Political career of John C. Breckinridge

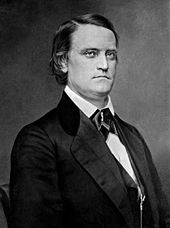

The political career of John C. Breckinridge included service in the state government of Kentucky, the Federal government of the United States, as well as the government of the Confederate States of America. In 1857, 36 years old, he was inaugurated as Vice President of the United States under James Buchanan. He remains the youngest person to ever hold the office. Four years later, he ran as the presidential candidate of a dissident group of Southern Democrats, but lost the election to the Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln.

A member of the Breckinridge political family, John C. Breckinridge became the first Democrat to represent Fayette County in the Kentucky House of Representatives, and in 1851, he was the first Democrat to represent Kentucky's 8th congressional district in over 20 years. A champion of strict constructionism, states' rights, and popular sovereignty, he supported Stephen A. Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act as a means of addressing slavery in the territories acquired by the U.S. in the Mexican–American War. Considering his re-election to the House of Representatives unlikely in 1854, he returned to private life and his legal practice. He was nominated for vice president at the 1856 Democratic National Convention, and although he and Buchanan won the election, he enjoyed little influence in Buchanan's administration.

In 1859, the Kentucky General Assembly elected Breckinridge to a U.S. Senate term that would begin in 1861. In the 1860 United States presidential election, Breckinridge captured the electoral votes of most of the Southern states, but finished a distant second among four candidates. Lincoln's election as president prompted the secession of the Southern states to form the Confederate States of America. Though Breckinridge sympathized with the Southern cause, in the Senate he worked futilely to reunite the states peacefully. After the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, beginning the Civil War, he opposed allocating resources for Lincoln to fight the Confederacy. Fearing arrest after Kentucky sided with the Union, he fled to the Confederacy, joined the Confederate States Army, and was subsequently expelled from the Senate. He served in the Confederate Army from October 1861 to February 1865, when Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed him Confederate States Secretary of War. Then, concluding that the Confederate cause was hopeless, he encouraged Davis to negotiate a national surrender. Davis's capture on May 10, 1865, effectively ended the war, and Breckinridge fled to Cuba, then Great Britain, and finally Canada, remaining in exile until President Andrew Johnson's offer of amnesty in 1868. Returning to Kentucky, he refused all requests to resume his political career and died of complications related to war injuries in 1875.

Formative years

[edit]

Historian James C. Klotter has speculated that, had John C. Breckinridge's father, Cabell, lived, he would have steered his son to the Whig Party and the Union, rather than the Democratic Party and the Confederacy, but the Kentucky Secretary of State and former Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives died of a fever on September 1, 1823, months before his son's third birthday.[1] Burdened with her husband's debts, widow Mary Breckinridge and her children moved to her in-laws' home near Lexington, Kentucky, where John C. Breckinridge's grandmother taught him the political philosophies of his late grandfather, U.S. Attorney General John Breckinridge.[2] John Breckinridge believed the federal government was created by, and subject to, the co-equal governments of the states.[3] As a state representative, he introduced the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 and 1799, which denounced the Alien and Sedition Acts and asserted that states could nullify them and other federal laws that they deemed unconstitutional.[4] A strict constructionist, he held that the federal government could only exercise powers explicitly given to it in the Constitution.[4]

Most of the Breckinridges were Whigs, but John Breckinridge's posthumous influence inclined his grandson toward the Democratic Party.[5][6] Additionally, John C. Breckinridge's friend and law partner, Thomas W. Bullock, was from a Democratic family.[7] In 1842, Bullock told Breckinridge that by the time they opened their practice in Burlington, Iowa, "you were two-thirds of a Democrat"; living in heavily Democratic Iowa Territory further distanced him from Whiggery.[8] He wrote weekly editorials in the Democratic Iowa Territorial Gazette and Advisor, and in February 1843, he was named to the Des Moines County Democratic committee.[9] A letter from Breckinridge's brother-in-law related that, when Breckinridge's uncle William learned that his nephew had "become loco-foco",[note 1] he said, "I felt as I would have done if I had heard that my daughter had been dishonored."[9] On a visit to Kentucky in 1843, Breckinridge met and married Mary Cyrene Burch, ending his time in Iowa.[10]

Views on slavery

[edit]Slavery issues dominated Breckinridge's political career, although historians disagree about Breckinridge's views. In Breckinridge: Statesman, Soldier, Symbol, William C. Davis argues that, by adulthood, Breckinridge regarded slavery as evil; his entry in the 2002 Encyclopedia of World Biography records that he advocated voluntary emancipation.[5][11] In Proud Kentuckian: John C. Breckinridge 1821–1875, Frank Heck disagrees, citing Breckinridge's consistent advocacy for slavery protections, beginning with his opposition to emancipationist candidates—including his uncle, Robert Jefferson Breckinridge—in the state elections of 1849.[12]

Early influences

[edit]Breckinridge's grandfather, John, owned slaves, believing it was a necessary evil in an agrarian economy.[13] He hoped for gradual emancipation but did not believe the federal government was empowered to effect it; Davis wrote that this became "family doctrine".[13] As a U.S. Senator, John Breckinridge insisted that decisions about slavery in Louisiana Territory be left to its future inhabitants, essentially the "popular sovereignty" advocated by John C. Breckinridge prior to the Civil War.[14] John C. Breckinridge's father, Cabell, embraced gradual emancipation and opposed government interference with slavery, but Cabell's brother Robert, a Presbyterian minister, became an abolitionist, concluding that slavery was morally wrong.[15][16] Davis recorded that all the Breckinridges were pleased when the General Assembly upheld the ban on importing slaves to Kentucky in 1833.[17]

John C. Breckinridge encountered conflicting influences as an undergraduate at Centre College and in law school at Transylvania University.[18] Centre President John C. Young, Breckinridge's brother-in-law, believed in states' rights and gradual emancipation, as did George Robertson, one of Breckinridge's instructors at Transylvania, but James G. Birney, father of Breckinridge's friend and Centre classmate William Birney, was an abolitionist.[18] In an 1841 letter to Robert Breckinridge, who became his surrogate father after Cabell Breckinridge's death, John C. Breckinridge wrote that only "ignorant, foolish men" feared abolition.[19][20] In an Independence Day address in Frankfort later that year, he decried the "unlawful dominion over the bodies ... of men".[11] An acquaintance believed that Breckinridge's move to Iowa Territory was motivated, in part, by the fact that it was a free territory under the Missouri Compromise.[21]

After returning to Kentucky, Breckinridge became friends with abolitionists Cassius Marcellus Clay, Garrett Davis, and Orville H. Browning.[22] He represented freedmen in court and loaned them money.[19] He was a Freemason and member of the First Presbyterian Church, both of which opposed slavery.[22] Nevertheless, because blacks were educationally and socially disadvantaged in the South, Breckinridge concluded that "the interests of both races in the Commonwealth would be promoted by the continuance of their present relations".[23] He supported the new state constitution adopted in 1850, which forbade the immigration of freedmen to Kentucky and required emancipated slaves to be expelled from the state.[24] Believing it was best to relocate freedmen to the African colony of Liberia, he supported the Kentucky branch of the American Colonization Society.[19][20] The 1850 Census showed that Breckinridge owned five slaves, aged 11 to 36.[25] Heck recorded that his slaves were well-treated but noted that this was not unusual and proved nothing about his views on slavery.[12]

Moderate reputation

[edit]Because Breckinridge defended both the Union and slavery in the General Assembly, he was considered a moderate early in his political career.[26] In June 1864, Pennsylvania's John W. Forney opined that Breckinridge had been "in no sense an extremist" when elected to Congress in 1851.[26] Of his early encounters with Breckinridge, Forney wrote: "If he had a conscientious feeling, it was hatred of slavery, and both of us, 'Democrats' as we were, frequently confessed that it was a sinful and an anti-Democratic institution, and that the day would come when it must be peaceably or forcibly removed."[12][27] Heck discounts this statement, pointing out that Forney was editor of a pro-Union newspaper and Breckinridge a Confederate general at the time it was published.[28] As late as the 1856 presidential election, some alleged that Breckinridge was an abolitionist.[19]

