People linked to Anwar al-Awlaki

Anwar al-Awlaki (also spelled Aulaqi) was an American-Yemeni cleric killed in late 2011, who was identified in 2009 by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) as a known, important "senior recruiter for al Qaeda", and a spiritual motivator.

[1][2] Al-Awlaki's name came up in the context of a dozen terrorism plots in the US, UK, and Canada. The cases included suicide bombers in the 2005 London bombings, radical Islamic terrorists in the 2006 Toronto terrorism case, radical Islamic terrorists in the 2007 Fort Dix attack plot, and Faisal Shahzad, charged in the 2010 Times Square attempted bombing. In each case the suspects demonstrated devotion to al-Awlaki's message, as they listened to his lectures and sermons on laptops, audio clips, and CDs.[3][4][5][6]

Al-Awlaki’s recorded lectures appeared to inspire Islamist fundamentalists who comprised at least six terror cells in the UK through 2009.[7] Michael Finton (Talib Islam), who attempted in September 2009 to bomb the Federal Building and the adjacent offices of Congressman Aaron Schock in Springfield, Illinois, admired al-Awlaki and quoted him on his Myspace page.[8] In addition to his website, al-Awlaki had a Facebook fan page.[9] A substantial percentage of fans were from the US and identified as high school students.[10]

In October 2008, Charles Allen, U.S. Undersecretary of Homeland Security for Intelligence and Analysis, warned that al-Awlaki "targets U.S. Muslims with radical online lectures encouraging terrorist attacks from his new home in Yemen."[11][12] Responding to Allen, Al-Awlaki wrote on his website in December 2008: "I would challenge him to come up with just one such lecture where I encourage 'terrorist attacks'".[13]

9/11 attacks

[edit]Khalid al-Mihdhar was one of the five hijackers of American Airlines Flight 77, which was flown into the Pentagon as part of the September 11 attacks. While in San Diego, witnesses told the FBI Mihdhar and fellow hijacker Nawaf al-Hazmi had a close relationship with Anwar Al Awlaki, an imam who served as their spiritual advisor.[14] Authorities say the two regularly attended the Masjid Ar-Ribat al-Islami mosque Awlaki led in San Diego, and Awlaki had many closed-door meetings with them, which led investigators to believe Awlaki knew about the 9/11 attacks in advance.

Anwar al-Awlaki headed east and served as Imam at the Dar al-Hijrah mosque in the metropolitan Washington, DC area starting in January 2001.[15] Shortly after this, his sermons were attended by three of the 9/11 hijackers including Hazmi.[16][17] The 9/11 Commission concluded that two of the hijackers "reportedly respected Awlaki as a religious figure".[1] Police found his telephone number in the contacts of Ramzi bin al-Shibh (the "20th hijacker") when they searched his Hamburg apartment while investigating the 9/11 attacks.[18][19] The imam's precise role in the September 11 attack remains a painful, unanswered question for many Americans when he shows up so frequently in a timeline of events.[20] In 2011, the House Homeland Security Committee investigated whether Anwar al-Awlaki might have contributed to the 9/11 attacks. [21]

Little Rock military recruiting office shooting (June 2009)

[edit]In the 2009 Little Rock military recruiting office shooting, Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad, formerly known as Carlos Leon Bledsoe, a convert to Islam who had spent time in Yemen, on June 1, 2009 opened fire with an assault rifle in a drive-by shooting on soldiers in front of a United States military recruiting office in Little Rock, Arkansas. He killed Private William Long and wounded Private Quinton Ezeagwula. Muhammad claimed to be affiliated with and sent by Al-Qaeda.[22][23][24] He had previously been arrested in Yemen in November 2008, with a fraudulent Somali passport, explosive manuals, and literature by al-Awlaki.[25]

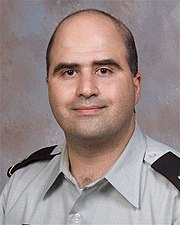

Fort Hood shooter (November 2009)

[edit]

Nidal Malik Hasan

Shooting suspect Nidal Malik Hasan was investigated by the FBI after intelligence agencies intercepted at least 18 emails between him and al-Awlaki between December 2008 and June 2009.[26] The terrorism expert Jarret Brachman said that Hasan's contacts with al-Awlaki should have raised "huge red flags" to intelligence analysts. According to Brachman, the late al-Awlaki was a major influence on radical English-speaking jihadis internationally.[27] The Wall Street Journal reported that "There is no indication Mr. Awlaki played a direct role in any of the attacks, and he has never been indicted in the U.S."[28]

