Portal:Constructed languages/Selected language

Selected language items

[edit]To suggest an item, please do so here.

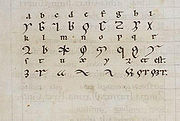

A Lingua Ignota (Latin for "unknown language") was described by the 12th century abbess of Rupertsberg, St. Hildegard of Bingen, OSB, who apparently used it for mystical purposes. To write it, she used an alphabet of 23 letters denominated litterae ignotae.

She partially described the language in a work titled Lingua Ignota per simplicem hominem Hildegardem prolata, which survived in two manuscripts, both dating to ca. 1200, the Wiesbaden Codex and a Berlin MS (Lat. Quart. 4º 674), previously Codex Cheltenhamensis 9303, collected by Sir Thomas Phillipps. The text is a glossary of 1011 words in Lingua Ignota, with glosses mostly in Latin, sometimes in German; the words appear to be a priori coinages, mostly nouns with a few adjectives. Grammatically it appears to be a partial relexification of Latin, that is, a language formed by substituting new vocabulary into an existing grammar.

The purpose of Lingua Ignota is unknown and it is not known who, besides its creator, was familiar with it. In the 19th century some believed that Hildegard intended her language to be an ideal, universal language. However, nowadays it is generally assumed that Lingua Ignota was devised as a secret language; like Hildegard's "unheard music", it would have come to her by divine inspiration. Inasmuch as the language was constructed by Hildegard, it may be considered one of the earliest known constructed languages. Find out more...

Novial [nov- ("new") + IAL, International Auxiliary Language] is a constructed international auxiliary language (IAL) for universal communication between speakers of different native languages. It was devised by Otto Jespersen, a Danish linguist who had been involved in the Ido movement, and later in the development of Interlingua de IALA. Its vocabulary is based largely on the Germanic and Romance languages and its grammar is influenced by English.

Novial was introduced in Jespersen's book An International Language in 1928. It was updated in his dictionary Novial Lexike in 1930, and further modifications were proposed in the 1930s, but the language became dormant with Jespersen's death in 1943. In the 1990s, with the revival of interest in constructed languages brought on by the Internet, some people rediscovered Novial.

Novial was first described in Jespersen’s book An International Language (1928). Part One of the book discusses the need for an IAL, the disadvantages of ethnic languages for that purpose, and common objections to constructed IALs. He also provides a critical overview of the history of constructed IALs with sections devoted to Volapük, Esperanto, Idiom Neutral, Ido, Latino sine Flexione and Occidental (Interlingue). The author makes it clear that he draws on a wealth of earlier work on the problem of a constructed IAL, not only the aforementioned IALs. Find out more...

Toki Pona is an oligoisolating constructed language, created by Canadian linguist and translator Sonja Lang as a philosophical language for the purpose of simplifying thoughts and communication. It was first published online in 2001 as a draft, and later in complete form in the book, Toki Pona: The Language of Good, in 2014. A small community of speakers developed in the early 2000s, and has continued to grow larger over the years, especially after the release of the official book. While, activity mostly takes place online in chat rooms, on social media, and in other groups, there have been a few organized in-person meetings in recent years.

The underlying feature of Toki Pona is minimalism. It focuses on simple universal concepts, making use of very little to express the most. The language has 120–125 root words and 14 phonemes that are easy to pronounce across different languages. Although not initially intended as an international auxiliary language, it may function as one. Inspired by Taoist philosophy, the language is designed to help users concentrate on basic things and to promote positive thinking, in accordance with the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis. Despite the small vocabulary, speakers are able to understand and communicate with each other, mainly relying on context and combinations of several words to express more specific meanings. Find out more...

Afrihili (Ni Afrihili Oluga 'the Afrihili language') is a constructed language designed in 1970 by Ghanaian historian K. A. Kumi Attobrah (Kumi Atɔbra) to be used as a lingua franca in all of Africa. The name of the language is a combination of Africa and Swahili. The author, a native of Akrokerri (Akrokɛri) in Ghana, originally conceived of the idea in 1967 while on a sea voyage from Dover to Calais. His intention was that "it would promote unity and understanding among the different peoples of the continent, reduce costs in printing due to translations and promote trade". It is meant to be easy for Africans to learn.

Afrihili draws its phonology, morphology and syntax from various African languages, particularly Swahili and Akan (Attobrah's native language). The lexicon covers various African languages, as well as words from many other sources "so Africanized that they do not appear foreign", although no specific etymologies are indicated by the author. However, the semantics is quite English, with many calques of English expressions, perhaps due to the strong English influence on written Swahili and Akan. For example, mu is 'in', to is 'to', and muto is 'into'; similarly, kupitia is 'through' (as in 'through this remedy'), paasa is 'out' (as in to go outside), and kupitia-paasa is 'throughout'—at least in the original, 1970 version of the language.

