Matsés language

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (January 2024) |

| Matsés | |

|---|---|

| Mayoruna | |

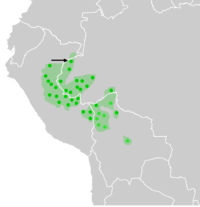

Pano-Tacanan languages (Matses-Mayoruna language is indicated with an arrow) | |

| Native to | Perú, Brazil |

| Ethnicity | Matsés |

Native speakers | 2,200 (2006)[1] |

Panoan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | mcf |

| Glottolog | mats1244 |

| ELP | Matsés |

Matsés, also referred to as Mayoruna in Brazil, is an Indigenous language utilized by the inhabitants of the border regions of Brazil-Peru. A term that hailed from Quechua origin, Mayoruna translates in English to mayu = river; runa = people. Colonizers and missionaries during the 17th century used this term to refer to the Indigenous peoples that occupied the lower Ucayali Region (Amazonian region of Peru), Upper Solimões (upper stretches of the Amazon River in Brazil) and Vale do Javari (largest Indigenous territories in Brazil that border Peru) (De Almeida Matos, 2003).

Matsés communities are located along the Javari River basin of the Amazon, which forms a boundary between Brazil and Peru; hence the term river people. This term, which was previously used by Jesuits to refer to inhabitants of that area, is not formally a word in the Matsés language.[2] The language is vigorous and is spoken by all age groups in the Matsés communities. In the Matsés communities several other Indigenous languages are also spoken by women who have been captured from neighboring tribes and some mixture of the languages occur.[3][4] Dialects are Peruvian Matsés, Brazilian Matsés, and the extinct Paud Usunkid.

Number of Speakers and Level of Endangerment

[edit]From research gathered in 2003, Fleck states that the Matsés language is spoken by approximately 2000-2200 Amerindians, since being contacted back in 1969.[5] In Brazil, the Matsés inhabit the Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory (IT) that covers 8,519,800 hectares of land. The land is distributed into eight communities that are mostly located within the IT borders. According to a more recent census (2007), the population of Matsés in Brazil was 1,143 people. Meanwhile, in 1998, the Peruvian Matsés population reached a total of 1,314 people.

It is very common for Matsés families in the northern Pano group to shift between villages including villages across national borders. As a result, it becomes difficult to establish trustworthy data for the Matsés populations in Brazil and Peru. Currently, Matsés in Brazil identify themselves as monolingual, since most children in Matsés communities are nurtured and taught exclusively in the Indigenous language. For this reason, the level of endangerment of this language is relatively low. The Instituto Socioambiental states: "Only those people who have worked or studied in the surrounding Peruvian or Brazilian towns speak Portuguese or Spanish fluently." This strongly indicates that the language will sustain itself throughout generations. One of the most important functions of language is to produce a social reality that is reflective of that language's culture. When children are raised learning the language, the continuation of the cultural traditions, values, and beliefs is enabled, reducing the chances of that language becoming endangered.[6]

History of the People

[edit]Contact with Indigenous and Non-Indigenous People

[edit]The origin of the Matsés population is directly related to the merger of various Indigenous communities that did not always speak mutually intelligible languages. Historically, the Matsés participated in looting and planned raids on other Pano groups. The incentive for these attacks involved the massacre of that particular Pano group's Indigenous men, so that their women and children became powerless due to lack of protection. The Matsés, consequently, would inflict their superiority and dominance by killing off warrior men of the other Indigenous’ groups so that the women and children of the other groups would have no other choice but to join the Matsés, where they would have to learn to assimilate to their new family and lifestyle. From approximately the 1870s to about the 1920s, the Matsés lost their access to the Javari River due to the boom of the rubber industry which was centered in the Amazon basin, where the extraction and commercialization of rubber threatened the Matsés lifestyle.[6] During this period, the Matsés avoided conflict with non-Indigenous people and relocated to interfluvial areas, while maintaining a pattern of dispersal that allowed them to avoid the rubber extraction fronts. Direct contact between the Matsés and non-Indigenous people commenced around the 1920s. In a 1926 interview between Romanoff and a Peruvian man working on the Gálvez river, the Peruvian declared that rubber bosses were unable to set up on the Choba river due to Indigenous attacks. These attacks ignited a response from the non-Indigenous people, who kidnapped Matsés woman and children. This resulted in intensified warfare, and successful Matsés attacks meant that they were able to recover their people, along with firearms and metal tools. Meanwhile, warfare between the Matsés and other Indigenous groups continued. By the 1950s, the wave of rubber tappers fizzled and was later replaced by "logging activity and the trade in forest game and skins, mainly to supply the towns of Peruvian Amazonia."[6]

