Postal voting in the United States

Postal voting in the United States, also referred to as mail-in voting or vote by mail,[4] is a form of absentee ballot in the United States. A ballot is mailed to the home of a registered voter, who fills it out and returns it by postal mail or drops it off in-person at a secure drop box or voting center. Postal voting reduces staff requirements at polling centers during an election. All-mail elections can save money,[5] while a mix of voting options can cost more.[6] In some states, ballots may be sent by the Postal Service without prepayment of postage.[7]

Research shows that the availability of postal voting increases voter turnout.[8][9][10] It has been argued that postal voting has a greater risk of fraud than in-person voting, though known instances of such fraud are very rare.[11] One database found absentee-ballot fraud to be the most prevalent type of election fraud (at 24%) with 491 reported prosecutions between 2000 and 2012 out of billions of votes were cast.[12] Experts are more concerned with legally-cast mail-in ballots discarded on technicalities than with voter fraud.[13][14][15][16][17]

As of 2022, eight states – California, Colorado, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Vermont, and Washington – allow all elections to be conducted by mail. Five of these states – Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington – hold elections "almost entirely by mail."[18] Postal voting is an option in 33 states and the District of Columbia. Other states allow postal voting only in certain circumstances, though the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 prompted further discussion about relaxing some of those restrictions. After repeatedly asserting that mail-in voting would result in widespread fraud in the run up to the 2020 United States presidential election, President Donald Trump indicated he would block funding for the Postal Service necessary to ensure that postal votes would be processed securely[19] and on time.[20]

In September 2020, CNN obtained a Homeland Security Department intelligence bulletin asserting "Russia is likely to continue amplifying criticisms of vote-by-mail and shifting voting processes amidst the COVID-19 pandemic to undermine public trust in the electoral process."[21] Motivated by false claims of widespread voter fraud in the 2020 election, Republican lawmakers initiated a push to roll back access to postal voting.[22]

History

[edit]Absentee voting in the United States first emerged in colonial America, when soldiers serving in the Continental Army and individuals who lived in homes that were "vulnerable to Indian attack" could utilize absentee voting.[23][24] Absentee ballots were first used on a large scale for the military during the American Civil War.[25][26] Early absentee voting laws restricted the practice to members of the armed services.[27] The first allowance for civilian absentee voting was in Vermont in 1896.[27] By 1938, 42 states allowed absentee voting for civilians.[27] Nearly 2% of voters in the 1936 election voted through absentee ballots.[27] Starting in the 1970s, more states began to offer no-excuse absentee voting, allowing voters the ability to vote absentee without needing an excuse.

The share of absentee voters has increased over time.[27] Historically, one particularly prominent group who voted through absentee ballots were federal employees in Washington, D.C.[27]

Process

[edit]

Postal voting was initially intended for voters unable to go to the polling place on Election Day. Some states now allow mail-in ballots for convenience, but some still refer to them as absentee ballots.[28] Some states that require an approved excuse to vote by mail allow voters with permanent disabilities apply for permanent absentee voter status, and some others allow all citizens to apply for permanent status so they will automatically receive an absentee ballot for each election.[29] In others, a voter must apply for an absentee ballot before each election.

Ballots or applications for postal ballots are sent out before the election date, by a margin that depends on state law. In some states, a voter's pamphlet is also distributed. The election office prints a unique barcode on the return envelope provided for each ballot, so processing of each envelope can be tracked, sometimes publicly,[30] and corresponding signature files can be loaded quickly to check the voter's signature on the envelope when it returns.[31][32][33][34] Voters who lose the return envelope can still vote by obtaining another envelope from election officials,[35] or in some jurisdictions by using a plain envelope.[36]

To vote by mail, an individual marks the ballot for their choice of the candidates (or writes in their name), places it in the provided mailing envelope, seals it and signs and dates the back of the mailing envelope. Some jurisdictions use one envelope or privacy sleeve inside an outer envelope, for privacy. The envelope containing the ballot is then either mailed, or dropped off at a local ballot collection center.[37]

The deadline is determined by state law.[38] In some jurisdictions, postmarks are not counted, and ballots must be received by a certain time on election day. In other jurisdictions, a ballot must have a postmark on or before the day of the election and be received prior to the date of certification. Many vote-by-mail jurisdictions enlist the help of volunteers to take ballots in walk-up drop off booths or drive-up quick drop locations.[37] The Help America Vote Act requires some polling options, often at central election headquarters, with voting machines designed for disabled people.

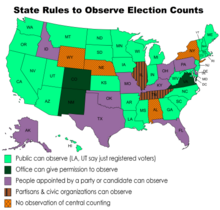

It is sometimes inaccurately claimed that absentee ballots are not counted unless the race is close; in fact, all valid absentee ballots are counted in every election and jurisdiction, even if they will not affect the outcome of an election.[39][40][41] Counting of absentee ballots is usually done centrally. States vary in the rules about who may observe the counting. In New Hampshire, absentee ballots are sorted and transported to polling places for counting.

In the 2016 US Presidential election, approximately 33 million ballots were cast by postal vote, about a quarter of all ballots cast.[42] Some jurisdictions used only vote-by-mail and others absentee votes.

In April 2020, during lockdowns for the coronavirus pandemic, an NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll found that 58% of American voters would favor nationwide election reform to allow everyone to vote by mail, and another 9% (total 67%) favor allowing it this year because of COVID-19.[43] Pew Research found at the same time that 49% of Republicans and 87% of Democrats supported this measure.[44]

Pre-processing of mail-in ballots

[edit]

One variable with a significant impact on both the speed of election reporting and public perception of election processes involves when processing of mail-in ballots is allowed to begin.

Forty-three states begin preparing mail or absentee ballots for counting before Election Day. This practice of pre-processing gives election officials more time to detect and address errors or irregularities in the ballots and to notify voters about ballots in need of correction (called curing the ballot).

States that do not allow pre-processing—including Pennsylvania and Wisconsin—require officials to wait until Election Day to begin mail-in ballot verification and curing. This often delays the release of election results until several days after polls close.[45]

The 2020 election in Pennsylvania illustrated the potential impact of the delay. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the state received 2.6 million mail-in ballots, a tenfold increase compared to past elections. None of these by law could be processed until 7 a.m. on Election Day. Three times as many Democrats as Republicans had made use of the mail-in option.[46] This combined with the required delay in processing to produce a switch from a Republican lead to a Democratic lead several days after the election as mail-in ballots were completed—which in turn fueled conspiracy theories falsely claiming vote tampering by officials.[47]

Voting from abroad (UOCAVA)

[edit]In 2018, 350,000 ballots came through procedures of the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA), from military and merchant marine voters stationed inside or outside the United States, and other citizens living outside the United States.[48] In 1986 Congress enacted UOCAVA, which requires that the states and territories allow United States citizens residing outside the United States, as well as members of the United States Uniformed Services and merchant marine, and their family members, inside or outside the United States, to register at their last residence in the US, and vote absentee in elections for federal offices.[49] Most states and territories also let these citizens vote in state and local elections,[50] and most states let citizens who have never lived in the US vote at their parents' last address.[51]

Though many states had pre-existing statutes in place, UOCAVA made it mandatory and nationally uniform. Voters eligible for UOCAVA who do not receive an absentee ballot from their state in time to vote, may use the Federal Write-in Absentee Ballot. The voter's signature goes on an information sheet enclosed with this ballot, not on the envelope.[52] It requires following state requirements for witnesses, but not for notaries. Almost half the states require ballots to be returned by mail. Other states allow mail along with some combination of fax, or email; four states allow a web portal.[53] West Virginia experimented with use of smart phones, but this is no longer available.[54]

In states

[edit]The National Conference of State Legislatures has many tables showing rules about postal voting in every state.[28]

Texas (voting from orbit)