The language uses the Latin alphabet with the addition of two vowel letters, ⟨Ɛ ɛ⟩ and ⟨Ɔ ɔ⟩, which have their values in Ghanaian languages and the IPA, [ɛ] and [ɔ]. Find out more...

The Naʼvi language (Naʼvi: Lìʼfya leNaʼvi) is the constructed language of the Naʼvi, the sapient humanoid indigenous inhabitants of the fictional moon Pandora in the 2009 film Avatar. It was created by Paul Frommer, a professor at the USC Marshall School of Business with a doctorate in linguistics. Naʼvi was designed to fit James Cameron's conception of what the language should sound like in the film, to be realistically learnable by the fictional human characters of the film, and to be pronounceable by the actors, but to not closely resemble any single human language.

When the film was released in 2009, Naʼvi had a growing vocabulary of about a thousand words, but understanding of its grammar was limited to the language's creator. However, this has changed subsequently as Frommer has expanded the lexicon to more than 2200 words and has published the grammar, thus making Naʼvi a relatively complete, learnable and serviceable language.

The Naʼvi language has its origins in James Cameron's early work on Avatar. In 2005, while the film was still in scriptment form, Cameron felt it needed a complete, consistent language for the alien characters to speak. He had written approximately thirty words for this alien language but wanted a linguist to create the language in full. Find out more...

Interlingua (/ɪntərˈlɪŋɡwə/; ISO 639 language codes ia, ina) is an Italic international auxiliary language (IAL), developed between 1937 and 1951 by the International Auxiliary Language Association (IALA). It ranks among the top most widely used IALs (along with Esperanto and Ido), and is the most widely used naturalistic IAL: in other words, its vocabulary, grammar and other characteristics are derived from natural languages rather than a centrally planned grammar and vocabulary. Interlingua was developed to combine a simple, mostly regular grammar with a vocabulary common to the widest possible range of western European languages, making it unusually easy to learn, at least for those whose native languages were sources of Interlingua's vocabulary and grammar. Conversely, it is used as a rapid introduction to many natural languages. Interlingua literature maintains that (written) Interlingua is comprehensible to the hundreds of millions of people who speak Romance languages.

The name Interlingua comes from the Latin words inter, meaning between, and lingua, meaning tongue or language. These morphemes are identical in Interlingua. Thus, "Interlingua" would mean "between language". Find out more...

Europanto is a macaronic language concept with a fluid vocabulary from multiple European languages of the user's choice or need. It was conceived in 1996 by Diego Marani (a journalist, author and translator for the European Council of Ministers in Brussels) based on the common practice of word-borrowing usage of many EU languages. Marani used it in response to the perceived dominance of the English language; it is an emulation of the effect that non-native speakers struggling to learn a language typically add words and phrases from their native language to express their meanings clearly.

The main concept of Europanto is that there are no fixed rules—merely a set of suggestions. This means that anybody can start to speak Europanto immediately; on the other hand, it is the speaker's responsibility to draw on an assumed common vocabulary and grammar to communicate.

Marani wrote regular newspaper columns about the language and published a novel using it. As of 2005 he was no longer actively promoting it. Find out more...

Lojban (pronounced [ˈloʒban] ) is a constructed, syntactically unambiguous human language, succeeding the Loglan project.

The Logical Language Group (LLG) began developing Lojban in 1987. The LLG sought to realize Loglan's purposes, and further improve the language by making it more usable and freely available (as indicated by its official full English title, "Lojban: A Realization of Loglan"). After a long initial period of debating and testing, the baseline was completed in 1997, and published as The Complete Lojban Language. In an interview in 2010 with The New York Times, Arika Okrent, the author of In the Land of Invented Languages, stated: "The constructed language with the most complete grammar is probably Lojban—a language created to reflect the principles of logic."

Lojban is proposed as a speakable language for communication between people of different language backgrounds, as a potential means of machine translation and to explore the intersection of human language and software.

The name "Lojban" is a compound formed from loj and ban, which are short forms of logji (logic) and bangu (language). Find out more...

Esperanto (/ˌɛspəˈræntoʊ/ or /-ˈrɑː-/; ) is a constructed international auxiliary language. With an estimated two million speakers worldwide, it is the most widely spoken constructed language in the world. The Polish-Jewish ophthalmologist L. L. Zamenhof published the first book detailing Esperanto, Unua Libro, in Warsaw on July 26 [O.S. July 14] 1887. The name of Esperanto derives from Doktoro Esperanto (Esperanto translates as "one who hopes"), the pseudonym under which Zamenhof published Unua Libro. Zamenhof had three goals, as he wrote in Unua Libro:

- "To render the study of the language so easy as to make its acquisition mere play to the learner."

- "To enable the learner to make direct use of his knowledge with persons of any nationality, whether the language be universally accepted or not; in other words, the language is to be directly a means of international communication."