Health

[edit]Presently, the Matsés have failed to receive adequate health care for over a decade. Consequently, diseases such as "malaria, worms, tuberculosis, malnutrition and hepatitis"[6] have continued without reduction. The lack of organization and distribution of appropriate vaccinations, medication and prevention methods has resulted in high levels of deaths among the Matsés. The main problem is that most Indigenous communities lack medications and/or medical tools – microscopes, needles, thermometers – that help make basic diagnoses of infections and diseases. For instance, Matsés today suffer "high levels of hepatitis B and D infections" and hepatic complications such as hepatitis D can cause death in just a matter of days. It is unfortunate that the organization responsible for health care in the IT fails to live up to their responsibilities and as a result the Indigenous population is negatively impacted. It also causes the Matsés communities to distrust the use of vaccines. These people now fear falling ill, and do not receive clear information as to what caused the symptoms of their deceased kin. Sadly, "The Matsés do not know how many of them are infected, but the constant loss of young people, most of them under 30 years old, generates a pervasive mood of sadness and fear."[6]

Education

[edit]In Brazil, Matsés communities are considered to be monolingual, so teachers are recruited from the community itself. Teachers tend to be elders; individuals that the community trusts to teach the youth although they have never completed formal teacher training. Attempts have been made to promote Indigenous teacher training. The state education secretary for the Amazons has been formally running a training course, but lack of organization means that the classes are offered only sporadically (De Almeida Matos, 2003). Presently, only two Matsés schools exist in the "Flores and Três José villages" constructed by the Atalaia do Norte municipal council. Despite complaints from the Matsés communities, funding and construction of official Matsés schools is rare. As a consequence, Matsés parents, who hope to provide their family with higher education and greater job opportunities, send their children to neighbouring towns for their education. The lack of Matsés schools -- that would have focused on Indigenous knowledge, culture, and language -- consequently raises the likelihood of children assimilating into a culture unlike their own, decreasing the chances of cultural transmission to the next generation of Matsés children.

Language Family

[edit]Currently, the Matsés language belongs to one of the largest subsets within the Northern Pano region. Panoan is a family of languages known to be spoken in Peru, western Brazil, and Bolivia. In turn, Panoan languages are included within the larger Pano-Tacanan family. This language group includes languages of Indigenous groups similar to the Matsés, including Matis, Kulina-Pano, Maya, Korubo, and other groups that presently evade contact with the outside world (De Almeida Matos, 2003). Not only are these Indigenous groups culturally similar, they share mutually intelligible languages. Compared to the other groups in the northern Pano subset, the Matsés have the largest population.

Literature Review

[edit]Bibliographies about Panoan and Matsés/Mayoruna linguistic and anthropological sources can be found in Fabre (1998),[7] Erikson (2000),[8] and Erikson et el. (1994).[9] A Pano-Takana bibliography written by Chavarría Mendoza in 1983 is outdated but still has relevant and interesting information about some linguistic and anthropological works on the Matsés.[10] Missionaries from the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), including Harriet Kneeland and Harriet L. Fields, produced the first descriptions of the Matsés language. Researchers utilized escaped captives as consultants and were able to study the language and culture from the verbal affirmations of captives before they were able to make contact in 1969.