By the time he began his political career, Breckinridge had concluded that slavery was more a constitutional issue than a moral one.[16] Slaves were property, and the Constitution did not empower the federal government to interfere with property rights.[29] From Breckinridge's constructionist viewpoint, allowing Congress to legislate emancipation without constitutional sanction would lead to "unlimited dominion over the territories, excluding the people of the slave states from emigrating thither with their property".[30] As a private citizen, he supported the slavery protections in the Kentucky Constitution of 1850 and denounced the Wilmot Proviso, which would have forbidden slavery in territory acquired in the Mexican–American War.[19] As a state legislator, he declared slavery a "wholly local and domestic" matter, to be decided separately by the residents of each state and territory.[31] Because Washington, D.C., was a federal entity and the federal government could not interfere with property rights, he concluded that forced emancipation there was unconstitutional.[31] As a congressman, he insisted on Congress's "perfect non-intervention" with slavery in the territories.[32] Debating the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act, he explained, "The right to establish [slavery in a territory by government sanction] involves the correlative right to prohibit; and, denying both, I would vote for neither."[33]

Later views

[edit]Davis notes that Breckinridge's December 21, 1859, address to the state legislature marked a change in his public statements about slavery.[34] He decried the Republicans' desire for "negro equality", his first public indication that he may have believed blacks were biologically inferior to whites.[34] He declared that the Dred Scott decision showed that federal courts afforded adequate protection for slave property, but advocated a federal slave code if future courts failed to enforce those protections; this marked a departure from his previous doctrine of "perfect non-interference".[34][35] Asserting that John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry proved Republicans intended to force abolition on the South, he predicted "resistance [to the Republican agenda] in some form is inevitable".[19] He still urged the Assembly against secession—"God forbid that the step shall ever be taken!"—but his discussion of growing sectional conflict bothered some, including his uncle Robert.[36]

Klotter wrote that Breckinridge's sale of a female slave and her six-week-old child in November 1857 probably ended his days as a slaveholder.[19] Slaves were not listed among his assets in the 1860 Census, but Heck noted that he had little need for slaves at that time, since he was living in Lexington's Phoenix Hotel after returning to Kentucky from his term as vice president.[37] Some slavery advocates refused to support him in the 1860 presidential race because he was not a slaveholder.[38] Klotter noted that Breckinridge fared better in rural areas of the South, where there were fewer slaveholders; in urban areas where the slave population was higher, he lost to Constitutional Unionist candidate John Bell, who owned 166 slaves.[39] William C. Davis recorded that, in most of the South, the combined votes for Bell and Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas exceeded those cast for Breckinridge.[40]

After losing the election to Abraham Lincoln, Breckinridge worked for adoption of the Crittenden Compromise—authored by fellow Kentuckian John J. Crittenden—as a means of preserving the Union.[41] Breckinridge believed the Crittenden proposal—restoring the Missouri Compromise line as the separator between slave and free territory in exchange for stricter enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and federal non-interference with slavery in the territories and Washington, D.C.—was the most extreme proposal to which the South would agree.[42][43] Ultimately, the compromise was rejected and the Civil War soon followed.[44]

Early political career

[edit]A supporter of the annexation of Texas and "manifest destiny", Breckinridge campaigned for James K. Polk in the 1844 presidential election, prompting a relative to observe that he was "making himself very conspicuous here by making flaming loco foco speeches at the Barbecues".[45][46] He decided against running for Scott County clerk after his law partner complained that he spent too much time in politics.[47] In 1845, he declined to seek election to the U.S. House of Representatives from the eighth district but campaigned for Alexander Keith Marshall, his party's unsuccessful nominee.[47][48] He supported Zachary Taylor for the presidency in mid-1847 but endorsed the Democratic ticket of Lewis Cass and William O. Butler after Taylor became a Whig in 1848.[48]

Kentucky House of Representatives

[edit]

In October 1849, Kentucky voters called for a constitutional convention.[49] Emancipationists, including Breckinridge's uncles William and Robert, his brother-in-law John C. Young, and his friend Cassius Marcellus Clay, nominated "friends of emancipation" to seek election to the convention and the state legislature[49] In response, Breckinridge, who opposed "impairing [slavery protections] in any form",[50] was nominated by a bipartisan pro-slavery convention for one of Fayette County's two seats in the Kentucky House of Representatives.[6][50] With 1,481 votes, 400 more than any of his opponents, Breckinridge became the first Democrat elected to the state legislature from Fayette County, which was heavily Whig.[31][51]

When the House convened in December 1849, a member from Mercer County nominated Breckinridge for Speaker against two Whigs.[52] After receiving 39 votes—8 short of a majority—on the first three ballots, he withdrew, and the position went to Whig Thomas Reilly.[31][52] Assigned to the committees on the Judiciary and Federal Relations, Breckinridge functioned as the Democratic floor leader during the session.[31][53] Davis wrote that his most important work during the session was bank reform.[52]

Breckinridge's first speech favored allowing the Kentucky Colonization Society to use the House chamber; later, he advocated directing Congress to establish an African freedmen colony, and to meet the costs of transporting settlers there.[24] Funding internal improvements was traditionally a Whig stance, but Breckinridge advocated conducting a state geologic survey, making the Kentucky River more navigable, chartering a turnpike, incorporating a steamboat company, and funding the Kentucky Lunatic Asylum.[52] As a reward for supporting these projects, he presided over the approval of the Louisville and Bowling Green Railroad's charter and was appointed director of the asylum.[54]

Resolutions outlining Kentucky's views on the proposed Compromise of 1850 were referred to the Committee on Federal Relations.[55] The committee's Whig majority favored one calling the compromise a "fair, equitable, and just basis" for dealing with slavery in the territories and urging Congress not to interfere with slavery there or in Washington, D.C.[55] Feeling this left open the issue of Congress's ability to legislate emancipation, Breckinridge asserted in a competing resolution that Congress could not establish or abolish slavery in states or territories.[31][55] Both resolutions, and several passed by the state Senate, were laid on the table without being adopted.[55]

Breckinridge left the session on March 4, 1850, three days before its adjournment, to tend to John Milton Breckinridge, his infant son who had fallen ill; the boy died on March 18.[56] To distract from his grief, he campaigned for ratification of the new constitution, objecting only to its difficult amendment process.[57] He declined renomination, citing concerns "of a private and imperative nature".[58] Davis wrote that the problem was money, since his absence from Lexington had hurt his legal practice, but his son's death was also a factor.[58]

U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]At an October 17, 1850, barbecue celebrating the Compromise of 1850, Breckinridge toasted its author, Whig Party founder Henry Clay.[59] Clay reciprocated by praising Breckinridge's grandfather and father, expressing hope that Breckinridge would use his talents to serve his country, then embracing him.[60][61] Some observers believed that Clay was endorsing Breckinridge for higher office, and Whig newspapers began referring to him as "a sort of half-way Whig" and implying that he voted for Taylor in 1848.[61]

First term (1851–1853)

[edit]Delegates to the Democrats' January 1851 state convention nominated Breckinridge to represent Kentucky's eighth district in the U.S. House of Representatives.[30][62] Called the "Ashland district" because it contained Clay's Ashland estate and much of the area he once represented, Whigs typically won there by 600 to 1,000 votes.[30] A Democrat had not represented it since 1828, and in the previous election no Democrat had sought the office.[30][63] Breckinridge's opponent, Leslie Combs, was a popular War of 1812 veteran and former state legislator.[64] As they campaigned together, Breckinridge's eloquence contrasted with Combs' plainspoken style.[65][66] Holding that "free thought needed free trade", Breckinridge opposed Whig protective tariffs.[31] He only favored federal funding of internal improvements "of a national character".[31] Carrying only three of seven counties, but bolstered by a two-to-one margin in Owen County, Breckinridge garnered 54% of the vote, winning the election by a margin of 537.[64][67]

