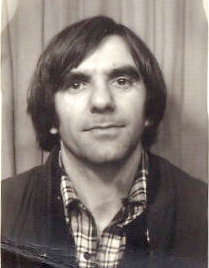

Peter-Paul Zahl

Peter-Paul Zahl (March 14, 1944, in Freiburg im Breisgau – January 24, 2011, in Port Antonio, Jamaica) was a German-born anarchist–libertarian writer and director. He last held dual German–Jamaican citizenship.

His extensive work, which includes lyric poetry, prose, and plays, is marked by the politicization of literature in West German society as a result of the 1968 movement. He was honored in 1980 for the picaresque novel Die Glücklichen and in 1995 for the crime novel Der schöne Mann.

In the late 1960s, he became known in West Berlin as the printer of the underground magazine Agit 883 and as a publisher and author of subcultural writings from the radical leftist social environment, which brought him into the focus of law enforcement.

After critically wounding a police officer in a shootout while fleeing from police, he was imprisoned from 1972 to 1982. In 1976, the Düsseldorf District Court sentenced him to 15 years in prison for two counts of attempted murder. While in prison, Zahl intensified his literary work. He then became involved in cultural politics for the New Jewel Movement in Grenada and the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. From 1985 he lived primarily in Jamaica.

Life

[edit]Childhood and youth

[edit]

Zahl was born in Freiburg, Germany, in the penultimate year of World War II, the son of Hilde Zahl, a secretary, and Paul Zahl, a lawyer. His parents stayed there in 1944 when his father received medical treatment for a severe war injury and leg amputation. Towards the end of the war, the family moved back to their hometown of Feldberg in Mecklenburg with their one-year-old child, where the father founded the children's book publishing house Peter-Paul, named after his son, in 1947. The company was successful and soon became the second-largest children's book publisher in the GDR.[1] As a privately owned company, however, it ran counter to state economic planning, and in 1951 Paul Zahl was denied a new license to continue the business. Due to further difficulties with the state authorities, the Zahl family moved to West Germany in 1953, settling first in Wülfrath and later in Ratingen in the Rhineland.[2]

The family found it difficult to adapt to their new surroundings, as the father remained unemployed and there were problems with the payment of his war pension. About two decades later, Peter-Paul Zahl himself described the move to the West as the end of an "extremely beautiful and happy childhood.[3] He first attended high school in Velbert, then in Ratingen until he graduated from Mittlere Reife, before completing his apprenticeship as a small offset printer in Düsseldorf from 1961 to 1964, passing his journeyman's examination with a grade of "very good". During his apprenticeship, he was considered "difficult" and "critical" by his superiors. He was politically active, joining the Printing and Paper Union and the Conscientious Objection Society.[4]

West Berlin 1964—1972

[edit]In 1964 Zahl moved his primary residence to West Berlin to avoid conscription, which was not implemented due to the Allied reservation of rights for citizens in the western sectors of the city. He worked as a printer and attended night school and lectures at the Free University of Berlin to become a writer. But he soon turned his back on institutional education: "They don't teach you how to write anyway. On the contrary, they just mess up your style and your class consciousness.[5] In 1965 he married his girlfriend Urte Wienen, also from his former hometown of Ratingen. The couple had two children, Raoul-Kostja,[6] born on July 16, 1969, and Nadezhda, born in 1971.[7] After the birth of their daughter, Zahl moved into a shared apartment. He was evicted from the apartment he shared with his wife because he was repeatedly not found in the marital household. The marriage ended in divorce in 1973.

In late 1965 Zahl supported an initiative by cabaret artist Wolfgang Neuss against the Vietnam War. Zahl's first publications of prose and poetry in magazines and on flyers also date from 1965. In 1966, he became a member of the Dortmunder Gruppe 61, a literary group initiated by Max von der Grün, whose aim was to create a link between writers and industrial workers. His first novel, From Someone Who Set Out to Earn Money, was published in 1970 by Karl Rauch Publishing House in Düsseldorf and received some public attention.[8]

In 1965/66 he came into contact with the student movement, from which the then extra-parliamentary opposition (APO) developed. After the formation of the Grand Coalition between the CDU/CSU and the SPD under Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger in 1966/67 and the discussion about the Emergency Laws, the APO became a socially relevant opposition to the system with revolutionary aspirations. Zahl supported the principles of the movement, but refused to be associated with student-dominated organizations such as the Socialist German Students (SDS). He saw himself as part of a proletarian youth, a mixture of "young workers, Kreuzberg bohemians, German army refugees, young booksellers".[9]

With the financial support of his parents-in-law, Zahl and his wife founded the Zahl-Wienen printing and publishing house in 1967 on Urban Street in Kreuzberg. In addition to corporate stationery and advertising, the company printed various publications and posters for the subcultural left-wing political scene. The publishing house mainly published countercultural magazines, such as the second issue of pro these in 1967. Zeitschrift für Unvollkommene by the astrologer Hans Taeger, as well as council communist and anarchist texts, including Spartacus: zeitschrift für lesbare literatur (1967–1970)[10] and the magazine pp-quadrat (1968–1970).[11] The first pp-quadrat volume contained the brochure amerikanischer faschismus by Bernd Kramer, another the description of Günter Wallraff's self-experiment with mescaline. The editions were often characterized by artistically designed collages, woodcuts and lithographs.

Zahl also wrote for the literary magazine Ulcus Molle Info and the satirical newspaper Der Metzger. With the zwergschul-ergänzungshefte,[12] the publisher brought out a series between 1968 and 1970 with writings by revolutionary thinkers that were put up for discussion in the APO. The reprint of Georg Büchner's Hessian Courier from 1834, whose call "Peace to the shacks! War on the palaces!" was adopted as the slogan of the movement.

From February 1969, the printing company produced the anarchist-libertarian magazine Agit 883, which Zahl was involved in editing until 1971. This reflected the fragmentation of the APO into different factions after its peak in 1967/1968. In numerous articles, it addressed the controversial question of the transition from protest to armed resistance, which had arisen in parts of the movement after the assassination attempt on Rudi Dutschke the previous year. When larger presses were purchased for the large-format newspaper – it was printed on DIN A2 plates – the company moved to more suitable premises at Weder Street 91 in Britz. In August 1969, after the publication of issue 25, the company was raided for the first time. This was because the then Senator of the Interior, Kurt Neubauer, was depicted on the cover with the words "Wanted for kidnapping", which was considered offensive by the authorities. Further searches followed as part of a criminal investigation into Agit 883, including the anti-Vietnam War texts in issue 61 of May 1970, which the commander of the American sector in Berlin had reported to the police. Zahl was acquitted of the charges brought against him because it could not be proven that he, as the printer, knew the text.[13]

After internal disputes within the magazine's editorial staff, Zahl left Agit 883 in 1971 and founded the underground anarchist magazine Fizz, which published ten issues until 1972. The magazine advocated the creation of an urban guerrilla movement and drew on American subcultural movements such as Black power and the Weather Underground.[14] Fizz was considered the mouthpiece of the Berlin blues, especially the local group of so-called hash rebels. A large part of the violent Tupamaros West Berlin group, which was based on the concept of urban guerrilla warfare and merged with the 2 June Movement in early 1972, was recruited from this group.