[edit]In 1996, astronaut John Blaha was not able to vote in the November 1996 election, because his mission on Mir began before ballots were finalized, and lasted beyond Election Day.[55] As a result, in 1997, Texas amended its election statutes to permit voting from outer space.[55][56][57] The process extends traditional postal voting: the ballot is postal-mailed to a designated mailbox maintained by NASA, which sends it by encrypted electronic mail to the astronaut. After the astronaut completes the ballot, it is sent to the applicable Texas county clerk, who transcribes it to a paper ballot.[58] The clerk is the only individual other than the voter who knows the contents of the submitted ballot.[58] The first person to vote from space was astronaut David Wolf, who in 1997 voted in a local Texas election under the new law.[58]

All vote-by-mail

[edit]As of 2022, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Vermont, and Washington allow all elections to be conducted by mail. In many other states there are counties or certain small elections where everyone votes by mail.[28][59] California mailed every voter a ballot before the November 2020 election; California voters still kept the option to vote in-person.[60][61]

California

[edit]In 2016, California passed SB 450, which authorizes a roll-out of vote by mail across the state, at county discretion.[62] The state publishes postal voting rates, rising from 3% in 1962 to 72% in 2020.[63] For the 2018 elections, 14 counties were authorized to vote by mail and five ultimately did so: Madera, Napa, Nevada, Sacramento, and San Mateo. In each of those five counties, voter turnout was higher than the average turnout for the state.[64] For 2020, all counties will be authorized to do so, and as of April 8, 2020 the following ten additional counties have opted in: Amador, Butte, Calaveras, El Dorado, Fresno, Los Angeles, Mariposa, Orange, Santa Clara, and Tuolumne.[65]

As of 2022, California mails every registered voter a ballot before the elections, but there is still the option to vote in-person.[66]

Colorado

[edit]In 2013, Colorado began holding all elections by mail.[67] A Pantheon Analytics study of the 2014 election showed a significant uptick in voter participation from what would have normally been "low propensity" voters.[68] A PEW Charitable Trust study of the same election showed significant cost savings.[5]

Hawaii

[edit]Hawaii instituted All-Vote-by-Mail for all elections beginning with its primary in May 2020.[69]

Kansas

[edit]Kansas conducted its Democratic primary in May 2020 entirely by mail.[70]

Nevada

[edit]Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak (D) signed legislation authorizing mail-in-voting for every registered voter in the state on August 3, 2020.[71] (Donald Trump threatened to sue,[72] although Trump endorsed mail-in-voting in Republican-controlled Florida.[73][74]) That law was only temporary, applying only to the 2020 election. On June 2, 2021, Governor Sisolak signed a law making all vote-by-mail permanent, although voters can opt out of getting ballots by mail.[75]

New Jersey

[edit]New Jersey conducted a primarily vote by mail election for the primary in July 2020 albeit with a limited number of polling stations open for those who would vote provisionally as well as voters with disabilities.[76]

Oregon

[edit]

In 1998, voters in Oregon passed an initiative requiring that all elections be conducted by mail. Voters may also drop their ballots off at a county designated official drop site. Oregon has since reduced the cost of elections, and the time available to tally votes has increased. Initially, Oregon required receipt of votes by 8:00 pm local time on election day. But starting with the general election in 2020, ballots needed to be postmarked by Election Day. Also starting then, pre-paid postage envelopes were included with the ballots. Voter turnout in Oregon is among the highest in the United States.[77]

Utah

[edit]In 2014, Utah started allowing each county to make their own decision regarding whether to go to all mailed-out ballots. In the 2016 general election, 21 of 29 counties did so. That rose to 27 of 29 counties in 2018, covering over 98% of their electorate, with all counties doing so in 2020.[78][28] A Pantheon Analytics study of Utah's 2016 general election showed a 5–7% point higher turnout in the counties using vote by mail than those with traditional polling places, with even higher differences (~10% points) among younger voters.

Vermont

[edit]On May 18, 2021, the Vermont legislature passed a bill requiring general elections to be all vote-by-mail.[79] Vermont Governor Phil Scott signed that bill on June 7, 2021, and asked the legislature to expand all vote-by-mail to primary elections too.[80]

Washington

[edit]In 2011, the Washington legislature passed a law requiring all counties to conduct vote-by-mail elections.[81] Local governments in Washington had the option to do so since 1987, and statewide elections had permitted it since 1993.[82] By 2009, 38 of the state's 39 counties (all except Pierce County) had conducted all elections by mail.[83] Pierce County joined the rest of the state in all-mail balloting by 2014.[84] In Washington, ballots must be postmarked by election day, which helps to ensure all voters' votes are counted; ballot counting takes several days after election day to receive and process ballots.[83] Beginning in 2018 postage is prepaid so voters do not have to use a stamp.[85]

Local jurisdictions

[edit]Various local jurisdictions now have all vote-by-mail, or run pilot programs. 31 of 53 counties in North Dakota now vote by mail,[86] as do over 1000 precincts in Minnesota (those with fewer than 400 registered voters). In 2018, pilot programs in Anchorage, Alaska exceeded previous turnout records[87] and Garden County, Nebraska saw higher turnout versus the state average.[88] Rockville, Maryland piloted vote-by-mail in 2019.[89] In 2018, Connecticut's Governor issued Executive Order 64, directing a study of a possible move to vote by mail.[90]

No-excuse postal voting

[edit]A study by the Center for Election Innovation & Research documented a steady increase in no-excuse postal voting (i.e., voters may vote by mail without an eligible reason) since the 2000 general election:

- In 2000, 21 states allowed no-excuse postal voting for the general election

- In 2004, 24 states

- In 2008, 28 states

- In 2012, 30 states and Washington, DC

- In 2016, 31 states and Washington, DC

- In 2020, 45 states and Washington, DC (sudden increase due in part to emergency measures during the COVID-19 pandemic)

- In 2024, 36 states and Washington, DC

As of September 2024, 14 states allow postal voting but require an eligible reason.[91]

In 2018, Michigan passed Proposal 3, a state constitutional amendment legalizing "no-excuse" postal voting and other election reforms. In 2020 three more states joined the majority of states which already allowed "no excuse" postal voting: Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Virginia.[28]

On May 31, 2021, the Illinois legislature passed a bill that expanded curbside voting and establishes a permanent postal voting system, and it creates a permanent voter list. It was signed by Illinois Governor J. B. Pritzker on June 18, 2021.[92] In June 2023, the Connecticut legislature sent a ballot measure to the voters which, if passed in 2024, would amend the state constitution to allow no-excuse postal voting.

In September 2023, the New York Legislature passed a bill legalizing no-excuse absentee early voting up to nine days before an election or primary, which was signed into law by Governor Kathy Hochul.[3]

Table: No-excuse postal voting

[edit]- Links below are "Elections in LOCATION" links.

| State or federal district | Implemented statewide | All-mail elections |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | ||

| 1978 | Yes (since 2022)[93] | |

| Yes (since 2013) | ||

| 2001 | ||

| 2006 | ||

| 1993 | Yes (since 2019) | |

| 1972 | ||

| 2006 | ||

| 1990 | ||

| 2000 | ||

| 2022 | ||

| 2018 | ||

| 2014 | ||

| 1997 | ||

| Yes (since 2020) | ||

| 2006 | ||

| 1993 | ||

| 2024[3] | ||

| 2002 | ||

| 2005 | ||

| 1998 | Yes (since 1998) | |

| 2020 | ||

| 2020 | ||

| 2003 | ||

| 2013 | Yes (since 2020) | |

| 1991 | general elections only (since 2021) | |

| 2020 | ||

| 1974 | Yes (since 2011) | |

| 2023 | Yes (since 2023)[94][2] | |

| 2001 | ||

| 1991 |

Table: Permanent absentee voting lists

[edit]Info in table below is from the National Conference of State Legislatures: "Some states permit voters to join a permanent absentee/mail ballot voting list, also known as a 'single sign-on' list. Voters who request to be on this list automatically receive an absentee/mail ballot for each election. This option may be offered to all voters, or to a limited number of voters based on certain criteria. ... An additional six states [Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Missouri, and Alaska] not included on the table automatically send absentee/mail ballot applications to voters on a permanent list. This differs from the states in the table below since voters must return the application before receiving an absentee/mail ballot."[29]