Considered for Speaker of the House, Breckinridge believed his election unlikely and refused to run against fellow Kentuckian Linn Boyd.[68] Boyd was elected, and despite Breckinridge's gesture, assigned him to the lightly regarded Foreign Affairs Committee.[69] Breckinridge resisted United States Democratic Review editor George Nicholas Sanders' efforts to recruit him to the Young America movement.[70] Like Young Americans, Breckinridge favored westward expansion and free trade, but he disagreed with the movement's support of European revolutions and its disdain for older statesmen.[70] On March 4, 1852, Breckinridge made his first speech in the House, defending presidential aspirant William Butler against charges by Florida's Edward Carrington Cabell, a Young American and distant cousin, that Butler secretly sympathized with the Free Soilers.[71] He denounced Sanders for his vitriolic attacks on Butler and for calling all likely Democratic presidential candidates except Stephen Douglas "old fogies".[72]

The speech made Breckinridge a target of Whigs, Young Americans, and Douglas supporters.[73] Humphrey Marshall, a Kentucky Whig who supported incumbent President Millard Fillmore, attacked Breckinridge for claiming Fillmore had not fully disclosed his views on slavery.[74] Illinois' William Alexander Richardson, a Douglas backer, tried to distance Douglas from Sanders' attacks on Butler, but Breckinridge showed that Douglas endorsed the Democratic Review a month after it printed its first anti-Butler article.[75] Finally, Breckinridge's cousin, California's Edward C. Marshall, charged that Butler would name Breckinridge Attorney General in exchange for his support and revived the charge that Breckinridge broke party ranks, supporting Zachary Taylor for president.[76] Breckinridge ably defended himself, but Sanders continued to attack him and Butler, claiming Butler would name Breckinridge as his running mate, even though Breckinridge was too young to qualify as vice president.[77]

After his maiden speech, Breckinridge took a more active role in the House.[77] In debate with Ohio's Joshua Reed Giddings, he defended the Fugitive Slave Law's constitutionality and criticized Giddings for hindering the return of fugitive slaves.[77][78] He opposed Tennessee Congressman Andrew Johnson's Homestead Bill, fearing it would create more territories that excluded slavery.[77] Although generally opposed to funding local improvements, he supported the repair of two Potomac River bridges to avoid higher costs later.[78] Other minor stands included supporting measures to benefit his district's hemp farmers, voting against giving the president ten more appointments to the U.S. Naval Academy, and opposing funds for a sculpture of George Washington because the sculptor proposed depicting Washington in a toga.[69][78]

Beginning in April, Breckinridge made daily visits to an ailing Henry Clay.[79] Clay died June 29, 1852, and Breckinridge garnered nationwide praise and enhanced popularity in Kentucky after eulogizing Clay in the House.[69][80] Days later, he spoke in opposition to increasing a subsidy to the Collins Line for carrying trans-Atlantic mail, noting that Collins profited by carrying passengers and cargo on mail ships.[81] In wartime, the government could commandeer and retrofit Collins's steamboats as warships, but Breckinridge cited Commodore Matthew C. Perry's opinion that they would be useless in war.[81] Finally, he showed Cornelius Vanderbilt's written statement promising to build a fleet of mail ships at his expense and carry the mail for $4 million less than Collins.[81] Despite this, the House approved the subsidy increase.[82]

Second term (1853–1855)

[edit]With Butler's chances for the presidential nomination waning, Breckinridge convinced the Kentucky delegation to the 1852 Democratic National Convention not to nominate Butler until later balloting when he might become a compromise candidate.[82] He urged restraint when Lewis Cass's support dropped sharply on the twentieth ballot, but Kentucky's delegates would wait no longer; on the next ballot, they nominated Butler, but he failed to gain support.[82] After Franklin Pierce, Breckinridge's second choice, was nominated, Breckinridge tried, unsuccessfully, to recruit Douglas to Pierce's cause.[83] Pierce lost by 3,200 votes in Kentucky—one of four states won by Winfield Scott—but was elected to the presidency, and appointed Breckinridge governor of Washington Territory in recognition of his efforts.[83][84] Unsure of his re-election chances in Kentucky, Breckinridge had sought the appointment, but after John J. Crittenden, rumored to be his challenger, was elected to the Senate in 1853, he decided to decline it and run for re-election.[85]

Election

[edit]

The Whigs chose Attorney General James Harlan to oppose Breckinridge, but he withdrew in March when some party factions opposed him.[86] Robert P. Letcher, a former governor who had not lost in 14 elections, was the Whigs' second choice.[87] Letcher was an able campaigner who combined oratory and anecdotes to entertain and energize an audience.[65] Breckinridge focused on issues in their first debate, comparing the Whig Tariff of 1842 to the Democrats' lower Walker tariff, which increased trade and yielded more tax revenue.[88] Instead of answering Breckinridge's points, Letcher appealed to party loyalty, claiming Breckinridge would misrepresent the district "because he is a Democrat".[89] Letcher appealed to Whigs "to protect the grave of Mr. [Henry] Clay from the impious tread of Democracy",[note 2] but Breckinridge pointed to his friendly relations with Clay, remarking that Clay's will did not mandate that "his ashes be exhumed" and "thrown into the scale to influence the result of the present Congressional contest".[89]

Cassius Clay, Letcher's political enemy, backed Breckinridge despite their differences on slavery.[66] Citing Clay's support and the abolitionism of Breckinridge's uncle Robert, Letcher charged that Breckinridge was an abolitionist.[90] In answer, Breckinridge quoted newspaper accounts and sworn testimony, provided by John L. Robinson, of a speech Letcher made in Indiana for Zachary Taylor in 1848.[91] In the speech, made alongside Thomas Metcalfe, another former Whig governor of Kentucky, Letcher predicted that the Kentucky Constitution then being drafted would provide for gradual emancipation, declaring, "It is only the ultra men in the extreme South who desire the extension of slavery."[91]

When Letcher confessed doubts about his election chances, Whigs began fundraising outside the district, using the money to buy votes or pay Breckinridge supporters not to vote.[92] Breckinridge estimated that the donations, which came from as far away as New York and included contributions from the Collins Line, totaled $30,000; Whig George Robertson believed it closer to $100,000.[66][93] Washington, D.C., banker William Wilson Corcoran contributed $1,000 to Breckinridge, who raised a few thousand dollars.[92] Out of 12,538 votes cast, Breckinridge won by 526.[94] He received 71% of the vote in Owen County, which recorded 123 more votes than registered voters.[94] Grateful for the county's support, he nicknamed his son, John Witherspoon Breckinridge, "Owen".[90]

Service

[edit]Of 234 representatives in the House, Breckinridge was one of 80 re-elected to the Thirty-third Congress.[95] His relative seniority, and Pierce's election, increased his influence.[95] He was rumored to have Pierce's backing for Speaker of the House, but he again deferred to Boyd; Maryland's Augustus R. Sollers spoiled Boyd's unanimous election by voting for Breckinridge.[96] Still not given a committee chairmanship, he was assigned to the Ways and Means Committee, where he secured passage of a bill to cover overspending in fiscal year 1853–1854; it was the only time in his career that he solely managed a bill.[97] His attempts to increase Kentucky's allocation in a rivers and harbors bill were unsuccessful but popular with his Whig constituents.[69]

