Piano Sonata No. 31 (Beethoven)

| Piano Sonata | |

|---|---|

| No. 31 | |

| by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

Beethoven in 1820 | |

| Key | A♭ major |

| Opus | 110 |

| Composed | 1821 |

| Published | 1822 |

| Movements | 3 |

The Piano Sonata No. 31 in A♭ major, Op. 110, by Ludwig van Beethoven was composed in 1821 and published in 1822. It is the middle piano sonata in the group of three (Opp. 109, 110, and 111) that he wrote between 1820 and 1822, and is the penultimate of his piano sonatas. Though the sonata was commissioned in 1820, Beethoven did not begin work on Op. 110 until the latter half of 1821, and final revisions were completed in early 1822. The delay was due to factors such as Beethoven's work on the Missa solemnis and his deteriorating health. The original edition was published by Schlesinger in Paris and Berlin in 1822 without dedication, and an English edition was published by Muzio Clementi in 1823.

The work is in three movements. The Moderato first movement follows a typical sonata form with an expressive and cantabile opening theme. The Allegro second movement begins with a terse but humorous scherzo, which Martin Cooper believes is based on two folk songs, followed by a trio section. The last movement comprises multiple contrasting sections: a slow introductory recitative, an arioso dolente, a fugue, a return of the arioso, and a second fugue that builds to a passionate and heroic conclusion. William Kinderman finds parallels between the last movement's fugue and other late works by Beethoven, such as the fughetta in the Diabelli Variations and sections of the Missa solemnis, and Adolf Bernhard Marx favourably compares the fugue to those of Bach and Handel. The sonata is the subject of musical analyses including studies by Donald Tovey, Denis Matthews, Heinrich Schenker, and Charles Rosen. It has been recorded by pianists such as Artur Schnabel, Glenn Gould, and Alfred Brendel.

Background

[edit]In the summer of 1819, Adolf Martin Schlesinger, from the Schlesinger firm of music publishers based in Berlin, sent his son Maurice to meet Beethoven to form business relations with the composer.[1] The two met in Mödling, where Maurice left a favourable impression on the composer.[2] After some negotiation by letter, the elder Schlesinger offered to purchase three piano sonatas for 90 ducats in April 1820, though Beethoven had originally asked for 120 ducats. In May 1820, Beethoven agreed, and he undertook to deliver the sonatas within three months. These three sonatas are the ones now known as Opp. 109, 110, and 111, the last of Beethoven's piano sonatas.[3]

The composer was prevented from completing the promised sonatas on schedule by several factors, including his work on the Missa solemnis (Op. 123),[4] rheumatic attacks in the winter of 1820, and a bout of jaundice in the summer of 1821.[5][6] Barry Cooper notes that Op. 110 "did not begin to take shape" until the latter half of 1821.[7] Although Op. 109 was published by Schlesinger in November 1821, correspondence shows that Op. 110 was still not ready by the middle of December 1821. The sonata's completed autograph score bears the date 25 December 1821, but Beethoven continued to revise the last movement and did not finish until early 1822.[8] The copyist's score was presumably delivered to Schlesinger around this time, since Beethoven received a payment of 30 ducats for the sonata in January 1822.[9][10]

Adolf Schlesinger's letters to Beethoven in July 1822 confirm that the sonata, along with Op. 111, was being engraved in Paris. The sonata was published simultaneously in Paris and Berlin that year, and it was announced in the Bibliographie de la France on 14 September. Some copies of the first edition reached Vienna as early as August, and the sonata was announced in the Wiener Zeitung that month.[8] The sonata was published without a dedication,[11] though there is evidence that Beethoven intended to dedicate Opp. 110 and 111 to Antonie Brentano.[12] In February 1823, Beethoven sent a letter to the composer Ferdinand Ries in London, informing him that he had sent manuscripts of Opp. 110 and 111 so that Ries could arrange their publication in Britain. Beethoven noted that while Op. 110 was already available in London, the edition had mistakes that would be corrected in Ries's edition.[13] Ries persuaded Muzio Clementi to acquire the British rights to the two sonatas,[14] and Clementi published them in London that year.[15]

Form

[edit]The sonata is in three movements, though Schlesinger's original edition separated the third movement into an Adagio and a Fuga.[10] Alfred Brendel characterises the main themes of the sonata as all derived from the hexachord – the first six notes of the diatonic scale – and the intervals of the third and fourth that divide it. He also points out that contrary motion is a feature in much of the work, and is particularly prominent in the second movement.[16]