- "To find some means of overcoming the natural indifference of mankind, and disposing them, in the quickest manner possible, and en masse, to learn and use the proposed language as a living one, and not only in last extremities, and with the key at hand."

According to the database Ethnologue (published by the Summer Institute of Linguistics), up to two million people worldwide, to varying degrees, speak Esperanto, including about 1000 to 2000 native speakers who learned Esperanto from birth. Find out more...

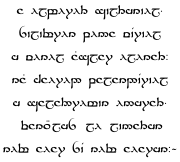

Sindarin is a fictional language devised by J. R. R. Tolkien for use in his fantasy stories set in Arda, primarily in Middle-earth. Sindarin is one of the many languages spoken by the immortal Elves, called the Eledhrim [ɛˈlɛðrim] or Edhellim [ɛˈðɛllim] in Sindarin. The word Sindarin is itself a Quenya form. The only known Sindarin word for this language is Eglathrin, a word probably only used in the First Age (see Eglath).

Called in English "Grey-elvish" or "Grey-elven", it was the language of the Sindarin Elves of Beleriand. These were Elves of the Third Clan who remained behind in Beleriand after the Great Journey. Their language became estranged from that of their kin who sailed over sea. Sindarin derives from an earlier language called Common Telerin, which evolved from Common Eldarin, the tongue of the Eldar before their divisions, e.g., those Elves who decided to follow the Vala Oromë and undertook the Great March to Valinor. Even before that the Eldar Elves spoke the original speech of all Elves, or Primitive Quendian.

In the Third Age (the setting of The Lord of the Rings), Sindarin was the language most commonly spoken by most Elves in the Western part of Middle-earth. Sindarin is the language usually referred to as the elf-tongue or elven-tongue in The Lord of the Rings. When the Quenya-speaking Noldor returned to Middle-earth, they adopted the Sindarin language. Quenya and Sindarin were related, with many cognate words but differing greatly in grammar and structure. Sindarin is said to be more changeful than Quenya, and there were during the First Age a number of regional dialects. Find out more...

Blissymbols or Blissymbolics was conceived as an ideographic writing system called Semantography consisting of several hundred basic symbols, each representing a concept, which can be composed together to generate new symbols that represent new concepts. Blissymbols differ from most of the world's major writing systems in that the characters do not correspond at all to the sounds of any spoken language.

Blissymbols was invented by Charles K. Bliss (1897–1985), born Karl Kasiel Blitz in the Austro-Hungarian city of Czernowitz (at present the Ukrainian city of Chernivtsi), which had a mixture of different nationalities that “hated each other, mainly because they spoke and thought in different languages.” Bliss graduated as a chemical engineer at the Vienna University of Technology, and joined an electronics company as a research chemist. As the German Army invaded Austria in 1938, Bliss, a Jew, was sent to the concentration camps of Dachau and Buchenwald. His German wife Claire managed to get him released, and they finally became exiles in Shanghai, where Bliss had a cousin. Bliss devised Blissymbols while a refugee at the Shanghai Ghetto and Sydney, from 1942 to 1949. He wanted to create an easy-to-learn international auxiliary language to allow communication between different linguistic communities. He was inspired by Chinese characters, with which he became familiar at Shanghai. Find out more...

Zaum (Russian: зáумь) are the linguistic experiments in sound symbolism and language creation of Russian-empire Futurist poets such as Velimir Khlebnikov and Aleksei Kruchenykh. Coined by Kruchenykh in 1913, the word zaum is made up of the Russian prefix за "beyond, behind" and noun ум "the mind, nous" and has been translated as "transreason", "transration" or "beyonsense" (Paul Schmidt). According to scholar Gerald Janecek, zaum can be defined as experimental poetic language characterized by indeterminacy in meaning.

Kruchenykh, in “Declaration of the Word as Such (1913),” declares zaum “a language which does not have any definite meaning, a transrational language” that “allows for fuller expression” whereas, he maintains, the common language of everyday speech “binds.” He further maintained, in “Declaration of Transrational Language (1921),” that zaum “can provide a universal poetic language, born organically, and not artificially, like Esperanto."

Examples of zaum include Kruchenykh's poem "Dyr bul shchyl", Kruchenykh's libretto for the Futurist opera Victory over the Sun with music by Mikhail Matyushin and stage design by Kazimir Malevich, and Khlebnikov's so-called "language of the birds", "language of the gods" and "language of the stars". The poetic output is perhaps comparable to that of the contemporary Dadaism but the linguistic theory or metaphysics behind zaum was entirely devoid of the gentle self-irony of that movement and in all seriousness intended to recover the sound symbolism of a lost aboriginal tongue. Find out more...