In January 1854, Douglas introduced the Kansas–Nebraska Act to organize the Nebraska Territory.[98] Southerners had thwarted his previous attempts to organize the territory because Nebraska lay north of parallel 36°30' north, the line separating slave and free territory under the Missouri Compromise.[99] They feared that the territory would be organized into new free states that would vote against the South on slavery issues.[99] The Kansas–Nebraska Act allowed the territory's settlers to decide whether or not to permit slavery, an implicit repeal of the Missouri Compromise.[99] Kentucky Senator Archibald Dixon's amendment to make the repeal explicit angered northern Democrats, but Breckinridge believed it would move the slavery issue from national to local politics, and he urged Pierce to support it.[100][101] Breckinridge wrote to his uncle Robert that he "had more to do than any man here, in putting [the Act] in its present shape",[78] but Heck notes that few extant records support this claim.[78] The repeal amendment made the act more palatable to the South; only 9 of 58 Southern congressmen voted against it.[102] No Northern Whigs voted for the measure, but 44 of 86 Northern Democrats voted in the affirmative, enough to pass it.[102] The Senate quickly concurred, and Pierce signed the act into law on May 30, 1854.[102]

During the debate on the bill, New York's Francis B. Cutting demanded that Breckinridge retract or explain a statement he had made, which Breckinridge understood as a challenge to duel.[64] Under the code duello, the challenged party selected the weapons and the distance between combatants; Breckinridge chose rifles at 60 paces and suggested the duel be held in Silver Spring, Maryland, on the estate of his friend, Francis Preston Blair.[64][103] Cutting had not meant his remark as a challenge, but insisted that he was now challenged and selected pistols at 10 paces.[64] While their representatives tried to clarify matters, Breckinridge and Cutting made amends, averting the duel.[64] Had it taken place, Breckinridge could have been removed from the House; the 1850 Kentucky Constitution prevented duelers from holding office.[103]

In the second session of the 33rd Congress, Breckinridge acted as spokesman for Ways and Means Committee bills, including a bill to assume and pay the debts Texas incurred prior to its annexation.[104] Breckinridge's friends, W. W. Corcoran and Jesse D. Bright, were two of Texas's major creditors.[104] The bill, which was approved, paid only those debts related to powers Texas surrendered to Congress upon annexation.[105] Breckinridge was disappointed that the House defeated a measure to pay the Sioux $12,000 owed them for the 1839 purchase of an island in the Mississippi River; the debt was never paid.[105] Another increase in the subsidy to the Collins Line passed over his opposition, but Pierce vetoed it.[105]

Retirement from the House

[edit]In February 1854, the General Assembly's Whig majority gerrymandered the eighth district, removing over 500 Democratic voters and replacing them with several hundred Whig voters by removing Owen and Jessamine counties from the district and adding Harrison and Nicholas counties to it.[106] The cooperation of the Know Nothing Party—a relatively new nativist political entity—with the faltering Whigs further hindered Breckinridge's re-election chances.[106] With his family again in financial straits, his wife wanted him to retire from national politics.[106]

Pierre Soulé, the U.S. Minister to Spain, resigned in December 1854 after being unable to negotiate the annexation of Cuba and angering the Spanish by drafting the Ostend Manifesto, which called for the U.S. to take Cuba by force.[107] Pierce nominated Breckinridge to fill the vacancy, but did not tell him until just before the Senate's January 16 confirmation vote.[108] After consulting Secretary of State William L. Marcy, Breckinridge concluded that the salary was insufficient and Soulé had so damaged Spanish relations that he would be unable to accomplish anything significant.[109] In a letter to Pierce on February 8, 1855, he cited reasons "of a private and domestic nature" for declining the nomination.[110] On March 17, 1855, he announced he would retire from the House.[110]

Breckinridge and Minnesota Territory's Henry Mower Rice were among the speculators who invested in land near present-day Superior, Wisconsin.[111] Rice disliked Minnesota's territorial governor, Willis A. Gorman, and petitioned Pierce to replace him with Breckinridge.[112] Pierce twice investigated Gorman, but found no grounds to remove him from office.[113] Breckinridge fell ill when traveling to view his investments in mid-1855 and was unable to campaign in the state elections.[114] Know Nothings captured every state office and six congressional districts—including the eighth district—and Breckinridge sent regrets to friends in Washington, D.C., promising to take a more active role in the 1856 campaigns.[115]

U.S. vice president

[edit]Two Kentuckians—Breckinridge's friend, Governor Lazarus W. Powell and his enemy, Linn Boyd—were potential Democratic presidential nominees in 1856.[116] Breckinridge—a delegate to the national convention and designated as a presidential elector—favored Pierce's re-election but convinced the state Democratic convention to leave the delegates free to support any candidate the party coalesced behind.[117] To a New Yorker who proposed that Breckinridge's nomination could unite the party, he replied "Humbug".[118]

Election

[edit]

Pierce was unable to secure the nomination at the national convention, so Breckinridge switched his support to Stephen Douglas, but the combination of Pierce and Douglas supporters did not prevent James Buchanan's nomination.[119] After Douglas's floor manager, William Richardson, suggested that nominating Breckinridge for vice president would help Buchanan secure the support of erstwhile Douglas backers in the general election, Louisiana's J. L. Lewis nominated him.[120] Breckinridge declined in deference to Linn Boyd but received 51 votes on the first ballot, behind Mississippi's John A. Quitman with 59, but ahead of third-place Boyd, who garnered 33.[121] On the second ballot, Breckinridge received overwhelming support, and opposition delegates changed their votes to make his nomination unanimous.[122]

The election was between Buchanan and Republican John C. Frémont in the north and between Buchanan and Millard Fillmore, nominated by a pro-slavery faction of the Know Nothings, in the South.[123] Tennessee Governor Andrew Johnson and Congressional Globe editor John C. Rives promoted the possibility that Douglas and Pierce supporters would back Fillmore in the Southern states, denying Buchanan a majority in the Electoral College and throwing the election to the House of Representatives.[124] There, Buchanan's opponents would prevent a vote, and the Senate's choice for vice president—certain to be Breckinridge—would become president.[124] There is no evidence that Breckinridge countenanced this scheme.[125] Defying contemporary political convention, Breckinridge spoke frequently during the campaign, stressing Democratic fidelity to the constitution and charging that the Republican emancipationist agenda would tear the country apart.[126] His appearances in the critical state of Pennsylvania helped allay Buchanan's fears that Breckinridge desired to throw the election to the House.[125] "Buck and Breck" won the election with 174 electoral votes to Frémont's 114 and Fillmore's 8, and Democrats carried Kentucky for the first time since 1828.[33][127] Thirty-six at the time of his inauguration on March 4, 1857, Breckinridge remains the youngest vice president in U.S. history.[128] The Constitution requires the president and vice-president to be at least thirty-five years old.

Service

[edit]When Breckinridge asked to meet with Buchanan shortly after the inauguration, Buchanan told him to come to the White House and ask to see the hostess, Harriet Lane.[129][note 3] Offended, Breckinridge refused to do so; Buchanan's friends later explained that asking to see Lane was a secret instruction to take a guest to the president.[129] Buchanan apologized for the misunderstanding, but the event portended a poor relationship between the two men.[130][131] Resentful of Breckinridge's support for both Pierce and Douglas, Buchanan allowed him little influence in the administration.[128] Breckinridge's recommendation that former Whigs and Kentuckians—Powell, in particular—be included in Buchanan's cabinet went unheeded.[132] Kentuckians James B. Clay and Cassius M. Clay were offered diplomatic missions to Berlin and Peru, respectively, but both declined.[133] Buchanan often asked Breckinridge to receive and entertain foreign dignitaries, but in 1858, Breckinridge declined Buchanan's request that he resign and take the again-vacant position as U.S. Minister to Spain.[134] The only private meeting between the two occurred near the end of Buchanan's term, when the president summoned Breckinridge to get his advice on whether to issue a proclamation declaring a day of "Humiliation and Prayer" over the divided state of the nation; Breckinridge affirmed that Buchanan should make the proclamation.[135]