In one of the emails, Hasan wrote al-Awlaki: "I can't wait to join you [in the afterlife]". "It sounds like code words," said Lt. Col. Tony Shaffer, a military analyst at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies. "That he's actually either offering himself up, or that he's already crossed that line in his own mind." Hasan also asked al-Awlaki when jihad is appropriate, and whether it is permissible if innocents are killed in a suicide attack.[29] In the months before the attacks, Hasan increased his contacts with al-Awlaki to discuss how to transfer funds abroad without coming to the attention of law authorities.[26]

A DC-based Joint Terrorism Task Force operating under the FBI was notified of the emails, and reviewed the information. Army employees were informed of the emails, but they didn't perceive any terrorist threat in Hasan's questions, as the psychiatrist was researching issues related to potential conflicts of Muslims related to serving in the military. He was completing a master's degree in public health in "Disaster and Preventive Psychiatry".[30] The assessment was that there was not sufficient information for a larger investigation.[31]

Blog and website

[edit]Al-Awlaki had set up a website, with a blog on which he shared his views.[32] On December 11, 2008, he condemned any Muslim who seeks a religious decree "that would allow him to serve in the armies of the disbelievers and fight against his brothers."[32]

In "44 Ways to Support Jihad," another sermon posted on his blog in February 2009, al-Awlaki encouraged others to "fight jihad", and explained how to give money to the mujahideen or their families after they have died. Al-Aulaqi's sermon encouraged followers to get weapons training, and raise children "on the love of Jihad."

[33] That month, he wrote: "I pray that Allah destroys America and all its allies."[32] He wrote: "We will implement the rule of Allah on Earth by the tip of the sword, whether the masses like it or not."[32] On July 14, he criticized armies of Muslim countries that assist the U.S. military, saying, "the blame should be placed on the soldier who is willing to follow orders ... who sells his religion for a few dollars."[32] In a sermon on his blog on July 15, 2009, entitled "Fighting Against Government Armies in the Muslim World," al-Awlaki wrote, "Blessed are those who fight against [American soldiers], and blessed are those shuhada [martyrs] who are killed by them."[33][34]

A fellow Muslim officer at Fort Hood said Hasan's eyes "lit up" when he talked about al-Awlaki's teachings.[35] Some investigators believe that Hasan's contacts with al-Aulaqi are what pushed him toward violence.[36] Others think his personal psychological problems and an apparently fragile emotional state, which were discussed for years by colleagues and superiors, were more significant.

After the Fort Hood shooting, on his now temporarily inoperable website (apparently because some web hosting companies took it down),[5] al-Awlaki praised Hasan's actions:

Nidal Hassan is a hero.... The U.S. is leading the war against terrorism, which in reality is a war against Islam..... Nidal opened fire on soldiers who were on their way to be deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. How can there be any dispute about the virtue of what he has done? In fact the only way a Muslim could Islamically justify serving as a soldier in the U.S. army is if his intention is to follow the footsteps of men like Nidal.

The fact that fighting against the US army is an Islamic duty today cannot be disputed. No scholar with a grain of Islamic knowledge can defy the clear cut proofs that Muslims today have the right—rather the duty—to fight against American tyranny. Nidal has killed soldiers who were about to be deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan in order to kill Muslims. The American Muslims who condemned his actions have committed treason against the Muslim Ummah and have fallen into hypocrisy.... May Allah grant our brother Nidal patience, perseverance, and steadfastness, and we ask Allah to accept from him his great heroic act. Ameen.[37][38]

Yemeni journalist Abdulelah Hider Shaea interviewed al-Awlaki in November 2009.

[39] Al-Awlaki acknowledged his correspondence with Hasan. He said he "neither ordered nor pressured ... Hasan to harm Americans". Al-Awlaki said Hasan first e-mailed him December 17, 2008, introducing himself by writing: "Do you remember me? I used to pray with you at the Virginia mosque." Hasan said he had become a devout Muslim around the time al-Aulaqi was preaching at Dar al-Hijrah, in 2001 and 2002, and al-Aulaqi said 'Maybe Nidal was affected by one of my lectures.'" He added: "It was clear from his e-mails that Nidal trusted me. Nidal told me: 'I speak with you about issues that I never speak with anyone else.'" Al-Aulaqi said Hasan arrived at his own conclusions regarding the acceptability of violence in Islam, and said he was not the one to initiate this. Shaea said, "Nidal was providing evidence to Anwar, not vice versa."[39]