- Links below are "Elections in LOCATION" links.

| State | Any voter | Permanent disabilities | Senior voters (65 and older) |

|---|---|---|---|

Ala. Code § 17-11-3.1 |

* | ||

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §16-544(A) |

* | ||

Conn. Gen. Stat. 9-140e |

* | ||

Del. Code Ann. Tit. 15, §5503(k) |

* | ||

D.C. Mun. Regs. Tit. 3, § 720.4 |

* | ||

Kan. Stat. Ann. §25-1122(h) |

* | ||

Louisiana Secretary of State Disability Program |

* | * | |

21-A ME Rev Stat § 753-A (effective Nov. 1, 2023) |

* | * | |

Md. Code, Elec. Law § 9-311.1 |

* | ||

Miss. Code Ann. § 23-15-629 |

* | ||

Mont. Code Ann. §13-13-212(3) |

* | ||

N.J. Stat. §19:63-3(e) |

* | ||

N.Y. Election Law §8-400 |

* | ||

T. C. A. § 2-6-201 |

* | ||

VA Code 24.2-703.1 |

* | ||

W. Va. Code §3-3-2b |

* | ||

Wis. Stat. § 6.86(2)(a) |

* | * |

Turnout

[edit]Insofar as postal voting makes the act of voting easier, it may facilitate a campaign's get out the vote efforts. Campaigns can also target potential voters more efficiently by skipping those whose ballots have already been processed by the elections office. Conversely, face-to-face canvassing has been found to be less effective with postal voting.[95]

In 2016, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report outlining turnout improvements seen in vote by mail elections.[96]

Researchers in 2020 have found that in elections with all-mail voting, overall turnout increases. This increase is particularly pronounced among groups that typically have low turnout rates, such as young people and people of color. For instance, in Colorado they found overall turnout rose 9 percentage points, while it rose 16 percentage points among young people, 13 among African-Americans, 11 among Asian-Americans, 10 among Latinos, blue-collar workers, those without a high school diploma, and those with less than $10,000 of wealth.[8]

Reliability of postal ballots

[edit]Rejection statistics

[edit]

As of 2020, about 1% of postal ballots were rejected (compared to .01% in-person where election workers can help verify and assist the voter).[97] For the states that reported a reason in 2016, common reasons were:[16]

- Non-matching signature (.28%)

- Ballot missed deadline (.23%)

- No signature (.20%)

- No witness signature (.03%)

- Voter deceased (.015%)

- Voted in person (.013%)

- First-time voter without proper identification (.011%)

Past problems

[edit]Richard Hasen, a professor at University of California, Irvine School of Law said, "problems are extremely rare in the five states that rely primarily on vote-by-mail."[98] Postal ballots have been the source of "most significant vote-counting disputes in recent decades" according to Edward Foley, director of the Election Law program at Ohio State University.[99] Among the billions of votes from 2000 to 2012, there were 491 known cases of absentee ballot fraud.[100][101][11] Justin Levitt, a law professor at Loyola Marymount University does not have statistics on postal ballot fraud, but said "I do collect anecdotal reports ... misconduct in the mail voting process is meaningfully more prevalent than misconduct in the process of voting in person ... Misconduct still amounts to only a tiny fraction of the ballots cast by mail."[98] Lonna Atkeson, an expert in election administration, said about mail-in voting fraud, "It's really hard to find ... The fact is, we really don't know how much fraud there is ... There aren't millions of fraudulent votes, but there are some."[98]

Advantages

[edit]- Auditable paper mail-in ballots are potentially safer than paperless voting systems[102]

Issues

[edit]Receiving a ballot

[edit]- Voter does not receive mailed ballot, because it does not arrive at the address in time, or someone else takes it[17][103][104]

- Voter's request for postal ballot is lost or not received or processed in time, in states that require one, thus the voter must vote in person or not vote (for example over 9,000 properly requested ballots were not sent in Wisconsin in 2020)[17]

- Voter's request for postal ballot is altered or forged[105][106][107]

- In states that mail ballots to registered voters without request, some voters have died or moved, and any ballots not returned by the post office can get into the wrong hands[108]

- Election office sends voters the wrong instructions[109] or a ballot with someone else's name on it,[110] or wrong ballot, when offices on the ballot differ by party or district.[111]

- Voter misplaces ballot, so must vote with provisional ballot, and someone else may find and vote the original postal ballot, leading to rejection of the provisional ballot.[112][103]

Filling out a ballot

[edit]- Voter is pressured to vote a certain way by family, caregiver, or other, or provide the blank ballot to someone[113][114]

- Voters may be paid to vote a certain way[115]

Casting a ballot

[edit]- Someone collects many ballots[116] and does not deliver the ones from neighborhoods likely to vote against the collector's candidates[117]

- Someone collects many ballots, opens envelopes, and marks votes; if voter has already voted, fraudster can mark extra votes on same contests, to invalidate ballot[118]

- Mail can be stolen from postal service[119][120]

- Staff can leave key in drop box.[121]

- Envelope printer prints erroneous tracking code on return envelope, so it may be processed inaccurately or rejected.[122][123]

- Election office receives the ballot late (114,000 ballots in 2018);[48][124][125] in a Philadelphia experiment, most ballots were misplaced by the postal service, and even after they were found, 21% took more than 4 days to arrive and 3% took more than a week[126]

- Staff who open envelopes falsify or ignore ballots[127][128]

- Compilation of votes omits postal ballots[129]

Signature issues

[edit]- Voter's signature on envelope is missing (55,000 in 2018) or does not match signature on file (67,000), so either there is widespread fraud being prevented by signature reviews, or if these submissions were not fraudulent, then valid ballots are being rejected[48][14]

- Forged signature on envelope is accepted as close enough to signature on file, so invalid ballots are accepted[14]

- Signature rejection rates vary by race, county and state, ranging from none to 20% rejected[16][15]

Signature verification process

[edit]Most states check signatures to attempt to prevent forged paper ballots. Signature mismatches were the most common reason for rejecting postal ballots in 2016[16] and the second most common, after late arrival, in 2018.[48] While many states accept in-person votes without needing identification, most require some verification on postal ballots.[130] As of 2024, 31 states conduct signature verification on returned absentee or mail-in ballots. Nine states do not conduct signature verification, but require the signature of either a witness, two witnesses, or a notary. Ten states and Washington, D.C. neither conduct signature verification nor require a witness signature.[131]

The first step after receiving mailed ballots is to compare the voter's signature on the outside of the envelope with one or more signatures on file in the election office. Smaller jurisdictions have temporary staff compare signatures. Larger jurisdictions use computers to scan envelopes, quickly decide if the signature matches well enough, and set aside non-matches in a separate bin. Temporary staff then double-check the rejections, and in some places check the accepted envelopes too.[14]

Error rates of computerized signature reviews are not published. The best academic researchers have 10-14% error rates.[132] Algorithms:

look for a certain number of points of similarity between the compared signatures ... a wide range of algorithms and standards, each particular to that machine's manufacturer, are used to verify signatures. In addition, counties have discretion in managing the settings and implementing manufacturers' guidelines ... there are no statewide standards for automatic signature verification ... most counties do not have a publicly available, written explanation of the signature verification criteria and processes they use.[14]

Handwriting experts say "it is extremely difficult for anyone to be able to figure out if a signature or other very limited writing sample has been forged,"[133] In manual signature reviews, "election officials with little or no training in verifying a person's signature are tasked with doing just that ... it's unlikely that only one or two samples will show the spectrum of a person's normal variations ..."[133] Colorado's guide for manual verification is recommended by the federal government.[134] Colorado accepts any signature that matches with respect to cursive v. printed, flowing v. slow and deliberate, overall spacing, size, proportions, slanted v. straight, spelling and punctuation. When signatures do not match on these items, staff still accept them if staff can think of a reasonable explanation for differences.[135] In a California study, most counties, when they manually reviewed ballot signatures, had "a basic presumption in favor of counting each ballot."[14] California extended this standard in 2020 regulations, "begin with the basic presumption that the signature on the petition or ballot envelope is the voter's signature ... only be rejected if two different elections officials unanimously find beyond a reasonable doubt that the signature differs in multiple, significant, and obvious respects from all signatures in the voter's registration record."[136] Texas officials must use their "best judgment" without training.[137] Published examples show very different signatures coming from the same person.[137]

