Placebo in history

The word placebo was used in a medicinal context in the late 18th century to describe a "commonplace method or medicine" and in 1811 it was defined as "any medicine adapted more to please than to benefit the patient". Although this definition contained a derogatory implication,[1] it did not necessarily imply that the remedy had no effect.[2]

Placebos have featured in medical use until well into the twentieth century.[3] In 1955 Henry K. Beecher published an influential paper entitled The Powerful Placebo which proposed idea that placebo effects were clinically important.[4] Subsequent re-analysis of his materials, however, found in them no evidence of any "placebo effect".[5]

Etymology

[edit]Placebo is the opening word of the antiphon of vespers in the Office of the Dead, used as a name for the service as a whole. The full sentence, from the Vulgate, is Placebo Domino in regione vivorum 'I will please the Lord in the land of the living', from Psalm 116:9.[6][7] To sing placebo at a funeral came to mean to falsely claim a connection to the deceased to get a share of the funeral meal, and hence a flatterer, and so a deceptive act to please.[1]

Early medical usage

[edit]

In the practice of medicine it had been long understood that, as Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) had expressed it, the physician's duty was to "cure occasionally, relieve often, console always" ("Guérir quelquefois, soulager souvent, consoler toujours"). Accordingly, placebos were widespread in medicine until the 20th century, and were often endorsed as necessary deceptions.[3]

According to Nicholas Jewson, eighteenth century English medicine was gradually moving away from a model in which the patient had considerable interaction with the physician – and, through this consultative relationship, had an equal influence on the physician's therapeutic approach. It was moving towards a paradigm in which the patient became the recipient of a more standardized form of intervention that was determined by the prevailing opinions of the medical profession of the day.[8]

Jewson characterized this as parallel to the changes that were taking place in the manner in which medical knowledge was being produced; namely, a transition from "bedside medicine", through to "hospital medicine", and finally to "laboratory medicine".[9]

The last vestiges of the "consoling" approach to treatment were the prescription of morale-boosting and pleasing remedies, such as the "sugar pill", electuary or pharmaceutical syrup; all of which had no known pharmacodynamic action, even at the time. Those doctors who provided their patients with these sorts of morale-boosting therapies (which, while having no pharmacologically active ingredients, provided reassurance and comfort) did so either to reassure their patients while the Vis medicatrix naturae (i.e., "the healing power of nature") performed its normalizing task of restoring them to health, or to gratify their patients' need for an active treatment.[citation needed]

In 1811, Hooper's Quincy's Lexicon–Medicum defined placebo as "an epithet given to any medicine adapted more to please than benefit the patient".

Early implementations of placebo controls date back to 16th-century Europe with Catholic efforts to discredit exorcisms. Individuals who claimed to be possessed by demonic forces were given false holy objects. If the person reacted with violent contortions, it was concluded that the possession was purely imagination.[10]

Use of the placebo effect as a medical treatment has been controversial throughout history, and was common until the mid twentieth century.[3] In 1903 Richard Cabot concluded that it should be avoided because it is deceptive. Newman points out the "placebo paradox" – it may be unethical to use a placebo, but also unethical "not to use something that heals". He suggests to solve this dilemma by appropriating the meaning response in medicine, that is make use of the placebo effect, as long as the "one administering... is honest, open, and believes in its potential healing power".[11]

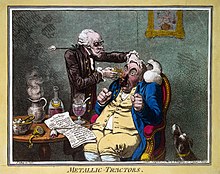

John Haygarth was the first to investigate the efficacy of the placebo effect in the 18th century.[12] He tested a popular medical treatment of his time, called "Perkins tractors", and concluded that the remedy was ineffectual by demonstrating that the results from a dummy remedy were just as useful as from the alleged "active" remedy.[13]

Émile Coué, a French pharmacist, working as an apothecary at Troyes between 1882 and 1910, also advocated the effectiveness of the "Placebo Effect". He became known for reassuring his clients by praising each remedy's efficiency and leaving a small positive notice with each given medication. His book Self-Mastery Through Conscious Autosuggestion was published in England (1920) and in the United States (1922).

