Post-war immigration to Australia

Post-war immigration to Australia deals with migration to Australia in the decades immediately following World War II, and in particular refers to the predominantly European wave of immigration which occurred between 1945 and the end of the White Australia policy in 1973. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Ben Chifley, Prime Minister of Australia (1945–1949), established the federal Department of Immigration to administer a large-scale immigration program. Chifley commissioned a report on the subject which found that Australia was in urgent need of a larger population for the purposes of defence and development and it recommended a 1% annual increase in population through increased immigration.[1]

The first Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, promoted mass immigration with the slogan "populate or perish".[2] It was Billy Hughes, as Minister for Health and Repatriation, who had coined the "populate or perish" slogan in the 1930s.[3] Calwell coined the term "New Australians" in an effort to supplant such terms as Balt, pommy and wog.

The 1% target remained a part of government policy until the Whitlam government (1972–1975), when immigration numbers were substantially cut back, only to be restored by the Fraser government (1975–1982).[1]

Some 4.2 million immigrants arrived between 1945 and 1985, about 40 percent of whom came from Britain and Ireland.[4][full citation needed] 182,159 people were sponsored by the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) from the end of World War II up to the end of 1954 to resettle in Australia from Europe—more than the number of convicts transported to Australia in the first 80 years after European settlement.[5]

"Populate or perish" policy

[edit]The Chifley years

[edit]

Following the attacks on Darwin and the associated fear of Imperial Japanese invasion in World War II, the Chifley government commissioned a report on the subject which found that Australia was in urgent need of a larger population for the purposes of defence and development and it recommended a 1% annual increase in population through increased immigration.[1] In 1945, the government established the federal Department of Immigration to administer the new immigration program. The first Minister for Immigration was Arthur Calwell. An Assisted Passage Migration Scheme was also established in 1945 to encourage Britons to migrate to Australia. The government's objective was summarised in the slogan "populate or perish". Calwell stated in 1947, to critics of mass immigration from non-British Europe: "We have 25 years at most to populate this country before the yellow races are down on us."

The post-war immigration program of the Chifley government gave them preference to migrants from Great Britain, and initially an ambitious target was set of nine British out of ten immigrants.[1] However, it was soon apparent that even with assisted passage the government target would be impossible to achieve given that Britain's shipping capacity was quite diminished from pre-war levels. As a consequence, the government looked further afield to maintain overall immigration numbers, and this meant relying on the IRO refugees from Eastern Europe, with the US providing the necessary shipping.[1][6] Many Eastern Europeans were refugees from the Red Army and thus mostly anti-Communist and so politically acceptable.[7]

Menzies years

[edit]

The 1% target survived a change of government in 1949, when the Menzies government succeeded Chifley's. The new Minister of Immigration was Harold Holt (1949–56).

The British component remained the largest component of the migrant intake until 1953.[1] Between 1953 and late 1956, migrants from Southern Europe outnumbered the British, and this caused some alarm in the Australian government, causing it to place restrictions on Southern Europeans sponsoring newcomers and to commence the "Bring out a Briton" campaign. With the increase in financial assistance to British settlers provided during the 1960s, the British component was able to return to the top position in the overall number of new settlers.[8]

Hundreds of thousands of displaced Europeans migrated to Australia and over 1,000,000 Britons immigrated with financial assistance.[9] The migration assistance scheme initially targeted citizens of Commonwealth countries; but it was gradually extended to other countries such as the Netherlands and Italy. The qualifications were straightforward: migrants needed to be in sound health and under the age of 45 years. There were initially no skill requirements, although under the White Australia policy, people from mixed-race backgrounds found it very difficult to take advantage of the scheme.[10]

Migration brought large numbers of southern and central Europeans to Australia for the first time. A 1958 government leaflet assured voters that unskilled non-British migrants were needed for "labour on rugged projects ...work which is not generally acceptable to Australians or British workers."[11][full citation needed] The Australian economy stood in sharp contrast to war-ravaged Europe, and newly arrived migrants found employment in a booming manufacturing industry and government assisted programmes such as the Snowy Mountains Scheme. This hydroelectricity and irrigation complex in south-east Australia consisted of sixteen major dams and seven power stations constructed between 1949 and 1974. It remains the largest engineering project undertaken in Australia. Necessitating the employment of 100,000 people from over 30 countries, to many it denotes the birth of multicultural Australia.[12]

In 1955 the one-millionth post-war immigrant arrived in Australia. Australia's population reached 10 million in 1959, up from 7 million in 1945.

