Nix (moon)

Enhanced color image of Nix, taken by New Horizons | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Hal A. Weaver et al.[a] |

| Discovery date | 15 May 2005 |

| Designations | |

Designation | Pluto II[1] |

| Pronunciation | /ˈnɪks/ |

Named after | Nyx |

| S/2005 P 2 | |

| Adjectives | Nictian (/ˈnɪktiən/) |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| 48694±3 km | |

| Eccentricity | 0.002036±0.000050 |

| 24.85463±0.00003 d | |

| Inclination | 0.133°±0.008° (122.53°±0.008° to Pluto's orbit) |

| Satellite of | Pluto |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 49.8 × 33.2 × 31.1 km[3] (Geometric mean of 37 km) |

| Mass | (2.60±0.52)×1016 kg[4]: 10 |

Mean density | 1.031±0.204 g/cm3[4]: 10 |

| ≈ 0.0028 m/s2 at longest axis to ≈ 0.0072 m/s2 at poles | |

| ≈ 0.0118 km/s at longest axis to ≈ 0.0149 km/s at poles | |

| 1.829±0.009 d[5]: 3 chaotic[6] (decreased by 10% between discovery and flyby)[7] | |

| 123°±10° (to Pluto–Charon orbit)[8]: 11 48°±10° (to celestial equator)[b] | |

North pole right ascension | 350°±10°[5]: 3 |

North pole declination | 42°±10°[5]: 3 |

| Albedo | 0.56±0.05[5]: 3 |

| 23.38–23.7 (measured)[9] | |

| 8.28[5]: 2 | |

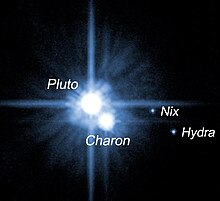

Nix is a natural satellite of Pluto, with a diameter of 49.8 km (30.9 mi) across its longest dimension.[3] It was discovered along with Pluto's outermost moon Hydra on 15 May 2005 by astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope,[1] and was named after Nyx, the Greek goddess of the night.[10] Nix is the third moon of Pluto by distance, orbiting between the moons Styx and Kerberos.[11]

Nix was imaged along with Pluto and its other moons by the New Horizons spacecraft as it flew by the Pluto system in July 2015.[12] Images from the New Horizons spacecraft reveal a large reddish area on Nix that is likely an impact crater.[13]

Discovery

[edit]

Nix was independently discovered by Max Mutchler and Andrew Steffl, members of the Pluto Companion Search Team, using the Hubble Space Telescope.[10] The New Horizons team had suspected that Pluto and its moon Charon might be accompanied by other moons, hence they used the Hubble Space Telescope to search for faint moons around Pluto in 2005.[14] Since Nix's brightness is about 5,000 times fainter than Pluto, long exposure images were taken in order to find it.[15]

The discovery images were taken on 15 May 2005 and 18 May 2005. The discoveries were announced on 31 October 2005, after confirmation by precovering archival Hubble images of Pluto from 2002.[16] The two newly announced moons of Pluto were subsequently provisionally designated S/2005 P 1 for Hydra and S/2005 P 2 for Nix. The moons were informally referred to as "P1" and "P2", respectively by the discovery team.[17]

Naming

[edit]

The name Nix was approved by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) and was announced on 21 June 2006 along with the naming of Hydra in the IAU Circular 8723.[18] Nix was named after Nyx, the Greek goddess of darkness and night and mother of Charon, the ferryman of Hades in Greek mythology. The two newly named moons were intentionally named that the order of their initials N and H honors the New Horizons mission to Pluto, similarly to how the first two letters of Pluto's name honors Percival Lowell.[19][14] The original proposal for the naming of Nix was to use the classical spelling Nyx, but to avoid confusion with the asteroid 3908 Nyx, the spelling was changed to Nix, the Coptic spelling of the name.[19] The adjectival form of the name is Nictian (cf. Russian Никта Nikta).

The names of features on the bodies in the Pluto system are related to mythology and the literature and history of exploration. In particular, the names of features on Nix must be related to deities of the night from literature, mythology, and history.[20]

Origin

[edit]Pluto's smaller moons, including Nix, were thought to have formed from debris ejected from a massive collision between Pluto and another Kuiper belt object, similarly to how the Moon is believed to have formed from debris ejected by a large collision of Earth.[21] The ejecta from the collision would then coalesce into the moons of Pluto.[22] However, the collisional hypothesis cannot explain how Nix maintained its highly reflective surface.[23]

Physical characteristics

[edit]Nix has an elongated shape, with its longest axis measured at 49.8 km (30.9 mi) across and its shortest axis 31.1 km (19.3 mi) across. This gives Nix the measured dimensions of 49.8 km × 33.2 km × 31.1 km (30.9 mi × 20.6 mi × 19.3 mi).[3] It is the third-largest moon of Pluto, being slightly smaller than Hydra.