As early as 1970 Zahl was involved in a small, clandestine organization called "Up against the Wall, Motherfuckers!" that specialized in forging passports for GIs stationed in Berlin who were unwilling to serve in the war to escape to Sweden.

In 1971 the authorities charged Zahl with public incitement to commit a crime and reopened the case against him. The case concerned a poster designed by future RAF member Holger Meins. It bore the title "Freedom for All Prisoners!" and had been confiscated from the print shop in May 1970. The image consisted of a sunflower stylized by a grenade and shell casings, with the names of international guerrilla and liberation movements such as the "Vietcong" in what was then South Vietnam, the Tupamaros in Uruguay, and the Black Panther Party in the U.S. inscribed on the petals.[15] Zahl was sentenced to six months' probation on April 17, 1972.[16]

Imprisonment 1972–1982

[edit]Gunfight

[edit]Later in 1972 Zahl came under suspicion of involvement in a bank robbery committed by the RAF in February of that year, but this could not be substantiated. He was put on the wanted list and declared a "wanted person". In the summer of that year, he obtained false papers and a firearm and went into hiding with friends and acquaintances.[17] On December 14, 1972, while trying to rent a car in Düsseldorf, he was confronted by two police officers. Zahl attempted to flee and the officers pursued him. An exchange of gunfire ensued, during which Zahl fatally shot one of the officers in the chest. The fugitive eventually surrendered and was apprehended with a gunshot wound to his upper arm.[18] Reconstructions of the crime, based on eyewitness testimony and recovered shell casings, indicate that Zahl fired at least three shots, and probably four and that the officers fired at least nine shots.[19] When confronted with the serious injury to the policeman after his arrest, Zahl stated that he had not intended it.[20] In an article on later efforts to reopen the case in February 1980, Der Spiegel concluded, based on the expert reconstruction of the events, that the intent to kill was doubtful and Zahl's testimony was credible.[18]

Convictions

[edit]

On May 24, 1974, Zahl was sentenced by the Düsseldorf Regional Court to four years in prison for continued resistance to authority in connection with dangerous bodily injury. The court denied intent to kill, even in the form of conditional intent, saying: "The taking of human life is not consistent with the personality". After the prosecution appealed, the 3rd Criminal Senate of the Federal Court of Justice reversed the verdict in 1975 on the grounds that the court of first instance had "misinterpreted the legal concept of conditional intent". This is the case "if the perpetrator consciously accepts that his action, which he does not want to renounce under any circumstances, can bring about the harmful result that he considers possible and not entirely remote". In addition, the Düsseldorf Regional Court had to explain "which circumstances could justify the defendant's expectations or even justifiable hopes that he would only injure his persecutors, but not kill them".[21]

In a new trial before the Düsseldorf Regional Court on March 12, 1976, Zahl was sentenced to a total of 15 years in prison for two counts of attempted murder. The court agreed with the Federal Court of Justice and found it proven that the defendant had "condoned" the killing of the two policemen. He had "undoubtedly recognized" that there was "the possibility of fatal injuries" as a result of the shots he fired, and had also "approved" of this if it occurred. The characteristics of murder under

§ 211 StGB (in German)

were to be seen in the fact that the defendant sought to conceal the crimes of forgery, unauthorized possession of weapons and dangerous bodily harm.[22]

In his closing remarks Zahl spoke of the "fascization of West German society" and the "policing of politics. After a lengthy discourse on how violence emanates from the state, he said, in response to a quote from Walter Benjamin, that where capital, the state, and bureaucracy rule, there can be no non-violent agreement. Finally, he declared that anyone "as dangerous" as he was being portrayed "must be physically destroyed if he dares to continue fighting for life and human dignity, even in prison. If not through the chimney, then at least – 15 years".[23] In the second sentence the court applied the maximum 15-year term, citing Zahl's political background and stating that the defendant was "gripped by a deep hatred of our state.[24]

The verdict sparked a public controversy, with the author himself describing it as an "11-year sentence".[19] Writing in the weekly Die Zeit on February 11, 1977, Fritz J. Raddatz asked how the chambers of the District Court could come to such different verdicts. Even though he did not call for a carte blanche for "freaks who shoot themselves free," one could not help but get the impression "that here, in addition to the condemnation of an act, an attitude is also being punished.[25] Five months later, in July 1977, the journalist Gerhard Mauz contradicted this in the news magazine Der Spiegel; Zahl had not experienced a special "terror sentence," but rather what other criminals had experienced: "He came up against the legal concept of conditional intent".[20]

The poem im namen des volkes, in which Zahl expressed his view of the condemnations in literary form, was frequently quoted in commentaries:

"on may 24, 1974

condemned me

the people

[...]

to four years

imprisonment

on march 12, 1976

sentenced

me by the people

[...]

in the same matter

to fifteen years

imprisonment

I think

that should make out

the people

among themselves

and leave me

leave me out of it."[26]

Sentence

[edit]During the first years of his sentence, Zahl was held in solitary confinement, first in Cologne-Ossendorf prison, then in Werl Prison beginning in 1977, and occasionally in Bochum prison. He considered himself a political prisoner and took part in several collective hunger strikes for better prison conditions organized by RAF prisoners who were also serving time in various prisons at the time.[27] He used his time in prison to produce an extensive literary output, which he commented on as having ensured his survival. In 1974, a novel manuscript he sent to a publisher from prison, titled Isolation, was barred from publication by a court order because its publication might jeopardize the security and order of the prison.[28] This led to public protests by the PEN Center Germany and the Association of German Writers. The text was published in 1979 under the editorship of the literary scholar Ralf Schnell in the volume Schreiben ist ein monologisches Medium. Dialoge mit und über Peter-Paul Zahl.

In February 1980, the Rudolf Alexander Schröder Foundation awarded the imprisoned writer the City of Bremen Literature Prize for his novel Die Glücklichen. He was allowed to leave prison for the award ceremony and accept the prize in person. The event was publicly discussed as a "cultural-political scandal.[29] In 1980 Zahl was transferred to Tegel Prison correction in Berlin. He was released from prison in 1981 and was able to use this status for an internship as a director at the Berlin Schaubühne in 1981/1982. During this time he also wrote a play about Georg Elser, which premiered in the 1981/1982 season at the Schauspielhaus Bochum.[30] He was able to attend the premiere on February 27, 1982, because he received prison furlough.