End to the White Australia policy

[edit]In 1973, Whitlam government (1972–1975) adopted a completely non-discriminatory immigration policy, effectively putting an end to the White Australia policy. However, the change occurred in the context of a substantial reduction in the overall migrant intake. This ended the post-war wave of predominantly European immigration which had started three decades before with the end of the Second World War and would make the beginnings of the contemporary wave of predominantly Asian Immigration to Australia which continues to the present day.

International agreements

[edit]Financial assistance was an important element of the post war immigration program and as such there were a number of agreements in place between the Australian government and various governments and international organisations.[13]

- United Kingdom – free or assisted passages.[13] Immigrants under this scheme became known as Ten Pound Poms.

- Assisted passages for ex-servicemen of the British Empire and the United States.[13] This scheme was later extended to cover ex-servicemen and members of resistance movements from certain other Allied countries.[13]

- An agreement with the International Refugee Organization (IRO) to settle at least 12,000 displaced people a year from camps in Europe.[13] Australia accepted a disproportionate share of refugees sponsored by IRO in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[14]

- Formal migration agreements, often involving the grant of assisted passage, with the United Kingdom, Malta, the Netherlands, Italy, West Germany, Turkey and Yugoslavia.[13]

- There were also informal migration agreements with a number of other countries including Austria, Greece, Spain, and Belgium.[13]

Timeline

[edit]| Period | Events |

|---|---|

| 1947 | Australia's first migrant reception centre opened at Bonegilla, Victoria – the first assisted migrants were received there in 1951.[15] |

| 1948 | Australia signed Peace treaties with Italy, Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary and accepted immigrants from these countries.[2] |

| 1949 | In 1949 assisted arrivals reached more than 118,800, four times the 1948 figure.[2]

In August Australia welcomed its 50,000th "New Australian" — or rather, the 50,000th displaced person sponsored by the IRO and to be resettled in Australia. The child was from Riga, Latvia.[14][16] Work began on the Snowy Mountains Scheme – a substantial employer of migrants: 100,000 people were employed from at least 30 different nationalities. Seventy percent of all the workers were migrants.[12] |

| 1950 | Net Overseas Migration was 153,685, the third highest figure of the twentieth century.[2][a] |

| 1951 | The first assisted migrants received at the Bonegilla Migrant Reception and Training Centre.[15] By 1951, the government had established three migrant reception centres for non-English speaking displaced persons from Europe, and twenty holding centres, principally to house non-working dependants, when the pressure of arrival numbers on the reception centres was too great to keep families together.[15] |

| 1952 | The IRO was abolished and from then most refugees who resettled in Australia during the 1950s were brought here under the auspices of the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (ICEM).[14] |

| 1954 | The 50,000th Dutch migrant arrived.[17] |

| 1955 | Australia's millionth post-war immigrant arrived.[2] She was a 21-year-old from the United Kingdom and newly married.[18][19][20] |

| 1971 | Migrant camp at Bonegilla, Victoria closed – some 300,000 migrants had spent time there.[15] |

Settler arrivals by top 10 countries of birth

[edit]| Birthplace | July 1949 – June 1959[21][b] | July 1959 – June 1970[c] | July 1970 – June 1980 |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom & Ireland | 419,946 (33.5%) | 654,640 (45.3%) | 342,373 (35.8%) |

| Italy | 201,428 (16.1%) | 150,669 (10.4%) | 28,800 (3.0%) |

| New Zealand | 29,649 (2.4%) | 30,341 (2.1%) | 58,163 (6.1%) |

| Germany | 162,756 (13.0%) | 50,452 (3.5%) | not in top 10 |

| Greece | 55,326 (4.4%) | 124,324 (8.6%) | 30,907 (3.2%) |

| Yugoslavia[d] | not in top 10 | 94,555 (6.5%) | 61,283 (6.4%) |

| Netherlands | 100,970 (8.1%) | 36,533 (2.5%) | not in top 10 |

| Malta | 38,113 (3.0%) | 28,916 (2.0%) | not in top 10 |

| US | 16,982 (1.4%) | 20,467 (1.4%) | 27,769 (2.9%) |

| Spain | not in top 10 | 17,611 (1.2%) | not in top 10 |

| Total settler arrivals | 1,253,083 | 1,445,356 | 956,769 |

Migrant reception and training centres

[edit]