The Latin term characteristica universalis, commonly interpreted as universal characteristic, or universal character in English, is a universal and formal language imagined by the German polymathic genius, mathematician, scientist and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz able to express mathematical, scientific, and metaphysical concepts. Leibniz thus hoped to create a language usable within the framework of a universal logical calculation or calculus ratiocinator. The characteristica universalis is a recurring concept in the writings of Leibniz. When writing in French, he sometimes employed the phrase spécieuse générale to the same effect. The concept is sometimes paired with his notion of a calculus ratiocinator and with his plans for an encyclopaedia as a compendium of all human knowledge.

Many Leibniz scholars writing in English seem to agree that he intended his characteristica universalis or "universal character" to be a form of pasigraphy, or ideographic language. This was to be based on a rationalised version of the 'principles' of Chinese characters, as Europeans understood these characters in the seventeenth century. From this perspective it is common to find the characteristica universalis associated with contemporary universal language projects like Esperanto, auxiliary languages like Interlingua, and formal logic projects like Frege's Begriffsschrift. The global expansion of European commerce in Leibniz's time provided mercantilist motivations for a universal language of trade so that traders could communicate with any natural language. Find out more...

Neo is an artificially constructed international auxiliary language created by Arturo Alfandari, a Belgian diplomat of Italian descent. The language combines features of Esperanto, Ido, Novial and Volapük. The root base of the language and grammar (in contrast to that of Esperanto and Ido) are closely related to that of the French language, with some English influences.

The first Neo draft was published in 1937 by Arturo Alfandari but attracted wider attention in 1961 when Alfandari published his books Cours Pratique de Neo and The Rapid Method of Neo. The works included both brief and complete grammar, learning course of 44 lectures, translations of literary works (poetry and prose), original Neo literature, scientific and technical texts, idioms, detailed bidirectional French and English dictionaries. The total volume of the publications was 1304 pages, with dictionaries numbering some 75 000 words. Such a degree of details was unprecedented among constructed languages of the time.

The language stands in the tradition of international auxiliary languages such as Esperanto or Ido, with the same goal: a simple, neutral and easy to learn second language for everybody. Neo attracted the interest of the circle around the International Language Review, a periodical for IAL proponents whose publishers co-founded the international Friends of Neo (Amikos de Neo) with Alfandari; the organization also published its bulletin, the Neo-bulten. For a few years it looked like Neo could give some serious competition to Esperanto and Interlingua. Find out more...

The Valyrian languages are a fictional language family in the A Song of Ice and Fire series of fantasy novels by George R. R. Martin, and in their television adaptation Game of Thrones.

In the novels, High Valyrian and its descendant languages are often mentioned, but not developed beyond a few words. For the TV series, linguist David J. Peterson created the High Valyrian language, as well as the derivative languages Astapori and Meereenese Valyrian, based on the fragments given in the novels. Valyrian, alongside Dothraki, has been described as "the most convincing fictional tongues since Elvish".

In the world of A Song of Ice and Fire, High Valyrian occupies a cultural niche similar to that of Latin in medieval Europe. The novels describe it as no longer being used as a language of everyday communication, but rather as a language of learning and education among the nobility of Essos and Westeros, with much literature and song composed in Valyrian.

To create the Dothraki and Valyrian languages to be spoken in Game of Thrones, HBO selected the linguist David J. Peterson through a competition among conlangers. The producers gave Peterson a largely free hand in developing the languages, as, according to Peterson, George R. R. Martin himself was not very interested in the linguistic aspect of his works. The already published novels include only a few words of High Valyrian, including valar morghulis ("all men must die"), valar dohaeris ("all men must serve") and dracarys ("dragonfire"). Find out more...

Interslavic (Medžuslovjansky, in Cyrillic Меджусловјанскы) is a zonal auxiliary language based on the Slavic languages. Its purpose is to facilitate communication between representatives of different Slavic nations, as well as to allow people who do not know any Slavic language to communicate with Slavs. For the latter, it can fulfill an educational role as well.

Interslavic can be classified as a semi-constructed language. It is essentially a modern continuation of Old Church Slavonic, but also draws on the various improvised language forms Slavs have been using for centuries to communicate with Slavs of other nationalities, for example in multi-Slavic environments and on the Internet, providing them with a scientific base. Thus, both grammar and vocabulary are based on the commonalities between the Slavic languages, and non-Slavic elements are avoided. Its main focus lies on instant understandability rather than easy learning, a balance typical for naturalistic (as opposed to schematic) languages.

The language has a long history, predating constructed languages like Volapük and Esperanto by centuries: the oldest description, written by the Croatian priest Juraj Križanić, goes back to the years 1659–1666. In its current form, Interslavic was created in 2006 under the name Slovianski. In 2011, Slovianski underwent a thorough reform and merged with two other projects, simultaneously changing its name to "Interslavic", a name that was first proposed by the Czech Ignac Hošek in 1908.