The most extensive published grammatical description of this language is the educational work done by the SIL, intended to teach the Matsés language to Spanish speakers. This work focused on the morphology of the language as well as the phonology and syntax systems. Literature which includes phonological descriptions, grammatical descriptions, collections of texts and word lists can be found in the work published by Fields and Kneeland during (approximately) 1966 to 1981. Kneeland (1979) has developed an extensive modern lexicon for Matsés which includes approximately an 800-word Matsés-Spanish glossary, along with some sample sentences. Work completed by Wise (1973) contains a Spanish-Matsés word list with approximately 150 entries.[11]

Carmen Teresa Dorigo de Carvalho, a Brazilian fieldworker and linguist, has been conducting linguistic analyses based on her work about the Brazilian Matsés. Her contributions to the study of this language include her Master's thesis on Matsés sentence structure and a PhD dissertation on Matsés phonology, based on an optimality theory treatment of Matsés syllable structure and many other aspects of Matsés phonology.[11] In addition to this work, she published an article about Matsés tense and aspect, an article on split ergativity, and an unpublished paper on negation in Matsés and Marubo.

Organizations that Promote Indigenous Rights and Documentation Projects

[edit]The non-governmental organization, Indigenous Word Center (CTI) was founded in March 1979 by anthropologists and indigenists who had already done prior work with some Indigenous people in Brazil. This organization has a mark of its identity with the Indigenous people that way they can effectively contribute to having control of their territories, clarifying the role of the State and protecting and guaranteeing their constitutional rights. This organization operates on the Indigenous Lands located in the Amazon, Cerrado and Atlantic Forest Biomes (Centro de Trabalgo Indigenista, 2011). The general coordinator of this organization is Gilberto Azanha and the program coordinator is Maria Elisa Ladeira. The Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA) that was founded on April 22, 1994, is an organization of Civil Society of Public Interest by people with training and experience in the fight for environmental and social rights. The objective of this organization is to defend social, collective and diffuse goods and rights that have to do with cultural heritage, the environment, or humans right. The ISA is in charge of research and various studies, they implement projects and programs that promote social and environmental sustainability as well as valuing cultural and biological diversity of the country. The board of directors of this organization include Neide Esterci, Marina Kahn, Ana Valéria Araújo, Anthony Gross, and Jurandir Craveiro Jr (Centro de Trabalgo Indigenista, 2011).

Other Materials

[edit]Comprehensive descriptions of the general Matsés culture can be found in Romanoff's 1984 dissertation; discussion of the Mayoruna subgroups history and culture can be found in Erikson's 1994 dissertation; and information about Matsés contemporary culture and history can be found in Matlock's 2002 dissertation.[12] The first anthropologist to work among the Matsés was Steven Romanoff, who published an article on Matsés land use, a short article on Matsés women as hunters, as well as his Ph.D. dissertation. Works by Erikson (1990a, 1992a, and 2001) are all useful published ethnographic studies about the Matis in Brazil, which are relevant to the description of the Mayoruna subgroup, but lacking specific data on the Matsés. Luis Calixto Méndez, a Peruvian anthropologist, has also been working with the Matsés for several years. At first he did some ethnographic research among the Matsés, but in recent years his research has been restricted to administrative work for the Non-Government Organization Centre for Amazonian Indigenous Development.[13]

Phonology

[edit]Matsés has 21 distinctive segments: 15 consonants and 6 vowels. Along with these vowels and consonants, contrastive stress also is a part of the phoneme inventory. The following charts contain the consonants and vowels of the language, as well as their major allophones that are indicated in parentheses.

Vowels

[edit]The vowel system of Matsés is peculiar in that no vowels are rounded. Both of its back vowels should accurately be represented as [ɯ] and [ɤ] but the convention is to transcribe them orthographically with ⟨u⟩ and ⟨o⟩.[14]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɨ | ɯ |