Early research appeared to show that the surface of Nix is reddish in color.[24] Contrary to this, other studies show that Nix is spectrally neutral, similar to the small moons of Pluto.[9][5] The neutral spectrum of Nix signifies that water ice is present on its surface.[23] Nix also appeared to vary in brightness and albedo, or reflectivity.[9] The brightness fluctuations were thought to be caused by areas with different albedos on the surface of Nix.[9] Images of Nix from the New Horizons spacecraft show a large reddish area approximately 18 km (11 mi) across, which could explain the two conflicting measurements of Nix's surface color.[12][25]

The reddish area is thought to be a large impact crater where the reddish material was ejected from underneath Nix's water ice layer and deposited on its surface.[13] In this case, Nix would likely have regoliths originating from the impact.[5] Another explanation suggests that the reddish material may have originated from a collision with Nix and another object with a different composition. However, there were no significant color variations on other impact craters on Nix.[5]

The water ice present on the surface of Nix is responsible for its high reflectivity.[12][23] Trace amounts of frozen methane may be also present on the surface of Nix, and could be responsible for the presence of reddish material, likely tholins, on its surface.[12] In this case, tholins on the surface of Nix may have originated from the reaction of methane with ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.[12] Derived from crater counting data from New Horizons, the age of Nix's surface is estimated to be at least four billion years old.[26][5]

Rotation

[edit]

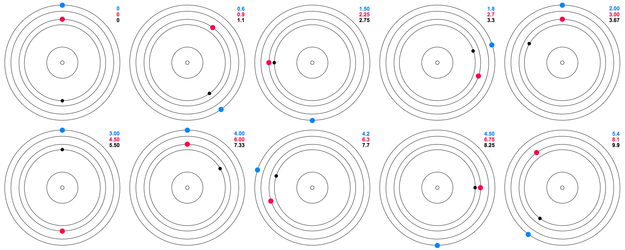

Nix is not tidally locked and tumbles chaotically similarly to all smaller moons of Pluto; the moon's axial tilt and rotation period vary greatly over short timescales.[22] Due to the chaotic rotation of Nix, it can occasionally flip its entire rotational axis.[27] The varying gravitational influences of Pluto and Charon as they orbit their barycenter causes the chaotic tumbling of Pluto's small moons, including Nix.[22] The chaotic tumbling of Nix is also strengthened by its elongated shape, which creates torques that act on the object.[22][2] At the time of the New Horizons flyby, Nix was rotating with a period of 43.9 hours retrograde to Pluto's equator with an axial tilt of 132 degrees — it was rotating backwards in relation to its orbit around Pluto.[23] The rotation rate of Nix had increased by 10 percent since Nix was discovered.[23]

Orbit

[edit]Nix orbits the Pluto-Charon barycenter at a distance of 48,694 km (30,257 mi), between the orbits of Styx and Kerberos.[11] All of Pluto's moons including Nix have very circular orbits that are coplanar to Charon's orbit; the moons of Pluto have very low orbital inclinations to Pluto's equator.[28][29] The nearly circular and coplanar orbits of Pluto's moons suggest that they may have gone through tidal evolutions since their formation.[28] At the time of the formation of Pluto's smaller moons, Nix may have had a more eccentric orbit around the Pluto-Charon barycenter.[30] The present circular orbit of Nix may have been caused by Charon's tidal damping of the eccentricity of Nix's orbit, through tidal interactions. The mutual tidal interactions of Charon on Nix's orbit would cause Nix to transfer its orbital eccentricity to Charon, thus causing the orbit of Nix to gradually become more circular over time.[30]

Nix has an orbital period of 24.8546 days and its orbit is resonant with other moons of Pluto.[2] Nix is in a 3:2 orbital resonance with Hydra, and a 9:11 resonance with Styx (the ratios represent numbers of orbits completed per unit time; the period ratios are the inverses).[2][31] As a result of this "Laplace-like" 3-body resonance, it has conjunctions with Styx and Hydra in a 2:3 ratio.