Interslavic can be written using the Latin and the Cyrillic alphabets. Find out more...

Khuzdul is a constructed language devised by J. R. R. Tolkien. It is one of the many fictional languages set in Middle-earth. It was the secret language of the Dwarves.

Tolkien noted some similarities between Dwarves and Jews: both were "at once natives and aliens in their habitations, speaking the languages of the country, but with an accent due to their own private tongue…". Tolkien also commented of the Dwarves that "their words are Semitic obviously, constructed to be Semitic." Tolkien based Khuzdul on Semitic languages. Like these, Khuzdul has triconsonantal roots: √KhZD "dwarf", √BND "head", √ZGL "silver (colour)". Also other similarities to Hebrew in phonology and morphology have been observed. Although only a very limited vocabulary is known, Tolkien mentioned that he had developed the language to a certain extent. A small amount of material on Khuzdul phonology and root modifications has survived and will be published in the future.

In the fictional setting of Middle-earth, little is known of Khuzdul (once written Khuzdûl), the Dwarves kept it secret, except for place names and a few phrases such as their battle-cry: Baruk Khazâd! Khazâd ai-mênu! meaning Axes of the Dwarves! The Dwarves are upon you! Find out more...

Basic English is an English-based controlled language created by linguist and philosopher Charles Kay Ogden as an international auxiliary language, and as an aid for teaching English as a second language. Basic English is, in essence, a simplified subset of regular English. It was presented in Ogden's book Basic English: A General Introduction with Rules and Grammar (1930).

Ogden's Basic, and the concept of a simplified English, gained its greatest publicity just after the Allied victory in World War II as a means for world peace. Although Basic English was not built into a program, similar simplifications have been devised for various international uses. Ogden's associate I. A. Richards promoted its use in schools in China. More recently, it has influenced the creation of Voice of America's Special English for news broadcasting, and Simplified Technical English, another English-based controlled language designed to write technical manuals. What survives today of Ogden's Basic English is the basic 850-word list used as the beginner's vocabulary of the English language taught worldwide, especially in Asia.

Ogden tried to simplify English while keeping it normal for native speakers, by specifying grammar restrictions and a controlled small vocabulary which makes an extensive use of paraphrasing. Most notably, Ogden allowed only 18 verbs, which he called "operators". His General Introduction says "There are no 'verbs' in Basic English", with the underlying assumption that, as noun use in English is very straightforward but verb use/conjugation is not, the elimination of verbs would be a welcome simplification. Find out more...

Brithenig is an invented language, or constructed language ("conlang"). It was created as a hobby in 1996 by Andrew Smith from New Zealand, who also invented the alternate history of Ill Bethisad to "explain" it.

Brithenig was not developed to be used in the real world, like Esperanto or Interlingua, nor to provide detail to a work of fiction, like Klingon from the Star Trek scenarios. Rather, Brithenig started as a thought experiment to create a Romance language that might have evolved if Latin had displaced the native Celtic language as the spoken language of the people in Great Britain. The result is an artificial sister language to French, Catalan, Spanish, Portuguese, Romanian, Occitan and Italian which differs from them by having sound-changes similar to those that affected the Welsh language, and words that are borrowed from the Brittonic languages and from English throughout its pseudo-history. One important distinction between Brithenig and Welsh is that while Welsh is P-Celtic, Latin was a Q-Italic language (as opposed to P-Italic, like Oscan), and this trait was passed onto Brithenig.

Similar efforts to extrapolate Romance languages are Breathanach (influenced by the other branch of Celtic), Judajca (influenced by Hebrew), Þrjótrunn (a non-Ill Bethisad language influenced by Icelandic), Wenedyk (influenced by Polish), and Xliponian (which experienced a Grimm's law-like sound shift). It has also inspired Wessisc, a hypothetical Germanic language influenced by contact with Old Celtic. Find out more...

The language Occidental, later Interlingue, is a planned international auxiliary language created by the Balto-German naval officer and teacher Edgar de Wahl, and published in 1922. The vocabulary is based on already existing words from various languages. The language is thereby naturalistic, at the same time as it is constructed to be regular. Occidental was quite popular in the years before the Second World War, but declined in the years thereafter.

Occidental is devised so that many of its derived word forms reflect the similar forms common to a number of Western European languages, primarily those in the Romance family. This was done through application of De Wahl's rule which is a set of rules for converting verb infinitives into derived nouns and adjectives. The result is a language easy to understand at first sight for individuals acquainted with several Western European languages. Coupled with a simplified grammar, this made Occidental exceptionally popular in Europe during the 15 years before World War II.

In The Esperanto Book, Don Harlow says that Occidental had an intentional emphasis on European forms, and that some of its leading followers espoused a Eurocentric philosophy, which may have hindered its spread. Still, Occidental gained adherents in many nations including Asian nations. According to the Occidental magazine Cosmoglotta in 1928, a majority of Ido adherents took up Occidental in place of Ido. Find out more...

