Pillbox (military)

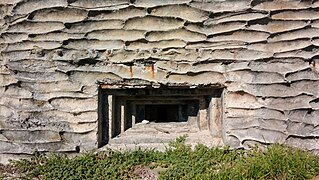

A pillbox is a type of blockhouse, or concrete dug-in guard-post, often camouflaged, normally equipped with loopholes through which defenders can fire weapons. It is in effect a trench firing step, hardened to protect against small-arms fire and grenades, and raised to improve the field of fire.

The modern concrete pillbox originated on the Western Front of World War I, in the German Army[1] in 1916.

Etymology

[edit]

The origin of the term is disputed. It has been widely assumed to be a jocular reference to the perceived similarity of the fortifications to the cylindrical and hexagonal boxes in which medical pills were once sold; also, the first German concrete pillboxes discovered by the Allies in Belgium were so small and light that they were easily tilted or turned upside down by the nearby explosion of even medium (240mm) shells.[3] However, it seems more likely that it originally alluded to pillar boxes, with a comparison being drawn between the loophole on the pillbox and the letter-slot on the pillar box.[4]

The term is found in print in The Times on 2 August 1917, following the beginning of the Third Battle of Ypres; and in The Scotsman on 17 September 1917, following the German withdrawal onto the Hindenburg Line. Other unpublished occurrences have been found in war diaries and similar documents of about the same date; and in one instance, as "Pillar Box", as early as March 1916.[4]

Characteristics

[edit]The concrete nature of pillboxes means that they are a feature of prepared positions. Some pillboxes were designed to be prefabricated and transported to their location for assembly. During World War I, Sir Ernest William Moir produced a design for concrete machine-gun pillboxes[5] constructed from a system of interlocking precast concrete blocks, with a steel roof. Around 1,500 Moir pillboxes were eventually produced (with blocks cast at Richborough in Kent) and sent to the Western Front in 1918.[6][7]

Pillboxes are often camouflaged to conceal their location and to maximise the element of surprise. They may be part of a trench system, form an interlocking line of defence with other pillboxes by providing covering fire to each other (defence in depth), or they may be placed to guard strategic structures such as bridges and jetties.

Pillboxes are hard to defeat and require artillery, anti-tank weapons or grenades to overcome.

Uses

[edit]The French Maginot Line built between the world wars consisted of a massive bunker and tunnel complex, but as most of it was below ground, little could be seen from the ground level. The exception were the concrete blockhouses, gun turrets, pillboxes and cupolas which were placed above ground to allow the garrison of the Maginot line to engage an attacking enemy.[8]

Between the Abyssinian Crisis of 1936 and World War II, the British built about 200 pillboxes on the island of Malta for defence in case of an Italian invasion.[9] Fewer than 100 pillboxes still exist, and most are found on the northeastern part of the island. A few of them have been restored and are cared for, but many others were demolished. Some pillboxes are still being destroyed nowadays as the authorities do not consider them to have any architectural or historic value,[10] despite heritage NGOs calling to preserve them.[11]

About 28,000 pillboxes and other hardened field fortifications were constructed in Britain in 1940 as part of the British anti-invasion preparations of World War II. About 6,500 of these structures still survive.[12]

Pillboxes for the Czechoslovak border fortifications were built before World War II in Czechoslovakia in defence against a German attack. None of these were actually used against their intended enemy during the German invasion, but some were used against the advancing Soviet armies in 1945. The Japanese also made use of pillboxes in their fortifications of Iwo Jima, and on other occupied islands and territories.

About 750,000 pillboxes (Albanian: bunkerët) were built by the Albanian Hoxhaist government from the 1960s until the 1980s in Cold War paranoia, most never used for their intended purpose although few were used in the Insurrection of 1997 and the 1999 Kosovo War and the construction costs were a scandalous drain on needed funds for social development.[13][14][15] Most are now derelict, though some have been repurposed as residential accommodations, cafés, nightclubs, storehouses, cabins, animal shelters and one in Tirana as a museum.[16][17][18][19]

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, pillboxes have been used to gain advantages in trench warfare.[20]

Gallery

[edit]-

A pillbox in Balaklava, Crimea.