Placebos remained widespread in medicine until the 20th century, and they were sometimes endorsed as necessary deceptions.[3] In 1903, Richard Cabot said that he was brought up to use placebos,[3] but he ultimately concluded by saying that "I have not yet found any case in which a lie does not do more harm than good".[11]

T. C. Graves first defined the "placebo effect" in a published paper in The Lancet in 1920.[original research?][14] He spoke of "the placebo effects of drugs" being manifested in those cases where "a real psychotherapeutic effect appears to have been produced".[15]

Placebo effect

[edit]

The placebo effect of new drugs was known anecdotally in the 18th century, as demonstrated by Michel-Philippe Bouvart's 1780s quip to a patient that she should "take [a remedy] ... and hurry up while it [still] cures."[16] A similar sentiment was expressed by William Heberden in 1803[17] and Armand Trousseau in 1833.[18] It is often attributed to William Osler (1901) but without a precise source, and it does not appear in his publications.[19][20]

The first to recognize and demonstrate the placebo effect was English physician John Haygarth in 1799.[21] He tested a popular medical treatment of his time, called "Perkins tractors", which were metal pointers supposedly able to 'draw out' disease. They were sold at the extremely high price of five guineas, and Haygarth set out to show that the high cost was unnecessary. He did this by comparing the results from dummy wooden tractors with a set of allegedly "active" metal tractors, and published his findings in a book On the Imagination as a Cause & as a Cure of Disorders of the Body.[22]

The wooden pointers were just as useful as the expensive metal ones, showing "to a degree which has never been suspected, what powerful influence upon diseases is produced by mere imagination".[23] While the word placebo had been used since 1772, this is the first real demonstration of the placebo effect.[citation needed]

In modern times the first to define and discuss the "placebo effect" was T.C. Graves, in a 1920 paper in The Lancet.[24] He spoke of "the placebo effects of drugs" being manifested in those cases where "a real psychotherapeutic effect appears to have been produced".[25]

At the Royal London Hospital in 1933, William Evans and Clifford Hoyle experimented with 90 subjects and published studies which compared the outcomes from the administration of an active drug and a dummy simulator ("placebo") in the same trial. The experiment displayed no significant difference between drug treatment and placebo treatment, leading the researchers to conclude that the drug exerted no specific effects in relation to the conditions being treated. [26] A similar experiment was carried out by Harry Gold, Nathaniel Kwit and Harold Otto in 1937, with the use of 700 subjects.[27]

In 1946, the Yale biostatistician and physiologist E. Morton Jellinek described the "placebo reaction" or "response". He probably used the terms "placebo response" and "placebo reaction" as interchangeable.[28] Henry K. Beecher's 1955 paper The Powerful Placebo was the first to use the term "placebo effect", which he contrasts with drug effects. [29] Beecher suggested placebo effects occurred in about 35% of people. However, this paper has been criticized for failing to distinguish the placebo effect from other factors, and for thereby encouraging an inflated notion of the placebo effect,[30] and a 1997 re-analysis failed to support Beecher's conclusions.[5]

In 1955, Henry K. Beecher published a paper entitled The Powerful Placebo. Since that time, 40 years ago, the placebo effect has been considered a scientific fact. Beecher was the first scientist to quantify the placebo effect. [...] This publication is still the most frequently cited placebo reference. Recently Beecher’s article was reanalyzed with surprising results: In contrast to his claim, no evidence was found of any placebo effect in any of the studies cited by him.

— Kienle & Kiene, The Powerful Placebo Effect: Fact or Fiction? [5]

In 1961 Henry K. Beecher concluded[31] that surgeons he categorized as enthusiasts relieved their patients' chest pain and heart problems more than skeptic surgeons.[11]

In 1961 Walter Kennedy introduced the word nocebo to refer to a neutral substance that creates harmful effects in a patient who takes it.[3][32]

Beginning in the 1960s, the placebo effect became widely recognized and placebo-controlled trials became the norm in the approval of new medications.[33]

Dylan Evans argues that placebos are linked with activation of the acute-phase response so will work only on subjective conditions such as pain, swelling, stomach ulcers, depression, and anxiety that are linked to this.[34]

A 2001 systematic review of clinical trials concluded that there was no evidence of clinically important effects, except perhaps in the treatment of pain and continuous subjective outcomes.[4] The authors later published a Cochrane review with similar conclusions (updated as of 2010[update]).[35] Most studies have attributed the difference from baseline until the end of the trial to a placebo effect, but the reviewers examined studies which had both placebo and untreated groups in order to distinguish the placebo effect from the natural progression of the disease.[4]