In December 1982, Peter Paul Zahl was released from prison after serving two-thirds of his sentence. Previously, a petition for retrial had been denied in November 1980, and a petition for clemency supported by Heinrich Böll, Ernesto Cardenal, and other prominent cultural figures had been denied in April 1981.

Central America 1983 to 2011

[edit]After his release from prison, Peter-Paul Zahl refrained from political activities in West Germany. In an interview with the Die Tageszeitung (taz) in the mid-1990s, he explained that otherwise, he would have violated the terms of his parole. He had experienced the squatter demonstrations as an incredibly exciting time, but also the militancy of the police: "I allowed Germany to actively repent, but it didn't pass the parole. [...] I can't prove myself for five years, if I go along with it, I'll end up back in prison".[31]

Instead, he accepted several invitations from abroad. He supported various neo-Marxist movements in Central America, such as the New Jewel Movement led by Maurice Bishop in the southeastern Caribbean island nation of Grenada and the SNLF in Nicaragua. Zahl accepted a request from the Grenadian Ministry of Education to establish a theater, but was expelled from the country after the U.S. invasion in 1983.[32] In 1984, he attended the Tuscany Summer University in Italy and spent time in the Seychelles.

On the recommendation of Ernesto Cardenal, Nicaragua's Minister of Culture during the 1979–1987 revolution, Zahl took over the training of actors and directors at a popular culture center in Bluefields on the Caribbean coast in 1985. He left after seven months because, he says, he had problems with the racism and machismo of the Sandinista hardliners. Despite these relatively disappointing experiences, Zahl remained committed to his preferred interpretation of the Caribbean lifestyle. In 1985, he settled in Long Bay, Portland, Jamaica.[31] In an interview, he explained that he appreciated the laziness of the country, "so if you want to do a little bit of easy going, Jamaica is the ideal country for that. The people here are anarchoid, which means they hate authority and are very anti-authoritarian and therefore very strong-willed.[33]

In 1986, he married for the second time. His wife gave birth to a daughter in December of that year. In the years that followed, Zahl and his family moved several times between Long Bay and Ratingen in the Rhineland. According to some author profiles, he has a total of nine children in five different countries, including three stepdaughters.[34] During his regular visits to Germany, Zahl worked on theater productions and undertook reading tours. He continued to publish prose and poetry, wrote plays for German theaters, and began writing crime novels in 1994.

In 1995, Peter-Paul Zahl was naturalized in Jamaica without first obtaining permission to retain his German citizenship. As a result, he automatically lost his German citizenship under German law.[35] In September 2002, the German Embassy in Kingston confiscated his passport.[36] Following an application for renaturalization, the Federal Office of Administration in Cologne issued him a certificate of naturalization on November 8, 2004; the Federal Foreign Office issued him a passport in May 2005. However, on April 19, 2006, the Administrative Court of Berlin, before which Zahl had filed a lawsuit, ruled that the loss of German citizenship did not occur in 1995 because Zahl still had a residence in Germany at that time and therefore would not have required a residence permit under the "domestic clause" in effect until 2000.[37] Zahl continued to hold Jamaican citizenship after his renaturalization.

Peter-Paul Zahl died on January 24, 2011, at the age of 66 in a Port Antonio hospital after undergoing treatment for cancer in Jamaica and Germany the previous year.[38]

Literary work

[edit]Peter-Paul Zahl's literary works include poems, essays, novels and plays, as well as social reportages, appeals, articles and pamphlets. He is best known for his state-critical poems and his novel Die Glücklichen. Ein Schelmenroman, was written in prison and published in 1979. He wrote for the Rotbuch Publishing House in Berlin. On the occasion of his 65th birthday in 2009, and even more so in numerous obituaries in 2011, the German media paid tribute to his entire oeuvre. His work was described as deeply political but undogmatic, and he was considered the bad boy of the literary scene, according to editor Gabriele Dietze, because he did not fit into any cliché.[39] His irony and, in particular, his self-irony, as well as his "very humorous relationship to his own text" are emphasized.[39] In his prose, Peter-Paul Zahl "liked to explore the abysses of good society and [set] monuments to the little lawbreakers," according to the philologist Wolfgang Harms.[40] He was not considered a political theorist or a great thinker, but a clever and talented writer and a good storyteller. Many of his publications are "shrill, aggressive, almost unbearably poster-like [...] with pointed lances," as the columnist Fritz J. Raddatz wrote in 1977, but they speak of a "disappointment disguised as laconicism, a shrug of the shoulders.[25]

Because of his biography and the contexts in which his work was created, Zahl has been compared to François Villon, Blaise Cendrars, and Miguel de Cervantes, with a clear reference to his literary activities during imprisonment and detention.[41] The search for parallels to Erich Mühsam and Ernst Toller also seems politically obvious, with particular reference to Toller's Swallow book, written in prison in 1924, to which Peter-Paul Zahl's prison poetry is not inferior.[25][42] Zahl himself often referred to Georg Büchner and Walter Benjamin in his writings, and he had a special admiration for Friedrich Hölderlin. In the mid-1970s, for example, he supported the initially controversial publication of the Frankfurt Hölderlin Edition by D. E. Sattler with an open letter in the Blättern zur Frankfurter Ausgabe No. 1:

"Why do you close your ears? Why do you block your pores? – Why do you close your eyes? Why, damn it, do you defend yourselves against tenderness and beauty and their derivatives in language [...]? Come on, sisters and brothers, you have more time than you think, read Hölderlin, listen to what he has to tell us. It is worth it."

— Peter-Paul Zahl, Le Pauvre Holterling, 1976, [43]

Zahl published mainly in underground presses, but also with renowned houses such as Rowohlt, Luchterhand, and Wagenbach. However, his "reputation as a political activist" overshadowed his literary standing, and in the end "the established literary establishment increasingly shunned him," wrote Jörg Sundermeier in the taz in 2011.[38]

Early work

[edit]Peter-Paul Zahl's first surviving publications are two so-called Spartacus flyer poems from 1966. They were designed as large-format wall posters and were used to advertise lyrical texts, here under the headings Berufsethos and The Chimney Mason. Both were included in the collection of historical documents at the German Historical Museum in Berlin.[44] In 1968 he published the story Eleven Steps to a Deed; the Polyphem publishing house, printed the book with eleven lithographs by the artist Dora Elisabeth von Steiger as a limited and numbered hand-pressed print.