Ithkuil is an experimental constructed language created by John Quijada, designed to express deeper levels of human cognition briefly yet overtly and clearly, particularly with regard to human categorization. Presented as a cross between an a priori philosophical and a logical language striving to minimize the ambiguities and semantic vagueness found in natural human languages, Ithkuil is notable for its grammatical complexity and extensive phoneme inventory, the latter being simplified in the final version of the language. The name "Ithkuil" is an anglicized form of Iţkuîl, which in the original form roughly means "hypothetical representation of a language". Quijada states he did not create Ithkuil to be auxiliary or used in everyday conversations, but rather to serve as a language for more elaborate and profound fields where more insightful thoughts are expected, such as philosophy, arts, science and politics.

The many examples from the original grammar book show that a message, like a meaningful phrase or a sentence, can usually be expressed in Ithkuil with fewer sounds, or lexically distinct speech-elements, than in natural human languages. For example, the two-word Ithkuil sentence "Tram-mļöi hhâsmařpţuktôx" can be translated into English as "On the contrary, I think it may turn out that this rugged mountain range trails off at some point". Quijada deems his creation too complex and strictly regular a language to have developed naturally, but nonetheless a language suited to human conversation. No person, including Quijada, is known to be able to speak Ithkuil fluently.

Three versions of the language have been publicized: the initial version in 2004, a revised version called Ilaksh in 2007, and a final, definitive version in 2011. Find out more...

Volapük (/ˈvɒləpʊk/ in English; [volaˈpyk] in Volapük) is a constructed language, created in 1879 and 1880 by Johann Martin Schleyer, a Roman Catholic priest in Baden, Germany. Schleyer felt that God had told him in a dream to create an international language. Volapük conventions took place in 1884 (Friedrichshafen), 1887 (Munich) and 1889 (Paris). The first two conventions used German, and the last conference used only Volapük. In 1889, there were an estimated 283 clubs, 25 periodicals in or about Volapük, and 316 textbooks in 25 languages; at that time the language claimed nearly a million adherents. Volapük was largely displaced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by Esperanto.

Schleyer first published a sketch of Volapük in May 1879 in Sionsharfe, a Catholic poetry magazine of which he was editor. This was followed in 1880 by a full-length book in German. Schleyer himself did not write books on Volapük in other languages, but other authors soon did.

André Cherpillod writes of the third Volapük convention: "In August 1889 the third convention was held in Paris. About two hundred people from many countries attended. And, unlike in the first two conventions, people spoke only Volapük. For the first time in the history of mankind, sixteen years before the Boulogne convention, an international convention spoke an international language." Find out more...

Newspeak is the language of Oceania, a fictional totalitarian state ruled by the Party, who created the language to meet the ideological requirements of English Socialism (Ingsoc). In the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), Newspeak is a controlled language, of restricted grammar and limited vocabulary, a linguistic design meant to limit the freedom of thought—personal identity, self-expression, free will—that ideologically threatens the régime of Big Brother and the Party, who thus criminalized such concepts as thoughtcrime, contradictions of Ingsoc orthodoxy.

In "The Principles of Newspeak", the appendix to the novel, George Orwell explains that Newspeak usage follows most of the English grammar, yet is a language characterised by a continually diminishing vocabulary; complete thoughts reduced to simple terms of simplistic meaning. Linguistically, the contractions of Newspeak—Ingsoc (English Socialism), Minitrue (Ministry of Truth), etc.—derive from the syllabic abbreviations of Russian, which identify the government and social institutions of the Soviet Union, such as politburo (Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union), Comintern (Communist International), kolkhoz (collective farm), and Komsomol (Young Communists' League). The long-term political purpose of the new language is for every member of the Party and society, except the Proles—the working-class of Oceania—to exclusively communicate in Newspeak, by the year A.D. 2050; during that 66-year transition, the usage of Oldspeak (Standard English) shall remain interspersed among Newspeak conversations.

Newspeak is also a constructed language, of planned phonology, grammar, and vocabulary, like Basic English, which Orwell promoted (1942–44) during the Second World War (1939–45), and later rejected in the essay "Politics and the English Language" (1946), wherein he criticises the bad usage of English in his day. Find out more...

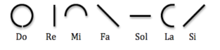

Solresol (Solfège: Sol-Re-Sol) is a constructed language devised by François Sudre, beginning in 1827. His major book on it, Langue musicale universelle, was published after his death in 1866, though he had already been publicizing it for some years. Solresol enjoyed a brief spell of popularity, reaching its pinnacle with Boleslas Gajewski's 1902 posthumous publication of Grammaire du Solresol. An ISO 639-3 language code has been requested as of 28 July 2017.

