Portal:Middle Ages/Selected article/16

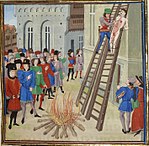

To be hanged, drawn and quartered (less commonly "hung, drawn and quartered") was from 1351 a penalty in England for men convicted of high treason, although the ritual was first recorded during the reigns of King Henry III (1216–1272) and his successor, Edward I (1272–1307). Convicts were fastened to a hurdle, or wooden panel, and drawn by horse to the place of execution, where they were hanged (almost to the point of death), emasculated, disembowelled, beheaded and quartered (chopped into four pieces). Their remains were often displayed in prominent places across the country, such as London Bridge. For reasons of public decency, women convicted of high treason were instead burnt at the stake.

The severity of the sentence was measured against the seriousness of the crime. As an attack on the monarch's authority, high treason was considered an act deplorable enough to demand the most extreme form of punishment, and although some convicts had their sentences modified and suffered a less ignominious end, over a period of several hundred years many men found guilty of high treason were subjected to the law's ultimate sanction. This included many English Catholic priests executed during the Elizabethan era, and several of the regicides involved in the 1649 execution of King Charles I.

Although the Act of Parliament that defines high treason remains on the United Kingdom's statute books, during a long period of 19th-century legal reform the sentence of hanging, drawing and quartering was changed to drawing, hanging until dead, and posthumous beheading and quartering, before being rendered obsolete in England in 1870. The death penalty for treason was abolished in 1998.