Pit crater

A pit crater (also called a subsidence crater or collapse crater) is a depression formed by a sinking or collapse of the surface lying above a void or empty chamber, rather than by the eruption of a volcano or lava vent.[1] Pit craters are found on Mercury, Venus,[2][3] Earth, Mars,[4] and the Moon.[5] Pit craters are often found in a series of aligned or offset chains and in these cases, the features is called a pit crater chain. Pit crater chains are distinguished from catenae or crater chains by their origin. When adjoining walls between pits in a pit crater chain collapse, they become troughs. In these cases, the craters may merge into a linear alignment and are commonly found along extensional structures such as fractures, fissures and graben. Pit craters usually lack an elevated rim as well as the ejecta deposits and lava flows that are associated with impact craters.[6][7] Pit craters are characterized by vertical walls that are often full of fissures and vents. They usually have nearly circular openings.[8]

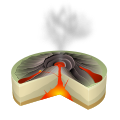

As distinct from impact craters, these craters are not formed from the clashing of bodies or projectiles from space.[6] Rather, they can be formed by a lava explosion from a bottled up volcano (the explosion leaving a shallow caldera) or when the ceiling over a void is not solid enough to prevent collapse of the overlying material. Pit craters can also result from collapse of lava tubes or dikes, or from collapsed magma chambers under loose material.[9]

A newly formed pit crater has steep overhanging sides and is shaped inside like an inverted cone, growing wider closer to the bottom. Over time the overhangs fall into the pit and the crater fills with talus from the collapsing sides and roof. A middle-aged pit crater is cylindrical but its rim will continue to collapse, resulting in the crater's expanding outward until it resembles a funnel or drain—narrower at the bottom than the top.[7][8]

While pit craters and calderas form through similar processes, the former term is usually reserved for smaller features of a mile or less in diameter.[10] The term "pit crater" was coined by C. Wilkes in 1845 to describe craters along Hawaii's East Rift Zone.[11]

Hawaii is known for its volcanoes and pit craters. In 1868 an eyewitness saw more than two-thirds of the basin of Kilauea cave in and fill with a lava lake. This process happened repeatedly. The modern Halema'uma'u Shield began growing and then collapsed into a deep funnel-shaped pit. This pit filled with lava and for 19 years burned continuously, becoming famous as the Hawaiian Fire Pit. In 1924 the lava lake emptied when the walls of the crater cracked and collapsed and filled with water that turned to steam. After a week and a half Halema'uma'u had widened and was 1,700 feet deep. Rocks that were blasted away from the crater can still be seen on the caldera floor.[10]

Devil's Throat (pictured at right) is another good Hawaiian example of a pit crater, especially since we were able to observe its formation through collapse over time. It was first documented by Thomas Jaggar who estimated its dimensions as 15m x 10.5m x 75m. In 1923 William Sinclair was lowered into Devil's Throat on a rope. He found a cavern shaped like an upside down funnel which widened as he approached the bottom. He measured the floor as about 60m in diameter and the crater's depth around 78m. The crater's mouth widened over time and in 2006 the crater's dimensions were measured as 50m x 42m x 49m. This growth is explained by observing pieces of the overhanging roof breaking off and falling to the bottom. These shards gradually piled up on the crater floor, reducing its depth.[12]

The process also happens on the surface of Mars and other terrestrial planets.[6] Features resembling pit craters have been observed on Mercury.

References

[edit]- ^ "Volcanic and Geologic Terms". volcano.und.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ^ Davey; et al. "Pit Crater Chain Clustering in Ganaki Planitia, Venus: Observations and Implications" (PDF). LPSC.

- ^ Davey, S.C.; Ernst, R.E.; Samson, C.; Grosfils, E.B. (8 January 2013). "Hierarchical clustering of pit crater chains on Venus". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 50 (1): 109–126. Bibcode:2013CaJES..50..109D. doi:10.1139/cjes-2012-0054.

- ^ Wyrick; et al. "Pit Crater Chains Across the Solar System" (PDF).

- ^ "Planetary Analog Sites: 3. Pit Craters" (PDF). University of Hawaii. 5 March 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ a b c "Distribution, morphology, and origins of Martian pit crater chains". www.agu.org. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ^ a b Okubo, Chris, and Stephen Martel. "Pit crater formation on Kilauea volcano, Hawaii." Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 86.1-4 (1998):1-18. Print.

- ^ a b Geological Field Guide: Kilauea Volcano. revised edition. Claremont, CA: Hawai'i Natural History Association, 2002. 97. Print

- ^ The Diagram Group, David Lambert & (1998). The Field Guide to Geology (Updated Ed.). MY: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 44–45, 94–95. ISBN 0-8160-3840-6.

- ^ a b Donald W. Hyndman, Richard W. Hazlett & (2005). Roadside Geology Of Hawai'i. Missoula, MN: Mountain Press Publishing. pp. 22–23, 68–70, 72–73, 75, 80–82. ISBN 0-87842-344-3.

- ^ Wilkes, C., 1845. Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition during the years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, and 1842, Vol. 4. Lea and Blanchard, Philadelphia, 180 pp

- ^ USGS. Devil's Throat has evolved into a shadow of its former self, web. 7 Oct 2010 [1]

External links

[edit]- Halema'uma'u Crater

- USGS page on pit craters

- USGS page on Devil's Throat pit crater at the Wayback Machine (archived 14 July 2007)