Asked whether Hasan mentioned Fort Hood as a target in his e-mails, Shaea declined to comment. However, al-Awlaki said the shooting was acceptable in Islam because it was a form of jihad, as the West began the hostilities with the Muslims.[40] Al-Aulaqi said he "blessed the act because it was against a military target. And the soldiers who were killed were ... those who were trained and prepared to go to Iraq and Afghanistan".[39][41]

Al-Awlaki released a tape in March 2010, in which he said, in part:

- To the American people ... Obama has promised that his administration will be one of transparency, but he has not fulfilled his promise. His administration tried to portray the operation of brother Nidal Hasan as an individual act of violence from an estranged individual. The administration practiced to control on the leak of information concerning the operation, in order to cushion the reaction of the American public.

- Until this moment the administration is refusing to release the e-mails exchanged between myself and Nidal. And after the operation of our brother Umar Farouk, the initial comments coming from the administration were looking the same – another attempt at covering up the truth. But Al Qaeda cut off Obama from deceiving the world again by issuing their statement claiming responsibility for the operation.[42]

In addition to the point made by al-Awlaki himself about the failure to release his emails, despite wide press coverage of al-Awlaki's role as a spiritual guide to Hasan, and many previous anti-terrorism investigations dating back pre-9/11, al-Aulaqi has not been placed on an FBI Most Wanted or other terror list, indicted for treason, or publicly named as a co-conspirator with Hasan. The US government has been reluctant to classify the Fort Hood shooting as a terrorist incident, or to identify Hasan's motive.

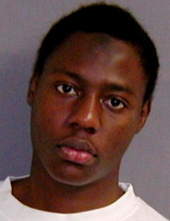

Christmas Day bomber (December 2009)

[edit]

Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab (Arabic عمر فاروق عبد المطلب) (also referred to as Umar Abdul Mutallab and Omar Farooq al-Nigeri; born December 22, 1986, Lagos),[43][44] popularly referred to as the "Underwear Bomber", is a Nigerian man who, at the age of 23, confessed to and was convicted of attempting to detonate plastic explosives hidden in his underwear while on board Northwest Airlines Flight 253, en route from Amsterdam to Detroit, Michigan, on December 25, 2009.[44][45]

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula claimed to have organized the attack with Adbulmutallab and said they supplied him with the bomb and trained him.

He was convicted of eight criminal counts, including attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction and attempted murder of 289 people. On February 16, 2012 he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole by a U.S. federal court.[46]

Sharif Mobley (March 2010)

[edit]Alleged al-Qaeda member Sharif Mobley, who is charged with having killed a guard during a March 2010 escape attempt in Yemen, left his home in New Jersey to seek out al-Awlaki, hoping that Awlaki would become his al-Qaeda mentor, according to senior U.S. security officials as reported by CNN.[47] He was in contact with al-Awlaki, according to officials from the U.S. and Yemen, The New York Times reported.[48] A Yemeni embassy spokesman in Washington, D.C., said he was not surprised by al-Aulaqi's apparent links to Mobley, calling al-Aulaqi: "a fixture in jihad 101."[49]

Paul and Nadia Rockwood (April 2010)

[edit]Paul Rockwood is an Alaskan man and a follower of al-Awlaki. According to US Attorney Karen L. Loeffler, he "held a personal conviction that it was his religious responsibility to exact revenge by death on anyone who desecrated Islam, and he began researching possible targets for execution." Her report to the United States Department of Justice states that he became a strict adherent to the violent jihad ideology of Al-Awlaki. He compiled a hit-list of 15 targets as well as possible methods, including mail bombs and gunshots to the head.[50][51] He gave the list to his wife, Nadia, in April 2010 and she delivered the list to Anchorage, Alaska, where it was obtained by the FBI.[52] In a plea agreement, the couple pleaded guilty to lying to FBI investigators.[50][52]

Zachary Adam Chesser (April 2010)

[edit]Zachary Adam Chesser (also known as Abu Talhah al-Amrikee) is an American man in Fairfax County, Virginia, who has been accused of aiding a terrorist organization.[53] In April 2010, he posted a "warning" to the creators of the animated TV series South Park, suggesting that they would be killed for depicting Muhammad in their 200th episode.[54] In July 2010, he was arrested on charges of aiding Al-Shabaab, which has been designated a terrorist organization by the U.S. government. Court records say that he had become intrigued by al-Awlaki's teachings and corresponded with the cleric by email.[53]