The main themes of each movement begin with a phrase covering the range of a sixth. Another point of significance is the note F, which is the sixth degree of the A♭ major scale. F forms the peak of the first phrase of the sonata and acts as the tonic of the second movement. Fs in the right hand also begin the second movement's trio section and the third movement's introduction.[17]

The sonata lasts 19 minutes.[18]

I. Moderato cantabile molto espressivo

[edit]

The first movement in A♭ major is marked Moderato cantabile molto espressivo ("at a moderate speed, in a singing style, very expressively").[19] Denis Matthews describes the first movement as "orderly and predictable sonata form",[20] and Charles Rosen calls the movement's structure Haydnesque.[21] Its opening is marked con amabilità (amiably).[22] After a pause on the dominant seventh, the opening is extended in a cantabile theme. This leads to a light arpeggiated demisemiquaver transition passage. The second group of themes in the dominant E♭ includes appoggiatura figures, and a bass which descends in steps from E♭ to G three times while the melody rises by a sixth. The exposition ends with a semiquaver cadential theme.[23]

The development section (which Rosen calls "radically simple"[21]) consists of restatements of the movement's initial theme in a falling sequence, with underlying semiquaver figures. Donald Tovey compares the artful simplicity of the development with the entasis of the Parthenon's columns.[24]

The recapitulation begins conventionally with a restatement of the opening theme in the tonic (A♭ major), Beethoven combining it with the arpeggiated transition motif. The cantabile theme gradually modulates via the subdominant to E major (a seemingly remote key which both Matthews[25] and Tovey[26] rationalise by viewing it as a notational convenience for F♭ major). The harmony soon modulates back to the home key of A♭ major. The movement's coda closes with a cadence over a tonic pedal.[27]

II. Allegro molto

[edit]

The scherzo is marked Allegro molto (very fast). Matthews describes it as "terse",[25] and William Kinderman as "humorous",[28] even though it is in the F minor key. The rhythm is complex with many syncopations and ambiguities. Tovey observes that this ambiguity is deliberate: attempts to characterise the movement as a gavotte are prevented by the short length of the bars implying twice as many accented beats – and had he wanted to, Beethoven could have composed a gavotte.[29]

Beethoven uses antiphonal dynamics (four bars of piano contrasted against four bars of forte), and opens the movement with a six-note falling-scale motif. Martin Cooper finds that Beethoven indulged the rougher side of his humour in the scherzo by using motifs from two folk songs, "Unsa kätz häd kaz'ln g'habt" ("Our cat has had kittens") and "Ich bin lüderlich, du bist lüderlich" ("I am a draggle-tail, you are a draggle-tail").[30] Tovey earlier decided that such theories of the themes' origins were "unscrupulous", since the first of these folk songs was arranged by Beethoven some time before this work's composition in payment for a publisher's trifling postage charge – the nature of the arrangement making it clear that the folk songs were of little importance to the composer.[31]

The trio in D♭ major juxtaposes "abrupt leaps" and "perilous descents",[25] ending quietly and leading to a modified reprise of the scherzo with repeats, the first repeat written out to allow for an extra ritardando. After a few syncopated chords the movement's short coda comes to rest in F major (a Picardy third) via a long broken arpeggio in the bass.[32]

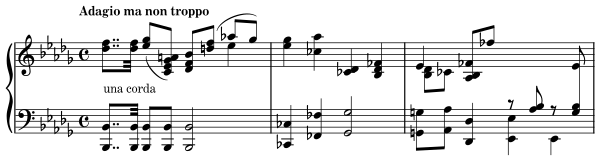

III. Adagio ma non troppo – Allegro ma non troppo

[edit]

The third movement's structure alternates two slow arioso sections with two faster fugues. In Brendel's analysis, there are six sections – recitative, arioso, first fugue, arioso, fugue inversion, homophonic conclusion.[33] In contrast, Martin Cooper describes the structure as a "double movement" (an Adagio and a finale).[34]

The scherzo's concluding ritardando F major bass arpeggio resolves to B♭ minor in the third movement's beginning,[28] indicating a departure from the humour of the scherzo.[35] Following three bars of introduction is the unbarred recitative,[36] during which the tempo changes multiple times.[35] This then leads to an A♭ minor arioso dolente, a lament whose initial melodic contour is similar to the opening of the scherzo (although Tovey dismisses this as insignificant).[37] The arioso is marked "Klagender Gesang" (Song of Lamentation) and is supported by repeated chords.[38] Commentators (including Kinderman and Rosen) have seen the initial recitative and arioso as "operatic",[28][35] and Brendel writes that the lament resembles the aria "Es ist vollbracht" (It is finished) from Bach's St John Passion.[39] The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians notes that the term "arioso" is rarely used in instrumental music.[40]