On arrival in Australia, many migrants went to migrant reception and training centres where they learned some English while they looked for a job. The Department of Immigration was responsible for the camps and kept records on camp administration and residents.[22] The migrant reception and training centres were also known as Commonwealth Immigration Camps, migrant hostels, immigration dependants' holding centres, migrant accommodation, or migrant workers' hostels.[23][24]

Australia's first migrant reception centre opened at Bonegilla, Victoria near Wodonga in December 1947. When the camp closed in 1971, some 300,000 migrants had spent time there.[15]

By 1951, the government had established three migrant reception centres for non-English speaking displaced persons from Europe, and twenty holding centres, principally to house non-working dependants, when the pressure of arrival numbers on the reception centres was too great to keep families together.[15] The purpose of reception and training centres was to:

provide for general medical examination and x-ray of migrants, issue of necessary clothing, payment of social service benefits, interview to determine employment potential, instruction in English and the Australian way of life generally.[15]

The centres were located throughout Australia (dates are those of post office opening and closing.[25])

Queensland

[edit]- Stuart[22]

- Wacol[22]

- Yungaba Immigration Centre (known today as Yungaba House)

New South Wales (NSW)

[edit]- Bathurst (1948 to 1952)[26]

- Bradfield Park, now Lindfield[23]

- Chullora, a suburb of Sydney (1 August 1949 to 31 October 1967)

- Greta, near Newcastle (1 June 1949 to 15 January 1960)

- Uranquinty (1 December 1948 to 31 March 1959)

Other hostels in New South Wales included Adamstown, Balgownie, Bankstown, Berkeley, Bunnerong, Burwood, Cabramatta, Cronulla, Dundas, East Hills, Ermington, Goulburn, Katoomba, Kingsgrove, Kyeemagh, Leeton, Lithgow, Mascot, Matraville, Mayfield, Meadowbank, Nelson Bay, North Head, Orange, Parkes, Port Stephens, Randwick, St Marys, Scheyville, Schofields, Unanderra, Villawood, Wallerawang and Wallgrove.[24]

Victoria

[edit]- Bonegilla (December 1947 to 17 March 1971)

- Benalla (9 June 1949 to 30 May 1952)

- Mildura (1950 to 17 July 1953)

- Rushworth (1 June 1949 to 15 June 1953)

- Sale West (1950 to 30 November 1953)

- Somers (18 August 1949 to 14 February 1957)

- Fishermans Bend (1952)

South Australia

[edit]Western Australia

[edit]- Northam Holden (15 August 1949 to 30 June 1957)

- Graylands[22]

- Cunderdin[22]

- Point Walter[27]

Breakdown of arrivals by decade

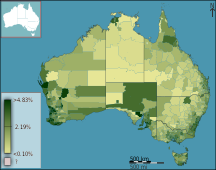

[edit]- Immigrants who arrived in Australia (by decade of arrival) as a percentage of the total population, subdivided geographically by statistical local area, as of the 2011 census

-

1941–1950

-

1951–1960

-

1961–1970

-

1971–1980

In the post-war wave of immigration Australia has experienced average arrivals of around one million per decade. The breakdown by decade is as follows:

- 1.6 million between October 1945 and 30 June 1960;

- about 1.3 million in the 1960s; and

- about 960.000 in the 1970s;

The highest number of arrivals during the period was 185,099 in 1969–70 and the lowest was 52,752 in 1975–76.[citation needed]

2006 demographics of post-war period non-English speaking immigrant groups

[edit]In the 2006 census, birthplace was enumerated as was date of arrival in Australia for those not born in Australia. For the major post-war period non-English speaking immigrant groups enlarged by the arrival of immigrants to Australia after World War II, they are still major demographic groups in Australia:

| Ethnic group | Persons born overseas[28] | Arrived 1979 or earlier[28] | Aged 60 years and over[28]

This compares with 18% of Australian residents |

Australian citizens[28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian Australian | 199,124 | 176,536 or 89% | 63% | 157,209 or 79% |

| Greek Australian | 109,990 | 94,766 or 86% | 60% | 104,950 or 95% |

| German Australian | 106,524 | 74,128 or 79% | 46% | 75,623 or 71% |

| Dutch Australian | 78,924 | 62,495 or 79% | 52% | 59,502 or 75% |

| Croatian Australian | 50,996 | 35,598 or 70% | 43% | 48,271 or 95% |

Not all of those enumerated would have arrived as post-war migrants, specific statistics as at 2006 are not available.