Times Square bomber (May 2010)

[edit]Faisal Shahzad, convicted of the attempted car bombing of Times Square in May 2010, told interrogators that he was "inspired by" al-Awlaki. Shahzad reportedly said he was moved to action, at least in part, by al-Awlaki's English-language writings calling for holy war against Western targets, and he was a "fan and follower" of al-Aulaqi, according to sources.[55][56] Shahzad made contact over the internet with al-Aulaqi, ABC News reported.[57][58]

Roshonara Choudhry (May 2010)

[edit]Roshonara Choudhry is a British Muslim woman who, after listening to al-Awlaki's English-language sermons online, decided to attack politicians she felt were involved in the persecution of Muslims in Iraq. After researching voting records, she attacked MP Stephen Timms with a kitchen knife on May 14, 2010 and stabbed him twice before being subdued. The investigation of the attack was handled by the counter-terrorism command at Scotland Yard after the connection to al-Awlaki was discovered, but they found no evidence of any direct contact with al-Aulaqi or any other radicals. Choudhry was convicted of attempted murder and weapon possession.[59]

Barry Walter Bujol (May 2010)

[edit]

Barry Walter Bujol Jr., an African American from Hempstead, Texas, was arrested and charged by the U.S. government in May 2010 with trying to provide money and equipment to al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.[60] Court documents alleged that he exchanged email with and received advice from al-Awlaki over a period of several months in 2008, including advice on how to help al-Qaeda and how to start a jihadi website that could not be traced.[61][62] Al-Awlaki also sent him a copy of his tract entitled 42 Ways of Supporting Jihad.[61][62][63]

Mohamed Haoud Alessa and Carlos Eduardo Almonte (June 2010)

[edit]Mohamed Haoud Alessa and Carlos Eduardo Almonte were arrested on June 6, 2010 at Kennedy International Airport en route to Somalia allegedly for the purpose of joining "an Islamic extremist group and to kill American troops",[64] although few American troops are stationed any longer in Somalia. The two men were waiting to board separate flights to Egypt en route to Somalia where they hoped to join the Shabaab militant group.[64] Both men are American citizens[65] and had been under investigation by the FBI since 2006, when Alessa was still a teenager. Each was charged with a "single count of conspiracy to kill, kidnap, maim, or injure persons or damage property in a foreign country".[64] The two men viewed a number of audio and video recording promoting violent Jihad, including lectures by al-Awlaki, in the presence of an undercover officer.[64] If convicted, the two were likely to face a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.[64] Both pleaded guilty to the charges on 3 March 2011 in the Newark Federal Court.[66]

Chattanooga military recruiting office and reserve center shooting (July 2015)

[edit]On July 16, 2015, Mohammad Youssef Abdulazee opened fire at an armed forces recruiting center and Navy Operational Support Center in Chattanooga, Tennessee, killed 4 Marines and 1 Sailor. The cause of the shooting is still under investigation.

During the ongoing investigation, law enforcement officials revealed that Abdulazee had downloaded al-Awlaki's teachings and had several CDs.[67]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Allam, Hannah (November 22, 2009). "Is imam a terror recruiter or just an incendiary preacher?". Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on November 24, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ^ Chucmach, Megan; Brian Ross (November 10, 2009). "Al Qaeda Recruiter New Focus in Fort Hood Killings Investigation". ABC News. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Rhee, Joseph; Mark Schone (November 30, 2009). "How Anwar Awlaki Got Away". The Blotter from Brian Ross; Fort Hood Investigation. ABC News. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ Shane, Scott; Souad Mekhennet (May 8, 2010). "Anwar al-Awlaki – From Condemning Terror to Preaching Jihad". New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Shane, Scott (November 18, 2009). "Born in U.S., a Radical Cleric Inspires Terror". New York Times. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ Sherwell, Philip; Duncan Gardham (November 23, 2009). "Fort Hood shooting: radical Islamic preacher also inspired July 7 bombers". Telegraph (UK). London. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ McDougall, Dan; Claire Newell; Christina Lamb; Jon Ungoed-Thomas; Chris Gourlay; Kevin Dowling; Dominic Tobin (January 3, 2010). "Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab: one boy's journey to jihad". The Sunday Times (UK). London. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Gruen, Madeleine (December 2009). "Attempt to Attack the Paul Findley Federal Building in Springfield, Illinois" (PDF). Report #23 in the 'Target: America' Series. The NEFA Foundation. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Anwar al-Awlaki. "Facebook page" (Screen capture). Unknown.