Nix's orbital period is close to a 1:4 orbital resonance with Charon, with a timing discrepancy of 2.8%; there is no active resonance.[2][24] A hypothesis explaining such a near-resonance is that the resonances originated before the outward migration of Charon following the formation of all five known moons, and is maintained by the periodic local fluctuation of 9 percent in the Pluto–Charon gravitational field strength.[c]

Exploration

[edit]The New Horizons spacecraft visited the Pluto system and photographed Pluto and its moons during its flyby on 14 July 2015. Of Pluto's smaller moons, only Nix and Hydra were imaged at resolutions high enough for surface features to be visible.[23] Prior to the flyby of the Pluto system, measurements of Nix's size were performed by the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager on board New Horizons, initially estimating Nix to be about 35 km (22 mi) in diameter.[32] The first detailed images of Nix taken by New Horizons from a distance of about 231,000 km (144,000 mi) were downlinked, or received from the spacecraft on 18 July 2015 and released to the public on 21 July 2015.[25] With an image resolution 3 km (1.9 mi) per pixel, Nix's shape was often referred to as a "jelly bean" shape.[25] Enhanced color images from the Ralph MVIC instrument of New Horizons show a reddish region on its surface.[25] From those images, another accurate measurement of Nix's dimensions was made, giving the approximate dimensions of 42 km × 36 km (26 mi × 22 mi).[25]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The full list of discoverers includes H. A. Weaver, S. A. Stern, M. J. Mutchler, A. J. Steffl, M. W. Buie, W. J. Merline, J. R. Spencer, E. F. Young, and L. A. Young.[1]

- ^ Given Nix's rotational north pole declination of +42°,[5]: 5 subtracting this angle from the north celestial pole of +90° gives the inclination with respect to the celestial equator: i = +90° – (+42°) = +48°.

- ^ The instantaneous force in the Pluto–Charon–Nix alignment case is 9.46% larger than in the quadrature case (where Nix is 90° from the Pluto–Charon axis); the Charon–Pluto–Nix case is almost exactly halfway between these values. In Buie et al., the quote is "The gravitational force exerted by Pluto on either P1 or P2 varies by roughly 15% (peak-to-peak)." Pluto's gravitational pull, by itself, varies by 18% for Nix and 13% for Hydra.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. International Astronomical Union (IAU) Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN). Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Showalter, M. R.; Hamilton, D. P. (3 June 2015). "Resonant interactions and chaotic rotation of Pluto's small moons". Nature. 522 (7554): 45–49. Bibcode:2015Natur.522...45S. doi:10.1038/nature14469. PMID 26040889. S2CID 205243819.

- ^ a b c Verbiscer, A. J.; Porter, S. B.; Buratti, B. J.; Weaver, H. A.; Spencer, J. R.; Showalter, M. R.; Buie, M. W.; Hofgartner, J. D.; Hicks, M. D.; Ennico-Smith, K.; Olkin, C. B.; Stern, S. A.; Young, L. A.; Cheng, A. (2018). "Phase Curves of Nix and Hydra from the New Horizons Imaging Cameras". The Astrophysical Journal. 852 (2): L35. Bibcode:2018ApJ...852L..35V. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aaa486.

- ^ a b Porter, Simon B.; Canup, Robin M. (July 2023). "Orbits and Masses of the Small Satellites of Pluto". The Planetary Science Journal. 4 (7): 14. arXiv:2307.04848. Bibcode:2023PSJ.....4..120P. doi:10.3847/PSJ/acde77. 120.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Weaver, H. A.; Buie, M. W.; Buratti, B. J.; Grundy, W. M.; Lauer, T. R.; Olkin, C. B.; et al. (March 2016). "The Small Satellites of Pluto as Observed by New Horizons". Science. 351 (6279): 5. arXiv:1604.05366. Bibcode:2016Sci...351.0030W. doi:10.1126/science.aae0030. PMID 26989256. S2CID 206646188. aae0030.

- ^ Northon, Karen (3 June 2015). "NASA's Hubble Finds Pluto's Moons Tumbling in Absolute Chaos".

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily. "DPS 2015: Pluto's small moons Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra [UPDATED]". www.planetary.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Weaver, H. A.; Buie, M. W.; Buratti, B. J.; Grundy, W. M.; Lauer, T. R.; Olkin, C. B.; et al. (March 2016). "Supplementary Materials for The Small Satellites of Pluto as Observed by New Horizons". Science. 351 (6279): 25. arXiv:1604.05366. Bibcode:2016Sci...351.0030W. doi:10.1126/science.aae0030. PMID 26989256. S2CID 206646188. aae0030.

- ^ a b c d Stern, S. A.; Mutchler, M. J.; Weaver, H. A.; Steffl, A. J. (2006). "The Positions, Colors, and Photometric Variability of Pluto's Small Satellites from HST Observations 2005–2006". Astronomical Journal. 132 (3): 1405–1414. arXiv:astro-ph/0605014. Bibcode:2006AJ....132.1405S. doi:10.1086/506347. S2CID 14360964.