Placebo observations differ between individuals.[36][37] In the 1950s, there was considerable research to find whether there was a specific personality to those that responded to placebos. The findings could not be replicated[38] and it is now thought to have no effect.[39]

The word obecalp, "placebo" spelled backwards, was coined by an Australian doctor in 1998 when he recognised the need for a freely available placebo.[40] The word is sometimes used to make the use or prescription of fake medicine less obvious to the patient.[41]

It has been suggested that a distinction exists between the placebo effect (which applies to a group) and the placebo response (which is individual).[42]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Shapiro AK (1968). "Semantics of the placebo". Psychiatric Quarterly. 42 (4): 653–95. doi:10.1007/BF01564309. PMID 4891851. S2CID 2733947.

- ^ Kaptchuk TJ (June 1998). "Powerful placebo: the dark side of the randomised controlled trial". The Lancet. 351 (9117): 1722–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10111-8. PMID 9734904. S2CID 34023318.

- ^ a b c d e f de Craen AJ, Kaptchuk TJ, Tijssen JG, Kleijnen J (October 1999). "Placebos and placebo effects in medicine: historical overview". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 92 (10): 511–5. doi:10.1177/014107689909201005. PMC 1297390. PMID 10692902.

- ^ a b c Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC (May 2001). "Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (21): 1594–602. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105243442106. PMID 11372012.

- ^ a b c Kienle GS, Kiene H (December 1997). "The powerful placebo effect: fact or fiction?". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 50 (12): 1311–8. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00203-5. PMID 9449934.

- ^ Psalms 116:9

- ^ Jacobs B (April 2000). "Biblical origins of placebo". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 93 (4): 213–4. doi:10.1177/014107680009300419. PMC 1297986. PMID 10844895.

- ^ Nicholas D. Jewson (September 1974). "Medical Knowledge and the Patronage System in 18th Century England". Sociology. 8 (3): 369–385. doi:10.1177/003803857400800302. S2CID 143768672.

- ^ Nicholas D. Jewson (1976). "The Disappearance of the Sick-Man from Medical Cosmology, 1770–1870". Sociology. 10 (2): 227. doi:10.1177/003803857601000202. S2CID 144097257.

- ^ Beauregard M (2012). Brain Wars: The Scientific Battle Over the Existence of the Mind and the Proof That Will Change the Way We Live Our Lives. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-06-207156-9.

- ^ a b c Newman DH (2008). Hippocrates' Shadow. Scribner. pp. 134–59. ISBN 978-1-4165-5153-9.

- ^ Booth C (August 2005). "The rod of Aesculapios: John Haygarth (1740-1827) and Perkins' metallic tractors". Journal of Medical Biography. 13 (3): 155–61. doi:10.1177/096777200501300310. PMID 16059528. S2CID 208293370.

- ^ Haygarth J (1800). "Of the Imagination, as a Cause and as a Cure of Disorders of the Body; Exemplified by Fictitious Tractors, and Epidemical Convulsions". Bath: Crutwell. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013.

- ^ Graves TC (1920). "Commentary on a case of Hystero-epilepsy with delayed puberty". The Lancet. 196 (5075): 1135. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)00108-8. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Yapko MD (2012). Trancework: An Introduction to the Practice of Clinical Hypnosis. Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-415-88494-5.

- ^ Gaston de Lévis, Souvenirs et portraits, 1780-1789, 1813, p. 240

- ^ William Heberden, Commentaries on the History and Cure of Diseases, London, 1802, p. 40

- ^ Armand Trousseau, Dictionnaire de Médecine, 1833 (page unspecified), as quoted in H. Bernheim, Suggestive Therapeutics, 1889 (page unspecified), quoted in "Competitive Probems in the Drug Industry", U.S. Senate hearings, 1968, p. 3008.