In 16 states, when election offices reject signatures, they notify the voters so they can mail another signature, which may be just as hard to check, or they can come to the office and vouch for the envelope, usually in less than a week; the other 36 states have no process to cure discrepancies.[138] Notification by US mail results in more cures than email or telephone notice.[14] In the Florida 2020 general election, 73% of the 47,000 initially rejected ballots were cured,[139] and in the 2022 Vermont primary, 61% of 809 were cured.[140]

Rejected envelopes, with ballots still unseen in them, are stored in case of future challenges. Accepted envelopes are opened and separated from the envelopes in a way that no one sees the external name and the ballot choices. The Election Assistance Commission says machines can help, but this step requires the most space of any step, especially when workers have to be 6 feet apart.[141]

Unequal signature rejection rates

[edit]

The highest error rates in signature verification are found with lay people, higher than for computers, which in turn make more errors than experts.[142] Researchers have published error rates for computerized signature verification. They compare different systems on a common database of true and false signatures. The best system falsely rejects 10% of true signatures, while it accepts 10% of forgeries. Another system has error rates on both of 14%, and the third-best has error rates of 17%.[132][143] It is possible to be less stringent and reject fewer true signatures, at the cost of also rejecting fewer forgeries, which means erroneously accepting more forgeries.[144] Vendors of automated signature verification claim accuracy, and do not publish their error rates.[145][146][147][148]

Voters with short names are at a disadvantage, since even experts make more mistakes on signatures with fewer "turning points and intersections."[149]

The National Vote at Home Institute reports that 17 states do not mandate a signature verification process.[150]

In the November 2016 general election, rejections ranged from none in Alabama and Puerto Rico, to 6% of ballots returned in Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky and New York.[16][151] In 2020 special elections in New Jersey, 10% of postal ballots were rejected, much higher than the 3% rejections in the 2018 general election in New Jersey. The rise was largely attributed to inexperience of many voters using postal ballots for the first time, though some elections have resulted in charges regarding voter fraud. One such race was the Paterson municipal election, where 19% of ballots cast were disqualified. Approximately 800 of the more than 3190 votes disqualified were related to the various voter fraud allegations.[152][153][154] Where reasons for rejection were known, in 2018, 114,000 ballots arrived late, 67,000 failed signature verification, 55,000 lacked voter signatures, and 11,000 lacked witness signatures in states that require them.[48]

Rejection rates are higher for ballots that claim to come from young or minority voters. In the 2020 primary[155] and 2016 general[15] elections, Florida officials rejected 4% of postal ballots that claimed to come from voters aged 18–25. In the 2018 general election they rejected 5%.[156] In Florida over age 60 or 65, rejections were only one percent in 2020, two thirds of a percent in 2018 and half a percent in 2016. However over age 90, rejection rates were above average, though not as high as under age 25.[156] Rejections were 2% for ballots claiming to come from Florida non-white voters, and 1% from white voters in all three years.[155][156][15] In the 2018 Florida election, 4% of postal ballots from military voters stationed inside the United States were rejected.[156] Florida voters are not allowed to cure signature problems if these are discovered after election day.[138]

Florida rejection rates in 2016 varied by county, ranging from none to 4%, and up to 5% for ballots that claimed to come from blacks or Hispanics in some counties. Two counties with large universities rejected 9% of 18-21-year-olds: Alachua and Orange, while Pinellas, which also has large universities, rejected 0.2% of this age range.[15]

In Georgia's 2018 general election, most counties rejected higher fractions of ballots claiming to come from black or Hispanic voters than from white voters. The highest rejection rates for ballots that claimed to come from black voters were in Polk 17%, Taylor and Clay 16%, Putnam, and Warren 14%, Atkinson and Candler 13%, McIntosh 12%, and Glynn 10%. For Hispanics, Thomas and Putnam counties rejected 20%, Bulloch 14%, Barlow 12%, Glynn 11%, Decatur 10%. The highest rates for whites were Pickens 13%, Coffee and Polk 10%. Researchers also found higher rejection rates for women, which they hypothesized could relate to name changes not updated at the voter registration office,[157][158] though issues with hyphenated last names can also cause signature rejections.[159] Bias in computer verification depends on the set of signatures used for training the computer, and bias in manual review depends on whether the temporary staff recognize names as non-white.[citation needed]

Many voter registrations, especially for younger voters, come from driver's license applications, where the signature is done on an electronic signature pad. People move their hands differently when signing on paper and on electronic pads. Further the pads used have low resolution, so distinctive elements of paper signatures on the ballot envelopes, are blurred or omitted in the electronic signatures used for comparison.[14] Signatures also have more variation, and therefore are harder to verify, when they come from people who rarely use Roman characters, such as some Asian-Americans.[14] Election officials find that a decline in cursive writing leads to young voters more often printing their names in signature blocks; a California official said she "cannot compare a printed name to a signature."[14]

This can be a difficult process for the actual workers that reject signatures. Attorney Raul Macias has said, "Staff are under-trained, they're under-resourced, and they'll be under tremendous pressure to get results quickly and they're moving through thousands or millions of signatures." While 22 states allow the "curing" of a ballot signature, 28 do not.[160]

Recommendations for signature verification

[edit]The Election Assistance Commission says computers should be set to accept only nearly perfect signature matches, and humans should doublecheck a sample, but they do not discuss acceptable error rates or sample sizes.[134]

The Election Assistance Commission says the first human check of a signature rejected by machines will average 30 seconds, and a sample of decisions to accept should be checked. They recommend all rejections should be checked by bipartisan teams (6 feet apart[141]) who will average 3 minutes for the final decision to reject, which means 6 minutes of staff time, plus supervision time. The commission also discusses the challenges of moving large numbers of envelopes without mixups from receipt, to machines, and various steps of verification, rejection, and voter notification to cure mismatches, as well as counting and logging the number of ballots at every step. They mention the extra security needed when voters send copies of identity documents to cure their signature rejection.[134]

The Election Assistance Commission notes that signatures over ten years old are another problem and recommends Hawaii's practice of inviting every voter to send a new signature.[134] California researchers recommended that the public needs easy access to see the signature on file before mailing in ballots, to further maximize matches.[14]

The National Vote at Home Institute recommends state-wide or regional centers for signature verification to increase transparency. and reduce the insider risks of temporary local staff,[161] though the Election Assistance Commission notes that shared equipment may not be consistent with local chain of custody requirements, and that public bidding may take months.[141]

Security printing

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (September 2024) |

This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (September 2024) |

Some states say they print postal ballots on special paper to prevent forgeries.[162][163] California assigns a tinted watermark to the ballots for each election,[164] which is created by printing an image with a screen rather than density variations.[165] Special papers, microprinting, magnetic ink and other measures are common to protect currency, bank checks and stamps. Election officials do not say that envelopes have these features, nor that they review ballots based on these methods,[48][16] though the Labor Department reviews paper when considering if union election ballots are forged.[166]

The largest US vendor of election scanners required use of its own paper as of 2015,[167] and "highly recommended" it as of 2019.[168] The paper has specified weight, thickness, reflectivity for compatibility with scanners, but the scanner does not measure these to detect forgeries. The company says colored paper may not be used. Colors may be printed in areas away from the voting marks, but they are scanned as either black or white, no gray.[168]

States print bar codes on return envelopes to identify the voter (coding a serial number for each envelope mailed),[169] so a forger would need to access the coding system in order to forge bar codes.[163] California lets voters write votes "in a letter or note" on any paper, and enclose as many such notes in a vote by mail envelope as will fit, with a signature for each on the outside. Only one bar code on the envelope is needed.[170]