- ^ NEFA Foundation staff (February 5, 2009). "Anwar al Awlaki: Pro Al-Qaida Ideologue with Influence in the West: A NEFA Backgrounder on Anwar al Awlaki" (PDF). The NEFA Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ Rayner Gordon (December 27, 2008). "Muslim groups 'linked to September 11 hijackers spark fury over conference'". Telegraph (UK). London. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Allen, Charles E. (October 28, 2008). "Keynote Address at GEOINT Conference". Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ Al-Awlaki, Anwar (December 27, 2008). "Anwar al-Awlaki:'Lies of the Telegraph'" (PDF). The NEFA Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Eckert, Toby, and Stern, Marcus, "9/11 investigators baffled FBI cleared 3 ex-San Diegans", The San Diego Union, September 11, 2003, November 30, 2009[dead link]

- ^ Imam Anwar Al Awlaki – A Leader in Need Archived 2007-04-02 at the Wayback Machine; Cageprisoners.com, November 8, 2006, accessed June 7, 2007

- ^ Sherwell, Philip, and Spillius, Alex, "Fort Hood shooting: Texas army killer linked to September 11 terrorists; Major Nidal Malik Hasan worshiped at a mosque led by a radical imam said to be a "spiritual adviser" to three of the hijackers who attacked America on Sept 11, 2001," Daily Telegraph, November 7, 2009, accessed November 12, 2009

- ^ Thornton, Kelly (July 25, 2003). "Chance to Foil 9/11 Plot Lost Here, Report Finds". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- ^ Al-Haj, Ahmed; Abu-Nasr, Donna (November 11, 2009). "U.S. imam wanted in Yemen over al Qaeda suspicions". Associated Press. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ Sperry, Paul E. (2005). "Infiltration: how Muslim spies and subversives have penetrated Washington". Thomas Nelson Inc. ISBN 9781418508425. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ "Anwar Al-Awlaki's Links to the September 11 Hijackers". The Atlantic. The Atlantic. November 11, 2009. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ JAGER Al-Haj, JORDY (August 16, 2011). "Rep. Peter King investigating links between Anwar al-Awlaki, 9/11 hijackers". The Hill. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Dao, James (January 21, 2010). "Man Claims Terror Ties in Little Rock Shooting". The New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ^ Mike Phelan; Mike Mount & Terry Frieden (June 1, 2009). "Suspect arrested in Arkansas recruiting center shooting". CNN. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ Dao, James (February 16, 2010). "A Muslim Son, a Murder Trial and Many Questions". The New York Times. Arkansas;Yemen. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ Kristina Goetz (November 13, 2010). "Muslim who shot soldier in Arkansas says he wanted to cause more death". The Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Hess, Pamela; Anne Gearan (November 21, 2009). "Levin: More e-mails from Ft. Hood suspect possible". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Brachman, Jarret (November 10, 2009). "Expert Discusses Ties Between Hasan, Radical Imam" (Interview: Host Michelle Norris). All Things Considered. NPR. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Coker, Margaret (January 15, 2010). "Yemen in Talks for Surrender of Cleric; Government Negotiates With Tribe Sheltering U.S.-Born Imam". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Ross, Brian; Rhonda Schwartz (November 19, 2009). "Major Hasan's E-Mail: 'I Can't Wait to Join You' in Afterlife". The Blotter from Brian Ross. ABC News. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ Associated Press staff (November 10, 2009). "FBI reassessing past look at Fort Hood suspect". The Monitor (McAllen, TX). Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ CBS/AP staff (November 11, 2009). "Hasan's Ties Spark Government Blame Game". CBS News. Associated Press. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Egerton, Brooks (November 29, 2009). "Imam's e-mails to Fort Hood suspect Hasan tame compared to online rhetoric". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ a b ADL staff (May 7, 2010). "Profile: Anwar al-Awlaki,Introduction". Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Hsu, Spencer S. (November 18, 2009). "Hasan Epitomizes U.S. 'Self-Radicalizing'; Accused Fort Hood Gunman Had Ties to Radical Cleric But Imam's Rhetoric on Web Fell Short of Triggering Legal Action". Washington Post. Retrieved January 24, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Sacks, Ethan (November 11, 2009). "Who is Anwar al-Awlaki? Imam contacted by Fort Hood gunman Nidal Malik Hasan has long radical past". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Barnes, Julian E. (January 15, 2010). "Gates makes recommendations in Ft. Hood shooting case". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ NEFA Foundation staff (November 9, 2009). "Anwar al-Awlaki: 'Nidal Hassan Did the Right Thing'" (PDF). The NEFA Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ ADL staff (November 24, 2009). "Profile: Anwar al-Awlaki, Connection to Alleged Fort Hood Gunman". Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ a b c Raghavan, Sudarsan (November 16, 2009). "Cleric says he was confidant to Hasan: In Yemen, al-Aulaqi tells of e-mail exchanges, says he did not instigate rampage". Washington Post. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Associated Press staff (November 16, 2009). "Imam Al Awlaki Says He Did Not Pressure Accused Fort Hood Gunman Nidal Hasan". The Huffington Post. Washington. Associated Press. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Esposito, Richard; Cole, Matthew; Ross, Brian (November 9, 2009). "Officials: U.S. Army Told of Hasan's Contacts with al Qaeda; Army Major in Fort Hood Massacre Used 'Electronic Means' to Connect with Terrorists". The Blotter from Brian Ross. ABC News. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Fox News staff (March 18, 2010). "Raw Data: 'Partial Transcript of Radical Cleric's Tape'". Fox News. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ Meyer, Josh; Nicholas, Peter (December 29, 2009). "Obama calls jet incident a 'serious reminder'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ a b "U.S. v. Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, Criminal Complaint" (PDF). Retrieved December 26, 2009 – via Huffington Post.

