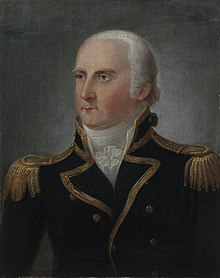

Philip Gidley King

Philip Gidley King | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd Governor of New South Wales | |

| In office 28 September 1800 – August 1806 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | John Hunter |

| Succeeded by | William Bligh |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 23 April 1758 Launceston, Cornwall, England, Great Britain |

| Died | 3 September 1808 (aged 50) London, England, United Kingdom |

| Resting place | St Nicholas churchyard, Lower Tooting, London |

| Spouse | Anna Josepha Coombe |

| Children | 3 sons (incl. Phillip), 4 daughters |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Branch/service | Royal Navy |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | Australian Frontier Wars |

Captain Philip Gidley King (23 April 1758 – 3 September 1808) was a Royal Navy officer and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New South Wales from 1800 to 1806. When the First Fleet arrived in January 1788, King was detailed to colonise Norfolk Island for defence and foraging purposes. As Governor of New South Wales, he helped develop livestock farming, whaling and mining, built many schools and launched the colony's first newspaper. But conflicts with the military wore down his spirit, and they were able to force his resignation. King Street in the Sydney CBD is named in his honour.

Early years and establishment of Norfolk Island settlement

[edit]Philip Gidley King was born at Launceston, England on 23 April 1758, the son of draper Philip King, and grandson of Exeter attorney-at-law John Gidley.[1] He joined the Royal Navy at the age of 12 as captain's servant, and was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1778. King served under Arthur Phillip who chose him as second lieutenant on HMS Sirius for the expedition to establish a convict settlement in New South Wales. On arrival, in January 1788, King was selected to lead a small party of convicts and guards to set up a settlement at Norfolk Island, leaving Sydney on 14 February 1788 on board HMS Sirius.[2][3][4]

On 6 March 1788, King and his party landed with difficulty, owing to the lack of a suitable harbour, and set about building huts, clearing the land, planting crops, and resisting the ravages of grubs, salt air and hurricanes. More convicts were sent, and these proved occasionally troublesome. Early in 1789 he prevented a mutiny when some of the convicts planned to take him and other officers prisoner, and escape on the next boat to arrive. Whilst commandant on Norfolk Island, King formed a relationship with the female convict Ann Inett—their first son, born on 8 January 1789, was named Norfolk. (He went on to become the first Australian-born officer in the Royal Navy and the captain of the schooner Ballahoo.) Another son was born in 1790 and named Sydney.[3][4][5]

Following the wreck of Sirius at Norfolk Island in March 1790, King left and returned to England to report on the difficulties of the settlements at New South Wales. Ann Inett was left in Sydney with the boys; she later married another man in 1792, and went on to lead a comfortable and respected life in the colony. King, who had probably arranged the marriage, also arranged for their two sons to be educated in England, where they became officers in the navy. Whilst in England King married Anna Josepha Coombe (his first cousin) on 11 March 1791 and returned shortly after on HMS Gorgon to take up his post as Lieutenant-Governor of Norfolk Island, at an annual salary of £250. King's first legitimate offspring, Phillip Parker King, was born there in December 1791, and four daughters followed.[3][4]

On his return to Norfolk Island, King found the population of nearly one thousand torn apart by discontent after the strict regime of Major Robert Ross. However, he set about enthusiastically to improve conditions. He encouraged settlers, drawn from ex-convicts and ex-marines, and he listened to their views on wages and prices. By 1794 the island was self-sufficient in grain, and surplus swine were being sent to Sydney. The number of people living off the government store was high, and few settlers wanted to leave. In February 1794 King was faced with unfounded allegations by members of the New South Wales Corps on the island that he was punishing them too severely and ex-convicts too lightly when disputes arose. As their conduct became mutinous, he sent twenty of them to Sydney for trial by court-martial. There Lieutenant-Governor Francis Grose censured King's actions and issued orders which gave the military illegal authority over the civilian population. Grose later apologised, but conflict with the military continued to plague King.[3][4]

Governor of New South Wales

[edit]Suffering from gout, King returned to England in October 1796, and after regaining his health, and resuming his naval career, he was appointed to replace Captain John Hunter as the third Governor of New South Wales. King became governor on 28 September 1800. He set about changing the system of administration, and appointed Major Joseph Foveaux as Lieutenant-Governor of Norfolk Island. His first task was to attack the misconduct of officers of the New South Wales Corps in their illicit trading in liquor, notably rum. He tried to discourage the importation of liquor, and began to construct a brewery. However, he found the refusal of convicts to work in their own time for other forms of payment, and the continued illicit local distillation, increasingly difficult to control. He continued to face military arrogance and disobedience from the New South Wales Corps. He failed to receive support in England when he sent an accused officer John Macarthur back to face a court-martial.[3][4]

