Portal:Linguistics/Featured article

Instructions

[edit]- Add a new article to the next available subpage.

- The "blurb" for all Featured articles should be approximately 10 lines, for appropriate formatting in the portal main page.

- Update "max=" to new total for its {{Random portal component}} on the main page.

Articles

[edit]Featured article 1

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/1

Swedish is a North Germanic language spoken predominantly in Sweden, part of Finland, and on the autonomous Åland islands, by a total of over 9 million speakers. Standard Swedish is the national language that evolved from the Central Swedish dialects in the 19th century and was well-established by the first decades of the 20th century. While distinct regional varieties still exist, influenced by the older rural dialects, the spoken and written language is uniform and standardized, with a 99% literacy rate among adults. Some of the genuine dialects differ considerably from the standard language in grammar and vocabulary and are not always mutually intelligible with Standard Swedish. These dialects are confined to rural areas and spoken by a rather limited group of people of low education and social mobility. Swedish is distinguished by its prosody, which differs considerably between varieties. It includes both lexical stress and some tonal qualities. Swedish is also notable for the voiceless dorso-palatal velar fricative, a sound found in many dialects, including the more prestigious forms of the standard language.

Featured article 2

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/2 Truthiness is a quality characterizing a "truth" that a person making an argument or assertion claims to know intuitively "from the gut" or because it "feels right" without regard to evidence, logic, intellectual examination, or facts.

American television comedian Stephen Colbert coined the word in this meaning as the subject of a segment called "The Wørd" during the pilot episode of his political satire program The Colbert Report on October 17, 2005. By using this as part of his routine, Colbert satirized the misuse of appeal to emotion and "gut feeling" as a rhetorical device in contemporaneous socio-political discourse. He particularly applied it to U.S. President George W. Bush's nomination of Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court and the decision to invade Iraq in 2003. Colbert later ascribed truthiness to other institutions and organizations, including Wikipedia. Colbert has sometimes used a Dog Latin version of the term, "Veritasiness".

Truthiness, although a "stunt word", was named Word of the Year for 2005 by the American Dialect Society and for 2006 by Merriam-Webster. Linguist and OED consultant Benjamin Zimmer pointed out that the word truthiness already had a history in literature and appears in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), as a derivation of truthy, and The Century Dictionary, both of which indicate it as rare or dialectal, and to be defined more straightforwardly as "truthfulness, faithfulness". Responding to claims, Colbert explained the origin of his word as: "Truthiness is a word I pulled right out of my keister".

Featured article 3

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/3

The IPA is designed to represent only those qualities of speech that are part of oral language: phones, phonemes, intonation, and the separation of words and syllables. To represent additional qualities of speech, such as tooth gnashing, lisping, and sounds made with a cleft palate, an extended set of symbols called the Extensions to the IPA may be used.

Featured article 4

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/4

Latin pronunciation continually evolved over the centuries, making it difficult for speakers in one era to know how Latin was spoken in prior eras. A given phoneme may be represented by different letters in different periods. This article deals primarily with modern scholarship's best reconstruction of Classical Latin's phonemes (phonology) and the pronunciation and spelling used by educated people in the late Republic and then touches upon later changes and other variants.

Featured article 5

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/5

One of the most important aspects of Irish phonology is that almost all consonants come in pairs, with one having a "broad" pronunciation and the other a "slender" one. Broad consonants are velarized, that is, the back of the tongue is pulled back and slightly up in the direction of the soft palate while the consonant is being articulated. Slender consonants are palatalized, which means the tongue is pushed up toward the hard palate during the articulation. The contrast between broad and slender consonants is crucial in Irish, because the meaning of a word can change if a broad consonant is substituted for a slender consonant or vice versa. For example, the only difference in pronunciation between the words bó ('cow') and beo ('alive') is that bó is pronounced with a broad b sound, while beo is pronounced with a slender b sound. The contrast between broad and slender consonants plays a critical role not only in distinguishing the individual consonants themselves, but also in the pronunciation of the surrounding vowels, in the determination of which consonants can stand next to which other consonants, and in the behavior of words that begin with a vowel. This broad/slender distinction is similar to the hard/soft one of several Slavic languages, like Russian.

