mesnage des champs, published in 1600, Olivier de Serres already recommended the cultivation of the "white truffle" or "cartoufle" and found it to have a flavor worthy of the best black truffles.[8] Around 1750, the cultivation and consumption of tubers were recommended by several people or institutions: Duhamel du Monceau, the bishops of Albi and Léon, the minister Turgot, Rose Bertin, the Agricultural Society of Rennes. Ten years before the publications of Antoine Parmentier and Samuel Engel, Duhamel du Monceau "strongly exhorts farmers not to neglect the cultivation of this plant" and remarks that "it is an excellent food especially with a little bacon and salted pork".[7]

But the French population remains more than reticent before this dish: the majority of French people still disdain it as a food for humans, even if it is cultivated and used in some regions. However, this vegetable is an alternative to wheat, the food base whose lack has caused shortages for centuries, which will lead to the Great Fear or an increase in the price of bread, such as it will be one of the popular reasons for the support of the people to the bourgeoisie during the French Revolution, the hungry crowd going to Versailles to get the "Boulanger" (Louis XVI), the "Boulangère" (Marie-Antoinette) and the "Petit Mitron" (the dauphin).[9]

According to contemporaries:

most of the farmers, who are not sufficiently educated, follow mechanically and without reflection, the practice of their small township or the method of their old relatives. A new culture would require a tiring study. [...] But in vain would one cultivate, in vain would one multiply this salutary commodity, if the people themselves, if the poorest citizens, stubborn of an absurd prejudice, refused, disdained to consume it. We have seen them, in times of the cruellest famine, rejecting the potato with fury, and shouting that we wanted to poison them. (French: la plupart des cultivateurs, trop peu instruits, suivent machinalement et sans réflexions, la pratique de leur petit canton ou la méthode de leurs vieux parens. Une nouvelle culture leur demanderoit une étude fatigante. […] Mais en vain cultiveroit-on, en vain multiplieroit-on cette denrée salutaire, si le peuple lui-même, si les citoyens les plus pauvres, entêtés d'un préjugé absurde, refusoient, dédaignoient de la consommer. On les a vus, dans les temps de la plus cruelle disette, repousser avec fureur la pomme de terre, et crier qu'on les vouloit empoisonner.)

To these words, La Feuille villageoise adds: "The example of honest, good farmers and landlords will suffice to familiarize the most stubborn day laborer with this new food; we could also use the ingenious means that were used in Ireland to accustom the least educated and least well-to-do portion of the people. In the schools, when a child had learned his lesson well, he was given a potato as a reward. When he had earned the prize for wisdom as well as for memory, he was given several; he ate them with delight; his classmates envied him, or feasted on the portion he was willing to give them. Sometimes he brought his apple home; the parents tasted it and found it good. Insensibly, the general repugnance of the people fell away, and it was not two generations before the potato became the favorite stew of the Irish."[10]

Invention of products

[edit]In the 18th century, the potato was actively studied in all its practical aspects: cultivation and reproduction, diseases, use as a food for animals and as a vegetable for humans. Its use was also considered in the same way as that of cereals which produce flour – and therefore bread – but also alcohol. Other uses and by-products were born, some of which still exist in the 21st century.

Starch

[edit]

As early as 1731, starch was extracted from the potato and used as a substitute for wheat starch.[11]

It is also used in pastries and cookies; it is in particular an ingredient of the Gâteau de Savoie; it is added, mixed with water, to omelets and is used for sauces in smaller quantities than flour.[12]

Potato starch was used to produce artificial honey that looked like honey from Narbonne.[13] It is still abundantly produced in the 21st century. The extraction of this starch gives rise to an important industrial activity: the "starch factory".

Bread

[edit]

In 1771, Samuel Engel mentions, in his Traité de la nature, de la culture, et de l'utilité des pommes de terre par un ami des hommes, that half of Europeans live on bread and the other half on potatoes, and also that bread is made by mixing a third or a quarter of potato with cereal flour, which gives a dish "preferred by taste, to bread of pure wheat".