The teaching of sign languages to the deaf was discouraged between 1880 and 1991 in France, contributing to Solresol's descent into obscurity. After a few years of popularity, Solresol nearly vanished in the face of more successful languages, such as Volapük and Esperanto. Today, there exist small communities of Solresol enthusiasts scattered across the world, able to communicate with one another due to the internet.

Solresol words are made from one to five syllables or notes. Each of these may be one of only seven basic phonemes, which may in turn be accented or lengthened. There is another phoneme, silence, which is used to separate words: words cannot be run together as they are in English.

The phonemes can be represented in a number of different ways – as the seven musical notes in an octave, as spoken syllables (based on solfège, a way of identifying musical notes), with the seven colors of the rainbow, symbols, hand gestures etc. Thus, theoretically Solresol communication can be done through speaking, singing, signing, flags of different color – even painting. Find out more...

Tsolyáni is one of several languages invented by M. A. R. Barker, developed in the mid-to-late 1940s in parallel with his legendarium leading to the world of Tékumel as described in the Empire of the Petal Throne roleplaying game, published by TSR in 1975. It was the first constructed language ever published as part of a role-playing game and draws its inspiration from Urdu, Pashto, Mayan and Nahuatl. The last influence can be seen in the inclusion of the sounds hl [ɬ] and tl [tɬ]. One exact borrowing from a real-world source is the Tsolyáni noun root sákbe, referring to the fortified highways of the Five Empires; it is the same word as the Yucatec Maya sacbe, referring to the raised paved roads constructed by the pre-Columbian Maya. Another close borrowing is from the Nahuatl word tlatoani, referring to a leader of an Aztec state (e.g. Montezuma); it is similar to the clan-name of the Tsolyáni emperors, Tlakotáni.

Tsolyáni is written in an offshoot of the Engsvanyáli script which was developed by Barker in parallel with the language, being very close to its modern-day form by 1950. It is read from right-to-left and is constructed like the Arabic script. The consonants each have 4 different forms: isolate, initial, medial, and final; the 6 vowels and 3 diphthongs each only have an independent initial form, while diacritical marks are used for medial and final vowels. Find out more...

Ido /ˈiːdoʊ/ is a constructed language, derived from Reformed Esperanto, created to be a universal second language for speakers of diverse backgrounds. Ido was specifically designed to be grammatically, orthographically, and lexicographically regular, and above all easy to learn and use. In this sense, Ido is classified as a constructed international auxiliary language. It is the most successful of many Esperanto derivatives, called Esperantidos.

Ido was created in 1907 out of a desire to reform perceived flaws in Esperanto, a language that had been created 20 years earlier to facilitate international communication. The name of the language traces its origin to the Esperanto word ido, meaning "offspring", since the language is a "descendant" of Esperanto. After its inception, Ido gained support from some in the Esperanto community, but following the sudden death in 1914 of one of its most influential proponents, Louis Couturat, it declined in popularity. There were two reasons for this: first, the emergence of further schisms arising from competing reform projects; and second, a general lack of awareness of Ido as a candidate for an international language. These obstacles weakened the movement and it was not until the rise of the Internet that it began to regain momentum.

Ido uses the same 26 letters as the English (Latin) alphabet, with no diacritics. It draws its vocabulary from English, French, German, Italian, Latin, Russian, and Spanish, and is largely intelligible to those who have studied Esperanto. Several works of literature have been translated into Ido, including The Little Prince and the Gospel of Luke. As of the year 2000, there were approximately 100–200 Ido speakers in the world. Find out more...

Quenya (pronounced [ˈkʷwɛnja] is a fictional language devised by J. R. R. Tolkien and used by the Elves in his legendarium. Tolkien began devising the language around 1910 and restructured the grammar several times until Quenya reached its final state. The vocabulary remained relatively stable throughout the creation process. Also, the name of the language was repeatedly changed by Tolkien from Elfin and Qenya to the eventual Quenya. The Finnish language had been a major source of inspiration, but Tolkien was also familiar with Latin, Greek, and ancient Germanic languages when he began constructing Quenya.

Another notable feature of Tolkien's Elvish languages was his development of a complex internal history of characters to speak those tongues in their own fictional universe. He felt that his languages changed and developed over time, as with the historical languages which he studied professionally—not in a vacuum, but as a result of the migrations and interactions of the peoples who spoke them. Within Tolkien's legendarium, Quenya is one of the many Elvish languages spoken by the immortal Elves, called Quendi ('speakers') in Quenya. Quenya translates as simply "language" or, in contrast to other tongues that the Elves met later in their long history, "elf-language". After the Elves divided, Quenya originated as the speech of two clans of "High Elves" or Eldar, the Noldor and the Vanyar, who left Middle-earth to live in Eldamar ("Elvenhome"), in Valinor, the land of the immortal and God-like Valar. Of these two groups of Elves, the Noldor returned to Middle-earth where they met the Sindarin-speaking Grey-elves. The Noldor eventually adopted Sindarin and used Quenya primarily as a ritual or poetic language, whereas the Vanyar who stayed behind in Eldamar retained the use of Quenya. Find out more...