As vice president, Breckinridge was tasked with presiding over the debates of the Senate. In an early address to that body, he promised, "It shall be my constant aim, gentlemen of the Senate, to exhibit at all times, to every member of this body, the courtesy and impartiality which are due to the representatives of equal States."[136] Historian Lowell H. Harrison wrote that, while Breckinridge fulfilled his promise to the satisfaction of most, acting as moderator limited his participation in debate.[33] Five tie-breaking votes provided a means of expressing his views. Economic motivations explained two—forcing an immediate vote on a codfishing tariff and limiting military pensions to $50 per month ($1760.77 in present-day currency).[137] A third cleared the floor for a vote on Douglas's motion to admit Oregon to the Union, and a fourth defeated Johnson's Homestead Bill.[138] The final vote effected a wording change in a resolution forbidding constitutional amendments that empowered Congress to interfere with property rights.[139] The Senate's move from the Old Senate Chamber to a more spacious one on January 4, 1859, provided another opportunity.[33] Afforded the chance to make the last address in the old chamber, Breckinridge encouraged compromise and unity among the states to resolve sectional conflicts.[33]

Despite irregularities in the approval of the Lecompton Constitution by Kansas voters, Breckinridge agreed with Buchanan that it was legitimate, but he kept his position secret, and some believed he agreed with his friend, Stephen Douglas, that Lecompton was invalid.[140] Breckinridge's absence from the Senate during debate on admitting Kansas to the Union under Lecompton seemed to confirm this, but his leave—to take his wife from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where she was recovering from an illness, to Washington, D.C.—had been planned for months.[141] The death of his grandmother, Polly Breckinridge, prompted him to leave earlier than planned.[142] During his absence, both houses of Congress voted to re-submit the Lecompton Constitution to Kansas voters for approval.[143] On resubmission, it was overwhelmingly rejected.[144]

By January 1859, friends knew Breckinridge desired the U.S. Senate seat of John J. Crittenden, whose term expired on March 3, 1861.[33][145] The General Assembly would elect Crittenden's successor in December 1859, so Breckinridge's election would not affect any presidential aspirations he might harbor.[145] Democrats chose Breckinridge's friend Beriah Magoffin over Linn Boyd as their gubernatorial nominee, bolstering Breckinridge's chances for the senatorship, the presidency, or both.[146] Boyd was expected to be Breckinridge's chief opponent for the Senate, but he withdrew on November 28, citing ill health, and died three weeks later.[147] The Democratic majority in the General Assembly elected Breckinridge to succeed Crittenden by a vote of 81 to 53 over Joshua Fry Bell, whom Magoffin had defeated for the governorship in August.[147]

After Minnesota's admission to the Union in May 1858, opponents accused Breckinridge of rigging a random draw so that his friend, Henry Rice, would get the longer of the state's two Senate terms.[148] Senate Secretary Asbury Dickins blunted the charges, averring that he alone handled the instruments used in the drawing.[148] Republican Senator Solomon Foot closed a special session of the Thirty-sixth Congress in March 1859 by offering a resolution praising Breckinridge for his impartiality; after the session, the Republican-leaning New York Times noted that while the star of the Buchanan administration "falls lower every hour in prestige and political consequence, the star of the Vice President rises higher".[149]

Presidential election of 1860

[edit]Breckinridge's lukewarm support for Douglas in his 1858 senatorial re-election bid against Abraham Lincoln convinced Douglas that Breckinridge would seek the Democratic presidential nomination, but in a January 1860 letter to his uncle, Breckinridge averred he was "firmly resolved not to".[150] Douglas's political enemies supported Breckinridge, and Buchanan reluctantly dispensed patronage to Breckinridge allies, further alienating Douglas.[150] After Breckinridge left open the possibility of supporting a federal slave code in 1859, Douglas wrote to Robert Toombs that he would support his enemy and fellow Georgian Alexander H. Stephens for the nomination over Breckinridge, although he would vote for Breckinridge over any Republican in the general election.[151]

Nomination

[edit]

Breckinridge asked James Clay to protect his interests at the 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston, South Carolina.[152] Clay, Lazarus Powell, William Preston, Henry Cornelius Burnett, and James B. Beck desired to nominate Breckinridge for president, but in a compromise with Kentucky's Douglas backers, the delegation went to Charleston committed to former Treasury Secretary James Guthrie of Louisville.[150][152] Fifty Southern Democrats, upset at the convention's refusal to include slavery protection in the party's platform, walked out of the convention; the remaining delegates decided that nominations required a two-thirds majority of the original 303 delegates.[153][154] For 35 ballots, Douglas ran well ahead of Guthrie but short of the needed majority.[150] Arkansas's lone remaining delegate nominated Breckinridge, but Beck asked that the nomination be withdrawn because Breckinridge refused to compete with Guthrie.[153] Twenty-one more ballots were cast, but the convention remained deadlocked.[150] On May 3, the convention adjourned until June 18 in Baltimore, Maryland.[155]

Breckinridge's communication with his supporters between the meetings indicated greater willingness to become a candidate, but he instructed Clay to nominate him only if his support exceeded Guthrie's.[156] Many believed that Buchanan supported Breckinridge, but Breckinridge wrote to Beck that "The President is not for me except as a last necessity, that is to say not until his help will not be worth a damn."[156][157] After a majority of the delegates, most of them Douglas supporters, voted to replace Alabama and Louisiana's walk-out delegates with new, pro-Douglas men in Baltimore, Virginia's delegation led another walk-out of Southern Democrats and Buchanan-controlled delegates from the northeast and Pacific coast; 105 delegates, including 10 of Kentucky's 24, left, and the remainder nominated Douglas.[158] The walk-outs held a rival nominating convention, styled the National Democratic Convention, at the Maryland Institute in Baltimore.[159] At that convention on June 23, Massachusetts' George B. Loring nominated Breckinridge for president, and he received 81 of the 105 votes cast, the remainder going to Daniel S. Dickinson of New York.[158] Oregon's Joseph Lane was nominated for vice-president.[5]

Breckinridge told Beck he would not accept the nomination because it would split the Democrats and ensure the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln.[160] On June 25, Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis proposed that Breckinridge should accept the nomination; his strength in the South would convince Douglas that his own candidacy was futile.[161] Breckinridge, Douglas, and Constitutional Unionist John Bell would withdraw, and Democrats could nominate a compromise candidate.[161] Breckinridge accepted the nomination, but maintained that he had not sought it and that he had been nominated "against my expressed wishes".[156][162] Davis's compromise plan failed when Douglas refused to withdraw, believing his supporters would vote for Lincoln rather than a compromise candidate.[163]

Election

[edit]The election effectively pitted Lincoln against Douglas in the North and Breckinridge against Bell in the South.[164] Far from expectant of victory, Breckinridge told Davis's wife, Varina, "I trust I have the courage to lead a forlorn hope."[5][154] Caleb Cushing oversaw the publication of several Breckinridge campaign documents, including a campaign biography and copies of his speeches on the occasion of the Senate's move to a new chamber and his election to the Senate.[165] After making a few short speeches during stops between Washington, D.C. and Lexington, Breckinridge stated that, consistent with contemporary custom, he would make no more speeches until after the election, but the results of an August 1860 special election to replace the deceased clerk of the Kentucky Court of Appeals convinced him that his candidacy could be faltering.[163] He had expressed confidence that the Democratic candidate for the clerkship would win, and "nothing short of a defeat by 6,000 or 8,000 would alarm me for November". Constitutional Unionist Leslie Combs won by 23,000 votes, prompting Breckinridge to make a full-length campaign speech in Lexington on September 5, 1860.[166]