The arioso leads into a three-voice fugue in A♭ major, whose subject is constructed from three parallel rising fourths separated by two falling thirds ().[37] The opening theme of the first movement carries within it elements of this fugue subject (the motif A♭–D♭–B♭–E♭),[36][41] and Matthews sees a foreshadowing of it in the alto part of the first movement's antepenultimate bar.[25] The countersubject moves by smaller intervals.[36] Kinderman finds a parallel between this fugue and the fughetta of the composer's later Diabelli Variations (Op. 120), and also notes similarities with the "Agnus Dei" and "Dona nobis pacem" sections of the contemporaneous Missa solemnis.[28] Gould contrasts this fugue, which is used in a "lyric, idyllic, contemplative" context, with the violent but disciplined fugue from the Hammerklavier sonata (Op. 106) that "revealed the turbulent, forceful Beethoven".[42]

The fugue is broken off by a dominant seventh of A♭ major, which resolves enharmonically onto a G minor chord in second inversion.[43][44] This leads into a reprise of the arioso dolente in G minor marked ermattet (exhausted).[45] Kinderman contrasts the perceived "earthly pain" of the lament with the "consolation and inward strength" of the fugue[43] – which Tovey points out had not reached a conclusion.[44] Rosen finds that G minor, the tonality of the leading note, gives the arioso a flattened quality befitting exhaustion,[46] and Tovey describes the broken rhythm of this second arioso as being "through sobs".[47]

The arioso ends with repeated G major chords of increasing strength,[43] repeating the sudden minor-to-major device that concluded the scherzo.[28] A second fugue emerges with the subject of the first inverted, marked wieder auflebend (again reviving; poi a poi di nuovo vivente – little by little with renewed vigour – in the traditional Italian);[45][48] Brendel ascribes an illusory quality to this passage.[39] Some performance instructions in this passage begin poi a poi and nach und nach (little by little).[48] Initially, the pianist is instructed to play una corda (that is to use the soft pedal). The final fugue gradually increases in intensity and volume,[48] initially in the key of G major.[43] After all three voices have entered, the bass introduces a diminution of the first fugue's subject (whose accent is also altered), while the treble augments the same subject with the rhythm across the bars. The bass eventually enters with the augmented version of the fugue subject in C minor, and this ends on E♭. During this statement of the subject in the bass, the pianist is instructed to gradually raise the una corda pedal.[49] Beethoven then relaxes the tempo (marked Meno allegro)[50] and introduces a truncated double-diminution of the fugue subject; after statements of the first fugue subject and its inversion surrounded by what Tovey calls the "flame" motif, the contrapuntal parts lose their identity.[51] Brendel views the section that follows as a "[shaking] off" of the constraints of polyphony;[39] Tovey labels it a "peroration", calling the passage "exultant".[52] It leads to a closing four-bar tonic arpeggio and a final emphatic chord of A♭ major.[53]

Matthews writes that it is not fanciful to see the final movement's second fugue as a "gathering of confidence after illness or despair",[45] a theme which can be discerned in other late works by Beethoven (Brendel compares it with the Cavatina from the String Quartet No. 13).[39] Martin Cooper describes the coda as "passionate" and "heroic", but not out of place after the ariosos' distress or the fugues' "luminous verities".[54] Rosen states that this movement is the first time in the history of music where the academic devices of counterpoint and fugue are integral to a composition's drama, and observes that Beethoven in this work does not "simply symbolize or represent the return to life, but persuades us physically of the process".[48]

Reception

[edit]From the 1810s Beethoven's reputation went largely undisputed by contemporary critics, and most of his works received favourable initial reviews.[55] For example, an anonymous reviewer in October 1822 described the Op. 110 sonata as "superb" and offered "repeated thanks to its creator".[56] In 1824, an anonymous critic reviewing the Opp. 109–111 sonatas wrote in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung that contemporary opposition against Beethoven's works "had only small, fleeting success". The critic then commented, "Scarcely had any of [Beethoven]'s artistic productions entered into the world than their fame was forever established."[55]

Adolf Bernhard Marx, in his March 1824 review of the sonata, lauded Beethoven's work and particularly praised the third movement's fugue, adding that the fugue "must be studied along with the richest ones by Sebastian Bach and Händel."[57] In the 1860 edition of his biography of Beethoven, Anton Schindler wrote that the fugue "is not difficult to play but is full of charm and beauty."[58] Likewise, William Kinderman describes the fugue's subject as a "sublime fugal idiom".[28]