| Mid | ɛ | ɤ | |

| Open | ɑ |

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ŋ) | |||

| Plosive | p b | t d | k | (ʔ) | ||

| Fricative | s | ʂ | ʃ | |||

| Affricates | ts | tʂ | tʃ | |||

| Approximant | w | j | ||||

| Flap | ɾ |

Morphology

[edit]The Indigenous Brazilian language, Matsés is a language that falls into the classification of both an isolating and a polysynthetic language. Typically, single-morpheme words are common, and some longer words could include to about 10 morphemes. Still, the general use of morphemes per word in the language have the tendency to involve 3 to 4.[16] Half of the Matsés language makes use of simple morphemes, while "verbal inflectional suffixes, transitivity agreement enclitics, and class-changing suffixes are, with very few exceptions, portmanteau morphemes."[16] Morphemes normally, imply a one-to-one association between the two domains, but the Matsés language permits portmanteau morphemes to be part of the morphology. The distinction applies to morphemes, as productive synchronically segmented forms, while a formative morpheme includes "historical forms that are fossilized sub-morphemic elements with form-meaning associations."[17] Interestingly, root words in the language, possess lexical meaning and needs to occupy the nuclear parts of the word. What helps identify the nuclear word, is when it involves the use of free morphemes within the phrase, also if it occurs alone without other phonologically attached material.[17] Free and bound morphemes also distinguish roots from affixes/clitics. Roots are morphemes that can also occur with inflectional morphology. With that being said, some adverbs must be inflected for a transitivity agreement as well as verbs that are not being used in the imperative mode, or that occur alone as monomorphemic words. Reason being, semantically monomorphemic words are incompatible with the imperative mode.[17] All roots in the language can occur with no phonologically attached material, or with inflectional morphology. A stem is combined with either a root with one, none, or multiple affixes/clitics.[18] While, words are defined as a stem that is combined with inflectional suffixes, when it is necessary to do so.

A pronoun is a word used as a substitute for a noun, it may function alone or as a noun phrase to refer either to the participants in the discourse or to something mentioned in the discourse. Typically, in Matsés, pronouns are divided into four types: personal, interrogative, indefinite, and demonstrative.[19] Each of these types of pronouns include three case-specific forms, that are known as absolutive, ergative/instrumental and genitive. Pronouns in this language are not distinguished by number, gender, social status or personal relations between the participants in the discourse.[19]

Inflection vs Derivation

[edit]Inflection is the change in the form of a word, usually by adding a suffix to the ending, which would mark distinctions such as tense, number, gender, mood, person, voice and case. Whereas, derivation is a formation of a new word or injectable stem that comes from another word or stem. This usually occurs by adding an affix to the word, which would make the new word have a different word class from the original. In Matsés, inflection normally only occurs on verbs as a lexical-class-wide and syntactic-position-wide phenomenon. There are a set of suffixes that include finite inflection and class-changing suffixes that must occur on finite verbs. Adjectives are also a word class that have a lexical-class-wide inflection. Adverbs and postpositions have a marginal inflectional category known as transitivity agreement.

Traditionally, derivational morphology includes meaning-changing, valence-changing and class-changing morphology. In the reading A Grammar of Matsés by David Fleck, he uses the term "derivational" to refer to only meaning-changing and valence-changing morphology. This is due to the fact that class-changing morphology patterns are closely related to inflectional suffixes. For the verbs in Matsés, the inflectional suffixes and class-changing suffixes are in pragmatic contrast, (shown in example 1), so it could be concluded that all verbs in this language either require class-changing morphology or inflection.[21]

opa

dog

cuen-me-boed

run.off-CAUS-REC.PST:NMLZ

nid-ac

go-INFR

‘The one who made the dog run off has left’[22]

opa

dog

cuen-me-ash

run.off-CAUS-after:S/A>S

nid-o-sh

go-Past-3

adverbialization

‘After making the dogs run off, he left’[22]

Table 2 displays the differences between derivational and inflectional/class-changing morphology in the language Matsés.[22]

| Derivational Morphology | Inflectional/Class-changing morphology |

|---|---|

|

|

Reduplication

[edit]There was a generalization put forth by Payne (1990) stating that in lowland South American languages, all cases of reduplication is iconic.[23] This means that it is indicating imperfective action, greater intensity, progressive aspect, iterative, plurality, or onomatopoeia of repeated sounds. But, the language Matsés, does not confirm this generalization. In Matsés there are various different meanings that have to do with reduplication, which includes iconic, non-iconic, and "counter-iconic" reduplication. A summary of the different functions and meanings of reduplication in Matsés are shown in Table 3.[24]