Ballot printing is centralized. For example, California has nine authorized ballot printers.[171] Maryland uses one ballot printer state-wide.[172] One company, Runbeck, printed 36 million ballots for 214 counties in 11 states for the November 2020 election, of which about half were postal ballots.[173] Runbeck did not use watermarks or tracking marks in the paper, at least in Maricopa County which has over 60% of Arizona's voters.[174] A California company prints 35 million ballots for 46 counties.[175] Another company serves many counties in Ohio and Pennsylvania.[176]

Other challenges

[edit]Postal voting depends on the viability of the postal service. As of early 2020, the U.S. Postal Service has "a negative net worth of $65 billion and an additional $140 billion in unfunded liabilities." This financial crisis has become more pressing amidst the coronavirus pandemic, as the $2 trillion economic stimulus package did not include money for the postal service.[177]

In the case of all-postal voting, or a high proportion of postal votes, there cannot be traditional "Election Night" news coverage in which the results are delivered within hours after polls close, as it takes several days to deliver and count ballots. As a result, it may require several days beyond the mail-in deadline before results can be publicized.[178]

Blue shift

[edit]Blue shift is an observed phenomenon under which in-person votes overstate the true final percent of votes for the Republican Party (whose color is red), while provisional (and mail-in) votes, which are counted later, overstate the true final percent of votes for the Democratic Party (whose color is blue).[179] This means election day results can initially show a large Republican lead, or "red mirage", but mail-in ballots later demonstrate a Democratic victory. This can also happen in the opposite direction, when there is a "blue mirage", or early lead by Democrats, followed by a red shift back to Republicans.[180] This can lead observers to call into question the election legitimacy, when in fact, the election results are legitimate.[181] Blue shift occurs because young voters, low-income voters, and voters who move often, are likely to vote by mail and are likely to lean Democratic.[182]

The phenomenon was first identified by Edward Foley of Ohio State University in 2013.[182] He found that Democratic candidates are significantly more likely to gain votes during the canvass period, which are the votes counted after election night.[183] This asymmetry did not always exist, as in the 20th century, as recently as the 1996 United States presidential election, Republicans and Democrats were both able to cut their opponents' lead during the canvass period. Foley conjectured that the 2002 passage of the Help America Vote Act accelerated the pronounced asymmetry of the blue shift phenomenon, because it required states to allow provisional ballots to be cast.[183] He later found that the variation in the size of the blue shift is positively associated with the number of provisional ballots and the Democratic partisanship of the state in question.[184] The growth in the persistent blue-shifted overtime vote began with the 2004 United States presidential election.[184]

Alternatives

[edit]An increasing number of states in the US now allow drive-thru voting. In the process voters leave their absentee ballots in a drop box at designated locations. Some locations allow drop-off voting 24/7.[185]

Many states provide voters with multiple ways to return their ballot: by mail, via in person secure drop boxes, and at voting centers where they can get questions answered, replacement ballots, etc.[186] Oregon now has 300 drop boxes across the state in the weeks leading up to each election, and more voters now cast their ballot in person than by return mail.[187] The term "vote at home" is starting to replace "vote by mail" for that reason.[188] California's roll-out of vote-by-mail is incorporating voting centers as a key part of their effort.[187] Anchorage's successful pilot included many drop boxes and some voting centers.[187]

Expansion in 2020 election

[edit]In 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant increase in postal ballots was expected. The National Vote at Home Institute, which advocates postal ballots and is led by former Denver elections director Amber McReynolds, analyzed all states and found that 32 states "are missing major pieces of policy or best practices that ensure a secure mail ballot process"[189][150] including 15 states which lack steps to verify voters' addresses, 17 which do not mandate a signature verification process, and 30 do not have adequate options to cure defects in voter signatures.[150] In many systems voters have no way to remedy disqualifications due to signature mismatches.[138]

While members of Congress pushed to expand absentee voting and the CDC and other public health experts advised postal voting as a form of voting which minimizes in-person contact, President Donald Trump claimed that expansion of absentee voting would lead to "levels of voting that, if you ever agreed to it, you'd never have a Republican elected in this country again."[190] In May 2020, Trump began to claim that postal voting was highly vulnerable to fraud.[191] Fact checkers said that there is no evidence of substantial fraud associated with mail voting.[98][192] In July 2020, Trump suggested postponing the 2020 presidential election based on his unsubstantiated claims about extensive postal voting fraud.[193][194][195][196] The new, Trump-appointed administration of the United States Postal Service made changes which resulted in slower delivery of mail. Donald Trump openly stated that he opposes funding USPS because of mail-in voting.[197] In September 2020, a federal judge issued an injunction against the recent USPS actions, ruling that Trump and DeJoy were "involved in a politically motivated attack on the efficiency of the Postal Service", adding that the 14 states requesting the injunction "demonstrated that this attack on the Postal Service is likely to irreparably harm the states' ability to administer the 2020 general election".[198]

The USPS warned that it could not guarantee that all ballots cast by mail in the 2020 election would arrive in time to be counted.[199] For this reason, election experts advocated that postal ballots be mailed weeks in advance of election day.[200][verification needed] A March 2021 report from the Postal Service's inspector general found that the vast majority of mail-in ballots and registration materials in the 2020 election were delivered to the relevant authorities on time.[201][202] The Postal Service handled approximately 135 million pieces of election-related mail between September 1 and November 3, delivering 97.9% of ballots from voters to election officials within three days, and 99.89% of ballots within seven days.[201][203]

In several court cases in 2020, Republicans in national and state legislatures have pushed to restrict access or place more stringent limitations upon postal voting while Democrats have pushed to expand it or lift restrictions.[204][205][206]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Absentee/mail-in voting. Ballotpedia. Select a state in the right sidebar menu for detailed info.

- ^ a b c Request a Mail Ballot. District of Columbia Board of Elections.

- ^ a b c d Democracy Maps. Availability of No-Excuse Absentee Voting. MAP (Movement Advancement Project).

- ^ "Vote from Home, Save Your Country". Washington Monthly. January 10, 2016. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ a b "Colorado Voting Reforms: Early Results". pewtrusts.org. March 22, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Pre-Election Day Voting: Just the FAQs, Ma'am" (PDF). The Canvass. March 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "USPS DMM 703.8". USPS. January 1, 2010. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- ^ a b Hill, Charlotte; Grumbach, Jacob; Bonica, Adam; Jefferson, Hakeem (May 4, 2020). "We Should Never Have to Vote in Person Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ Wines, Michael (May 25, 2020). "Which Party Would Benefit Most From Voting by Mail? It's Complicated". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Daniel M.; Wu, Jennifer A.; Yoder, Jesse; Hall, Andrew B. (June 9, 2020). "Universal vote-by-mail has no impact on partisan turnout or vote share". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (25): 14052–14056. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11714052T. doi:10.1073/pnas.2007249117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7322007. PMID 32518108.

- ^ a b Young, Ashley (September 23, 2016). "A Complete Guide To Early And Absentee Voting". Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Farley, Robert (April 10, 2020). "Trump's Latest Voter Fraud Misinformation". FactCheck.org. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Taddonio, Patrice (October 20, 2020). "How Associating Mail-in Ballots with Voter Fraud Became a Political Tool". FRONTLINE. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

A more pervasive problem, experts say, is disenfranchisement caused by the proportion of mail-in ballots that are discarded on technicalities

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Signature Verification and Mail Ballots: Guaranteeing Access While Preserving Integrity" (PDF). Stanford University. April 15, 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Daniel (September 18, 2018). "Vote-By-Mail Ballots Cast in Florida" (PDF). ACLU-Florida. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS) 2016 Comprehensive Report" (PDF). Election Assistance Commission. June 28, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Corasaniti, Nick; Saul, Stephanie (April 9, 2020). "Inside Wisconsin's Election Mess: Thousands of Missing or Nullified Ballots". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Wise, Justin (July 30, 2020). "FEC commissioner to Trump: 'No. You don't have the power to move the election'". The Hill.

- ^ "Trump blocks postal funds to stymie mail-in voting". BBC News. August 13, 2020.

- ^ "US Postal Service warns of risks to mail-in votes". BBC News. August 15, 2020.