The Irish language shares a number of phonological characteristics with its nearest linguistic relatives, Scottish Gaelic and Manx, as well as with Hiberno-English, the language with which it is most closely in contact.

Featured article 6

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/6

Gwoyeu Romatzyh (GR) is a system for writing Chinese in the Latin alphabet. It was developed in the 1920s by a group of linguists led by Y.R. Chao, and is unique in its use of "tonal spelling" to indicate the four tones of Mandarin. Tones are a fundamental part of the Chinese language: using the wrong tone sounds as puzzling as if one said bud in English when one means bed or bad. Unlike other systems, which indicate tones with accents or numbers, GR modifies the spelling of the syllable: the four tones of guo, for example, are illustrated (the second tone gwo, meaning "nation", occurs in Gwoyeu). Some teachers believe that these distinctive spellings may help foreign students remember the tones. In 1928 China adopted GR as the nation's official romanization system. Although GR was mainly used in dictionaries, its proponents hoped one day to establish it as a writing system for a reformed Chinese script. But despite support from trained linguists in China and overseas, GR met with public indifference and even hostility due to its complexity. Eventually GR lost ground to Pinyin and other later romanization systems. However, its influence is still evident, as several of the principles introduced by its creators have been used in romanization systems that followed it. (more...)

Featured article 7

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/7

Rongorongo is a system of glyphs discovered in the 19th century on Easter Island that appears to be writing or proto-writing. It has not been deciphered despite numerous attempts. Although some calendrical and what might prove to be genealogical information has been identified, not even these glyphs can be read. If rongorongo does prove to be writing, it would be one of only three or four known independent inventions of writing in human history. Two dozen wooden objects bearing rongorongo inscriptions, some heavily weathered, burned, or otherwise damaged, were collected in the late 19th century and are now scattered in museums and private collections. The objects are mostly tablets made from irregular pieces of wood, sometimes driftwood, but include a chieftain's staff, a bird-man statuette, and two reimiro ornaments. Oral history suggests that only a small elite was ever literate and that the tablets were sacred. Authentic rongorongo texts are written in alternating directions, a system called reverse boustrophedon. In the case of the tablets these lines are often inscribed in shallow fluting carved into the wood. The glyphs have a characteristic outline appearance and include human, animal, plant, artifact and geometric forms. (more...)

Featured article 8

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/8

The Gbe languages form a cluster of about 20 related languages stretching across the area between eastern Ghana and western Nigeria. The total number of speakers of Gbe languages is between four and eight million. The most widely spoken Gbe language is Ewe, followed by Fon. The Gbe languages belong to the Kwa branch of the Niger–Congo languages, and break up into five major dialect clusters: Ewe, Fon, Aja, Gen, and Phla–Pherá. In the late 18th century, many speakers of Gbe were enslaved and transported to the New World, causing Gbe languages to play a role in the genesis of several Caribbean creole languages. In the first half of the twentieth century, the Africanist Diedrich Hermann Westermann was one of the most prolific contributors to the study of Gbe. The first internal classification of the Gbe languages was published in 1988 by H.B. Capo, followed by a comparative phonology in 1991. The Gbe languages are tonal, isolating languages and the basic word order is subject–verb–object.

Featured article 9

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/9 In phonology, minimal pairs are pairs of words or phrases in a particular language, which differ in only one phonological element, such as a phone, phoneme, toneme or chroneme and have a distinct meaning. They are used to demonstrate that two phones constitute two separate phonemes in the language.

As an example for English vowels, the pair "let" + "lit" proves that the phones [ɛ] (in let) and [ɪ] (in lit) do in fact represent distinct phonemes /ɛ/ and /ɪ/. An example for English consonants is the minimal pair of "pat" + "bat". In phonetics, this pair, like any other, differs in number of ways. In this case, the contrast appears largely to be conveyed with a difference in the voice onset time of the initial consonant as the configuration of the mouth is same for [p] and [b]; however, there is also a possible difference in duration, which visual analysis using high quality video supports.

