Petko Karavelov

Petko Karavelov Петко Стойчев Каравелов | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th Prime Minister of Bulgaria | |

| In office 10 December 1880 – 9 May 1881 | |

| Monarch | Alexander |

| Preceded by | Dragan Tsankov |

| Succeeded by | Johann Casimir Ernrot |

| In office 11 July 1884 – 21 August 1886 | |

| Monarch | Alexander |

| Preceded by | Dragan Tsankov |

| Succeeded by | Kliment Turnovski |

| In office 24 August 1886 – 28 August 1886 | |

| Monarch | Alexander |

| Preceded by | Kliment Turnovski |

| Succeeded by | Vasil Radoslavov |

| In office 5 March 1901 – 4 January 1902 | |

| Monarch | Ferdinand |

| Preceded by | Racho Petrov |

| Succeeded by | Stoyan Danev |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 7 April 1880 – 9 May 1881 | |

| Premier | Dragan Tsankov (7 April 1880 - 10 December 1880) Himself (10 December 1880 - 9 May 1881) |

| Preceded by | Grigor Nachovich |

| Succeeded by | Georgi Zhelyazkovich |

| In office 11 July 1884 – 21 August 1886 | |

| Premier | Himself |

| Preceded by | Mikhail Sarafov |

| Succeeded by | Todor Burmov |

| In office 4 March 1901 – 3 January 1902 | |

| Premier | Himself |

| Preceded by | Khristo Bonchev |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Sarafov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Petko Stoichev Karavelov 24 March 1843 Koprivshtitsa, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 24 January 1903 (aged 59) Sofia, Bulgaria |

| Resting place | Sveti Sedmochislenitsi Church, Sofia |

| Nationality | Bulgarian |

| Political party | Liberal Party (1878–1886) Democratic Party (1886–1903) |

| Spouse | Ekaterina Karavelova |

| Children | Lora Karavelova (daughter) |

| Relatives | Lyuben Karavelov (brother) |

| Alma mater | Imperial Moscow University (1866) |

| Occupation | Teacher |

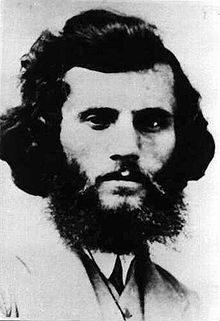

Petko Stoychev Karavelov[1] (Bulgarian: Петко Стойчев Каравелов; 24 March 1843 – 24 January 1903) was a leading Bulgarian liberal politician who served as prime minister on four occasions.

Early years

[edit]Born in Koprivshtitsa,[2] his older brother Lyuben initially became more well known as a writer and leading member of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee.[2] Initially educated at the Greek language school at Enez, Karavelov was an apprentice weaver until he left for Moscow at the age of 16.[2] There he studied history and philology at Moscow State University before serving as a tutor to a number of prominent families.[2] He also served in the Russian Army during the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878.[citation needed] In 1878, the Russians appointed him the deputy governor of Svishtov,[citation needed] before he was elected to the new Assembly for the Liberal Party.[3]

Prime minister

[edit]Karavelov was first offered the premiership in 1879 when Prince Alexander asked him to head up a coalition administration. Karavelov rejected the offer however, as Alexander required an anti-Russian government that would curb freedoms, both tenets being unacceptable to the Liberals.[4] He first served as Prime Minister from 1880–1881 but was effectively declared persona non grata when Alexander suspended the constitution in 1881.[5] A number of Liberals followed Karavelov into exile although a sizeable group remained in Bulgaria, creating a division in the party.[6] He relocated to Plovdiv, in the semi-autonomous Eastern Rumelia, where he found work as a teacher, before returning to Bulgaria proper in 1884.[5] He also served as a Mayor of Plovdiv during his exile.

