Pole of Inaccessibility research station

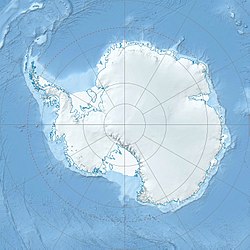

Pole of Inaccessibility

Полюс недоступности | |

|---|---|

The station buried under snow showing the bust of Lenin in January 2007 | |

| Coordinates: 82°06′42″S 55°01′57″E / 82.1117°S 55.0325°E[1] | |

| Region | Kemp Land |

| Established | 14 December 1958 |

| Closed | 26 December 1958 |

| Named for | Southern pole of inaccessibility |

| Government | |

| • Type | Administration |

| • Body | SAE, Soviet Union |

| Elevation | 3,800 m (12,500 ft) |

| Active times | One summer |

The Pole of Inaccessibility research station (Russian: Полюс недоступности, Polyus nedostupnosti) is a defunct Soviet research station in Kemp Land, Antarctica, at the southern pole of inaccessibility (the point in Antarctica furthest from any ocean) as defined in 1958 when the station was established. Later definitions give other locations, all relatively near this point. It performed meteorological observations from 14 to 26 December 1958. The Pole of Inaccessibility has the world's coldest year-round average temperature of −58.2 °C (−72.8 °F).[2]

It is 878 km (546 mi) from the South Pole, and approximately 600 km (370 mi) from Sovetskaya. The surface elevation is 3,724 meters (12,218 feet). It was reached on 14 December 1958 by an 18-man traversing party of the 3rd Soviet Antarctic Expedition.[3] Its WMO ID is 89550.[4]

History

[edit]Equipment and personnel were delivered by an Antarctic tractor convoy operated by the 3rd Soviet Antarctic Expedition. The station had a hut for four people, a radio shack, and an electrical hut. These buildings had been constructed on the tractors used during the traverse, serving as accommodation. Next to the hut, an airstrip was cleared and a Li-2 aircraft landed there on 18 December 1958. The outpost was equipped with a diesel power generator and a transmitter. On 26 December the outpost was vacated indefinitely. Four researchers were airlifted out, and the remaining 14 members of the party returned with the tractors. The station was deemed to be too far from other research stations to allow safe permanent operation, so it was left to be used for future short-term visits only.[5]

The 8th Soviet Antarctic Expedition visited the site on 1 February 1964 and left five days later.[6]

The American Queen Maud Land Traverse reached the Pole of Inaccessibility from Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station on 27 January 1965. The crew were flown out by a C-130 on 1 February. On 15 December 1965 a new American crew arrived by C-130 to make observations, refurbish the snowcats, and continue the Queen Maud Land Traverse, zig-zagging to the newly installed Plateau Station, where they arrived on 29 January 1966.[7]

The 12th Soviet Antarctic Expedition visited the site in 1967.[6]

On 19 January 2007, the British Team N2i reached the Pole of Inaccessibility using specially-designed foil kites.[8]

On 27 December 2011, during the Antarctica Legacy Crossing, Sebastian Copeland, and partner Eric McNair-Landry, reached the Pole of Inaccessibility by foot and kite ski from the Novolazarevskaya station, on their way to completing the first partial east–west transcontinental crossing of Antarctica of over 4,100 km (2,500 mi).

Historic site

[edit]The station building is surmounted by a bust of Vladimir Lenin facing Moscow. As of 2007, it is almost entirely buried by snow, with little more than the bust visible.[8] Following a proposal by Russia to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting, the buried building and emergent bust, along with a plaque commemorating the conquest of the Pole of Inaccessibility by Soviet Antarctic explorers in 1958, has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 4).[1]

See also

[edit]- Soviet Antarctic Expedition

- List of Antarctic research stations

- List of Antarctic field camps

- Henry Cookson, British Adventurer

- Historic Sites and Monuments in Antarctica

References

[edit]- ^ a b "List of Historic Sites and Monuments approved by the ATCM (2012)" (PDF). Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ Crowder, Bob; Robertson, Ted; Vallier-Talbot, Eleanor; Whitaker, Richard. Weather (Revised and updated ed.). William J. Burroughs. p. 59.

- ^ Nudel'man, A. V. (1959). Soviet Antarctic Expeditions 1955-1959. Moscow: Izdatel'stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR.

- ^ "Catalogue of Russian Federation Antarctic Meteorology Data". Laboratory of Ocean and Climate Antarctic Studies, Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ А.С. ЛАЗАРЕВ (December 16, 2008). ДОСТИЖЕНИЕ ПОЛЮСА НЕДОСТУПНОСТИ (in Russian). Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ^ a b "Norwegian-U.S. Scientific Traverse of East Antarctica". Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ Cameron, R. L.; Picciotto, E.; Kane, H.S.; Gliozzi, J. (April 1968). Glaciology of the Queen Maud Land Traverse, 1964-65 South Pole – Pole of Relative Inaccessibility (Technical report). Research Foundation and the Institute of Polar Studies. hdl:1811/38761.

- ^ a b "Team N2i successfully conquer the Pole of Inaccessibility by foot and kite on 19th Jan '07". Archived from the original on August 16, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

Further reading

[edit]![]() Media related to Pole of inaccessibility at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pole of inaccessibility at Wikimedia Commons

- Outposts of Antarctica

- Outposts of Kemp Land

- Russia and the Antarctic

- Soviet Union and the Antarctic

- Monuments and memorials to Vladimir Lenin

- Historic buildings and structures in Antarctica

- Former populated places in Antarctica

- 1958 establishments in Antarctica

- 1958 disestablishments in Antarctica

- 1958 establishments in the Soviet Union