When writing about the sonata in 1909, Hermann Wetzel observed, "Not a single note is superfluous, and there is no passage ... that can be treated as you please, no trivial ornament". Martin Cooper claimed in 1970 that Op. 110 was the most frequently played out of the last five Beethoven piano sonatas.[59]

In the program notes for his 2020 online concert of the Opp. 109–111 sonatas, Jonathan Biss writes of Op. 110: "In none of the other 31 piano sonatas does Beethoven cover as much emotional territory: it goes from the absolute depths of despair to utter euphoria ... it is unbelievably compact given its emotional richness, and its philosophical opening idea acts as the work’s thesis statement, permeating the work, and reaching its apotheosis in its final moments."[18]

Recordings

[edit]The first known recording of the Op. 110 sonata was made on 14 December 1927 and 8 March 1928 by Frederic Lamond. The Op. 110 sonata was recorded on 21 January 1932 by Artur Schnabel in Abbey Road Studios, London, for the first complete recording of the Beethoven piano sonatas. The piece was the first to be recorded in the set.[60] Myra Hess' recording of the work in 1953[61] was described by The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians as among her "greatest successes in the recording studio".[62] Op. 110 was included in Glenn Gould's 1956 recording of the last three Beethoven sonatas,[63] and its third movement was discussed and performed by Gould on a 4 March 1963 broadcast.[42] As part of complete recordings of the Beethoven piano sonatas, Op. 110 was recorded by Wilhelm Kempff in 1951,[64] Claudio Arrau in 1965,[65] Alfred Brendel in 1973,[66] Maurizio Pollini in 1975,[67] Daniel Barenboim in 1984,[68] and Igor Levit in 2019.[69]

References

[edit]- ^ Sonneck 1927, p. 301.

- ^ Thayer 1970, p. 734.

- ^ Thayer 1970, p. 762.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Thayer 1970, pp. 776–777.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 305.

- ^ a b Tyson 1963, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Tyson 1977, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Cooper 2008, p. 308.

- ^ Cooper 1970, p. 196.

- ^ Thayer 1970, p. 781.

- ^ Thayer 1970, p. 861.

- ^ Sonneck 1927, p. 307.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 311.

- ^ Brendel 1991, p. 69.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 309.

- ^ a b Biss 2020.

- ^ Tovey 1976, p. 271.

- ^ Matthews 1986, p. 52.

- ^ a b Rosen 2002, p. 236.

- ^ Rosen 2002, p. 235.

- ^ Tovey 1976, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Tovey 1976, p. 272.

- ^ a b c d Matthews 1986, p. 53.

- ^ Tovey 1976, p. 273.

- ^ Tovey 1976, pp. 273–274.

- ^ a b c d e f Kinderman 2013, p. 81.

- ^ Tovey 1976, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Cooper 1970, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Tovey 1976, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Tovey 1976, p. 277.

- ^ Brendel 1991, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Cooper 1970, p. 191.

- ^ a b c Rosen 2002, p. 238.

- ^ a b c Tovey 1976, p. 281.

- ^ a b Tovey 1976, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Cooper 1970, p. 192.

- ^ a b c d Brendel 1991, p. 70.

- ^ Budden et al. 2001.

- ^ Kinderman 2013, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Gould 2018.

- ^ a b c d Kinderman 2013, p. 82.

- ^ a b Tovey 1976, p. 283.

- ^ a b c Matthews 1986, p. 54.

- ^ Rosen 2002, p. 239.

- ^ Tovey 1976, p. 284.

- ^ a b c d Rosen 2002, p. 240.

- ^ Tovey 1976, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Rosen 2002, p. 241.

- ^ Tovey 1976, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Tovey 1976, pp. 286–287.

- ^ Tovey 1976, p. 287.

- ^ Cooper 1970, p. 195.

- ^ a b Wallace 2001, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Wallace 2020, p. 55.

- ^ Wallace 2020, pp. 56–59.

- ^ Schindler 1972, p. 214.

- ^ Cooper 1970, p. 187.

- ^ Bloesch 1986, p. 80.

- ^ Hess 2013.

- ^ Morrison 2001.

- ^ Gould 1956.

- ^ Kempff 1995.

- ^ Arrau 1998.

- ^ Brendel 2011.

- ^ Pollini 2014.

- ^ Barenboim 1999.

- ^ Levit 2019.

Sources

[edit]Book sources

[edit]- Brendel, Alfred (1991). Music Sounded Out. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-37452-331-2.

- Cooper, Barry (2008). Beethoven. The Master Musicians. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531331-4.

- Cooper, Martin (1970). Beethoven, The Last Decade 1817–1827. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315310-6.