Karavelov then returned as Prime Minister from 1884 to 1886, overseeing Bulgarian unification and the Serbo-Bulgarian War.[5] It is claimed that in 1885 Karavelov was involved in a Russian-led plot to oust Alexander along with his wife Ekaterina, although it is unknown if the Russian envoys convinced the Karavelovs to become fully involved in the scheme.[7] He joined Stefan Stambolov and others as a member of the Regency Council after the abdication of Alexander of Bulgaria in 1886, serving a brief third spell as Prime Minister in August of that year.[5] His reigns as Prime Minister where characterized by close association with Russia. Karavelov was criticised as a poor public speaker who let his ego determine many of his political decisions, although supporters lauded him as a pragmatist and a statesman with a keen academic mind.[2]

Out of favour

[edit]As a committed liberal, he became associated with the Democratic Party after the party split. He broke from his former ally Stambolov and was imprisoned 1891-1894, after being accused of instigating the assassination of government Minister Hristo Belchev. During this and other shorter prison spells under Stambolov Karavelov was subjected to torture.[5] He was amnestied in 1894 with the resignation of Stambolov.[8]

Later years

[edit]Karavelov was a founder of the Democratic Party around the turn of the century.[1] In contrast to Karavelov's earlier opinions, the new group favoured a free hand in foreign policy but preferred a closer relationship with the western European powers rather than Russia.[9] By this point he was recognised as the "grand old man" of democratic liberalism in Bulgaria and was the centre of a wide circle of influential followers in the nation's capital Sofia.[10] He briefly returned in 1901 to lead the party's first government.

Karavelov is buried alongside his wife in the grounds of the Sveti Sedmochislenitsi Church, Sofia with their grave being the only one in the church (which has no cemetery).[11] He was father of Lora Karavelova, who was married to Peyo Yavorov. She committed suicide in 1913 during an argument with her husband which led to Yavorov being tried for, and acquitted of, her murder.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Frederick B. Chary, The History of Bulgaria, ABC-CLIO, 2011, p. 181

- ^ a b c d e Duncan M. Perry, Stefan Stambolov and the Emergence of Modern Bulgaria: 1870-1895, Duke University Press, 1993, p. 246

- ^ Charles Jelavich & Barbara Jelavich, Establishment of the Balkan National States: 1804-1918, University of Washington Press, 1977, p. 160

- ^ Perry, Stefan Stambolov and the Emergence of Modern Bulgaria, p. 50

- ^ a b c d e Francisca De Haan, Krasimira Daskalova, Anna Loutfi, Biographical Dictionary of Women's Movements and Feminisms: Central, Eastern, and South Eastern Europe, 19th and 20th Centuries, Central European University Press, 2006, p. 231

- ^ R. J. Crampton, A Concise History of Bulgaria, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 93

- ^ Perry, Stefan Stambolov and the Emergence of Modern Bulgaria, p. 70

- ^ Leon Trotsky, The Balkan wars: 1912-13 : the war correspondence of Leon Trotsky, Resistance Books, 1980, p. 475

- ^ Jelavich & Jelavich, Establishment of the Balkan National States, p. 193

- ^ Rochelle Goldberg Ruthchild, Equality & Revolution: Women's Rights in the Russian Empire, 1905-1917, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010, p. 37

- ^ De Haan et al, Biographical Dictionary of Women's Movements and Feminisms, p. 234

- ^ Jonathan Bousfield, Dan Richardson, Richard Watkins, Rough Guide to Bulgaria 4, Rough Guides, 2002, p. 93

Further reading

[edit]- Black, Cyril E. (1943). The Establishment of Constitutional Government in Bulgaria. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 71, 77–78, 79, 83, 85–86, 86–87, 94, 123, 129, 157, 164, 165, 167, 181, 186, 190, 194, 206, 218, 224–228, 244–245, 249, 254, 257–258, 261–264. Retrieved January 7, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- 1843 births

- 1903 deaths

- Chairpersons of the National Assembly of Bulgaria

- People from Koprivshtitsa

- Liberal Party (Bulgaria) politicians

- Democratic Party (Bulgaria) politicians

- Regents of Bulgaria

- Prime ministers of Bulgaria

- Finance ministers of Bulgaria

- Mayors of Plovdiv

- Members of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

- Members of the National Assembly (Bulgaria)

- Russian military personnel of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

- People of the Serbo-Bulgarian War

- Moscow State University alumni

- 19th-century Bulgarian people

- Imperial Moscow University alumni

- Justice ministers of Bulgaria