He refers to various authors, including François Mustel who wrote Mémoire sur les pommes de terre et sur le pain économique. Mustel invented, before 1766, a kind of inverted jointer plane to grate potatoes, peeled or not, into a fine mush that must be mixed with wheat flour: the proportion of one 1/3 flour to 2/3 potatoes gives an edible bread he says, 50% of each ingredient a good one, and at the rate of 2/3 to 1/3, it is difficult to notice that the bread is not pure wheat; the mixture must be kneaded with ordinary sourdough, but less water is used and less heat is applied, which produces an additional saving; this bread keeps fresher for longer, it remains edible for fifteen days, instead of six for traditional bread. This prolongation of freshness, which is very appreciable, encourages many Ardennes farmers to add to their bread, until the 1980s, some 10% of potatoes,[14] the Gaumais going up to 50%.[15]

Research on the use of the tuber for bread making was numerous in France at the end of the 18th century, but this did not lead to the massive perpetuation of this practice. A newspaper of 1847 makes an argument on this subject: "In Scotland, in England, in Holland, in Germany, in Prussia, on the coast of the Baltic, the greater part of the population lives on potatoes during six to seven months of the year. Nowhere is bread made from them. France, which was the last to accept the potato as a food substance, is also the first to use it for a purpose that cannot be profitable. What is the use of going to so much trouble to spoil what is good?"[16]

Potato bread remains in family or regional use: thus we note the Correzian farcidure, Norwegian lefse and Rēwena bread.

Alcohol

[edit]

Antoine Parmentier tried to make alcohol and beer from the potato, having learned that in other countries it was being distilled, but he admitted his failure in 1773.[17] Two years before, the Encyclopédie Méthodique reported that potato eau de vie was well known to the Swedes and other Europeans.[1]

Five methods are listed in 1839, in the Dictionnaire technologique:[18]

- By three maneuvers: cooking potatoes, reduction to mush, maceration by malted barley;

- By conversion of the starch into syrup by sulfuric acid;

- By saccharification of cooked potato slurry with sulfuric acid;

- By saccharification of potato pulp with caustic potash;

- By saccharification of potato flour with sulfuric acid.

In 1913, Antonin Rolet gave two recipes for potato starch beer, one made from hops and starch, the other from hops, starch and malt flour, for use by families and agricultural cooperatives.[19]

In the 21st century, aquavit, vodka, poteen and härdöpfeler are still produced from potatoes. These spirits can be used in cooking for deglazing or flambéing.

Cheese

[edit]Louis de Jaucourt, in the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, cites a German who invented a way to make three cheeses, from large potatoes boiled in their skins, then peeled and ground with a spoon before being mixed with curdled milk; the cheeses obtained acquire more quality and finesse as they age.[14]

The Encyclopédie Méthodique, which includes this information, specifies the proportions according to which the cheese is intended for the poor (five pounds of vegetables for one pound of curd), for everyone (four pounds for two pounds of curd), or for the best tables (two pounds for four pounds of milk); by adding cream, large cheeses like those of Holland are made. She says that sheep's or goat's milk gives better results than cow's milk.[1]

Coffee

[edit]According to the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, the Germans use potatoes as coffee, either by using the whole tuber, boiled, scraped, cut into small cubes and put to dry, or by using the peels, chopped and dried; in both cases, the dried material is roasted, ground, prepared and served like ordinary coffee, with cream for those who prefer it.[14]

Potato syrup

[edit]This potato syrup replaces sugar and sugar syrup. It is used in baking. In the Netherlands, the production of potato syrup started in 1819 in Gouda where the first starch and sugar factory was built.[20]

An 18th century menu

[edit]

After having tried for a long time to make bread with potatoes, Antoine Parmentier understood that this tuber should be considered as a versatile vegetable, and that its use required the popularization of recipes that would make it a main food.