Breckinridge's three-hour speech was primarily defensive; his moderate tone was designed to win votes in the north but risked losing Southern support to Bell.[166][167] He denied charges that he had supported Zachary Taylor over Lewis Cass in 1848, that he had sided with abolitionists in 1849, and that he had sought John Brown's pardon for the Harpers Ferry raid.[166] Reminding the audience that Douglas wanted the Supreme Court to decide the issue of slavery in the territories, he pointed out that Douglas then denounced the Dred Scott ruling and laid out a means for territorial legislatures to circumvent it.[168] Breckinridge supported the legitimacy of secession but insisted it was not the solution to the country's sectional disagreements.[32] In answer to Douglas's charge that there was not "a disunionist in America who is not a Breckinridge man", he challenged the assembled crowd "to point out an act, to disclose an utterance, to reveal a thought of mine hostile to the constitution and union of the States".[38] He warned that Lincoln's insistence on emancipation made him the real disunionist.[38][169]

Breckinridge finished third in the popular vote with 849,781 votes to Lincoln's 1,866,452, Douglas's 1,379,957, and Bell's 588,879.[40] He carried 12 of the 15 Southern states and the border states of Maryland, Delaware and North Carolina but lost his home state to Bell.[40] His greatest support in the Deep South came from areas that opposed secession.[170] Davis pointed out that only Breckinridge garnered nearly equal support from the Deep South, the border states, and the free states of the North.[171] His 72 electoral votes bested Bell's 59 and Douglas's 12, but Lincoln received 180, enough to win the election.[167]

Aftermath

[edit]Three weeks after the election, Breckinridge returned to Washington, D.C., to preside over the Senate's lame duck session.[172] Lazarus Powell, now a senator, proposed a resolution creating a committee of thirteen members to respond to the portion of Buchanan's address regarding the disturbed condition of the country.[173] Breckinridge appointed the members of the committee, which, in Heck's opinion, formed "an able committee, representing every major faction."[173] John J. Crittenden proposed a compromise by which slavery would be forbidden in territories north of parallel 36°30′ north—the demarcation line used in the Missouri Compromise—and permitted south of it, but the committee's five Republicans rejected the proposal.[42] On December 31, the committee reported that it could come to no agreement.[42] Writing to Magoffin on January 6, Breckinridge complained that the Republicans were "rejecting everything, proposing nothing" and "pursuing a policy which ... threatens to plunge the country into ... civil war".[42]

One of Breckinridge's final acts as vice-president was announcing the vote of the Electoral College to a joint session of Congress on February 13, 1861.[174] Rumors abounded that he would tamper with the vote to prevent Lincoln's election.[175] Knowing that some legislators planned to attend the session armed, Breckinridge asked Winfield Scott to post guards in and around the chambers.[175] One legislator raised a point of order, requesting that the guards be ejected, but Breckinridge refused to sustain it; the electoral vote proceeded, and Breckinridge announced Lincoln's election as president.[176] After Lincoln's arrival in Washington, D.C., on February 24, Breckinridge visited him at the Willard Hotel.[177] After making a valedictory address on March 4, he swore in Hannibal Hamlin as his successor as vice president; Hamlin then swore in Breckinridge and the other incoming senators.[178]

U.S. Senate

[edit]Because Republicans controlled neither house of Congress, nor the Supreme Court, Breckinridge did not believe Lincoln's election was a mandate for secession.[179] Ignoring James Murray Mason's contention that no Southerner should serve in Lincoln's cabinet, Breckinridge supported the appointment of Virginian Montgomery Blair as Postmaster General.[180] He also voted against a resolution to remove the names of the senators from seceded states from the Senate roll.[181][note 4]

Working for a compromise that might yet save the Union, Breckinridge opposed a proposal by Ohio's Clement Vallandigham that the border states unite to form a "middle confederacy" that would place a buffer between the U.S. and the seceded states, nor did Breckinridge desire to see Kentucky as the southernmost state in a northern confederacy; its position south of the Ohio River left it too vulnerable to the southern confederacy should war occur.[180] Urging that federal troops be withdrawn from the seceded states, he insisted "their presence can accomplish no good, but will certainly produce incalculable mischief".[182] He warned that, unless Republicans made some concessions, Kentucky and the other border states would also secede.[182]

When the legislative session ended on March 28, Breckinridge returned to Kentucky and addressed the state legislature on April 2, 1861.[182] He urged the General Assembly to push for federal adoption of the Crittenden Compromise and advocated calling a border states convention, which would draft a compromise proposal and submit it to the Northern and Southern states for adoption.[183] Asserting that the states were coequal and free to choose their own course, he maintained that, if the border states convention failed, Kentucky should call a sovereignty convention and join the Confederacy as a last resort.[179][183][184]

The Battle of Fort Sumter, which began the Civil War, occurred days later, before the border states convention could be held.[183] Magoffin called a special legislative session on May 6, and the legislature authorized creation of a six-man commission to decide the state's course in the war.[185] Breckinridge, Magoffin, and Richard Hawes were the states' rights delegates to the conference, while Crittenden, Archibald Dixon, and Samuel S. Nicholas represented the Unionist position.[185] The delegates were only able to agree on a policy of armed neutrality, which Breckinridge believed impractical and ultimately untenable, but preferable to more drastic actions.[185] In special elections held June 20, 1861, Unionists won nine of Kentucky's ten House seats, and in the August 5 state elections, Unionists gained majorities in both houses of the state legislature.[179]

When the Senate convened for a special session on July 4, 1861, Breckinridge stood almost alone in opposition to the war.[186] Labeled a traitor, he was removed from the Committee on Military Affairs.[187][188] He demanded to know what authority Lincoln had to blockade Southern ports or suspend the writ of habeas corpus.[189] He reminded his fellow senators that Congress had not approved a declaration of war and maintained that Lincoln's enlistment of men and expenditure of funds for the war effort were unconstitutional.[189] If the Union could be persuaded not to attack the Confederacy, he predicted that "all those sentiments of common interest and feeling ... might lead to a political reunion founded upon consent".[189] On August 1, he declared that if Kentucky supported Lincoln's prosecution of the war, "she will be represented by some other man on the floor of this Senate."[186] Asked by Oregon's Edward Dickinson Baker how he would handle the secession crisis, he responded, "I would prefer to see these States all reunited upon true constitutional principles to any other object that could be offered me in life ... But I infinitely prefer to see a peaceful separation of these States, than to see endless, aimless, devastating war, at the end of which I see the grave of public liberty and of personal freedom."[190]

In early September, Confederate and Union forces entered Kentucky, ending her neutrality.[186] On September 18, Unionists shut down the pro-Southern Louisville Courier newspaper and arrested former governor Charles S. Morehead, who was suspected of having Confederate sympathies.[191] Learning that Colonel Thomas E. Bramlette was under orders to arrest him, Breckinridge fled to Prestonsburg, Kentucky, where he was joined by Confederate sympathizers George W. Johnson, George Baird Hodge, William E. Simms, and William Preston.[192] The group continued to Abingdon, Virginia, where they took a train to Confederate-held Bowling Green, Kentucky.[192]

On October 2, 1861, the Kentucky General Assembly passed a resolution declaring that neither of the state's U.S. Senators—Breckinridge and Powell—represented the will of the state's citizens and requesting that both resign.[193] Governor Magoffin refused to endorse the resolution, preventing its enforcement.[193] Writing from Bowling Green on October 8, Breckinridge declared, "I exchange with proud satisfaction a term of six years in the Senate of the United States for the musket of a soldier."[186] Later that month, he was part of a convention in Confederate-controlled Russellville, Kentucky, that denounced the Unionist legislature as not representing the will of most Kentuckians and called for a sovereignty convention to be held in that city on November 18.[194] Breckinridge, George W. Johnson, and Humphrey Marshall were named to the planning committee, but Breckinridge did not attend the convention, which created a provisional Confederate government for Kentucky.[194] On November 6, Breckinridge was indicted for treason in a federal court in Frankfort.[186] The Senate passed a resolution formally expelling him on December 2, 1861; Powell was the only member to vote against the resolution, claiming that Breckinridge's statement of October 8 amounted to a resignation, rendering the resolution unnecessary.[193]