Featured article 10

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/10

Nahuatl is a group of related languages and dialects of the Aztecan, or Nahuan, branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family, all of which are indigenous to Mesoamerica and are spoken by an estimated 1.5 million Nahua people, mostly in Central Mexico. Nahuatl has been spoken in Central Mexico since at least the 7th century AD. At the time of the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the early 16th century it was the language of the Aztecs, who dominated central Mexico during the Late Postclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology. The expansion and influence of the Aztec Empire led to the dialect spoken by the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan becoming a prestige language in Mesoamerica in this period. With the introduction of the Latin alphabet, Nahuatl also became a literary language and many chronicles, grammars, works of poetry, administrative documents and codices were written in the 16th and 17th centuries. This early literary language based on the Tenochtitlan dialect has been labeled Classical Nahuatl and is among the most-studied and best-documented languages of the Americas. Today, Nahuan dialects are spoken in scattered communities mostly in rural areas. There are considerable differences between dialects and some are mutually unintelligible. No modern dialects are identical to Classical Nahuatl, but those spoken in and around the Valley of Mexico are generally more closely related to it than those on the periphery. (more...)

Featured article 11

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/11 Philosophy of language is the reasoned inquiry into the nature, origins, and usage of language. As a topic, the philosophy of language for Analytic Philosophers is concerned with four central problems: the nature of meaning, language use, language cognition, and the relationship between language and reality. For Continental philosophers, however, the philosophy of language tends to be dealt with, not as a separate topic, but as a part of Logic, History or Politics. (See the section "Language and Continental Philosophy" below.)

First, philosophers of language inquire into the nature of meaning, and seek to explain what it means to "mean" something. Topics in that vein include the nature of synonymy, the origins of meaning itself, and how any meaning can ever really be known. Another project under this heading of special interest to analytic philosophers of language is the investigation into the manner in which sentences are composed into a meaningful whole out of the meaning of its parts.

Featured article 12

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/12

The decipherment of rongorongo began with the discovery of the rongorongo tablets on Easter Island in the late nineteenth century. As with most undeciphered scripts, many of the proposals have been fanciful. Apart from a portion of one tablet which has been shown to deal with a lunar calendar, none of the texts are understood, and even the calendar cannot actually be read. There are three serious obstacles to decipherment: the small number of remaining texts, comprising only 15,000 legible glyphs; the lack of context in which to interpret the texts, such as illustrations or parallels to texts that can be read; and the fact that the modern Rapanui language is heavily mixed with Tahitian and is unlikely to closely reflect the language of the tablets—especially if they record a specialized register such as incantations—while the few remaining examples of the old language are heavily restricted in genre and may not correspond well to the tablets either. Since a proposal by Butinov and Knorozov in the 1950s, the majority of philologists, linguists, and cultural historians have taken the line that rongorongo was not true writing but proto-writing, that is, an ideographic- and rebus-based mnemonic device. If it is the case that rongorongo is proto-writing, then it is unlikely to ever be deciphered. Oral history suggests that only a small elite were ever literate, and that the tablets were considered sacred. (more...)

Featured article 13

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/13

The word thou was a second person singular pronoun in English. It is now largely archaic, having been replaced in almost all contexts by "you". Thou is the nominative form; the oblique/objective form is thee (functioning as both accusative and dative), and the possessive is thy or thine. Originally, thou was simply the singular counterpart to the plural pronoun ye, derived from an ancient Indo-European root. In imitation of continental practice, thou was later used to express intimacy, familiarity, or even disrespect while another pronoun, you, the oblique/objective form of ye, was used for formal circumstances (see T–V distinction). After thou fell out of fashion, it was primarily retained in fixed ritual settings, so that for some speakers, it came to connote solemnity or even formality. Thou persists, sometimes in altered form, in regional dialects of England and Scotland. The disappearance of the singular-plural distinction has been compensated for through the use of neologisms in various dialects. Colloquial American English, for example, contains plural constructions that vary regionally, including y'all, youse, and you guys. (more...)