King had some successes. His regulations for prices, wages, hours of work, financial deals and the employment of convicts brought some relief to smallholders, and reduced the numbers 'on the stores'. He encouraged construction of barracks, wharves, bridges, houses, etc. Government flocks and herds greatly increased, and he encouraged experiments with vines, tobacco, cotton, hemp and indigo. Whaling and sealing became important sources of oil and skins, and coal mining began. He took an interest in education, establishing schools to teach convict boys to become skilled tradesmen. He encouraged smallpox vaccinations, was sympathetic to missionaries, strove to keep peace with the indigenous inhabitants, ordered the printing of Australia's first book, New South Wales General Standing Orders, and encouraged the first newspaper, the Sydney Gazette.[6] Exploration led to the survey of Bass Strait and Western Port, and the discovery of Port Phillip, and settlements were established at Hobart and Port Dalrymple in Van Diemen's Land.[3][4]

While still aware that Sydney was a convict colony and always alert to the ebb and flow of the rebellious Irish political prisoners he established his own body guard. He gave opportunities to emancipists, considering that ex-convicts should not remain in disgrace forever. He appointed emancipists to positions of responsibility, regulated the position of assigned servants, and laid the foundation of the 'ticket of leave' system for deserving prisoners. For a period he allowed toleration of Catholics, permitting Fr James Dixon to say mass for Irish convicts.[7][8] Although he directly profited from a number of commercial deals, cattle sales, and land grants, he was modest in his dealings compared with most of his subordinates. Most famously he quelled the Castle Hill Rebellion in March 1804. The increased animosity between King and the New South Wales Corps led to his resignation and replacement by William Bligh in 1806, and he returned to England. Here his health failed and he died on 3 September 1808.[3][4]

Although he worked hard for the good of New South Wales and left it very much better than he found it, the abuse from the officers harmed his reputation, and illness and the hard conditions of his service eventually wore him down. Of all the members of the First Fleet, Philip Gidley King perhaps made the greatest contribution to the early years of the colony.[3]

Artist

[edit]King is also remembered for his art works, several of which survive. An engraving by William Blake, entitled A Native Family of New South Wales, and published in John Hunter's Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island (1793) was made from one of his watercolors. The original sketch is among the Banks Papers held by the Mitchell Library, Sydney, along with several others, unsigned but clearly by the same artist.[9]

Recognition

[edit]King Street is a street in Sydney’s central business district. It starts at King Street Wharf on Darling Harbour in the west and goes to Queens Square in the East.

King Street was named after Governor Phillip Gidley King.

The top end of King Street has been home to the legal profession since Governor Macquaie established the Supreme Court next to St James’ Church. King Street was also closely positioned to newspaper buildings and to pubs, clubs and theatres.[10] According to “Australian Bird Names: A Complete Guide” by Jeannie Gray & Ian Fraser,[11] the name King’s Parrot was proposed by George Caley to honour Governor Philip Gidley King (Governor of New South Wales from 1800-1806).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Phillip 1970, p. 50

- ^ "Old Families of New South Wales". The Sunday Times. Sydney, NSW: National Library of Australia. 9 December 1923. p. 13. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shaw, A. G. L. (1967). "King, Philip Gidley (1758–1808)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Serle, Percival (1949). "King, Philip Gidley". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ^ Gillen, Mollie (1989). The Founders of Australia: a biographical dictionary of the First Fleet. Sydney: Library of Australian History. p. 608. ISBN 0-908120-69-9.

- ^ "Establishing Law and Order – NSW General Standing Orders". State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Proclamation, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 24 April 1803

- ^ Franklin, James (2021). "Sydney 1803: When Catholics were tolerated and Freemasons banned" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 107 (2): 135–155. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Gleeson, James (1971). Colonial Painters 1788–1880. Lansdowne Press for Australian Art Library. ISBN 0701809809.

- ^ "Archives & History Resources". King Street Sydney. City of sydney. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Fraser, Ian; Gray, Jeannie (September 2019). AUSTRALIAN BIRD NAMES Cover of Australian Bird Names 2nd Edn featuring a line illustration of a powerful owl peering out from the cover with one eye Enlarge cover Origins and Meanings. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9781486311644.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cheesman, Evelyn (1950). Landfall the Unknown: Lord Howe Island 1788. Penguin Books.

- Phillip, Arthur (1970). Auchmuty, J. J. (ed.). The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, with an Account of the Establishment of the Colonies of Port Jackson and Norfolk Island. Angus and Robertson. ISBN 0207953104.

- Richards, D. Manning (2012). Destiny in Sydney: An epic novel of convicts, Aborigines, and Chinese embroiled in the birth of Sydney, Australia. First book in Sydney series. Washington DC: Aries Books. ISBN 978-0-9845410-0-3

External links

[edit]- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Works by Philip Gidley King at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Philip Gidley King at the Internet Archive

- Governors of New South Wales

- Royal Navy captains

- People from Launceston, Cornwall

- 1758 births

- 1808 deaths

- Australian penal colony administrators

- Norfolk Island penal colony administrators

- 19th-century Australian politicians

- Australian people of Cornish descent

- British emigrants to Australia

- Colony of New South Wales people

- Sea captains

- First Fleet