- ^ Charles Murphy, "Guest blog", Emergency Medical Journal, March 30, 2014

- ^ Donald L. Blanchard, Daniel M. Albert, "Historical Excerpts and Quotations Corner", American Academy of Ophthalmology, May 9, 2018

- ^ Booth, C. (2005). "The rod of Aesculapios: John Haygarth (1740-1827) and Perkins' metallic tractors". Journal of Medical Biography. 13 (3): 155–161. doi:10.1177/096777200501300310. PMID 16059528. S2CID 208293370.

- ^ Haygarth, J., Of the Imagination, as a Cause and as a Cure of Disorders of the Body; Exemplified by Fictitious Tractors, and Epidemical Convulsions Archived December 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Crutwell, (Bath), 1800.

- ^ Wootton, David. Bad medicine: Doctors doing harm since Hippocrates. Oxford University Press, 2006.

- ^ T. C. Graves (1920). "Commentary on a case of Hystero-epilepsy with delayed puberty". The Lancet. 196 (5075): 1135. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)00108-8. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Michael D. Yapko (2012). Trancework: An Introduction to the Practice of Clinical Hypnosis. Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 9780415884945.

- ^ Evans W, Hoyle C (1933). "The comparative value of drugs used in the continuous treatment of angina pectoris". Quarterly Journal of Medicine. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Gold H, Kwit NT, Otto H (1937). "The Xanthines (Theobromine and Aminophyllin) in the treatment of cardiac pain". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 108 (26): 2173. doi:10.1001/jama.1937.02780260001001. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Jellinek, E. M. "Clinical Tests on Comparative Effectiveness of Analgesic Drugs", Biometrics Bulletin, Vol.2, No.5, (October 1946), pp. 87–91.

- ^ Henry K. Beecher (1955). "The Powerful Placebo". Journal of the American Medical Association. 159 (17): 1602–6. doi:10.1001/jama.1955.02960340022006. PMID 13271123. S2CID 3173505.

- ^ Finniss DG, Kaptchuk TJ, Miller F, Benedetti F (February 2010). "Biological, clinical, and ethical advances of placebo effects". Lancet. 375 (9715): 686–95. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61706-2. PMC 2832199. PMID 20171404.

- ^ Beecher HK (July 1961). "Surgery as placebo. A quantitative study of bias". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 176 (13): 1102–7. doi:10.1001/jama.1961.63040260007008. PMID 13688614.

- ^ Kennedy, W. P., "The Nocebo Reaction", Medical World, Vol.95, (September 1961), pp. 203–5.

- ^ Kaptchuk TJ (1998). "Intentional ignorance: a history of blind assessment and placebo controls in medicine". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 72 (3): 389–433. doi:10.1353/bhm.1998.0159. PMID 9780448. S2CID 10931827.

- ^ Evans D (2003). Placebo: the belief effect. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-712612-5.

- ^ Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC (January 2010). Hróbjartsson A (ed.). "Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 106 (1): CD003974. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003974.pub3. PMC 7156905. PMID 20091554.

- ^ Benedetti F (March 1996). "The opposite effects of the opiate antagonist naloxone and the cholecystokinin antagonist proglumide on placebo analgesia". Pain. 64 (3): 535–43. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(95)00179-4. PMID 8783319. S2CID 37893726.

- ^ Levine JD, Gordon NC, Bornstein JC, Fields HL (July 1979). "Role of pain in placebo analgesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 76 (7): 3528–31. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76.3528L. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.7.3528. PMC 383861. PMID 291020.

- ^ Doongaji DR, Vahia VN, Bharucha MP (April 1978). "On placebos, placebo responses and placebo responders. (A review of psychological, psychopharmacological and psychophysiological factors). I. Psychological factors". Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 24 (2): 91–7. PMID 364041.

- ^ Hoffman GA, Harrington A, Fields HL (2005). "Pain and the placebo: what we have learned". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 48 (2): 248–65. doi:10.1353/pbm.2005.0054. PMID 15834197. S2CID 1037796.

- ^ Axtens, Michael (August 8, 1998). "Letters to editor: Mind Games". New Scientist.

- ^ E.g. see Gulf War Veteran Gets Placebos Instead Of Real Medicine Archived February 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine or BehindTheMedspeak: Obecalp.

- ^ Hoffman GA, Harrington A, Fields HL (2005). "Pain and the placebo: what we have learned". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 48 (2): 248–65. doi:10.1353/pbm.2005.0054. PMID 15834197. S2CID 1037796.