Loglan is a constructed language originally designed for linguistic research, particularly for investigating the Sapir–Whorf Hypothesis. The language was developed beginning in 1955 by Dr James Cooke Brown with the goal of making a language so different from natural languages that people learning it would think in a different way if the hypothesis were true. In 1960 Scientific American published an article introducing the language. Loglan is the first among, and the main inspiration for, the languages known as logical languages, which also includes Lojban.

Brown founded The Loglan Institute (TLI) to develop the language and other applications of it. He always considered the language an incomplete research project, and although he released many papers about its design, he continued to claim legal restrictions on its use. Because of this, a group of his followers later formed the Logical Language Group to create the language Lojban along the same principles, but with the intention to make it freely available and encourage its use as a real language. Supporters of Lojban use the term Loglan as a generic term to refer to both their own language, and Brown's Loglan, referred to as "TLI Loglan" when in need of disambiguation. Although the non-trademarkability of the term Loglan was eventually upheld by the United States Patent and Trademark Office, many supporters and members of The Loglan Institute find this usage offensive, and reserve Loglan for the TLI version of the language.

Loglan (an abbreviation for "logical language") was created to investigate whether people speaking a "logical language" would in some way think more logically, as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis might predict. The language's grammar is based on predicate logic. The grammar was intended to be small enough to be teachable and manageable, yet complex enough to allow people to think and converse in the language. Find out more...

Lingua Franca Nova (or Elefen) is an auxiliary constructed language originally created by C. George Boeree of Shippensburg University, Pennsylvania. Its vocabulary is based on the Romance languages French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Catalan. The grammar is highly reduced and similar to the Romance creoles. The language has phonemic spelling, using 22 letters of either the Latin or Cyrillic scripts.

Boeree was inspired by the Mediterranean Lingua Franca, a pidgin used in the Mediterranean in centuries past, and by creoles such as Papiamento, Haitian Creole, and Bislama. He used French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Catalan as the basis for his new language.

LFN was first presented on the Internet in 1998. A Yahoo! Group was formed in 2002 by Bjorn Madsen. Group members contributed significantly to the further evolution of the language. In 2007, Igor Vasiljevic began a Facebook page, which has over 300 members. LFN was given an ISO 639-3 designation (lfn) by SIL in 2008. Find out more...

Wenedyk (English: Venedic) is a naturalistic constructed language, created by the Dutch translator Jan van Steenbergen (who also co-created the international auxiliary language Interslavic). It is used in the fictional Republic of the Two Crowns (based on the Republic of Two Nations), in the alternate timeline of Ill Bethisad. Officially, Wenedyk is a descendant of Vulgar Latin with a strong Slavic admixture, based on the premise that the Roman Empire incorporated the ancestors of the Poles in their territory. Less officially, it tries to show what Polish would have looked like if it had been a Romance instead of a Slavic language. On the Internet, it is well-recognized as an example of the altlang genre, much like Brithenig and Breathanach.

The idea for the language was inspired by such languages as Brithenig and Breathanach, languages that bear a similar relationship to the Celtic languages as Wenedyk does to Polish. The language itself is based entirely on (Vulgar) Latin and Polish: all phonological, morphological, and syntactic changes that made Polish develop from Common Slavic are applied to Vulgar Latin. As a result, vocabulary and morphology are predominantly Romance in nature, whereas phonology, orthography and syntax are essentially the same as in Polish. Wenedyk uses the modern standard Polish orthography, including (for instance) ⟨w⟩ for /v/ and ⟨ł⟩ for /w/. Find out more...

Sambahsa or Sambahsa-Mundialect is an international auxiliary language (IAL) devised by French Dr. Olivier Simon. Among IALs it is categorized as a worldlang. It is based on the Proto Indo-European language (PIE), with a highly simplified grammar. The language was first released on the Internet in July 2007; prior to that, the creator claims to have worked on it for eight years. According to one of the rare academic studies addressing recent auxiliary languages, "Sambahsa has an extensive vocabulary and a large amount of learning and reference material".

The first part of the name of the language, Sambahsa, is taken from two Malay words, sama and bahsa, which mean 'same' and 'language' respectively. Mundialect, on the other hand, is a result of combining two Romance words: mondial (worldwide) and dialect (dialect).

Sambahsa tries to preserve the original spellings of words as much as possible and this makes its orthography complex, though still kept regular. There are four grammatical cases: nominative, accusative, dative and genitive.

Sambahsa, though based on PIE, borrows a good proportion of its vocabulary from languages such as Arabic, Chinese, Indonesian, Swahili and Turkish, which belong to various other language families. Find out more...