Confederate Secretary of War

[edit]Breckinridge served in the Confederate Army from November 2, 1861, until early 1865.[32] In mid-January 1865, Confederate President Jefferson Davis summoned Breckinridge to the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, and rumors followed that Davis would appoint Breckinridge Confederate States Secretary of War, replacing James A. Seddon.[195][196] Breckinridge arrived in Richmond on January 17, and some time in the next two weeks, Davis offered him the appointment.[197] Breckinridge made his acceptance conditional upon the removal of Lucius B. Northrop from his office as Confederate Commissary General.[198] Most Confederate officers regarded Northrop as inept, but Davis had long defended him.[198] Davis relented on January 30, allowing Seddon to replace Northrop with Breckinridge's friend, Eli Metcalfe Bruce, on an interim basis; Breckinridge accepted Davis's appointment the next day.[198]

Some Confederate congressmen were believed to oppose Breckinridge because he had waited so long to join the Confederacy, but his nomination was confirmed unanimously on February 6, 1865.[195][199] At 44 years old, he was the youngest person to serve in the Confederate president's cabinet.[198] Klotter called Breckinridge "perhaps the most effective of those who held that office", but Harrison wrote that "no one could have done much with the War Department at that late date".[167][200] While his predecessors had largely served Davis's interests, Breckinridge functioned independently, assigning officers, recommending promotions, and consulting on strategy with Confederate generals.[200]

Breckinridge's first act as secretary was to meet with assistant secretary John Archibald Campbell, who had opposed Breckinridge's nomination, believing he would focus on a select few of the department's bureaus and ignore the rest.[201] During their conference, Campbell expressed his desire to retain his post, and Breckinridge agreed, delegating many of the day-to-day details of the department's operation to him.[199][202] Breckinridge recommended that Davis appoint Isaac M. St. John, head of the Confederate Nitre and Mining Bureau, as permanent commissary general.[203] Davis made the appointment on February 15, and the flow of supplies to Confederate armies improved under St. John.[203][204] With Confederate ranks plagued by desertion, Breckinridge instituted a draft; when this proved ineffective, he negotiated the resumption of prisoner exchanges with the Union in order to replenish the Confederates' depleted manpower.[205]

By late February, Breckinridge had concluded that the Confederate cause was hopeless.[200] He opposed the use of guerrilla warfare by Confederate forces and urged a national surrender.[32] Meeting with Confederate senators from Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Texas, he urged, "This has been a magnificent epic. In God's name let it not terminate in a farce."[204] In April, with Union forces approaching Richmond, Breckinridge organized the escape of the other cabinet officials to Danville, Virginia.[206] Afterward, he ordered the burning of the bridges over the James River and ensured the destruction of buildings and supplies that might aid the enemy.[199][200] During the surrender of the city, he helped preserve the Confederate government and military records housed there.[32]

After a brief rendezvous with Robert E. Lee's retreating forces at Farmville, Virginia, Breckinridge moved south to Greensboro, North Carolina, where he, Naval Secretary Stephen Mallory, and Postmaster General John Henninger Reagan joined Generals Joseph E. Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard to urge surrender.[207] Davis and Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin initially resisted, but eventually asked Major General William T. Sherman to parley.[208] Johnston and Breckinridge negotiated terms with Sherman, but President Andrew Johnson (who had assumed the presidency on Lincoln's assassination on April 15) rejected them as too generous.[209][210] On Davis' orders, Breckinridge told Johnston to meet Richard Taylor in Alabama, but Johnston, believing his men would refuse to fight any longer, surrendered to Sherman on similar terms to those offered to Lee at Appomattox.[211]

After the failed negotiations, Confederate Attorney General George Davis and Confederate Treasury Secretary George Trenholm resigned.[212] The rest of the Confederate cabinet—escorted by over 2,000 cavalrymen under Basil W. Duke and Breckinridge's cousin William Campbell Preston Breckinridge—traveled southwest to meet Taylor at Mobile.[212] Believing that the Confederate cause was not yet lost, Davis convened a council of war on May 2 in Abbeville, South Carolina, but the cavalry commanders told him that the only cause for which their men would fight was to aid Davis's escape from the country.[213][214] Informed that gold and silver coins and bullion from the Confederate treasury were at the train depot in Abbeville, Breckinridge ordered Duke to load it onto wagons and guard it as they continued southward.[215][216] En route to Washington, Georgia, some members of the cabinet's escort threatened to take their back salaries by force.[215] Breckinridge had intended to wait until their arrival to make the payments, but to avoid mutiny, he dispersed some of the funds immediately.[213] Two brigades deserted immediately after being paid; the rest continued to Washington, where the remaining funds were deposited in a local bank.[217]

Discharging most of the remaining escort, Breckinridge left Washington with a small party on May 5, hoping to distract federal forces from the fleeing Confederate president.[218] Between Washington and Woodstock, the party was overtaken by Union forces under Lieutenant Colonel Andrew K. Campbell; Breckinridge ordered his nephew to surrender while he, his sons Cabell and Clifton, James B. Clay Jr., and a few others fled into the nearby woods.[219] At Sandersville, he sent Clay and Clifton home, announcing that he and the rest of his companions would proceed to Madison, Florida.[220] On May 11, they reached Milltown, Georgia, where Breckinridge expected to rendezvous with Davis, but on May 14, he learned of Davis's capture days earlier.[221]

Later life

[edit]Besides marking the end of the Confederacy and the war, Davis's capture left Breckinridge as the highest-ranking former Confederate still at large.[5] Fearing arrest, he fled to Cuba, Great Britain, and Canada, where he lived in exile.[167] Andrew Johnson issued a proclamation of amnesty for all former Confederates in December 1868, and Breckinridge returned home the following March.[167] Friends and government officials, including President Ulysses S. Grant, urged him to return to politics, but he declared himself "an extinct volcano" and never sought public office again.[5][32] He died of complications from war-related injuries on May 17, 1875.[222]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Loco-foco" was by then a derogatory term used by Whigs to describe the Democratic Party; see locofocos.

- ^ "Democracy" here refers to the U.S. Democratic Party, not the form of government.

- ^ The role of White House hostess was typically filled by the First Lady (the president's wife), but Buchanan was unmarried. His niece, Harriet Lane, functioned as the mansion's official hostess during his term.

- ^ For a list of individuals expelled from the U.S. Senate, see List of United States senators expelled or censured. For a list of seceded states and their dates of secession, see Confederate States of America#States.

References

[edit]- ^ Klotter, pp. 96–97

- ^ Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 97

- ^ Klotter, p. 108

- ^ a b Heck, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f "John Cabell Breckinridge". Encyclopedia of World Biography

- ^ a b Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 103

- ^ Heck, pp. 11, 13

- ^ Davis, p. 27

- ^ a b Heck, p. 14

- ^ Heck, p. 15

- ^ a b Davis, p. 19

- ^ a b c Heck, p. 163

- ^ a b Davis, p. 5

- ^ Davis, p. 7

- ^ Davis, p. 8

- ^ a b Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 109

- ^ Davis, p. 17

- ^ a b Davis, pp. 14, 17

- ^ a b c d e f g Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 113

- ^ a b Davis, p. 16

- ^ Davis, p. 21

- ^ a b Davis, p. 43

- ^ Davis, pp. 19, 44

- ^ a b Davis, p. 47

- ^ Heck, p. 31

- ^ a b "John Cabell Breckinridge, 14th Vice President (1857–1861)". United States Senate

- ^ Davis, p. 59

- ^ Heck, pp. 163–164

- ^ Klotter in The Kentucky Encyclopedia, p. 117

- ^ a b c d Heck, p. 33

- ^ a b c d e f g h Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 104

- ^ a b c d e f Current, "John C. Breckinridge"