Featured article 14

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/14

In Chinese, classifiers are words that must be used whenever a noun is modified by a number or a demonstrative such as "this" and "that". There are as many as 150 different classifiers, and many nouns are associated with certain ones—for example, flat objects such as tables use the classifier zhāng, whereas long objects such as lines use tiáo. How exactly these classifier–noun associations are formed has been a subject of debate, with some linguists proposing that they are based on innate semantic features (e.g., all nouns with "long" features use a certain classifier), and others suggesting that they are motivated by analogy to prototypical pairings (e.g., dictionaries and textbooks use whatever the more general noun "book" uses). There is also, however, a "general classifier", gè, which can be used in place of the specific classifiers; in informal speech, this one is used far more than any other. Furthermore, speakers often choose to use only a bare noun, dropping both the classifier and the number or demonstrative preceding it; therefore, some linguists believe that classifiers are used more for pragmatic reasons, such as foregrounding new information, rather than for strict grammatical reasons. (more...)

Featured article 15

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/15

Nafaanra is a Senufo language spoken in northwest Ghana, along the border with Côte d'Ivoire, east of Bondouko. It is spoken by approximately 61,000 people. Its speakers call themselves Nafana; others call them Banda or Mfantera. Like other Senufo languages, Nafaanra is a tonal language. It is somewhat of an outlier in the Senufo language group, with the geographically closest relatives, the Southern Senufo Tagwana–Djimini languages, approximately 200 kilometres to the west, on the other side of Comoé National Park. The uses subject–object–verb word order, similar to Latin and Japanese. Like other Niger–Congo languages it has a noun class system where nouns are classified according to five different genders, which also affects pronouns, adjectives and copulas. The phonology features a distinction between the length of vowels and whether they are oral or nasal (as in French or Portuguese). There are also three distinct tones, a feature shared with the other Senufo languages. Nafaanra grammar features both tense and aspect which are marked with particles. Numbers are mainly formed by adding cardinal numbers to the number 5 and by multiplying the numbers 10, 20 and 100. (more...)

Featured article 16

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/16

Mayan languages are a language family spoken in Mesoamerica and northern Central America. Mayan languages are spoken by at least 6 million indigenous Maya, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, and Belize. The Mayan language family is one of the best documented and most studied in the Americas. Modern Mayan languages descend from Proto-Mayan, a language thought to have been spoken at least 5000 years ago; it has been partially reconstructed using the comparative method. Mayan languages form part of the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area, an area of linguistic convergence developed throughout millennia of interaction between the peoples of Mesoamerica. All Mayan languages display the basic diagnostic traits of this linguistic area. During the pre-Columbian era of Mesoamerican history, some Mayan languages were written in the Maya hieroglyphic script. Its use was particularly widespread during the Classic period of Maya civilization. The surviving corpus of over 10,000 known individual Maya inscriptions on buildings, monuments, pottery and bark-paper codices, combined with the rich postcolonial literature in Mayan languages written in the Latin alphabet, provides a basis for the modern understanding of pre-Columbian history unparalleled in the Americas. (more...)

Featured article 17

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/17

Black American Sign Language is a dialect of American Sign Language (ASL) spoken most commonly by deaf African Americans in the United States. The divergence from ASL was influenced largely by the segregation of schools in the American South. Like other schools at the time, schools for the deaf were segregated based upon race, creating two language communities among deaf signers: White deaf signers at White schools and Black deaf signers at Black schools. Today, BASL is still used by signers in the South despite schools having been legally desegregated since 1954.

Linguistically, BASL differs from other varieties of ASL in its phonology, syntax, and lexicon. BASL tends to have a larger signing space meaning that some signs are produced further away from the body than in other dialects. Signers of BASL also tend to prefer two-handed variants of signs while signers of ASL tend to prefer one-handed variants. Some signs are different in BASL as well, with some borrowings from African American English. (more...)

Featured article 18

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/18

Tamil is a Dravidian language related to Kannada, Telugu and Malayalam, among others. As one of the few living classical languages, it has an unbroken literary tradition of over two millennia, with the earliest writings having been dated to circa 500 B.C. Tamil, like other Dravidian languages, is agglutinative and the writing is largely phonetic. It is spoken by a majority of people in Tamil Nadu and northern and north-eastern Sri Lanka, while a significant emigrant population lives in Singapore, Malaysia and other parts of the world. It is officially recognised in India, Sri Lanka, Singapore, and South Africa. (more...)