Zahl's first novel, From Someone Who Set Out to Earn Money, was published in 1970 and is about a young man who cannot find work in a rural area and comes to West Berlin. In the city, he is frustrated by personal and political circumstances, moves further "east" and is sent back from there as undesirable. The first work found its way into the literary criticism of the news magazine Der Spiegel, which emphasized that the literarily neglected theme of wage labor could also be treated with new stylistic devices, contrary to the outdated concept of realism. These are not merely rhetorical; the book is designed with contextual collages of photos, drawings, and headlines. The concluding statement is: "But this piece of agitational literature overtaxes the reader..."[45]

Zahl published additional texts between 1968 and 1970, especially in the series of zwergschul-ergänzungshefte, which he edited himself. The epilogue to issue no. 4, which contained a reprint of Georg Büchner's Hessischer Landbote from 1834, is regarded as Zahl's political statement. He considered the social-revolutionary significance of Büchner's pamphlet to be as important as that of Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto, published in 1848; moreover, these "eloquent documents of German revolutionaries" were "glaringly topical" for the oppressed classes.[46]

Literary work in prison

[edit]The time in prison from 1972 to 1982 was one of Peter-Paul Zahl's most productive creative periods. He said: "I wrote an insane amount in prison. To survive better, [...] translations, essays, the novel Die Glücklichen, a huge number of complaints, poems.[41]

In addition to the novel Die Glücklichen and the play Johann Georg Elser. Ein deutsches Drama, several collections of essays and articles, as well as five volumes of poetry and two volumes of prose. The writer Michael Buselmeier describes his poetry as specific and explicit politics, an expression of the failure of the anti-authoritarian movement. He subordinates his poetry to political strategies through a closed conceptual system as a worldview. Accordingly, for Zahl, resistance is not an existential-biographical experience, but a collective resistance to which operative literature must call.[47]

"it's time

to have four eyes

back to back

it's better to fight

you have more courage"[48]

Starting in 1973, Zahl wrote Die Glücklichen, which was published in 1979 and, as the subtitle suggests, belongs to the genre of the picaresque novel. The heroes of the story live in the milieu of a Kreuzberg gangster family, the narrative perspective takes the side of a marginalized and socially underprivileged class imagined by Zahl. At the same time, however, it is a subjective depiction of the upheaval of the 1968 movement, torn between state repression and the escalation of its own political issues. Thus, the debate about an armed struggle in the underground is a central issue; the protagonists criticize the RAF and the June 2 Movement as an isolated "fighting avant-garde".[49] The "myth of the RAF" is contrasted with the subversive activities of the main characters, who work in the neighborhoods of anarchist circles that consider themselves "sub proletarian," found a party against work, and published the magazine The Happy Unemployed. This is inserted between the ninth and tenth chapters as a 25-page typescript designed by comic artist Gerhard Seyfried, just as the entire novel is interspersed with collages, newspaper clippings, and drawings, and interspersed with various stylistic forms and factual texts. The narrative also thrives on the tension between the fiction of a sensual, worldly subcultural collective and the author's detached situation in solitary confinement.[50]

In the 1980s, the novel became a cult book for an alternative left-wing scene that was influenced by the events of 1968 and "began to break away from the self-destructive actionism of the RAF.[51] The radio editor Sabine Peter described it as a "textual drug, which in all its wit also shows a decisive anger at social conditions".[52] Thirty years after its publication, Die Glücklichen was classified as a work of Culture of Remembrance; according to the literary scholar Jan Henschen, Peter-Paul Zahl had "staged a myth of origin, he had tried to make history accessible to himself and his generation.[53]

Stage works

[edit]During his last two years in prison, Zahl wrote the play Johann Georg Elser. Ein deutsches Drama. He took up the story of Georg Elser (1903–1945), a carpenter who had received little public attention until then, but who on November 8, 1939, bombed Adolf Hitler in the Munich Bürgerbräukeller and was murdered in the Dachau concentration camp shortly before the end of the war. The play was a memorial to the long-ignored resistance fighter. In addition, Zahl "took German fascism out of the exoticism of the 'completely different' and showed its frightening proximity and topicality.[54] The play was directed by Claus Peymann and Hermann Beil at the Schauspielhaus Bochum in the 1981/1982 season and premiered under the direction of Alfred Kirchner on February 27, 1982. Critics emphasized both the importance of Elser and the fact that it was brought to light by the imprisoned writer. Der Spiegel wrote: "Zahl, who once wanted to be a hero and a martyr, has portrayed a hero and a martyr in his 'Elser'. And he has succeeded – despite all the political baggage.[55]

Zahl's later stage works received neither the attention nor the respect that the Elser play had received. Mit Fritz, a German Hero oder Nr. 477 bricht aus, a play for young people, premiered at the Mannheim National Theatre on February 12, 1988, under the direction of René Geiger. It is a portrayal of the appropriation of Friedrich Schiller by politicians and Germanists of all eras.[56] Zahl wrote the 1990 comedy Die Erpresser together with the Austrian singer-songwriter Georg Danzer, who set the play to music and wrote three of the lyrics. It was torn apart by critics, here in the taz, as an "adolescent slapstick play with old political jokes, gentlemanly jokes and pompous agitprop monologues.[57] Don Juan oder der Retter der Frauen is also a comedy that Zahl created based on motifs by Tirso de Molina. It premiered on June 20, 1998, as part of the Heidenheim Folk Theatre.

Jamaican influence

[edit]In 1994, Zahl published his first crime novel, The Handsome Man, which won the Friedrich Glauser Prize a year later. In it, the author created the character of Jamaican private detective Aubrey Fraser, known as Ruffneck or Ruff, who is portrayed as a fun-loving bon vivant, modeled on Dashiell Hammett. Five more titles featuring this protagonist followed through 2005. The series has been praised by critics as "an excellent introduction to the island," providing a look at the country and its people, its history, colonial past, and social conditions.[40] In addition to the plot, it describes "the beautiful country with its people, customs and peculiarities, the taste and smell of the local cuisine," but it also denounces its dark side, the entanglements of violence, politics and corruption.[58]

In the 1999 children's book Ananzi ist schuld and the 2003 collection of short stories Anancy Mek It, Zahl drew on the character of Anancy, a spider with typical trickster attributes rooted in Jamaican mythology. Zahl has also written a cookbook on Caribbean cuisine (1998) and a travel guide to his adopted country (2002).