- Kinderman, William (2013). "Beethoven". In R. Larry Todd (ed.). Nineteenth-Century Piano Music. New York: Routledge. pp. 55–96. ISBN 978-1-13673-128-0.

- Matthews, Denis (1986). Beethoven Piano Sonatas. London: BBC Publications. ISBN 0-563-20510-5.

- Rosen, Charles (2002). Beethoven's Piano Sonatas, A Short Companion. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09070-6.

- Schindler, Anton (1972) [1860]. MacArdle, Donald W. (ed.). Beethoven as I Knew Him. Translated by Jolly, Constance S. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-00638-7.

- Thayer, Alexander Wheelock (1970). Forbes, Elliot (ed.). Thayer's Life of Beethoven. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02702-1.

- Tovey, Donald Francis (1976) [1931]. A Companion to Beethoven's Pianoforte Sonatas (revised ed.). New York: AMS Press. ISBN 0-40413-117-4.

- Tyson, Alan (1977). Beethoven Studies 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315315-7.

- Wallace, Robin (2001). "Beethoven's Critics: An Appreciation". In Senner, Wayne M. (ed.). The Critical Reception of Beethoven's Compositions by His German Contemporaries. Translated by Wallace, Robin. Lincoln & London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1251-8.

- Wallace, Robin, ed. (2020). The Critical Reception of Beethoven's Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 101 to Op. 111 (PDF). Translated by Wallace, Robin. Boston: Center for Beethoven Research, Boston University. ISBN 978-1-73489-4820.

Other sources

[edit]- Biss, Jonathan (2020). "Notes on the Program" (PDF). Program notes for "Jonathan Biss, piano". 92Y. 26 March 2020.

- Bloesch, David (1986). "Artur Schnabel: A Discography" (PDF). Association for Recorded Sound Collections Journal. 18 (1–3): 33–143.

- Budden, Julian; Carter, Tim; McClymonds, Marita P.; Murata, Margaret; Westrup, Jack (2001). "Arioso". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.01240. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Gould, Glenn (6 April 2018) [4 March 1963]. Glenn Gould – Beethoven, Piano Sonata No. 31 in A-flat major op. 110 (video). The Glenn Gould Estate. Event occurs at 0:50 to 2:10. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021.

- Morrison, Bryce (2001). "Hess, Dame Myra". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.12935. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Sonneck, Oscar G. (1927). "Beethoven to Diabelli: A Letter and a Protest". The Musical Quarterly. 13 (2). Oxford University Press: 294–316. doi:10.1093/mq/XIII.2.294. JSTOR 738414.

- Tyson, Alan (1963). "Maurice Schlesinger as a Publisher of Beethoven, 1822–1827". Acta Musicologica. 35 (4). International Musicological Society: 182–191. doi:10.2307/932536. JSTOR 932536.

Recordings

[edit]- Arrau, Claudio (1998). Beethoven - The Complete Piano Sonatas & Concertos (Recording). Philips Classics Records – via Presto Music.

- Barenboim, Daniel (1999). Beethoven – Complete Piano Sonatas (Recording). Deutsche Grammophon – via Presto Music.

- Brendel, Alfred (2011). Alfred Brendel: Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas & Concertos (Recording). Decca Records – via Presto Music.

- Gould, Glenn (1956). Beethoven, L.: Piano Sonatas Nos. 30–32 (Gould) (1956) (Recording). Naxos Records.

- Hess, Myra (2013). Myra Hess: Complete Solo & Concerto Studio Recordings (Recording). Appian Publications & Recordings. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021 – via Presto Music.

- Kempff, Wilhelm (1995). Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1–32 (Recording). Deutsche Grammophon – via Presto Music.

- Levit, Igor (2019). Beethoven: Complete Piano Sonatas (Recording). Sony Classical Records – via Presto Music.

- Pollini, Maurizio (2014). Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1–32 (Recording). Deutsche Grammophon – via Presto Music.

Further reading

[edit]- Greenberg, Robert (2005). Beethoven's Piano Sonatas. Chantilly: The Teaching Company. ISBN 978-1-59803-0143.

- Schenker, Heinrich (2015). Rothgeb, John (ed.). Piano Sonata in A♭ Major Op. 110: Beethoven's Last Piano Sonatas, An Edition with Elucidation. Translated by Rothgeb, John. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199914227.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-991422-7.

External links

[edit]- A lecture by András Schiff on the Op. 110 sonata

- 1930 recording by Artur Schnabel of the Op. 110 sonata

- Piano Sonata No. 31, Op. 110 at AllMusic

- Piano Sonata No. 31, Op. 110: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project