Numbers

[edit]In September 2022, the Albanese government increased the permanent migration intake from 160,000 to a record 195,000 a year.[30][31][32] Net overseas migration is expected to reach 650,000 over 2022–2023, and 2023–2024, the highest in Australian history.[33]

| Period | Migration programme[34][35] |

|---|---|

| 1998–99 | 68 000 |

| 1999–00 | 70 000 |

| 2000–01 | 76 000 |

| 2001–02 | 85 000 |

| 2002–03 | 108,070 |

| 2003–2004 | 114,360 |

| 2004–2005 | 120,060 |

| 2005 | 142,933 |

| 2006 | 148,200 |

| 2007 | 158,630 |

| 2008 | 171,318 |

| 2011 | 185,000 |

| 2012 | 190,000 |

| 2013 | 190,000[36][37] |

| 2015-2016 | 190,000[38] |

| 2016-2017 | 190,000[39] |

| 2017-2018 | 190,000[40] |

| 2018-2019 | 190,000[41] |

| 2023-2024 | 190,000[42] |

See also

[edit]- Demographics of Australia

- European Australians

- Europeans in Oceania

- Immigration history of Australia

Notes

[edit]- ^ 1950 = Third highest figure per Department of Immigration timeline: In 1919 Net Overseas Migration was 166,303 when troops returned from World War I and in 1988 it was 172,794.

- ^ Immigration: Federation to Century's End 1901–2000: "Settler arrivals by birthplace data not available prior to 1959. For the period July 1949 to June 1959, Permanent and Long Term Arrivals by Country of Last Residence have been included as a proxy for this data. When interpreting this data for some countries...in the period immediately after World War II, there were large numbers of displaced persons whose country of last residence was not necessarily the same as their birthplace."[21]

- ^ Note this period covers 11 years rather than a decade.

- ^ Yugoslavia recorded until 1994–95 inclusive.

- ^ 3,602,573 Australian residents were aged 60 or over as a proportion of 19,855,288.[29][verification needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Price, CA (September 1998). "Post-war Immigration: 1947–98". Journal of the Australian Population Association. 15 (2): 115–129. Bibcode:1998JAuPA..15..115P. doi:10.1007/BF03029395. JSTOR 41110466. PMID 12346545. S2CID 28530319.

- ^ a b c d e "Immigration to Australia During the 20th Century – Historical Impacts on Immigration Intake, Population Size and Population Composition – A Timeline" (PDF). Department of Immigration and Citizenship (Australia). 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ "National Museum of Australia - Billy Hughes".

- ^ Jan Bassett (1986) pp. 138–39

- ^ Tündern-Smith, Ann (23 May 2008). "What is the Fifth Fleet?". Fifth Fleet Press. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ Franklin, James; Nolan, Gerry O (2023). Arthur Calwell. Connor Court. pp. 37–41. ISBN 9781922815811.

- ^ James Franklin (2009). "Calwell, Catholicism and the origins of multicultural Australia" (PDF). Proceedings. ACHS Conference 2009. pp. 42–54. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ "Look at Life – Immigration to Australia 1950s 1960s" on YouTube

- ^ "Ten Pound Poms". ABC Television (Australia). 1 November 2007.

- ^ "Ten Pound Poms". Immigration Museum. Museum Victoria. 10 May 2009. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010.