In his Examen chymique des pommes de terre published in 1773,[17] he cites (but without giving the precise date) the composition of a menu that he had served to friends:[21]

The ease with which our potatoes lend themselves to all sorts of stews gave me the idea of composing a meal of them, to which I invited several amateurs; and at the risk of being thought to be afflicted with potato mania, I will end this review by describing it: it was a dinner. We were first served two soups, one of mashed potatoes from our roots, the other of a fatty broth, in which the potato bread simmered quite well without crumbling; then came a matelote followed by a dish in white sauce, then another in maitre d'hôtel, and finally a fifth in roux. The second service consisted of five other dishes not less good than the first; first a pâté, a frying, a salad, fritters, and the economic cake of which I gave the recipe; the remainder of the meal was not very extensive, but delicate and good; a cheese, a pot of jam, a plate of cookie, another of tarts, and finally a brioche also of potatoes, made up the dessert; after that we had the coffee, also described above. There were two kinds of bread; the one mixed with potato pulp and wheat flour, fairly represented soft bread; the second, made of potato pulp, with their starch, bore the name of firm dough bread; I would have wished that fermentation had put me in a position to make a drink of our roots, to fully satisfy my guests, and to say with foundation: "Do you like potatoes, we have put them everywhere." Every one was cheerful; and if potatoes are drowsy, they produce on us a very opposite effect.

By applying Menon's idea of creating a meal based on a single food, as this culinary writer had indicated in 1755, in Les Soupers de la cour ou l'art de travailler toutes sortes d'aliments pour servir les meilleures tables, suivant les quatre saisons with his Menu d'un repas servi tout en mouton, Menu d'un repas servi tout en cochon and Menu d'un repas servi tout en œufs, Parmentier demonstrates to a group of influential people in good society, including Nicolas François de Neufchâteau,[22] that the potato can be used, in different forms, at different times of the meal. He thus succeeded in promoting the vegetable on the culinary level, which still leaves its mark on people's minds for a long time to come: "The guests, who were all distinguished men, people in credit or people of spirit, went to the fashionable salons to tell the news of their dinner where the potato reigned without rival", wrote the Semaine des familles, nearly a century later.[23]

Parmentier took every opportunity to promote the tuber: when he received Arthur Young on October 24, 1787, the menu was based on potatoes and, for the first time, his sister Marie-Suzanne Houzeau served, among other dishes, steamed potatoes.[24]

However, the use of this tuber did not become widespread in France until the end of the 19th century, when Alexandre Dumas felt the need to affirm its healthiness:[25]

The potato is really a healthy, easy and inexpensive food. The preparation of potatoes is pleasant and advantageous for the working class, as it requires almost no care and expense. The eagerness with which one sees children eating potatoes cooked under the ashes and finding themselves well, proves enough that they are suitable for all constitutions

Nutritional aspects

[edit]Influence of preparation methods

[edit]Depending on the preparation and cooking methods, the nutritional value of potatoes can vary greatly. In particular, its energy content, moderate in comparison with other starchy foods, can increase considerably when cooked with fat, and its vitamin content is affected to a greater or lesser extent depending on the cooking method. However, cooking is essential to make it an appetizing and especially digestible food.

In the raw potato, the starch is mainly in the form of resistant starch, so called because it resists digestive enzymes such as amylase. Under the effect of heat, around 50 °C, the amylose swells and causes the starch grains to burst, which "gelatinize" and lose their "resistant" character. However, when the preparation is subsequently cooled, e.g. in salads, the proportion of resistant starch increases due to a retrogradation of the amylose. In boiled potatoes, this proportion can be about 2% (of the total starch) and in potato salad it can be as high as 6%.[26] The resistant starch remains intact in the large intestine, playing a role similar to that of dietary fiber, which may be of interest in some diets.

A 100 g portion of potatoes simply boiled in their skins provides 76 kcal, which is comparable to corn porridge, also 76 kcal, or plantain (94), but is significantly lower than the same portion of dried beans (115), pasta (132), rice (135) or bread (278). They are often paired or cooked with dietary fats, which can significantly increase the potato dishes caloric value.