Zahl published a second picaresque novel, Der Domraub, in 2002. Set in Germany, it tells the story of a Belgrade-born art thief in the role of a small, likable crook who is persuaded by shady agents to rob the treasury of Cologne Cathedral. In the end, he becomes a scapegoat for other underworld thieves and state institutions who all want to put him in jail. According to literary critic Maike Albath, the novel is to be understood as a "satirical reckoning with the jurisdiction of the Federal Republic of Germany," but the author takes it too easy when he tries to create a hero who takes up arms against the system with a few old-fashioned platitudes and corny jokes.[59]

Reception

[edit]During his lifetime, the reception of his work was generally overshadowed by reflections on his person and controversies surrounding his condemnations. This polarization is still evident in the obituaries. While Die Welt Kompakt described him in January 2011 as an anarchist author and propagandist for left-wing terrorist groups,[60] the Frankfurter Rundschau on the same day referred to him as a political prisoner who had spent many years in prison because of a judicial scandal.[51]

In May 1976, the historian Golo Mann and the literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki had an argument about the relationship between the person and the work. After the announcement of the controversial second verdict against Zahl, the FAZ printed his poem mittel der obrigkeit in the Frankfurter Anthologie series founded by Reich-Ranicki:

"you have to have seen them

those faces under the Tschako

during the beatings

[...]

don't say: these pigs

say: who made them do it"[61]

The publication was accompanied by a commentary by the poet Erich Fried. In a letter dated May 26, 1976, Golo Mann asked, "How could you spoil the hitherto so successful 'Frankfurt Anthology' and publish the wretched stuff of this policeman's murderer, together with the corresponding commentary by Mr. Fried? Reich-Ranicki's answer of May 31, 1976 was: "As far as the poem by the policeman's murderer is concerned, I think the sentence comes from Wilde that the fact that someone does not pay his bill does not prove that he plays the violin badly.[62]

Dealing with the RAF

[edit]

In a 2003 article entitled Literatur und Terror, journalist and writer Enno Stahl examines the reception of the RAF in literature and notes that the "agitated atmosphere" of the 1970s means that there is still a stigma attached to dealing with the subject. One of the reasons for this is "the mythical exaggeration of the RAF's actual effectiveness and theoretical basis, in both negative and positive terms.[49] Peter-Paul Zahl's Die Glücklichen was one of the first novels to deal explicitly with this topic. As the printer of Agit 883 and co-editor of Fizz, he was familiar with the development of "radical leftist milieus, especially in Berlin. The novel traces this process and at times attempts to deal with the RAF and the June 2 movement. The author treats them with "an attitude of critical sympathy"; he does not fundamentally doubt the legitimacy of violence, but wants to see it "emanate from the people themselves:

"The question is not: legal or illegal? The question is: is this counter-violence mass, does it have a goal, is it legitimized by grassroots democracy? The insurrection, the uprising, is not the social revolution. The concept of insurrection is a concept of the political mind; the classical period of the political mind is the French Revolution, Marx, Critical Marginal Glosses, the RAF's concept of revolution is a bourgeois one."

— Peter-Paul Zahl, Die Glücklichen [63]

In doing so, Zahl is attacking the "avant-garde of the revolutionary struggle", whose actions are not morally questionable, but politically wrong. By demythologizing the RAF, however, he simultaneously constructs a new myth by placing the "lumpenproletariat" and the fun guerrillas he imagines on the good side of a black-and-white picture of society.[49]

In a 2008 study, literary scholar Sandra Beck also analyzes the question of the literary treatment of West German terrorism, taking Zahl's novel as an example of a text written under the direct impression of the German Autumn. She points to the media stylization of the author as "RAF liaison" and "head of the June 2nd Movement," which began in the 1970s and led to his works being "received from the perspective of the 'terrorist writer.[64] Beck addresses the novel's detailed descriptions of the political development of the radical left; the protagonists locate themselves in a shared past with the RAF and conduct the discussion of the legitimacy of violence in direct confrontation with quoted, "publicly banned writings. They reject terrorism because it practices the same unconditional violence as the system it opposes, "so that creativity, autonomy and the satisfaction of pleasure are replaced by brutality, discipline and dogmatism.[65] Literature opens up an aesthetic space in fictional dialogue and immediately makes it clear "that this discursive confrontation with the terrorism of the RAF is only possible in the medium of fiction.[65]

Prison literature

[edit]

In 1977, Erich Fried founded the Peter-Paul Zahl Initiative Group, which published documentation on the case and lobbied for the reopening of the trial.[66] When a planned proseminar on the imprisoned writer was banned by the administration of the Westphalian Wilhelms University in Münster in 1979, Fried spoke out against the ban at a protest event:

"Of course, incarceration alone does not turn a bad poem into an important literary work, but deprivation of liberty as such should not make a poet unsuitable for a seminar."

— Erich Fried, [67]

In a subsequent lecture on prison literature, he explained that writing produced in prisons is part of a "respectable international tradition," with Fyodor Dostoyevsky as the best-known example. The importance of prison literature lies in its reflection of social conditions. Texts – especially those written by those imprisoned for political reasons, and in this particular case the poetry of Peter-Paul Zahl – served not only as an attempt to survive but also as a resistance to institutional violence.[68]

Zahl's poem Prisoner's Dream is also interpreted in this sense:

pack

your things

You will be

released immediately

Your judge

has confessed[69]

Prison poetry offers a chance to learn about the inner world of prisons, but at the same time there is a danger of blurring the lines between right and wrong, judge and defendant, "outside" and "inside.[70]

Inspired by this debate, Helmut H. Koch, a professor of German studies, took up the topic of "obviously explosive literature," founded the Documentation Center for Prisoner Literature at the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster in the early 1980s, and is the co-initiator of the Ingeborg Drewitz Prize for Prisoner Literature, which was established in 1988.[71] Koch sees prison literature as a necessary complement to established literature to make visible the reality of prisons, which is largely ignored by society.[72]

Work and indolence

[edit]

In an essay published posthumously in 1980, Rudi Dutschke, one of the most prominent spokespersons of the APO, compared some aspects of the work of the Vormärz writer Georg Büchner with that of Peter-Paul Zahl. He saw both as radical oppositional poets who had created a literature of resistance. Zahl had been influenced by Büchner's existentialist understanding of resistance, which he had developed at an early age.[73] In contrast, he described Zahl's early poetry as "existentialist resistance poetry, essentially individualistic.[74] In the period after 1968, Zahl's importance lay in his role as a chronicler of the anti-authoritarian movement. His publications, and even more so his life story, made it possible to relativize and concretize one's view of one's own history.[75]

In addition to comparing the two writers' positions on revolutionary defeats and questions of love, Dutschke's essay focuses on their examination of work as a social category. In his work, Büchner often takes an anticipatory stand against wage slavery; the question is whether Zahl's comments on happy unemployment are to be understood in the same sense as precursors of future working methods. He cites Büchner as an example:

"Our life is murder by work; we hang on the rope for sixty years and struggle, but we will cut ourselves loose!"

— Georg Büchner, Dichtungen[76]

Zahl takes up this radical negation of work in general and wage labor in particular. The alienated and oppressive process is already present in the description of work processes in the novel From Someone Who Set Out to Earn Money, and the language of Büchner's worker types echoes in it:

"… ... if you're lucky, you'll be with yourself, but you'll probably be too tired."

— Peter-Paul Zahl, From someone who set out to earn money[77]

Dutschke stated that "a voice was heard in this novel that did not correspond to the conventional name of 'student movement,' which was promoted in a dominant and class-conscious manner.''[78]

Zahl's view of the refusal to work as a fundamental condition for the liberation of human developmental needs is even clearer in his essay Indolence instead of/or work, which stands in the best tradition of Büchner, but also of Paul Lafargue's The Right to Be Lazy. Zahl tried to link Lafargue and Bakunin with Marx and Engels, which earned him the accusation of subjectivism from parts of the Marxist left. Dutschke accused them of not knowing the categories of life and leisure time in Marx's work.