| Iconic |

|

|---|---|

| Non-iconic |

|

| "Counter-iconic" |

|

Syntax

[edit]Case and Agreement

[edit]The Indigenous Brazilian language known as Matsés, is considered to be an ergative-absolutive system. Sentences in this language case mark the subject of an intransitive sentence equal to the object of a transitive sentence. In particular, the subject of a transitive sentence is treated as the ergative, while the subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a transitive verb is weighed as the absolutive.[25] To identify core arguments based on noun phrases, absolutive argument are identified via noun or noun phrase that are not the final part of a larger phrase and occur without an overt marker.[26] Non-absolutive nominals are marked in one of the three following ways i) case-marking ii) phonologically independent, directly following postposition word or iii) occurs as a distinct form, that generally incorporates a nasal.[26] In contrast, ergative arguments are identifiable through ergative nouns or noun phrases’ that are "case-marked with the enclitic -n, identical to instrumental and genitive case markers, and to the locative/temporal postpositional enclitic."[27] Pronoun forms are easier distinctive, in form and/or distribution.[28] There are four pronominal forms associated with the four -n enclitics and this suggests that there are four independent markers in contrast to a single morpheme with a broader range of functions. Enclitics suggest that the four markers could be either: ergative, genitive, instrumental and locative, where each enclitic represent different kinds of morphemes.[29] The locative noun phrase can be replaced by deictic adverbs where as an ergative, genitive, and instrumental are replaced by pronouns in the language. The locative postpositional enclitic -n is the core argument marker, and additionally is phonologically identified to the ergative case marker. This means, that it can code two different semantic roles, locative and temporal.[30] Ergative and absolutive are imposed by predicates and are later identified as cases, since they are lexically specified by the verbs, and never occur optionally. Adjacently, genitive cases are not governed by predicates but rather the structure of the possessive noun phrase. Since, most possessive noun phrases require the possessor to be marked as a genitive, some postposition require their objects to be in the genitive case if human.[30] Together with, coding ownership, interpersonal relation, or a part-whole relation, the genitive marker obtains the syntactic function of marking the genitive noun as subordinate to a head noun.[31] Finally, instrumental is that least prototypical case however, like the ergative, instrumental is allowed per clause. Unlike the ergative, it occurs optionally. Instrumental cases also require remote causative constructions of inanimate causes to appear and if there is an overt agent in a passive clause, than by definition it is an instrumental case.[32]

Semantics

[edit]Plurals

[edit]In Matsés, the suffix -bo may be optionally attached to a noun that refers to humans, but excluding pronouns. This is used to specify that the referent involves a homogeneous category, shown in example 1, but it could also occur with a non-human reference to show a heterogeneous category, although this is quite rare (example 2 and 3).[33]

Abitedi-mbo

all-AUG

uënës-bud-ne-ac

die-DUR-DISTR-Narr.PAST

mëdin-bo

deceased.person-PL

aid

that.one

‘All of them have died off, the now deceased one… those ones.’

chompian-bo

shotgun-PL

‘Different types of shotguns’/ ‘shotguns, etc.’

poshto-bo

woolly.monkey-PL

‘Woolly monkeys and other types of monkeys’

Padnuen

By.contrast

sinnad

palm.genus

utsi-bo

other-PL

mannan-n-quio

hill-LOC-AUG

cani-quid

grow-HAB

'By contrast, other kinds of sinnad palms grow deep in the hills [upland forest].'

With human subjects, the plurality indicator -bo is used to either indicate a set of people in a group (4a), a category of people (4a, and 5), or with numerous people who are acting separately (4a, and 6). In addition to the suffix –bo indicating plurality, the verbal suffixes –cueded or –beded are used to specify collective semantics, used either with or without –bo (4b).[33]

chido-bo

woman-PL

choe-e-c

come-NPAST-IND

‘A group of women are coming’

‘Women (always) come.’

‘Women are coming (one by one)’

chido(-bo)

women(-PL)

cho-cueded-e-c

come-Coll:S/A-NPAST-IND

‘A group of women are coming’

tsësio-bo-n-uid-quio

old.man-PL-ERG-only-AUG

sedudie

nine.banded.armadillo

pe-quid

eat-HAB

‘Only old men eat nine-banded armadillos’

cun

1Gen

papa

father

pado-bo-n

deceased-PL-ERG

cain-e-c

wait-NPAST-IND

‘My late father and my uncles wait for them [historical present]’

Usually a Matsés speaker would leave out the -bo suffix and let the speaker figure out the plurality from the context, or if number is important in the context, the speaker would use a quantitative adverb such as daëd ‘two’, tëma ‘few’, dadpen ‘many’.[33]