Cooking in water causes the loss of some of the water-soluble elements, in particular vitamin C, especially when the tubers are peeled. Thus, in the case of a cooking of 25 to 30 minutes in boiling water, peeled potatoes can lose up to 40% of their vitamin C, 10% if they are cooked with the skin (in this last case, there remains 13 mg of vitamin C for 100 g of vegetable). These losses are added to those induced by the storage time, about 50% after three months.[27] Other preparation methods are even more aggressive for vitamin C, but also for B vitamins; for example, pureeing causes up to 80% loss in vitamin C, and frying 60%.

Nevertheless, a 100 g serving of processed potato products can provide 10–50% of the recommended daily allowance of vitamin C for an adult.

Cooking with fat, especially frying, can lead to the formation of acrylamide, a substance that is probably carcinogenic to humans, especially if cooked for too long at high temperatures. This reaction occurs when potatoes contain too many reducing sugars (glucose and fructose); their rate, which should not exceed 0.4 to 0.6% of the fresh weight,[28] depends on the variety, the maturity of the tubers and the storage conditions, low temperatures, below 8 °C, favoring the retrogradation of the starch into reducing sugars.

The potatoes known as "for consumption", i.e. which were harvested with complete maturity, can be preserved several weeks, provided that they are stored in a room that is ventilated, fresh (between 8 and 9 °C) but sheltered from the frost, and obscure because the light makes them green. Early potatoes, harvested before maturity, cannot be stored. They can be kept for a few days at most in the refrigerator crisper drawer.[29]

| Cooking method | Energy kcal | Water g | Carbohydrates g | Lipids g | Proteins g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| raw | 80 | 78.0 | 18.5 | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| boiled with skin | 76 | 79.8 | 18.5 | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| boiled without skin | 72 | 81.4 | 16.8 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| in the oven (dry) | 99 | 73.3 | 22.9 | 0.1 | 2.5 |

| Mashed | 106 | 78.4 | 15.2 | 4.7 | 1.8 |

| Home fries | 157 | 64.3 | 27.3 | 4.8 | 2.8 |

| Fried | 264 | 45.9 | 36.7 | 12.1 | 4.1 |

| Chips | 551 | 2.3 | 49.7 | 37.9 | 5.8 |

Associated ingredients

[edit]Among the ingredients often associated with the potato, for example in various regional specialties, are milk and dairy products. These compensate for the deficiency of the tuber in vitamins A and D, and complete the dish in proteins, lipids and calcium. This explains why entire populations in Ireland and northern Europe have been able to subsist on a diet based almost exclusively of potatoes and milk.[31]

Processed products

[edit]More and more, potatoes are consumed and cooked through industrially processed products, mainly frozen products, most often precooked, or dehydrated (e.g., potato flakes, granules, flour).

The share of processed products exceeds that of table potatoes in some Western countries (United States, Canada, Northern Europe). In Germany, for example, in 2003–2004, processed potatoes accounted for 34.3 kg per capita per year, compared to 32.5 kg for table potatoes.[32] In the United States, the use of fresh potatoes represented, in 2007, only one third of the total consumption.

Most of the time, these are "ready to cook" products, which have the advantage of facilitating the preparation of meals, eliminating the need for tedious peeling, and which can be stored more easily and longer than fresh tubers. The most commonly used are dehydrated flaked mashed potatoes, or instant mashed potatoes, and pre-cooked frozen French fries. The latter are more commonly consumed in the catering industry. The simplest are peeled and pre-cooked vacuum-packed potatoes, which belong to the category of fresh products, known as fifth range. Canned potatoes (tins or jars) are also available on the market, sometimes mixed with carrots or peas.

Potato chips are a special case, since this product is consumed directly, without any culinary preparation, and most often outside the meal.