In the novel Die Glücklichen, Zahl explicitly and centrally refers to Büchner's understanding of work and indolence. With the closing words from the comedy Leonce and Lena, he introduces the narrative of a permissive, free-spirited, pleasure-oriented concept of life of the protagonists, who practice anarcho-libertarian socialism and oppose rigorous dogmatism:[79]

"We will have all clocks smashed, all calendars forbidden, and we will count hours and moons only by the flower clock, only by blossom and fruit. [...] and a decree will be issued that anyone who forms calluses on his hands will be placed under curatorship; anyone who works himself sick will be criminally punished; anyone who prides himself on eating his bread by the sweat of his brow will be declared insane and dangerous to human society."

— Georg Büchner, Leonce und Lena [80]

Dutschke remarked on this quotation that Büchner fundamentally transcends petite bourgeoisie thinking in the Marxist sense.[81] The literary scholar Sandra Beck takes up this comparison and explains that Zahl thus opens up an intertextuality and places the alternative described in a fairy-tale world, very much in the tradition of Büchner's fairy-tale play. Failure is anticipated because the protagonists are not removed from time, but find themselves in a conflicted relationship with the outside world. This "undermines the concrete ideal in the recourse to Büchner's The Hessian Courier.[82]

Musical reception

[edit]In October 1978, musicians from the Viennese band Schmetterlinge and the Hamburg political rock group Oktober set texts from Zahl's 1977 poetry collection All Doors Open to music and recorded an album. In addition to six songs, flamenco guitarist Miguel Iven recorded the twenty-minute piece Ninguneo, a musical text about the assassination of poet Federico García Lorca. Participating musicians included Kalla Wefel, Andreas Hage, Beatrix Neundlinger, Ali Husseini, and Willi Resetarits.[83]

Hamburg musician Achim Reichel set Zahl's poem Bessie kommt to music on his 1980 album Ungeschminkt. Composers Holger Münzer and Heiner Goebbels are also known to have set Zahl's texts to music.

The band Das Lunsentrio released the song Reggae for Peter-Paul Zahl on the album 69 ways to play pub rock in 2021.

See also

[edit]Work overview (Selection)

[edit]Poetry and short story collections

[edit]

|

|

Novels and stage works

[edit]

|

|

Crime novels in the Fraser series

[edit]

|

|

More prose

[edit]

|

|

Radio plays and records

[edit]- Lyrik und Jazz, 1980

- Sumpf, 1982

- Rollberg, SFB, 1984 (Radio play)

- Macht hoch die Tür …, 1985

Translations

[edit]- Victor Serge: Geburt unserer Macht (Original title: Naissance de notre force), Tricont, Munich 1976, ISBN 3-920385-93-4.

- Otto René Castillo: Selbst unter der Bitterkeit, Poems (Original title: Aun bajo la amargura Co-translator: Reinhard Thoma), Information point Guatemala, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-923872-00-3 (Contains: Only those who love are consistent).

- Ramón José Sender: Sieben rote Sonntage (Original title: Siete Domingos rojos), Rotpunkt, Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-85869-063-5.

Prizes and awards

[edit]- 1979/1980: Literature Prize of the city of Bremen

- 1995: Friedrich Glauser Prize of the "Authors' group for German-language crime fiction" – The Syndicate

- 1998: Scholarship from the state of North Rhine-Westphalia

The building of the Department of German Studies, which was occupied during a lecture strike at the Free University of Berlin in the winter semester of 1976/77, was temporarily renamed the Peter-Paul-Zahl-Institut as part of this action. In the following years, the Political Science Forum at the Peter-Paul-Zahl-Institut and the KSV cell at the Peter-Paul-Zahl-Institute of the Free University of Berlin published several publications under this name, so that the name was retained.[84]

Bibliography

[edit]- Sandra Beck: Reden an die Lebenden und die Toten. Erinnerungen an die Rote Armee Fraktion in der deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur. Mannheim Studies in Literature and Cultural Studies, Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert 2008, ISBN 978-3-86110-443-8, P. 35–51; Available, p. 35, at Google Books

- Gretchen Dutschke (Ed.): Mut und Wut: Rudi Dutschke und Peter Paul Zahl; Briefwechsel 1978/79. Publisher M – Stadtmuseum Berlin, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-939254-01-0.

- Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner und Peter-Paul Zahl, oder: Widerstand im Übergang und mittendrin. In: Georg Büchner Jahrbuch, 4/84, Walter de Gruyter Publisher, Berlin 1984, p. 9–75.

- Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak, Initiative group P.P. Zahl (ed.): Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Socialist publishing house, Frankfurt 1976 ff.

- Erich Fried: Von einem, der nicht relevant ist: über das Risiko, sich mit der Literatur P.P. Zahls auseinanderzusetzen. In: Manfred Belting (Ed.): Schriftenreihe zeitgeschichtliche Dokumentation. 2nd year, issue 8/9, SZD publisher, Münster 1979.

- Initiativgruppe P.P. Zahl: Der Fall Peter-Paul Zahl. Berichte u. Dokumente in 3 Sprachen. Publisher Neue Kritik, Frankfurt am Main 1978.

- Tobias Lachmann: Peter-Paul Zahl – Eine politische Schreibszene. In: Ute Gerhard, Hanneliese Palm (Ed.): Schreibarbeiten an den Rändern der Literatur. Die Dortmunder Gruppe 61. Essen 2012, p. 43–88.

References

[edit]- ^ The Publishing House of Peter Paul in Feldberg – a bibliography, Mecklenburg-Strelitz Blog, May 28, 2011

- ^ Christoph Links: Die verschwundenen Verlage der SBZ/DDR: Zwischenbericht zu einem Forschungsprojekt. In: Björn Biester, Carsten Wurm (Ed.): 2016. Archive for the History of the Book Trade, Volume 71, p. 235–260. doi:10.1515/9783110462227-009, pirckheimer-gesellschaft.org (PDF; 531 kB)

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl: Lebenslauf einer Unperson. In: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Eine Dokumentation. 3rd edition. 1978, p. 15-48, here p. 27

- ^ Judgment of the Düsseldorf Regional Court of March 12, 1976, reprinted in: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Eine Dokumentation. pp. 86–101, here p. 87

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl in a letter to Rudi Dutschke, March 24–25, 1978: Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner und Peter-Paul Zahl, oder: Widerstand im Übergang und mittendrin. In: Georg Büchner Jahrbuch. Berlin 1984, p. 37

- ^ See Agit 883 ....