- ^ "Indictment in U.S. v. Abdulmutallab" (PDF). January 6, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2010 – via CBS News.

- ^ "'Underwear bomber' Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab handed life sentence". The Guardian. Associated Press. February 16, 2012 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Paula Newton (March 17, 2010). "Purported al-Awlaki message calls for jihad against U.S." CNN. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ Shane, Scott (March 13, 2010). "Arrest Stokes Concerns About Radicalized Muslims". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Ryan, Jason; Thomas Pierre (March 12, 2010). "N.J. Terror Suspect Sharif Mobley Tied to Radical Yemeni Cleric Anwar al-Awlaki; Sources Tie Nuke Plant Worker to Yemeni Cleric Called 'a Fixture of Jihad 101". ABC News. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Loeffler, Karen L. "Alaska man pleads guilty to making false statements in domestic terrorism investigation" (PDF). Press release. United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "Alaska man pleads guilty to terror-related charge". CNN. July 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Mary Pemberton (July 21, 2010). "Alaska pair pleads guilty to lying about hit list". Associated Press. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ a b Gregg MacDonald. "Fairfax County man accused of link to terrorist group". Fairfax Times. Archived from the original on July 30, 2010. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Joshua Rhett Miller (April 23, 2010). "Road to Radicalism: The Man Behind the 'South Park' Threats". Fox News. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Dreazen, Yochi J.; Perez, Evan (May 6, 2010). "Suspect Cites Radical Imam's Writings". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Herridge, Catherine (May 6, 2010). "Times Square Bomb Suspect a 'Fan' of Prominent Radical Cleric, Sources Say". FoxNews.com. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Fox News staff (May 1, 2010). "Times Square Suspect Contacted Radical Cleric". MyFoxDetroit.com. NewsCore. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Esposito, Richard; Vlasto, Chris; Cuomo, Chris (May 6, 2010). "Faisal Shahzad Had Contact With Anwar Awlaki, Taliban, and Mumbai Massacre Mastermind, Officials Say". The Blotter from Brian Ross. ABC News. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ Stephen Timms attacker was inspired by al-Qaeda's Anwar al-Awlaki, Telegraph, 02 Nov 2010

- ^ Shane, Scott (2010-06-03). "National Briefing – Southwest – Texas – Man Accused of Aiding Al Qaeda". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ^ a b Perez, Evan (June 3, 2010). "U.S. Terror Suspect Arrested - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ a b Shane, Scott (June 3, 2010). "National Briefing – Southwest – Texas – Man Accused of Aiding Al Qaeda". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ "Feds: Texas man indicted for attempting to provide support to al-Qaeda". CNN. June 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Rashbaum, William (June 6, 2010). "2 New Jersey Men Arrested on Terrorism Charges". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ "Two New Jersey Men Arrested on Terrorism Charges". The Wall Street Journal. June 6, 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Two New Jersey Men Plead Guilty To Conspiring To Kill Overseas For Designated Foreign Terrorist Organization Al Shabaab". United States District Attorney's Office – District of New Jersey. 3 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-07-13. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "Mohammad Youssef Abdulazeez Downloaded Recordings From Radical Cleric, Officials Say". NBC News. 21 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.