-

Pillbox at Putney Bridge in London, England

-

A type 10 pillbox on the Siegfried Line in Aachen, Germany

-

A square pillbox in St Julian's, Malta

-

A camouflaged pillbox in Qrendi, Malta

-

An Israeli pillbox 5.4 metres above ground, Modi'in-Maccabim-Re'ut (near Route 443)

-

A guard pillbox used on Robben Island during World War II

-

Exterior of a quay pillbox in Ikata, Japan

-

Interior of a quay pillbox in Ikata, Japan

-

Blockhouse south of Le Touquet, France. It was part of the Atlantic Wall

Notes

[edit]- ^

Pegler, Martin (20 August 2014). Soldiers' Songs and Slang of the Great War. Bloomsbury Publishing (published 2014). ISBN 9781472809292. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

pill-box [:] A concrete fortification mostly used for machine guns, invented by the Germans.

- ^ "Photos show Second War War pillbox on beach which has collapsed". www.edp24.co.uk. 18 February 2021.

- ^ Hellis, John. "Why the name Pillbox?" Pillbox Study Group

- ^ a b Oldham 2018

- ^ "Papers on:- Machine-gun pill-box designed by Mr. E. W. Moir, Munitions Council member". National Archives of the UK. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Oldham 2011

- ^ "Moir pillbox". South East History Boards. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Schneider & Kitchen 2002, p. 87.

- ^ "Guided tour of WWII defences". Times of Malta. 2 December 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Wartime pillbox at Salina being pulled down". The Malta Independent. 10 April 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Leone Ganado, Philip (30 August 2016). "WWII pillbox is not worth preserving, cultural watchdog says". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016.

- ^ CBA staff.

- ^ Obscura, Atlas (27 September 2013). "Albania's 750,000 Concrete Cold War Bunkers". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ "Bunkers of Albania". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ Galjaard, David (2012). Concresco. Slavenka Drakulić, Jaap Scholten. [Netherlands?]. ISBN 978-94-6190-781-3. OCLC 841773976.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wheeler, Tony (2007). Tony Wheeler's Bad Lands. Lonely Planet. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-74179-186-0.

- ^ Barger, Jennifer; Bellingreri, Marta (24 March 2021). "Once a state secret, these Albanian bunkers are now museums". National Geographic. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Allan (13 June 2019). "The Cold War Bunkers of Albania". The Atlantic. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Former nuclear bunker becomes museum of Albanian persecution". Chicago Sun-Times. 20 November 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ Hernandez, Marco; Holder, Josh (14 December 2022). "Defenses Carved Into the Earth". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

References

[edit]- CBA staff, A Review Of The Defence of Britain Project, Council for British Archaeology, retrieved 30 May 2006[dead link]

- Hellis, John (1 June 2001). "Why the name Pillbox?". Pillbox Study Group. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- Hibbs, Peter (20 April 2016). "About the Defence of East Sussex Project". www.pillbox.org.uk. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- "pillbox, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Oldham, Peter (2011). Pill Boxes on the Western Front: A Guide to the Design, Construction and Use of Concrete Pill Boxes, 1914–1918. Pen & Sword. ISBN 9781473817227.

- Oldham, Peter (2018). "'Pill box', 'pillbox' or 'pill-box'? What's in a name?". Stand To! The Journal of the Western Front Association. 112: 15–21.

- Schneider, Richard Harold; Kitchen, Ted (2002), Planning for crime prevention: a transatlantic perspective, RTPI library series, vol. 3 (illustrated ed.), Routledge, p. 87, ISBN 978-0-415-24136-6 – via books.google.com

External links

[edit] Media related to Pillboxes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pillboxes at Wikimedia Commons