- ^ Cf. Zahl, Peter-Paul. In: Walter Habel (Ed.): Wer ist wer? Das deutsche Who’s who. 24th edition. Schmidt-Römhild, Lübeck 1985, ISBN 3-7950-2005-0, p. 1377.

- ^ Gregor Dotzauer: Peter-Paul Zahl: Das System ist der Fehler. In: Tagesspiegel from January 25, 2011, retrieved on March 9, 2012.

- ^ Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner und Peter-Paul Zahl, oder: Widerstand im Übergang und mittendrin. p. 39

- ^ Spartacus: zeitschrift für lesbare literatur – DNB 011172142 – catalog entry of the German National Library

- ^ pp-quadrat – catalog of the German National Library; accessed on March 9, 2012

- ^ zwergschul-ergänzungshefte – DNB 458748331 – catalog entry of the German National Library

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl: Lebenslauf einer Unperson. In: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Eine Dokumentation. p. 37

- ^ Fizz. Der kurze Sommer der gedruckten Anarchie – oder die Notwendigkeit klandestiner Zeitungen. On haschrebellen.de, accessed March 24, 2012

- ^ Image of the poster designed by Holger Meins at the end of April 1970 and published at the beginning of May on palestineposterproject.org, accessed on May 28, 2012

- ^ Heinrich Hannover: Die Republik vor Gericht. 1954–1974. Erinnerungen eines unbequemen Rechtsanwalts. Aufbau Taschenbuch Publisher, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7466-7031-4, p. 410

- ^ Heinrich Hannover: Die Republik vor Gericht. 1954–1974. Erinnerungen eines unbequemen Rechtsanwalts. Berlin 2000, p. 411

- ^ a b Bedauert nicht. In: Der Spiegel. No. 7, 1980, p. 80-82 (online).

- ^ a b Heinrich Hannover: Die Republik vor Gericht. 1954–1974. Erinnerungen eines unbequemen Rechtsanwalts. Berlin 2000, p. 412

- ^ a b Gerhard Mauz: Ich wollte nicht um jeden Preis fliehen. In: Der Spiegel. No. 24, 1977, pp. 99–103 (online).

- ^ Judgment of the Federal Court of Justice of July 29, 1975 (3 STR 119/75), reprinted in: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Eine Dokumentation. P. 81-85, here p. 83

- ^ Judgment of the Düsseldorf Regional Court of March 12, 1976, reprinted in: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Eine Dokumentation. P. 86-101, here p. 96.

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl: Strafrecht oder Gesinnungsjustiz. Closing statement in court, Düsseldorf March 12, 1976, reprinted in: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Eine Dokumentation. P. 103–121, here p. 117.

- ^ Judgment of the Düsseldorf Regional Court dated March 12, 1976, reprinted in: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Eine Dokumentation. P. 100.

- ^ a b c Fritz J. Raddatz: Nachdenken über Peter-Paul Zahl. Von der Befragbarkeit der Justiz. In: Die Zeit from February 10, 1977, retrieved on March 31, 2012

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl: im namen des volkes. In: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: The example of Peter-Paul Zahl. A documentation. p. 165 f.

- ^ Erbrochene Worte. In: Die Zeit, No. 34/1978

- ^ Decision of the Düsseldorf Regional Court of August 21, 1974, reprinted in: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Eine Dokumentation. p. 149

- ^ Narren aus der Zelle. In: Der Spiegel. No. 7, 1980, p. 197–198 (online).

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl: Johann Georg Elser. Ein deutsches Drama. In: Schauspielhaus Bochum (ed.): Programmbuch. No 31. Schauspielhaus Bochum, Bochum 1982.

- ^ a b Thomas Pampuch: Der Halbjamaikaner. In: taz, January 25, 2011, retrieved on April 3, 2012

- ^ http://www.inkrit.de/argument/archiv/DA151.pdf (link not available)

- ^ Ernst Volland: Peter Paul Zahl, Interview spring 1994, published on blogs.taz.de on January 27, 2011, retrieved on March 27, 2012.

- ^ Author Peter-Paul Zahl, on the website of the publisher C. H. Beck, retrieved on March 27, 2012

- ^ Loss of German citizenship (Memento from March 19, 2015, in the Internet Archive), Federal Government Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration

- ^ Michael Sontheimer: Der Pass des Anarchisten. Spiegel Online, May 5, 2004; retrieved on March 27, 2012

- ^ Otto Diederichs: Peter Paul Zahl wieder Deutscher. In: taz from April 24, 2006, retrieved on March 27, 2012

- ^ a b Jörg Sundermeier: Schriftsteller Peter-Paul Zahl gestorben: Kein Heros vom Establishment. In: taz, January 25, 2011, retrieved on March 29, 2012

- ^ a b Gabriele Dietze: Der Bad Boy der deutschen Literaturszene. Schriftsteller Peter-Paul Zahl ist tot. Germany Radio Culture, interview; retrieved on March 31, 2012

- ^ a b Wolfgang Harms: Anti-Autoritärer Aussteiger. Autor Peter-Paul Zahl wird 65 – Ein Porträt. In: Die Berliner Literaturkritik. March 12, 2009, retrieved on March 16, 2012

- ^ a b Hans W. Korfmann: Peter-Paul Zahl, author. In: Kreuzberger Chronik. 2002, retrieved on March 16, 2012

- ^ Ernst Toller: Das Schwalbenbuch

- ^ Society for the Promotion of the Frankfurt Hölderlin Edition (ed.): Le Pauvre Holterling: Sheets for the Frankfurt Edition No. 1 Publisher Roter Stern, Frankfurt 1976

- ^ DHM dataset: Peter Paul Zahl: Professional ethics and DHM dataset: Peter Paul Zahl: The chimney mason, retrieved on March 16, 2012

- ^ Politische Ahnung. Peter-Paul Zahl: „Von einem der auszog, Geld zu verdienen“. In: Der Spiegel. No. 53, 1970, p. 84-85 (online).

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl: Nachwort zu Georg Büchner. Georg Büchner. Der Hessische Landbote. In: zwergschul-ergänzungsheft, No. 4, 1968, quoted from: Dietmar Goltschnigg (ed.): Georg Büchner und die Moderne. Texts, analyses, commentary; Volume II: 1945–1980. Erich Schmidt Publisher, Berlin 2002, ISBN 978-3-503-06106-8, p. 12 f.

- ^ Michael Buselmeier: Bemerkungen zu Peter-Paul Zahl: „Schutzimpfung“. In: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: Am Beispiel Peter-Paul Zahl. Eine Dokumentation. P. 175 f.