Featured article 19

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/19

The Bengali Language Movement was a political movement in former East Bengal (today Bangladesh) advocating the recognition of the Bengali language as an official language of the then-Dominion of Pakistan in order to allow its use in government affairs, the continuation of its use as a medium of education, its use in media, currency and stamps, and to maintain its writing in the Bengali script.

In 1948, the Government of the Dominion of Pakistan ordained Urdu as the sole national language, sparking extensive protests among the Bengali-speaking majority of East Bengal. Facing rising sectarian tensions and mass discontent with the new law, the government outlawed public meetings and rallies. The students of the University of Dhaka and other political activists defied the law and organised a protest on 21 February 1952. The movement reached its climax when police killed student demonstrators on that day. The deaths provoked widespread civil unrest. After years of conflict, the central government relented and granted official status to the Bengali language in 1956. In 1999, UNESCO declared 21 February as International Mother Language Day, in tribute to the Language Movement and the ethno-linguistic rights of people around the world.

The Language Movement catalysed the assertion of Bengali national identity in East Bengal and later East Pakistan, and became a forerunner to Bengali nationalist movements, including the 6-Point Movement and subsequently the Bangladesh Liberation War and Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. In Bangladesh, 21 February is observed as Language Movement Day, a national holiday. The Shaheed Minar monument was constructed near Dhaka Medical College in memory of the movement and its victims.

Featured article 20

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/20

The Linguistic Society of America (LSA) is a learned society for the field of linguistics. Founded at the end of 1924 in New York City, the LSA works to promote the scientific study of language. The Society publishes two scholarly journals, Language and the open access journal Semantics and Pragmatics. Its annual meetings, held every winter, foster discussion amongst its members through the presentation of peer-reviewed research, as well as conducting official business of the Society. Since 1928, the LSA has offered training to linguists through courses held at its biennial Linguistic Institutes held in the summer. The LSA and its 3,500 members work to raise awareness of linguistic issues with the public and contributes to policy debates on issues including bilingual education and the preservation of endangered languages.

Featured article 21

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/21 Ain't is a contraction for am not, is not, are not, has not, and have not in the common English language vernacular. In some dialects ain't is also used as a contraction of do not, does not, and did not. The development of ain't for the various forms of to be not, to have not, and to do not occurred independently, at different times. The usage of ain't for the forms of to be not was established by the mid-18th century, and for the forms of to have not by the early 19th century.

The usage of ain't is a perennial subject of controversy in English. Ain't is commonly used by many speakers in oral or informal settings, especially in certain regions and dialects. Its usage is often highly stigmatized, and it may be used as a marker of socio-economic or regional status or education level. Its use is generally considered non-standard by dictionaries and style guides except when used for rhetorical effect, and it is rarely found in formal written works.

Featured article 22

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/22

Avram Noam Chomsky (/noʊm ˈtʃɒmski/ nohm CHOM-skee; born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a major figure in analytic philosophy and one of the founders of the field of cognitive science. He is a laureate professor of linguistics at the University of Arizona and an institute professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Among the most cited living authors, Chomsky has written more than 150 books on topics such as linguistics, war, and politics. In addition to his work in linguistics, since the 1960s Chomsky has been an influential voice on the American left as a consistent critic of U.S. foreign policy, contemporary capitalism, and corporate influence on political institutions and the media. (Full article...)

Featured article 23

Portal:Linguistics/Featured article/23

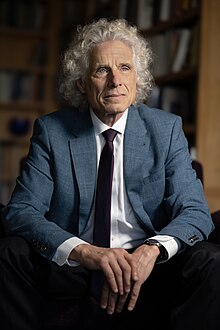

Steven Arthur Pinker (born September 18, 1954) is a Canadian-American cognitive psychologist, psycholinguist, popular science author, and public intellectual. He is an advocate of evolutionary psychology and the computational theory of mind.

Pinker is the Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology at Harvard University. He specializes in visual cognition and developmental linguistics, and his experimental topics include mental imagery, shape recognition, visual attention, regularity and irregularity in language, the neural basis of words and grammar, and childhood language development. Other experimental topics he works on are the psychology of cooperation and of communication, including emotional expression, euphemism, innuendo, and how people use "common knowledge", a term of art meaning the shared understanding in which two or more people know something, know that the other one knows, know the other one knows that they know, and so on. (Full article...)