- ^ Cohen, Zachary (September 3, 2020). "Intelligence bulletin warns Russia amplifying false claims mail-in voting will lead to widespread fraud". CNN.

- ^ Wines, Michael (February 27, 2021). "In Statehouses, Stolen-Election Myth Fuels a G.O.P. Drive to Rewrite Rules". The New York Times.

- ^ Waxman, Olivia (September 28, 2020). "Voting by Mail Dates Back to America's Earliest Years. Here's How It's Changed Over the Years". Time.

- ^ Frank, Megan (May 4, 2021). "Voting By Mail in Pennsylvania Dates Back To Colonial Times". WESA.

- ^ Seitz-Wald, Alex (April 19, 2020). "How do you know voting by mail works? The U.S. military's done it since the Civil War". NBC News. Archived from the original on April 19, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Korb, Lawrence J. (May 18, 2020). "US troops routinely vote by mail. Why can't the rest of America do the same?". Military Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Steinbicker, Paul G. (1938). "Absentee Voting in the United States". American Political Science Review. 32 (5): 898–907. doi:10.2307/1948225. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1948225. S2CID 145709970.

- ^ a b c d e "Voting Outside the Polling Place: Absentee, All-Mail and other Voting at Home Options". www.ncsl.org. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Table 3: States With Permanent Absentee Voting Lists". National Conference of State Legislatures.

- ^ "Lost your ballot? Looking for a dropbox? We've got you covered". The Seattle Times. November 5, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "Absentee Voting and Vote by Mail". U.S. Election Assistance Commission. November 17, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Harwood, Matthew (April 7, 2020). "Why a Vote-by-Mail Option Is Necessary". Brennan Center for Justice. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ Derysh, Igor (June 2, 2020). "'Bill Barr is a liar': Trump AG floats new mail-vote conspiracy experts say 'just couldn't happen'". Salon. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ U.S. Dept. of Commerce. "Discussion of Barcodes/Encoding" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ "Absent Ballot Information". Washoe County, Nev. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions-I lost the envelope for my Vote by Mail ballot, how can I send in my ballot?". Sacramento County, Calif. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ a b Pandey, Maia (October 9, 2024). "Ballot drop boxes will be back for the 2024 election. Here's how to use them". USA Today. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ "VOPP: Table 11: Receipt and Postmark Deadlines for Absentee Ballots". www.ncsl.org. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ "Policies for Election Observers". National Conference of State Legislaturres. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ "Absentee voting myths vs. realities". Federal Voting Assistance Program/U.S. Army. September 25, 2014.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about absentee voting". Federal Voting Assistance Program.

- ^ "THE ELECTION ADMINISTRATION AND VOTING SURVEY: 2016 Comprehensive Report" (PDF). U.S. Election Assistance Commission: 25. June 29, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

- ^ "Two-Thirds of Voters Back Vote-by-Mail in November 2020". NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth. April 21, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ "Two-Thirds of Americans Expect Presidential Election Will Be Disrupted by COVID-19". Pew Research Center – U.S. Politics & Policy. April 28, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Data Dive: Timelines for Pre-Processing Mail Ballots". The Center for Election Innovation & Research. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ Otterbein, Holly (November 3, 2020). "Democrats return nearly three times as many mail-in ballots as Republicans in Pennsylvania". POLITICO. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ Schouten, Fredreka (November 4, 2020). "Why mail-in ballots in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania were counted so late | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved October 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS) 2018 Comprehensive report" (PDF). Election Assistance Commission. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Federal Voting Assistance Program questions and answers". Fvap.gov. Archived from the original on March 22, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "The Uniformed And Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act". U.S. Department of Justice. August 6, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Never Resided in the U.S.?". Federal Voting Assistance Program. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ "Federal Write-in Absentee Ballot" (PDF). FVAP. November 15, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Electronic Transmission of Ballots". www.ncsl.org. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Absentee Voting Information". West Virginia Secretary of State. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ a b Verhovek, Sam Howe (August 26, 1997). "Giant Leap for the Space Crowd: Voting". The New York Times. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- ^ Democracy in Orbit: Chiao to Vote in Space NASA October 21, 2004.

- ^ "Texas Administrative Code". texreg.sos.state.tx.us. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c Koren, Marina (November 8, 2016). "In 1997, He Voted From Space. This Year, He's Happy to Wait in Line on Earth". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ "VOPP: Table 18: States With All-Mail Elections". www.ncsl.org. February 3, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ Ellison, Stephen (May 8, 2020). "All California Voters to Receive Mail-In Ballots for 2020 Election: Newsom". NBC Bay Area. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ Shaw, Adam (May 9, 2020). "Newsom order sending mail-in ballots to all California voters sparks concerns". Fox News. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "California Voter's Choice Act". www.sos.ca.gov. California Secretary of State. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "Historical Vote-By-Mail (Absentee) Ballot Use in California". www.sos.ca.gov. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "California counties slow to sign on to all-mail elections". San Francisco Chronicle. March 18, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ "About California Voter's Choice Act". www.sos.ca.gov. California Secretary of State. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ "Gov. Newsom signs bill making universal vote-by-mail permanent in California". KTLA. September 27, 2021.

- ^ "Mail Voting". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Showalter, Amelia (August 8, 2017). "Colorado 2014: Analysis of Predicted and Actual Turnout" (PDF). Pantheon Analytics. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Lauer, Nancy Cook (June 26, 2019). "Hawaii Opts for Voting by Mail". U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ Hanna, John (May 3, 2020). "Joe Biden Wins Kansas Primary Conducted Exclusively By Mail". HuffPost. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ^ Bowden, John (August 3, 2020). "Nevada governor signs bill to allow mail-in voting after Trump promises legal challenge". The Hill. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Swanson, Ian (August 3, 2020). "Trump vows challenge to Nevada bill expanding mail-in voting". The Hill. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Balluck, Kyle (August 4, 2020). "Trump shifts, encourages vote by mail – in Florida". The Hill. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Swanson, Ian (August 4, 2020). "Trump notes GOP governor when asked why he backs mail-in voting in Florida". The Hill. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Durkee, Alison. "Nevada Expands Mail-In Voting As Other Battleground States Pass Restrictions". Forbes. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Brent Johnson (May 15, 2020). "N.J.'s July 7 primary election will be mostly vote-by-mail during coronavirus pandemic, Murphy says". NJ.com. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ "Why Voter Turnout In Oregon Is Incredibly High". Talking Points Memo. November 23, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ "Voting Rights Roundup: Virginia Democrats advance redistricting reform measures". Daily Kos. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "Vermont Legislature sends mail-in voting bill to governor". AP News. May 18, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Reid (June 8, 2021). "Vermont governor signs mail-in voting bill". The Hill. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Grygiel, Chris (April 5, 2011). "Vote-by-mail is now the law in Washington". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on April 8, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ Keith Ervin (May 25, 1990). "Vote-by-mail gets new look in wake of low-voter turnout". The Seattle Times.

- ^ a b Tsong, Nicole (August 19, 2009). "First big all-mail election results posted smoothly – Vote by Mail". The Seattle Times.

- ^ Pierce County Auditor. "Elections". Pierce County, Washington. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "Pre-paid ballot postage is coming for all of Washington State". Curbed Seattle. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- ^ "National Vote at Home Coalition (NVAHC) press release" (PDF). National Vote at Home Coalition. April 10, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Kelly, Devin (April 5, 2018). "Anchorage's vote-by-mail election was supposed to boost turnout. It shattered a record". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "National Vote at Home Coalition press release" (PDF). National Vote at Home Coalition. May 17, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "Maryland city is 1st in state to adopt mail-in voting format". WTOP. Associated Press. April 11, 2018. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 64" (PDF). State of Connecticut. February 7, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Expansion of Voting Before Election Day, 2000–2024". The Center for Election Innovation & Research. Retrieved September 8, 2024.

- ^ Jordan Williams (June 18, 2021). "Illinois governor signs law expanding curbside voting, permanent vote by mail". The Hill.