- ^ a b c d e f Harrison, p. 127

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 208

- ^ Heck, p. 80

- ^ Davis, p. 209

- ^ Heck, p. 167

- ^ a b c Harrison and Klotter, p. 184

- ^ Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 117

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 245

- ^ Davis, p. 250

- ^ a b c d Heck, p. 95

- ^ Davis, p. 251

- ^ Davis, p. 253

- ^ Davis, p. 30

- ^ Heck, p. 19

- ^ a b Davis, p. 31

- ^ a b Heck, p. 20

- ^ a b Heck, p. 26

- ^ a b Heck, p. 27

- ^ Davis, p. 45

- ^ a b c d Davis, p. 46

- ^ Heck, p. 29

- ^ Davis, pp. 46, 48

- ^ a b c d Heck, p. 30

- ^ Davis, p. 48

- ^ Davis, pp. 47–48

- ^ a b Davis, p. 49

- ^ Davis, p. 50

- ^ Heck, p. 32

- ^ a b Davis, p. 51

- ^ Davis, p. 52

- ^ Davis, p. 53

- ^ a b c d e f Harrison, p. 126

- ^ a b Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 105

- ^ a b c Heck, p. 34

- ^ Davis, pp. 55–56

- ^ Davis, pp. 58–59

- ^ a b c d Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 107

- ^ a b Davis, p. 61

- ^ Heck, p. 40

- ^ Davis, pp. 62–63

- ^ Davis, pp. 65–66

- ^ Davis, p. 66

- ^ Davis, pp. 66–67

- ^ Davis, p. 67

- ^ a b c d Davis, p. 68

- ^ a b c d e Heck, p. 39

- ^ Davis, p. 69

- ^ Davis, p. 70

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 71

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 72

- ^ a b Davis, p. 73

- ^ Heck, pp. 37–38

- ^ Davis, p. 76

- ^ Davis, pp. 76–77

- ^ Davis, p. 77

- ^ Davis, p. 81

- ^ a b Davis, p. 82

- ^ a b Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 106

- ^ a b Davis, p. 80

- ^ a b Davis, p. 91

- ^ Davis, p. 90

- ^ a b Heck, p. 35

- ^ a b Heck, p. 37

- ^ Davis, pp. 98–99

- ^ Davis, p. 121

- ^ Davis, p. 100

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 101

- ^ Davis, pp. 104–105

- ^ Heck, pp. 42, 55

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 119

- ^ a b Heck, p. 45

- ^ a b Davis, p. 128

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 129

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 124

- ^ Davis, p. 126

- ^ Davis, p. 127

- ^ Davis, pp. 127–128

- ^ a b Heck, p. 48

- ^ Heck, p. 50

- ^ Heck, pp. 50–51

- ^ Heck, p. 51

- ^ Heck, p. 53

- ^ Heck, pp. 53–54

- ^ Davis, p. 137

- ^ Davis, p. 138

- ^ Davis, p. 139

- ^ Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 110

- ^ Davis, p. 144

- ^ Davis, p. 145

- ^ Heck, p. 59

- ^ Heck, p. 60

- ^ a b Davis, p. 158

- ^ a b Davis, p. 159

- ^ Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 111

- ^ Heck, p. 63

- ^ a b Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 112

- ^ a b Heck, p. 67

- ^ Heck, p. 68

- ^ Davis, p. 171

- ^ Davis, p. 168

- ^ Davis, pp. 169–170

- ^ Davis, pp. 181, 192

- ^ Davis, pp. 250–251

- ^ Davis, p. 167

- ^ Davis, p. 184

- ^ Davis, pp. 184, 195

- ^ Davis, p. 259

- ^ Davis, pp. 178, 182

- ^ Davis, pp. 182–184

- ^ Davis, p. 182

- ^ Davis, p. 183

- ^ Davis, p. 190

- ^ a b Heck, p. 77

- ^ Heck, p. 78

- ^ a b Heck, p. 79

- ^ a b Davis, p. 185

- ^ Davis, p. 197

- ^ a b c d e Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 114

- ^ Davis, pp. 212–213

- ^ a b Heck, p. 82

- ^ a b Davis, p. 218

- ^ a b Harrison and Klotter, p. 183

- ^ Heck, p. 83

- ^ a b c Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 115

- ^ Davis, p. 212

- ^ a b Heck, p. 84

- ^ Melzer, p. 218

- ^ Davis, p. 224

- ^ a b Davis, p. 225

- ^ Heck, p. 85

- ^ a b Heck, p. 86

- ^ Harrison, p. 128

- ^ Davis, p. 233

- ^ a b c Heck, p. 87

- ^ a b c d e Klotter in The Kentucky Encyclopedia, p. 118

- ^ Heck, p. 88

- ^ Heck, p. 89

- ^ Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, pp. 117–118

- ^ Davis, p. 246

- ^ Heck, p. 92

- ^ a b Heck, p. 94

- ^ Harrison and Klotter, p. 185

- ^ a b Davis, p. 257

- ^ Davis, p. 258

- ^ Heck, p. 97

- ^ Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 118

- ^ a b c Harrison, p. 129

- ^ a b Davis, p. 261

- ^ Davis, p. 262

- ^ a b c Heck, p. 98

- ^ a b c Harrison and Klotter, p. 187

- ^ Davis, p. 264

- ^ a b c Harrison and Klotter, p. 188

- ^ a b c d e Harrison, p. 130

- ^ Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 120

- ^ Davis, p. 268

- ^ a b c Klotter, p. 119

- ^ Davis, p. 276

- ^ Davis, p. 285

- ^ a b Heck, p. 104

- ^ a b c Davis, p. 296

- ^ a b Harrison and Klotter, p. 192

- ^ a b Heck, p. 132

- ^ Davis, p. 478

- ^ Davis, pp. 478–479

- ^ a b c d Davis, p. 480

- ^ a b c Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 128

- ^ a b c d Harrison, p. 131

- ^ Davis, pp. 485–486

- ^ Davis, p. 486

- ^ a b Davis, p. 487

- ^ a b Heck, p. 133

- ^ Davis, p. 491

- ^ Heck, p. 134

- ^ Davis, p. 507

- ^ Heck, p. 135

- ^ Heck, pp. 135–136

- ^ Harrison, p. 138

- ^ Heck, p. 136

- ^ a b Davis, p. 518

- ^ a b Heck, p. 137

- ^ Davis, pp. 519–520

- ^ a b Klotter in The Breckinridges of Kentucky, p. 129

- ^ Davis, p. 520

- ^ Heck, pp. 137–138

- ^ Heck, p. 138

- ^ Davis, p. 524

- ^ Davis, p. 525

- ^ Davis, p. 528

- ^ Heck, p. 160

Bibliography

[edit]- Current, Richard Nelson, ed. (1993). "John C. Breckinridge". Encyclopedia of the Confederacy. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Davis, William C. (2010). Breckinridge: Statesman, Soldier, Symbol. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8071-0068-4.

- Harrison, Lowell H. (April 1973). "John C. Breckinridge: Nationalist, Confederate, Kentuckian". Filson Club History Quarterly. 47 (2). Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- Harrison, Lowell H.; James C. Klotter (1997). A New History of Kentucky. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2008-9.

- Heck, Frank H. (1976). Proud Kentuckian: John C. Breckinridge, 1821–1875. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-0217-7.

- "John Cabell Breckinridge". Dictionary of American Biography. New York City, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1936. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- "John Cabell Breckinridge". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Vol. 22. Detroit, Michigan: Gale. 2002. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- "John Cabell Breckinridge, 14th Vice President (1857–1861)". United States Senate. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Klotter, James C. (1986). The Breckinridges of Kentucky. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-9165-2.

- Klotter, James C. (1992). "Breckinridge, John Cabell". In John E. Kleber (ed.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-1772-0. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- Melzer, Dorothy Garrett (July 1958). "Mr. Breckinridge Accepts". Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 56 (3).