- ^ a b "Pluto and Its Moons: Charon, Nix and Hydra". www.nasa.gov. NASA. 23 June 2006. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b Stern, S. A.; Bagenal, F.; Ennico, K.; Gladstone, G. R.; et al. (15 October 2015). "The Pluto system: Initial results from its exploration by New Horizons". Science. 350 (6258): aad1815. arXiv:1510.07704. Bibcode:2015Sci...350.1815S. doi:10.1126/science.aad1815. PMID 26472913. S2CID 1220226.

- ^ a b c d e Cain, Fraser (3 September 2015). "Pluto's Moon Nix". www.universetoday.com. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b Porter, Simon (5 October 2015). "Pluto's Small Moons Nix and Hydra". blogs.nasa.gov. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b Stern, Alan; Grinspoon, David (1 May 2018). "Chapter 7: Bringing It All Together". Chasing New Horizons: Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto. Picador. ISBN 978-1-250-09896-2.

- ^ "Nix In Depth". solarsystem.nasa.gov. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "NASA's Hubble Reveals Possible New Moons Around Pluto". www.hubblesite.org. 31 October 2005.

- ^ "IAU Circular No. 8625". www.cbat.eps.harvard.edu. 31 October 2005. describing the discovery

- ^ IAU Circular No. 8723 naming the moons.

- ^ a b Cain, Fraser (2006). "Pluto's New Moons are Named Nix and Hydra". www.universetoday.com. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "Naming of Astronomical Objects". International Astronomical Union.

- ^ Stern, S. A.; Weaver, H. A.; Steff, A. J.; Mutchler, M. J.; Merline, W. J.; Buie, M. W.; Young, E. F.; Young, L. A.; Spencer, J. R. (23 February 2006). "A giant impact origin for Pluto's small moons and satellite multiplicity in the Kuiper belt" (PDF). Nature. 439 (7079): 946–948. Bibcode:2006Natur.439..946S. doi:10.1038/nature04548. PMID 16495992. S2CID 4400037. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d Northon, Karen (3 June 2015). "NASA's Hubble Finds Pluto's Moons Tumbling in Absolute Chaos". NASA. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Lakdawalla, Emily. "DPS 2015: Pluto's small moons Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ a b Buie, Marc W.; Grundy, William M.; Young, Eliot F.; Young, Leslie A.; Stern, S. Alan (2006). "Orbits and Photometry of Pluto's Satellites: Charon, S/2005 P1, and S/2005 P2". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (1): 290–298. arXiv:astro-ph/0512491. Bibcode:2006AJ....132..290B. doi:10.1086/504422. S2CID 119386667.. a, i, e per JPL (site updated 2008 Aug 25)

- ^ a b c d e "New Horizons Captures Two of Pluto's Smaller Moons". NASA. 21 July 2015.

- ^ Woo, M. Y.; Lee, M. H. (6 March 2018). "On the Early In Situ Formation of Pluto's Small Satellites". arXiv:1803.02005 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (3 June 2015). "Astronomers Describe the Chaotic Dance of Pluto's Moons". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ a b Steffl, A. J.; Mutchler, M. J.; Weaver, H. A.; Stern, S. A.; et al. (2006). "New Constraints on Additional Satellites of the Pluto System". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (2): 614–619. arXiv:astro-ph/0511837. Bibcode:2006AJ....132..614S. doi:10.1086/505424. S2CID 10547358.(Final preprint)

- ^ Stern, S. A.; Mutchler, M. J.; Weaver, H. A.; Steffl, A. J. (2008). "On the Origin of Pluto's Minor Moons, Nix and Hydra". arXiv:0802.2951 [astro-ph].

- ^ a b Stern, S. A.; Mutchler, M. J.; Weaver, H. A.; Steffl, A. J. (2008). "The Effect of Charon's Tidal Damping on the Orbits of Pluto's Three Moons". arXiv:0802.2939 [astro-ph].

- ^ Witze, Alexandra (2015). "Pluto's moons move in synchrony". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17681. S2CID 134519717.

- ^ "How Big Is Pluto? New Horizons Settles Decades-Long Debate". NASA. 13 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

External links

[edit]- Background Information Regarding Our Two Newly Discovered Satellites of Pluto – The discoverers' website

- NASA's Hubble Reveals Possible New Moons Around Pluto – Hubble press release

- Nix In Depth – NASA Solar System Exploration