- ^ from: Peter-Paul Zahl: Vaccination. In: Erich Fried, Helga M. Novak: The example of Peter-Paul Zahl. A documentation. p. 176

- ^ a b c Enno Stahl: Literatur und Terror. RAF-Rezeption in Romanen der letzten 25 Jahre. September 2003, retrieved on March 30, 2012

- ^ Sandra Beck: Reden an die Lebenden und die Toten. Erinnerungen an die Rote Armee Fraktion in der deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur. Mannheim Studies in Literary and Cultural Studies, p. 40

- ^ a b Harry Nutt: Freiheit und Glück als Signatur. In: Frankfurter Rundschau from January 26, 2011, retrieved on March 31, 2012

- ^ Sabine Peters: Ein linker Schelmenroman. In: Deutschlandfunk from June 16, 2010, retrieved on March 16, 2012

- ^ Christine Axer: Linksalternatives Milieu und Neue Soziale Bewegungen in den 1970er Jahren. Akademiekonferenz für den wissenschaftlichen Nachwuchs. University of Heidelberg, September 2009, H-Soz-u-Kult, accessed March 31, 2012

- ^ Das Theater entdeckt Georg Elser. (Memento from June 3, 2012 in the Internet Archive; PDF; 51 kB) Website of the Georg Elser Working Group Heidenheim; retrieved on January 18, 2013

- ^ Der Bombenbastler. In: Der Spiegel. No. 9, 1982, p. 227–229 (online).

- ^ Fritz, a German Hero oder Nr. 477 bricht aus. (Memento of October 29, 2009, in the Internet Archive), Entry in the catalog of works of the Association of German Stage and Media Publishers, theatertexte.de, March 27, 2001

- ^ Martin Halter: Terror in Entenhausen. Uraufführung von Peter-Paul Zahls „Die Erpresser“. In: taz from December 5, 1990

- ^ Jörg Witta: Ungesunde Suche nach Talenten. In: Berliner Lesezeichen. Edition Luisenstadt, May 1997 issue, retrieved on March 30, 2012

- ^ Maike Albath: Witz komm raus. Peter-Paul Zahl raubt den Kölner Domschatz. In: Die Süddeutsche, July 22, 2002, buecher.de, retrieved on March 29, 2012

- ^ Anarcho-Autor Peter-Paul Zahl gestorben. In: Welt Online from January 26, 2011, retrieved on March 29, 2012

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl: Mittel der obrigkeit. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from May 22, 1976

- ^ Marcel Reich-Ranicki, Golo Mann: Enthusiasten der Literatur. Ein Briefwechsel. Fischer Publisher, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-10-062813-6.

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl: Die Glücklichen. Roguish novel. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Publisher, Reinbek 1986, ISBN 3-499-15683-0, p. 365.

- ^ Sandra Beck: Reden an die Lebenden und die Toten. Erinnerungen an die Rote Armee Fraktion in der deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur. Mannheim Studies in Literary and Cultural Studies, p. 37.

- ^ a b Sandra Beck: Reden an die Lebenden und die Toten. Erinnerungen an die Rote Armee Fraktion in der deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur. Mannheim Studies in Literary and Cultural Studies, p. 46.

- ^ Initiativgruppe P.P. Zahl (Frankfurt am Main) Archives. on the website of the International Institute of Social History, accessed March 25, 2012

- ^ Erich Fried, quoted in: Haft-Schäden. In: Die Zeit, No. 42/1979

- ^ Erich Fried: Von einem, der nicht relevant ist: Über das Risiko, sich mit der Literatur P.P. Zahls auseinanderzusetzen, Speech from January 12, 1979. In: Manfred Belting (Ed.): Schriftenreihe zeitgeschichtliche Dokumentation. Münster 1979.

- ^ Peter Paul Zahl: Häftlingstraum. In: All doors open. Berlin 1977

- ^ Nicola Kessler: Der Ingeborg-Drewitz-Literaturpreis für Gefangene. In: Barbara Becker-Cantarino, Inge Stephan (Hrsg.): „Von der Unzerstörbarkeit des Menschen“. Ingeborg Drewitz im literarischen und politischen Feld der 50er bis 80er Jahre. Berne 2005, ISBN 3-03910-429-2, P. 130; available in the Google book search

- ^ Dokumentationsstelle Gefangenenliteratur – Knastliteratur (Memento from December 23, 2013, in the Internet Archive), retrieved on March 31, 2012

- ^ Helmut H. Koch: Schreiben und Lesen in sozialen und psychischen Krisensituationen – eine Annäherung. In: Johannes Berning, Nicola Keßler, Helmut H. Koch: Schreiben im Kontext von Schule, Universität, Beruf und Lebensalltag. Berlin and Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-9260-3, p. 128-135; available in the Google Book Search

- ^ Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner und Peter-Paul Zahl, oder: Widerstand im Übergang und mittendrin. P. 11.

- ^ Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner und Peter-Paul Zahl, oder: Widerstand im Übergang und mittendrin. P. 38.

- ^ Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner und Peter-Paul Zahl, oder: Widerstand im Übergang und mittendrin. P. 40.

- ^ Georg Büchner, here quoted from: Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner and Peter-Paul Zahl, or: resistance in transition and in the midst of it. P. 51.

- ^ Peter-Paul Zahl: Von einem der auszog, Geld zu verdienen, Düsseldorf 1970, p. 50, here quoted from: Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner und Peter-Paul Zahl, oder: Widerstand im Übergang und mitmittendrin. P. 54.

- ^ Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner und Peter-Paul Zahl, oder: Widerstand im Übergang und mittendrin. P. 54.

- ^ Sandra Beck: Reden an die Lebenden und die Toten. Erinnerungen an die Rote Armee Fraktion in der deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur. Mannheim Studies in Literature and Cultural Studies, p. 42.

- ^ Georg Büchner: Leonce und Lena, here quoted from: Peter-Paul Zahl: Die Glücklichen. Schelmenroman. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Publisher, p. 153.

- ^ Rudi Dutschke: Georg Büchner und Peter-Paul Zahl, oder: Widerstand im Übergang und mittendrin. P. 52.

- ^ Sandra Beck: Reden an die Lebenden und die Toten. Erinnerungen an die Rote Armee Fraktion in der deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsliteratur. Mannheim Studies in Literature and Cultural Studies, p. 44.

- ^ Zero G Sound: Alle Türen offen. March 24, 2011, retrieved on May 21, 2019

- ^ Political Science Forum at the Peter-Paul-Zahl-Institute (ed.) Kernbeisser. Self-published, Berlin 1978–1981 or KSV cell at the Peter-Paul-Zahl-Institut Freie Universität Berlin (ed.): Wohin geht die Germanistik? (Blasting sets No. 2, May 1978).

External links

[edit]- Peter-Paul Zahl in the German National Library catalogue

- Inventory overview Peter-Paul Zahl. deutsches literaturarchiv marbach

- Article about an event with Peter-Paul Zahl in 2002. Kreuzberg Chronicle

- Peter-Paul Zahl Archive of the Spiegel Group