- ^ Michael Dugan and Josef Swarc (1984) p. 139

- ^ a b "The Snowy Mountains Scheme". Culture and Recreation Portal. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (Australia). 20 March 2008. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g "of Immigration and Citizenship (Australia)". 2007. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ a b c Neumann, Klaus (2003). "Providing a 'home for the oppressed'? Historical perspectives on Australian responses to refugees". Australian Journal of Human Rights. 9 (2): 1–25. doi:10.1080/1323238X.2003.11911103. ISSN 1323-238X. S2CID 150421238. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

King, Jackie (2003). "Australia and Canada Compared: The Reaction to the Kosovar Crisis". Australian Journal of Human Rights. 9 (2): 27–46. doi:10.1080/1323238X.2003.11911104. ISSN 1323-238X. S2CID 168919791. Retrieved 21 May 2019. - ^ a b c d e f g "Bonegilla Migrant Centre – Camp Block 19". Aussie Heritage. 2007. Archived from the original on 9 August 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ^ "Mr Arthur Calwell with the Kalnins family – the 50,000th New Australian – CU914/1" (Photograph). National Archives of Australia. 1949. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "Migrant Arrivals in Australia – 50,000th Dutch migrant, arrives in Australia aboard the SIBAJAK. Miss Scholte presents Australia's Minister for Immigration, Mr. H. E. Holt, with inscribed Delft plates, which she brought as goodwill gifts from Netherlands Government" (Photograph). National Archives of Australia. 1954. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "1940s–60s – A Journey for Many". Journeys to Australia. Museums Victoria. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "Marketing Migrants". Horizons (exhibition): The peopling of Australia since 1788. National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 29 July 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

- ^ "Their Country's Good". Time. 21 November 1955. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

Only in the decade since World War II has Australia, by means of a vast and wisely planned immigration scheme, banished the last vestiges of the emigration stigma. Last week the drums were beating as, with much eclat, bright and chirpy Barbara Porritt stepped ashore at Melbourne. She was Australia's millionth immigrant since 1945.

- ^ a b Immigration: Federation to Century's End 1901–2000 (PDF) (Report). Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs. October 2001. p. 25. ISSN 1446-0033. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Migrant accommodation". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Migrant Hostels in Australia". Sharpes On Line. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Migrant hostels in New South Wales, 1946–78 – Fact sheet 170". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Post Office List". Premier Postal Auctions. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ "Bathurst Migrant Camp". A Place For Everyone – Bathurst Migrant Camp 1948 – 1952. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ "Point Walter Former Army Camp Site (whole site including watch house)". in Herit. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d "2914.0.55.002 2006 Census Ethnic Media Package" (Excel). Census Dictionary, 2006 (cat.no: 2901.0). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 27 June 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- ^ "Cat. No. 2068.0 – 2006 Census Tables: Age (Full Classification List) by sex – Count of persons (excludes overseas visitors)". 2006 Census of Population and Housing Australia (Australia). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 27 June 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2008.[dead link]

"Improved access to historical Census data". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 21 May 2019. - ^ Clun, David Crowe, Angus Thompson, Rachel (2 September 2022). "Albanese government will increase permanent migration to record 195,000". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Australia's migration future". minister.homeaffairs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Australia raises permanent migration cap to 195,000 to ease workforce shortages". the Guardian. 2 September 2022. Archived from the original on 2 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ "What's behind the recent surge in Australia's net migration – and will it last?". 5 April 2023. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ "Fact sheet - Key facts about immigration". Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ corporateName=Commonwealth Parliament; address=Parliament House, Canberra. "Australia's Migration Program". www.aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-migration-programme-2013-14.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-statistics/statistics/visa-statistics/live/migration-program [bare URL]

- ^ https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/2015-16-migration-programme-report.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-on-migration-program-2016-17.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-migration-program-2017-18.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-migration-program-2018-19.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/what-we-do/migration-program-planning-levels#:~:text=In%20the%202024%E2%80%9325%20Migration,21%20and%202021%E2%80%9322%20respectively. [bare URL]

Further reading

[edit]- Markus, Andrew (1984). "Labour and Immigration 1946-9: The Displaced Persons Program". Labour History (47). Australian Society for the Study of Labour History: 73–90. doi:10.2307/27508686. ISSN 0023-6942. JSTOR 27508686.

External links

[edit]- "Migration". National Museum of Australia.

- "History of migration to Australia". NSW Migration Heritage Centre. (archived website)

- "Home page". Migration Museum. (South Australia)

- "Immigration Museum". Museums Victoria.

- "Immigration Stories". Western Australian Museum.

- "Home page". Museum of Chinese Australian History.

- "World War II Refugees to Australia". Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild. Ships and passenger lists