Before cooking

[edit]Peeling

[edit]

For many traditional recipes potatoes are peeled, which can be used to remove the green parts that contain solanine, a neurotoxin present in the potato's skin and sometimes the flesh.[33]

Industrial peeling

[edit]Efficient techniques have been developed by the industry to peel large quantities of tubers while limiting losses and waste that must then be recycled, usually in animal feed. These techniques are abrasive peeling (the one that produces the most losses), soda peeling (chemical peeling by soaking in a bath of sodium hydroxide at high temperature, followed by rinsing), or steam peeling (a high-pressure steam bath removes the skin from the tubers, which is then vacuumed). The latter method minimizes vitamin losses.[34]

Peelings

[edit]Generally treated as waste, potato peels can also be cooked, in times of shortage or in the context of cooking leftovers. In addition to the cases where the tubers are cooked and served with their skins, for example new potatoes, one can also make appetizers in the form of potato peel chips, or fritters, by dipping peels taken from boiled potatoes in a fritter batter. Baked potatoes cut in half and scooped out with a spoon can be used to make nests, which can be stuffed with other ingredients, such as a poached egg in the case of Oeufs Toupinel.[35]

Bibliography

[edit]- Cécile Allegri, Claire Brosse, Federico Oldenburg and Hervé Robert, La Pomme de terre, saveurs méditerranéennes, Éditions du Bottin Gourmand, coll. « Les essentiels du goût », 2003, 99 p. (ISBN 2-913306-61-6).

- Joseph Bonjean, Monographie de la pomme de terre envisagée dans ses rapports agricoles, scientifiques et industriels et comprenant l'histoire générale de la maladie des pommes de terre en 1845, Paris, Germer Baillière, 1846, 306 p.

- Collective, La Pomme de terre. Histoire et recettes gourmandes, Grenoble, Glénat, 2009, 160 p. (ISBN 2-7234-7319-8).

- Collective, La Pomme de terre, un tour du Monde en 200 recettes, Geneva, United Nations, 2008, 360 p. (ISBN 92-1-200373-7).

- Lucienne Desnoues, Toute la pomme de terre, Paris, Mercure de France, 1978, 302 p.

- Qu Dongyu et Xie Kaiyun, How the Chinese Eat Potatoes, Singapour, World Scientific Publishing Company, 2009, 432 p. (ISBN 981-283-291-2).

- Jean Ferniot (pref. Joël Robuchon), Chère pomme de terre, First, 1996, 301 p. (ISBN 978-2-87691-327-1).

- Martine Jolly, Merci M. Parmentier, ou La gloire de la pomme de terre en 200 recettes, Robert Laffont, 1985, 224 p. (ISBN 2-221-04653-6).

- Mme Mérigot, La Cuisinière républicaine, qui enseigne la manière simple d'accommoder les pommes de terre ; avec quelques avis sur les soins nécessaires pour les conserver Archived July 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Paris, Chez Mérigot jeune, 1794–1795, 42 p.

- C. Monteros, J. Jiménez, Gavilanes, La Magia de la Papa Nativa. Recetario Gastronómico, Quito, INIAP, 2006, 71 p.

- Patrick Pierre Sabatier, La pomme de terre, c'est aussi un produit diététique, Robert Laffont, 1993, 275 p. (ISBN 2-221-07631-1).

- Racines, tubercules, plantains et bananes dans la nutrition humaine, FAP, coll. « Nutrition », no 24, Rome, 1991 (ISBN 92-5-202862-5).

- Joël Robuchon et Patrick Sabatier, Le Meilleur et le Plus Simple de la pomme de terre, Robert Laffont, 1994, 250 p. (ISBN 2-253-08159-0).

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Encyclopédie méthodique. Arts et métiers mécaniques dédiés et présentés à Monsieur Le Noir, Conseiller d'État, ancien Lieutenant général de Police, t. VI, Panckoucke, Paris, 1789, p. 73, 77 and 83.

- ^ François Rozier and J. A. Mongez le jeune, « Observations sur la physique, sur l'histoire naturelle et sur les arts, avec des planches en taille-douce dédiées à Monseigneur le comte d'Artois », in Journal de physique, de chimie, d'histoire naturelle et des arts, t. IX, Paris, January 1782, p. 83.