- ^ "Gov. Newsom signs bill making universal vote-by-mail permanent in California". September 27, 2021.

- ^ B24-0507 - Elections Modernization Amendment Act of 2021. Council of the District of Columbia.

- ^ Mullin, Megan; Kousser, Thad; Arceneaux, Kevin (2009). Get Out the Vote-by-Mail? A Randomized Field Experiment Testing the Effect of Mobilization in Traditional and Vote-by-Mail Precincts. APSA 2009 Toronto Meeting Paper. Social Science Research Network.

- ^ "Elections: Issues Related to Registering Voters and Administering Elections" (PDF). U.S. Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO). June 2016.

- ^ Fessler, Pam; Moore, Elena (August 22, 2020). "More Than 550,000 Primary Absentee Ballots Rejected In 2020, Far Outpacing 2016". NPR.

- ^ a b c d Farley, Robert (April 10, 2020). "Trump's Latest Voter Fraud Misinformation". FactCheck.org. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Foley, Edward B. "Why Vote-by-Mail Could be a Legal Nightmare in November". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Similar summary by Mark Braden, former chief counsel for the Republican National Committee, "The shortcomings of various systems across the country in recount situations, the vast majority of the time, involve mail voting." at 22 minutes in webinar at the National Conference of State Legislatures

- ^ "Who Can Vote? – A News21 2012 National Project". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Kahn, Natasha and Corbin Carson. "Investigation: election day fraud "virtually nonexistent"". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ "Russian Targeting of Election Infrastructure During The 2016 Election: Summary of Draft SSCI Recommendations" (PDF). US Senate Intelligence Committee.

- ^ a b "28 Million Mail-In Ballots Went Missing in Last Four Elections". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Kenney, Andrew (July 17, 2024). "Hundreds of ballots never reached voters in Dolores County; race may be decided by three votes". Durango Herald. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ Service, The New York Times. "'Tainted' Pa. Senate election is voided". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "West Virginia mail carrier charged with attempted absentee ballot application fraud". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Harvey, Matt (December 4, 2020). "Pendleton County West Virginia mail carrier's sentence for attempted election fraud put on hold". WV News. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

Elkins, W.Va. (WV News) Sentencing for a Pendleton County mail carrier who changed five mail-in voting requests for Democrat ballots to requests for Republican ballots has been put on hold. Thomas Cooper, 47, of Dry Fork, had been scheduled to be sentenced Friday for attempt to defraud the residents of West Virginia of a fair election, and injury to the mail. He could face up to 5 years in prison on the first count and up to 3 years on the second.

- ^ "Heavily Republican Utah likes voting by mail, but national GOP declares war on it". Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Lai, Jonathan (May 18, 2020). "Montgomery County sent out thousands of Pa. absentee ballots with flawed instructions". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Stein, Linda (October 29, 2021). "Delco Officials Admit Sending Hundreds Of Ballots To Wrong Voters". Delaware Valley Journal. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Lai, Jonathan (May 26, 2020). "Montco sent 2,000 Pa. voters the wrong ballots for next week's primary". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ "Provisional Ballots". www.ncsl.org. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Glenn R. Simpson; Evan Perez (December 19, 2000). "'Brokers' Exploit Absentee Voters; Elderly Are Top Targets for Fraud". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Bender, William. "Nursing home resident's son: 'That's voter fraud'". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "The real vote-fraud opportunity has arrived: casting your ballot by mail". NBC News. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

Curtis Gans, director of the Center for the Study of the American Electorate, said vote-buying and bribery could occur more easily with mail voting and absentee voting. At a polling place, someone who bribed voters would have no way to verify that the bribe worked. A person who bribes mail voters could watch as they mark ballots or even mark ballots for them.

- ^ Rahman, Jayed (May 12, 2020). "Election board decides not to count more than 800 Paterson ballots amid voter fraud allegations". Paterson Times. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "What is ballot harvesting and how is it affecting Southern California elections?". Orange County Register. May 17, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Central figure in North Carolina absentee ballot fraud indicted on multiple counts". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Rushing, Ellie (December 17, 2021). "Thieves are stealing checks from USPS collection boxes across Philly — and trying to get mail carriers' keys". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ McDade, Mary Beth (August 23, 2021). "300 recall ballots, drugs, multiple driver's licenses found in vehicle of passed out felon: Torrance police". KTLA 5. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "Voter finds keys left inside lock of LA County ballot drop-off box". CBS Los Angeles. November 2, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ "Public Safety Briefs". Ventura County Star. September 5, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2021. "envelope bar codes that were duplicated by the manufacturer... K&H Election Services"

- ^ "Notice of Print Vendor Error" (PDF). Ventura County Clerk-Recorder. September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2021.

- ^ Service, Capital News. "In 2018, nearly 7,000 absentee ballots arrived too late to be counted". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "If you vote by mail in Florida, it's 10 times more likely that ballot won't count". Miami Herald. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- ^ "Vote-by-mail experiment reveals potential problems within postal voting system ahead of November election". CBS News. July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Mazzei, Patricia (October 28, 2016). "Two women busted for election fraud in Miami-Dade in 2016". Miami Herald. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Judge hears testimony in Hawkins case". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Beilman, Elizabeth. "Jeffersonville City Council At-large recount tally sheets show vote differences". Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Buchanan, Larry; Parlapiano, Alicia (October 7, 2020). "Two of These Mail Ballot Signatures Are by the Same Person. Which Ones?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Table 14: How States Verify Voted Absentee/Mail Ballots". National Conference of State Legislatures. January 22, 2024. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ a b These systems handle scanned ("offline") signatures from multiple people ("WI, writer-independent"). Hafemann, Luiz G.; Sabourin, Robert; Oliveira, Luiz S. (2017). "Offline handwritten signature verification — Literature review". 2017 Seventh International Conference on Image Processing Theory, Tools and Applications (IPTA). IEEE. pp. 1–8. arXiv:1507.07909. doi:10.1109/IPTA.2017.8310112. ISBN 978-1-5386-1842-4. S2CID 206932295.

- ^ a b Armitage, Susie (November 5, 2018). "Handwriting Disputes Cause Headaches for Some Absentee Voters". ProPublica. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Signature Verification and Cure Process" (PDF). US Election Assistance Commission. May 20, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ "Colorado Secretary of State Signature Verification Guide" (PDF). Colorado Secretary of State. September 13, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "2 CCR 20960(b) and (j)" (PDF). California Sec. of State. October 1, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Levine, Sam (July 8, 2020). "'Unbelievably unfair': thousands of Americans face having votes rejected in election". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Verification of Absentee Ballots". National Council of State Legislators. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Daniel (February 16, 2021). "Casting, Rejecting, and Curing Vote-by-Mail Ballots in Florida's 2020 General Election" (PDF). All Voting Is Local. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Mearhoff, Sarah (August 19, 2022). "Vermonters 'cured' majority of defective ballots in primary voting, resulting in low rejection rate". VTDigger. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Inbound Ballot Process" (PDF). US Election Assistance Commission. May 20, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Srihari, Sargur N. (August 12, 2010). "Computational Methods for Handwritten Questioned Document Examination 1 FINAL REPORT to Dept. of justice Award Number: 2004-IJ-CX-K050". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.186.175.

- ^ Bibi, Kiran; Naz, Saeeda; Rehman, Arshia (January 1, 2020). "Biometric signature authentication using machine learning techniques: Current trends, challenges and opportunities". Multimedia Tools and Applications. 79 (1): 289–340. doi:10.1007/s11042-019-08022-0. ISSN 1573-7721. S2CID 199576552.

- ^ Igarza, Juan; Goirizelaia, Iñaki; Espinosa, Koldo; Hernáez, Inmaculada; Méndez, Raúl; Sanchez, Jon (November 26, 2003). Online Handwritten Signature Verification Using Hidden Markov Models. CIARP 2003. Vol. 2905. pp. 391–399. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-24586-5_48.

- ^ "SignatureXpert for Vote by Mail" (PDF). Parascript. May 5, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Agilis Ballot Packet Sorting System" (PDF). Runbeck. November 7, 2019.

