Peniscola

Peniscola

Peñíscola | |

|---|---|

| Peñíscola/Peníscola | |

Peniscola from the beach | |

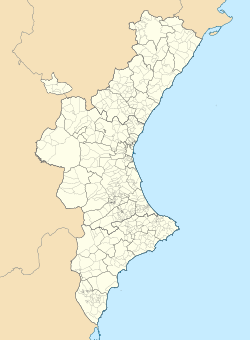

Location of Peniscola | |

| Coordinates: 40°21′33″N 0°24′27″E / 40.35917°N 0.40750°E | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous community | Valencian Community |

| Province | Castellón |

| Comarca | Baix Maestrat |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Andrés Martínez Castellà (PP) |

| Area | |

• Total | 79 km2 (31 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 46 m (151 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 7,447 |

| • Density | 94/km2 (240/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Peñíscolano, peñíscolana Peniscolà, peniscolana |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Official language(s) | Spanish, Valencian |

| Website | Official website |

Peñíscola (Spanish: [peˈɲiskola]) or Peníscola (Valencian: [peˈniskola]) and officially Peñíscola/Peníscola,[2] anglicised as Peniscola, is a municipality in the Province of Castellón, Valencian Community, Spain. The town is located on the Costa del Azahar, north of the Serra d'Irta along the Mediterranean coast. It is a popular tourist destination.

History

[edit]Peniscola, often called the "Gibraltar of Valencia", and locally as "The City in the Sea",[3] is a fortified seaport, with a lighthouse, built on a rocky headland about 220 feet (67 m) high, and joined to the mainland by only a narrow strip of land (tombolo). Peníscola is a local evolution of Latin peninsula. The history of the place goes back to the Iberians. Later the town became Phoenician, named Tyreche, then Greek, under the name Chersonesos (meaning "peninsula"). It was next captured by the Carthaginians under Hamilcar Barca; legend has it that this is the place where he made his son Hannibal swear an oath that he would never be a friend of Rome.[4]

The present castle was built by the Knights Templar between 1294 and 1307.[5] In the fourteenth century it was garrisoned by the Knights of Montesa, and in 1420 it reverted to the Crown of Aragon. From 1415 to 1423 it was the home of the schismatic Avignon pope Benedict XIII (Pedro de Luna), whose name is commemorated in the Castell del Papa Luna, the name of the medieval castle, and Bufador del Papa Luna, a curious cavern with a landward entrance through which the seawater escapes in clouds of spray.

The castle

[edit]The castle was originally built in 1307 by the Knights Templar and then in 1319 it was taken over by the Order of Montesa, they then ceded the castle to the Supreme Pontiff.[6] The castle was also where the Antipope Benedict XIII lived from 1417 until his death in 1423.[7] In 1960 the castle was restored using a pastiche[8] along with addition of new walls which were added for Anthony Mann's film El Cid which was partially filmed there. The town and castle of Peníscola played the role of Valencia. The castle is now a popular tourist attraction and the beaches and surrounding area are a popular family holiday resort.

Music festivals

[edit]Each summer, Peniscola hosts two music festivals: the International Festival of Ancient and Baroque Music (since 1996) and the International Jazz Festival of Peniscola (since 2004).[9][10] At the beginning of August, a pyromusical show opens the International Festival of Ancient and Baroque Music.[11]

Film festival

[edit]Peniscola hosted an annual comedy film festival that draws Spanish and foreign actors and filmmakers, and features screenings in historic venues. That the festival celebrates comedy is a natural fit; the city was the backdrop for Luis García Berlanga's comedic masterpiece Calabuch.

References

[edit]- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ "BOE-A-2008-13528 Decreto 90/2008, de 27 de junio, del Consell, por el que se aprueba el cambio de denominación del municipio de Peñíscola por la forma bilingüe Peníscola/Peñíscola".

- ^ "Peniscola Spain - Map - Weather - Information". Archived from the original on 2014-06-06. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ Hilowitz, Beverley (1974). A Horizon guide: great historic places of Europe. American Heritage Pub. Co. p. 119. ISBN 0-07-028915-8.

- ^ "The Commanderie of Peñiscola". Domus Templi. Lleida.org. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ^ Esaín, Guillermo (15 March 2024). "12 castillos españoles que dialogan con el mar: de Salobreña a Monterreal con parada en Peñíscola". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Compains, Nemesio Mercapide (1974). Crónica de Guarnizo y su Real Astillero: desde sus orígenes hasta el año 1800 (in Spanish). Institución Cultural de Cantabria, Centro de Estudios Montañeses, Diputación Provincial de Santander. p. 69. ISBN 978-84-600-6387-2. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Torrella, Josep (1965). Crónica Y Análisis Del Cine Amateur Español (in Spanish). Ediciones Rialp. p. 221. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ El Pais, 07/03/2021, ‘Festivales mini’, la resistencia musical de la Comunidad Valenciana

- ^ Cultura CV, 08/02/2020, Festival de Música Antigua y Barroca de Peñíscola 2020

- ^ El Mundo, 08/02/2019, La Pirotécnica Peñarroja iluminará el piromusical de Peñíscola

External links

[edit]This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Peñiscola". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 98.