- ^ Jean Ferniot and Joël Robuchon (preface), Chère pomme de terre, see bibliography, p. IX and 7.

- ^ Mamani, Mauricio (1985). El chuño: preparacion, uso, almaneciamento in La tecnología en el mundo andino, vol. 1 (in Spanish). UNAM. p. 235. ISBN 968-837-293-5.

- ^ Salaman, Redcliffe (1985). The History and Social Influence of the Potato. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-521-07783-4.

- ^ (es) Prentice Mori, Mika Malena et al., « Estudio del efecto de tocosh de papa como probiótico en el control del peso corporal y mayor crecimiento en ratas jovenes frente a cultivo de Lactobacillus acidophillus », on V Congreso mundial de medicina tradicional, Facultad de Medicina Humana – Universidad de San Martín de Porres (Lima), 2005

- ^ a b Salaman, Redcliffe (1985). The History and Social Influence of the Potato. Cambridge University Press. pp. 593–597. ISBN 0-521-07783-4.

- ^ Jean Boulaine and Jean-Paul Legros (1998). D'Olivier de Serres à René Dumont. Portraits d'agronomes (in French). TEC & DOC Lavoisier. p. 30. ISBN 2-7430-0289-1.

- ^ Garnier, André (1992). Pains et viennoiseries, recettes et techniques (in French). Lucerne: Dormonval. p. 9. ISBN 2-7372-2272-9.

- ^ ''Sur la Pomme de terre'', #28 of April 4, 1792, in ''La Feuille villageoise, adressée, chaque semaine, à tous les villages de la France pour les instruire des Lois, des Evénements, des Découvertes qui intéressent tout Citoyen'', 2nd year, 4th part, Desenne, Paris, 1792, 636p, p40-42

- ^ Honoré Lacombe de Prézel (1761). Dictionnaire du citoyen, ou abrégé historique, théorique et pratique du commerce (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Grangé. p. 35.

- ^ Diderot et d'Alembert (1781). Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (in French). Vol. XXXIV. Berne et Lausanne. pp. 679 and 680, 684 and 685.

- ^ Durand, Jean-Claude (1834). La Pomme de terre. Considérations sur les propriétés médicamenteuses, nutritives et chimiques de cette plante (in French). Lyon: Rusand. p. 895.

- ^ a b c Diderot et d'Alembert (1781). Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (in French). Vol. XXXIV. Berne et Lausanne. pp. 679, 680, 684, and 685.

- ^ A. and R. Draize (1980). À table chez une grand-mère gaumaise. Recueil de recettes de cuisine gaumaise, véritables et anciennes (in French). Vieux-Virton: Éd. de la Dryade. pp. 45, 53 and 59.

- ^ 'Journal d'agriculture, sciences, lettres et arts, rédigé par des membres de la société royale d'émulation de l'Ain'', Imp. De Milliet-Bottier, Bourg, 1847, 376p, p30.

- ^ a b Parmentier, Antoine (1773). Examen chymique des pommes de terre. Dans lequel on traite des parties constituantes du bled (in French). Paris: Didot. pp. 145, 225–227.

- ^ Dictionnaire technologique, ou nouveau dictionnaire universel des arts et métiers et de l'économie industrielle et commerciale (in French). Brussels: Lacrosse et cie. 1839. pp. 85–90.

- ^ Rolet, Antonin (1913). La Conservation des matières alimentaires dans les ménages, à la ferme et dans les coopératives agricoles. Les conserves de légumes, de viandes, des produits de la basse-cour et de la laiterie (in French). Paris: J.-B. Baillière et fils. pp. 109–110.

- ^ James N. BeMiller, Roy L. Whistler (2009). Starch: Chemistry and Technology. Food Science and Technology Series (3rd ed.). Academic Press. p. 512. ISBN 978-0-08-092655-1.