- ^ "Criterion Elevate". www.fluenceautomation.com. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Vote-By-Mail Best Practices Webinar Series". www2.bluecrestinc.com. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Sita, Jodi; Found, Bryan; Rogers, Douglas K. (September 2002). "Forensic Handwriting Examiners' Expertise for Signature Comparison". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 47 (5): 1117–24. doi:10.1520/JFS15521J. ISSN 0022-1198. PMID 12353558.

- ^ a b c "Vote at Home Policy Actions: 1 and 2 Stars" (PDF). National Vote at Home Institute. May 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Salame, Richard (June 18, 2020). "As States Struggle With Vote-by-Mail, "Many Thousands, If Not Millions" of Ballots Could Go Uncounted in November". Type Investigations. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ O'Dea, Colleen (June 10, 2020). "One in 10 Ballots Rejected in Last Month's Vote-by-Mail Elections". NJ Spotlight. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "1 in 5 Ballots Rejected as Fraud Is Charged in N.J. Mail-In Election". RealClearPolitics. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ NJ.com, Rodrigo Torrejon | NJ Advance Media for (June 25, 2020). "Voting fraud charges filed against Paterson councilman and councilman-elect". nj. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Cao, Diana (June 24, 2020). "Florida Election Analysis" (PDF). Stanford-MIT Healthy Elections Project. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Baringer, Anna; Herron, Michael C.; Smith, Daniel A. (April 25, 2020). "Voting by Mail and Ballot Rejection: Lessons from Florida for Elections in the Age of the Coronavirus" (PDF). University of Florida. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ Shino, Enrijeta; Mara Suttmann-Lea; Daniel A. Smith (May 19, 2020). "Voting by Mail in a VENMO World: Assessing Rejected Absentee Ballots in Georgia" (PDF). University of Florida. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Wilkie, Jordan (October 12, 2018). "Exclusive: High Rate of Absentee Ballot Rejection Reeks of Voter Suppression". Who What Why. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Viebeck, Elise (July 16, 2020). "Tens of thousands of mail ballots have been tossed out in this year's primaries. What will happen in November?". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "Signature verification could complicate massive mail ballot count, experts say". ABC News.

- ^ "What to Consider When You're Expecting More Absentee Voting" (PDF). National Conference of State Legislatures. May 13, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ "'We've got to get going.' States under pressure to plan for the general election amid a pandemic". PBS NewsHour. May 4, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Farley, Robert (June 25, 2020). "Trump's Shaky Warning About Counterfeit Mail-In Ballots". Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Ballot Printing :: California Secretary of State". www.sos.ca.gov. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Padilla, Alex (August 5, 2020). "General Election: Ballot Tint and Watermark Assignment" (PDF). California Secretary of State.

- ^ Fox, Patricia (June 19, 2012). "Statement of Reasons". U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ ES&S (April 30, 2015). "Ballot Production Guide" (PDF). Citizens Oversight Projects. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ a b ES&S (July 22, 2019). "EVS 6042 CA Election Management System" (PDF). California Sec of State. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ Alfred Ng (August 28, 2020). "How to commit mail-in voting fraud (It's nearly impossible)". CNET. Wikidata Q99676175.

- ^ "2 CCR 20991(b)(9) and (11)" (PDF). California Sec. of State. October 1, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ "Ballot Printer/Ballot on Demand (BOD) Certification :: California Secretary of State". www.sos.ca.gov. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Opilo, Emily (July 15, 2020). "Maryland searching for new ballot printing vendor for November elections after problems in primary". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Wollan, Malia (October 26, 2020). "20,000 Ballots an Hour, With Paper and Ink by the Ton". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Fifield, Jen (April 28, 2021). "Arizona election auditors are running ballots under UV light. What could they be looking for?". Arizona Republic. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ Hofmann, Sarah (February 10, 2024). "Why mail-in ballots are confusing some Riverside County voters". Press Enterprise. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Epstein, Reid J. (October 16, 2020). "In Ohio, a Printing Company Is Overwhelmed and Mail Ballots Are Delayed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Goodkind, Nicole (March 30, 2020). "USPS warns it might have to shutter by June as $2 trillion coronavirus stimulus package provides no funding". Fortune. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Blumenthal, Paul (May 6, 2020). "It's Time To End Election Night In America". HuffPost. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Li, Yimeng; Hyun, Michelle; Alvarez, R. Michael (March 27, 2020). "Why Do Election Results Change After Election Day? The "Blue Shift" in California Elections". American Government and Politics. doi:10.33774/apsa-2020-s43xx. S2CID 242728072.

- ^ "Beware the 'blue mirage' and the 'red mirage' on election night". NBC News. November 3, 2020.

- ^ Hyun, Michelle (March 30, 2020). "The Blue Shift in California Elections | Election Updates". electionupdates.caltech.edu. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Lai, Jonathan (January 27, 2020). "How does a Republican lead on election night and still lose Pennsylvania? It's called the 'blue shift.'". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ a b Foley, Edward B. (November 12, 2013). "A Big Blue Shift: Measuring an Asymmetrically Increasing Margin of Litigation". Journal of Law and Politics. 27. SSRN 2353352.

- ^ a b Foley, Edward B.; Stewart III, Charles (August 28, 2015). "Explaining the Blue Shift in Election Canvassing". SSRN 2653456.

- ^ Chuck Squatrigli (November 4, 2008). "It's Time for Drive-Thru Voting". Wired. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- ^ "Voting at Home Across the States" (PDF). National Vote at Home Institute. November 12, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Mailed-out Ballot Return Choices" (PDF). National Vote at Home Institute. July 20, 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Calicchio, Dom (May 21, 2020). "Pelosi touts $3.6B vote-by-mail bill, now called 'Voting at Home,' after Trump warnings to Michigan, Nevada". Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Hindi, Saja (May 24, 2020). "The president says all-mail ballots benefit Democrats and lead to rampant voter fraud. Colorado says no". Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Bump, Philip. "Analysis | Trump just said what Republicans have been trying not to say for years" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Steinhauser, Paul (May 26, 2020). "Trump charges voting by mail will result in 'rigged election'". Fox News. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Yen, Hope (August 8, 2020). "AP FACT CHECK: Trump misleads on mail ballots, virus vaccine". AP News. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Trump floats delaying election despite lack of authority to do so". CNN. July 30, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ "Trump Suggests Unprecedented Delay to November Election – But Congress Sets the Date". www.nbcnewyork.com. July 30, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ "Trump floats idea of delaying election, congressional Republicans reject idea". Reuters. July 30, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ "Trump floats delaying 2020 election". Politico. July 30, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Ellie Kaufman; Marshall Cohen; Jason Hoffman; Nicky Robertson (August 13, 2020). "Trump says he opposes funding USPS because of mail-in voting". CNN. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "Federal Judge Rules Trump and Louis DeJoy Waged 'Politically Motivated Attack' Against USPS, Will Rescind Recent Changes". September 17, 2020.

- ^ Cox, Erin; Viebeck, Elise; Bogage, Jacob; Ingraham, Christopher (August 14, 2020). "Postal Service warns 46 states their voters could be disenfranchised by delayed mail-in ballots". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via Boston Globe.

- ^ Berman, Russell (August 14, 2020). "What Really Scares Voting Experts About the Postal Service". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Naylor, Brian (March 9, 2021). "Postal Service Delivered Vast Majority Of Mail Ballots On Time, Report Finds". National Public Radio. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "Service Performance of Election and Political Mail During the November 2020 General Election" (PDF). USPS Office of Inspector General. March 5, 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "New USPS election division will oversee mail-in ballots". Associated Press. July 28, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Rutenberg, Jim; Haberman, Maggie; Corasaniti, Nick (April 10, 2020). "Why Republicans Are So Afraid of Vote-by-Mail". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Broadwater, Luke (October 12, 2020). "Both Parties Fret as More Democrats Request Mail Ballots in Key States". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ Viebeck, Elise. "Courts view GOP fraud claims skeptically as Democrats score key legal victories over mail voting". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

Further reading