Another plurality indicator in this language is the suffix -ado. This suffix is used to specify that all members are being included and it can even include members that are in similar categories, whereas the suffix -bo only refers to a subset of a kinship category. This difference is shows in example 7a and 7b.[34]

cun

1Gen

chibi-bo

younger.sister-PL

‘My younger sisters’

‘My younger female parallel cousins’

cun

1Gen

chibi-ado

younger.sister-PL:Cat.Ex

‘My younger sisters and younger female parallel cousins (and others sisters, and female cousins)’

Pisabo "language"

[edit]| Pisabo | |

|---|---|

| Mayo | |

| Native to | Peru, Brazil |

Native speakers | 600 (2006)[35] |

(unattested) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | pig |

| Glottolog | pisa1244 |

| ELP | Matsés |

Pisabo, also known as Pisagua (Pisahua), is a purported Panoan language spoken by approximately 600 people in Peru and formerly in Brazil, where it was known as Mayo (Maya, Maia) and was evidently the language known as Quixito.[36] However, no linguistic data is available,[37] and it is reported to be mutually intelligible with Matses.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Matsés at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Fleck 2003, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Fields & Wise 1976, p. 1.

- ^ Fleck 2006, p. 542.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. ii.

- ^ a b c d e De Almeida Matos 2003.

- ^ Fabre, Alain (1998). Manual de las Lenguas Indigenas Sudamericanas II. München: Lincom Europa.

- ^ Erikson, Philippe (2000). "Bibliografía anotada de Fuentes con interés para la etnología y etnohistoria de los Pano setentrionales (Matses, Matis, Korubo...)". Amazonia Peruana. 27: 231–287.

- ^ Erikson, Philippe; Illius, Bruno; Kensinger, Kenneth; Sueli de Aguilar, María (1994). "Kirinkobaon kirika ("Gringo's Books). An annotated Panoan bibliography". Amerindia. 19, Supplement 1.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 41.

- ^ a b Fleck 2003, p. 43.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 46.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 47.

- ^ a b Fleck 2003, p. 72.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 72).

- ^ a b Fleck 2003, p. 204.

- ^ a b c Fleck 2003, p. 206.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 207.

- ^ a b Fleck 2003, p. 240.

- ^ a b Fleck 2003, p. 244.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d Fleck 2003, p. 213.

- ^ Payne 1990, p. 218.

- ^ a b Fleck 2003, p. 220.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 828.

- ^ a b Fleck 2003, p. 824.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 825.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 826.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 827.

- ^ a b Fleck 2003, p. 829.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 830.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 831.

- ^ a b c Fleck 2003, p. 273.

- ^ Fleck 2003, p. 275.

- ^ Matsés language at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Campbell & Grondona 2012, p. 102.

- ^ Fleck 2013.

References

[edit]- Saúde na Terra Indígena Vale do Javari: Diagnóstico médico-antropológico: subsídios e recomendações para uma política de assistência (PDF) (Report). Centro de Trabalho Indigenista. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-06.

- Campbell, Lyle; Grondona, Veronica, eds. (2012). The Indigenous Languages of South America: A Comprehensive Guide. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-3-11-025513-3.

- De Almeida Matos, Beatriz. "Matsés". Povos Indígenas no Brasil. Instituto Socioambiental.

- Fleck, David William (2003). A grammar of Matses (PhD thesis). Rice University. hdl:1911/18526.

- Fleck, David W. (2013). "Panoan languages and linguistics". Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. American Museum of Natural History Anthropological Papers. 99. American Museum of Natural History: 1–112. doi:10.5531/sp.anth.0099. hdl:2246/6448. ISSN 0065-9452.

- Kneeland, Harriet (1982). "El 'ser como' y el 'no ser como' de la comparación en matsés". In Wise, Mary Ruth; Boonstra, Harry (eds.). Conjunciones y otros nexos en tres idiomas amazónicos. Serie Lingüística Peruana. Vol. 19. Lima: Ministerio de Educación and Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. pp. 77–126. OCLC 9663970.

- Kneeland, Harriet (1973). "La frase nominal relativa en mayoruna y su ambigüedad". In Loos, Eugene E. (ed.). Estudios panos 2. Serie Lingüística Peruana. Vol. 11. Yarinacocha: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. pp. 53–105.