- ^ French: La facilité avec laquelle nos Pommes de terre ſe prêtent à toutes ſortes de ragoût m'a fait naitre l'idée d'en composer un repas, auquel j'invitai pluſieurs Amateurs ; & au riſque de paſſer pour être atteint de la manie des Pommes de terre, je vais terminer cet Examen par en faire la deſcription : c'étoit un dîné. On nous ſervit d'abord deux potages, l'un de purée de nos racines, l'autre d'un bouillon gras, dans lequel le pain de Pommes de terre mitonnoit aſſez bien ſans s'émietter ; il vint après une matelote suivie d'un plat à la ſauce blanche, puis d'un autre à la maître d'hôtel, & enfin un cinquième au roux. Le ſecond ſervice conſiſtoit en cinq autres plats non moins bons que les premiers ; d'abord un pâté, une friture, une ſalade, des beignets, & le gâteau économique dont j'ai donné la recette ; le reſte du repas n'étoit pas fort étendu, mais délicat & bon ; un fromage, un pot de confiture, une aſſiette de biſcuit, une autre de tartes, & enfin une brioche auſſi de Pommes de terre, compoſoient le déſert ; nous primes après cela le caffé, auſſi décrit plus haut. Il y avait deux ſortes de pain ; celui mêlé de pulpe de Pommes de terre & farine de froment, repréſentoit aſſez bien le pain mollet ; le ſecond, fait de pulpe de Pommes de terre, avec leur amidon, portoit le nom de pain de pâte ferme ; j'aurois deſiré que la fermentation m'eut mis à même de faire une boiſſon de nos racines, pour contenter pleinement mes convives, [227] & dire avec fondement : aimez-vous les Pommes de terre, on en a mis partout. Chacun fut gai ; & ſi les pommes de terre ſont aſſoupiſſantes, elles produisent ſur nous un effet tout contraire

- ^ Benjamin de Constant; et al. (1817). Mercure de France (in French). Vol. II. Paris. pp. 215–216.

- ^ Alfred Nettement, « Parmentier », in La Semaine des familles, December 6, 1862, included inLa Semaine des familles. Revue universelle. 1862–1865, Paris, 1863, 828 pages p. 147.

- ^ Jean Boulaine et Jean-Paul Legros (1998). D'Olivier de Serres à René Dumont. Portraits d'agronomes (in French). TEC & DOC Lavoisier. p. 30. ISBN 2-7430-0289-1.

- ^ Dumas, Alexandre (1873). Grand dictionnaire de cuisine (in French). Paris: Alphonse Lemerre.

- ^ Elmståhl, H Liljeberg (May 24, 2002). "Resistant starch content in a selection of starchy foods on the Swedish market". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 56 (6): 500–505. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601338. PMID 12032648. S2CID 43685093.

- ^ Patrick Pierre Sabatier (1993). La pomme de terre, c'est aussi un produit diététique (in French). Robert Laffont. p. 122. ISBN 2-221-07631-1.

- ^ Michel Martin, Jean-Michel Gravoueille (2001). Stockage et conservation de la pomme de terre (in French). ITCF. p. 21. ISBN 2-86492-462-5.

- ^ Thorez, Jean-Paul (2003). " La pomme de terre ", in L'Encyclopédie du potager (in French). Actes Sud. p. 687. ISBN 2-7427-4615-3.

- ^ Woolfe, Jennifer A.; Poats, Susan V. (1987). The Potato in the Human Diet. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-521-32669-9.

- ^ Salaman, Redcliffe N. (1985). The History and Social Influence of the Potato (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 0-521-31623-5.

- ^ Contamine, Anne-Céline (July 1, 2008). "Marchés de la pomme de terre dans l'Union européenne". Cahiers Agricultures (in French). 17 (4): 335–342. doi:10.1684/agr.2008.0220.

- ^ "Are Green Potatoes Dangerous to Eat? | Britannica".

- ^ Jennifer A. Woolfe (1987). The Potato in the Human Diet. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0-521-32669-9.

- ^ Derenne, Jean-Philippe (1999). La Cuisine vagabonde (in French). Paris: Fayard/Mazarine. pp. 347–348. ISBN 2-213-60378-2.